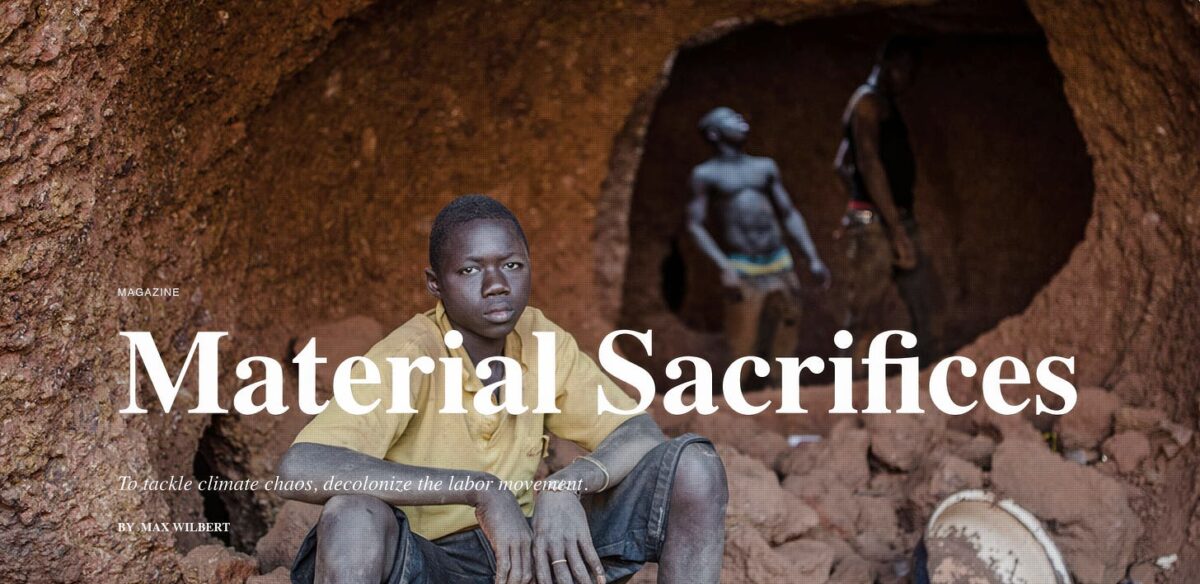

Green Jobs or Greenwashing?

by Max Wilbert | Oct 4, 2024

In January 2021, I traveled to an obscure part of northern Nevada with my friend Will Falk, pitched a tent, and began a protest campaign against a planned open-pit lithium mine.

Thacker Pass — known as Peehee Mu’huh in Paiute — would be our home for the next three years as we rallied opposition, filed lawsuits, allied with Tribal nations and ranchers, appealed to politicians and the White House, brought thousands of people to visit the land, and even took nonviolent direct action by standing in front of the bulldozers.

It wasn’t enough. Today, the landscape of Thacker Pass is being turned into an industrialized mining district, and the wildlife are gone. Backhoes and dump trucks have replaced sage grouse and pronghorn. The roar of diesel engines has replaced the howl of coyotes. What’s happening to the land is mirrored in the repression of land defenders. Seven of us are being sued for blocking construction, and two of us also face a $49,890.13 fine for building a latrine at the request of indigenous elders visiting the site to pray. If any of us return — even my Native friends for whom the land is a sacred burial ground — we’ll be arrested.

There are two great ironies here.

The first is that, because Thacker Pass is a lithium mine, and lithium is used in electric car batteries, the mining company, government, and big environmental groups all insist that despite the destruction it’s causing, the mine is “green.”

The second is that the workers who are building the mine belong to a union: North America’s Building Trades Union. The lithium which they plan to extract will be shipped to General Motors factories across the United States, where more union laborers (these from the United Auto Workers) will use it to assemble electric car batteries.

This is all an example of how today’s climate movement is attempting to bypass the “jobs versus the environment” debate that has raged for decades. The answer to this conundrum, they say, is green technology: solar panels, wind turbines, electric cars, and the mines, refineries, and factories to build them. According to the International Energy Agency, “If the world gets on track for net zero emissions by 2050, then the cumulative market opportunity for manufacturers of wind turbines, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, electrolysers and fuel cells amounts to USD $27 trillion. These five elements alone in 2050 would be larger than today’s oil industry.”

This translates directly into jobs, as politicians and organized labor have recognized. Joe Biden’s website proudly states “When I think about climate change, I think jobs.” The World Economic Forum expects there to be 24 million “green jobs” in the US — 14 percent of the national total — by 2030. And unions increasingly see this as opportunity to not only address global warming, but also for a re-industrialization that could revitalize the middle class.

But this revitalization comes not only at a cost to sacrifice zones like Thacker Pass, but also to people: More than two-thirds of the minerals used in renewable energy and electric vehicles come from mines on Indigenous or peasant lands, often in the Global South.

I grew up in a union family. My mom is a member of SEIU 1199NW, and I remember listening to her stories from the picket lines. Each summer, we’d go to see the great labor musician and storyteller Utah Phillips sing “The union makes us strong.” But I’m also an environmentalist, and this leaves me in an uneasy position when workers looking for good jobs end up working in industries that are destructive to ecosystems and communities and that depend on cheap labor abroad.

Behind each piece of green technology is extraction. A recent International Energy Agency report estimates that reaching “net zero” by 2050 would require six times the amount of minerals used today. Another researcher found the energy transition would require mining as much metal over 15 years as was extracted between the dawn of humanity and 2013.

“Mining is unavoidably destructive to the environment and human rights,” says Jamie Kneen, co-founder of MiningWatch Canada and one of the world’s leading watchdogs of the industry. Only some of these impacts can be abated, he says. And even then, “avoiding or mitigating harm costs money — and mining companies are amazingly reluctant to spend it.”

According to a community activist group in the Philippines I spoke with, the problems with mining go much deeper than the lack of funds and will for harm reduction that Jamie Kneen mentioned. The group calls themselves the Local Autonomous Network (LAN), and their representative has asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons. (According to Global Witness, at least 281 land defenders were killed in the Philippines between 2012 and 2022. Those responsible, my contact tells me, are vigilantes, private security personnel working for mining and logging companies, and the military.)

“Mining is part of a system of neocolonialism or domination,” the LAN representative told me. “The United States occupied the Philippines from 1898 until 1946, and America never left.” The legacy of that occupation, they add, includes a “framework of development which is very destructive to our environment and culture.”

Chief among these imposed systems, they say, are exploitative free trade agreements and structural adjustment programs which bankroll extractive industries like mining. The Philippines is one of the world’s leading sources of minerals, especially nickel and copper, and the comprador government (along with multinational corporate partners and institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund) is promoting the construction of more mines.

This, the LAN representative says, is leading to “environmental destruction, displacement, abduction, and killings.”

A member of the Local Autonomous Network looks out across southern Luzon, the largest island of the Philippine archipelago. In this area, farms and industrial projects increasingly encroach into forests, a large Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) terminal has been built, and communist rebels have engaged in firefights with the army. Photo by the author.

Stories like these are unfortunately the norm in global mineral supply chains. In Guatemala, Russia, Argentina, Indonesia, and scores of other nations around the world, mining corporations have been implicated in land theft, violence, assassinations, sexual abuse, and pollution. Many elements in renewable technology supply chains, including nickel, copper, iron ore, and cobalt, involve well-known human rights violations and environmental destruction. This has led Sami indigenous activists in Northern Sweden to begin calling these new extraction projects “green colonialism,” and the term has caught on.

And as always, dirty and polluting industries always disproportionately harm the poor. “The depositing of toxic wastes within the black community is no less than attempted genocide,” proclaimed Dr. Charles E. Cobb at a 1982 protest deemed the beginning of the environmental justice movement. Cobb wasn’t exaggerating, as history has shown that dirty businesses often deliberately target communities with little political or economic power. For example, in 1991 Lawrence Summers, then Chief Economist for the World Bank, penned a now infamous leaked memo stating that “countries in Africa are vastly underpolluted” and encouraging “more migration of the dirty industries” to the Global South.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which supplies most of the cobalt used in electric vehicles, smartphones, and other rechargeable batteries, the situation is dire. In his 2023 book Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives, global slavery researcher Siddharth Kara writes of the brutal working conditions, child labor, slavery, and environmental devastation in the DRC’s cobalt industry:

“The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains. Declarations by multinational corporations that the rights and dignity of every worker in their supply chains are protected and preserved seem more disingenuous than ever.

The translator for my interviews, Augustin, was distraught after several days of trying to find the words in English that captured the grief being described in Swahili. He would at times drop his head and sob before attempting to translate what was said. As we parted ways, Augustin had this to say, ‘Please tell the people in your country, a child in the Congo dies every day so that they can plug in their phones.’”

Besides environmental devastation, the inequalities at play in these industries are staggering. According to Kara, the average male miner in the Congo makes less than $500 a year, and the average woman makes much less. That’s less than half of 1% of the annual average salary in the U.S. mining industry, which is $85,000.

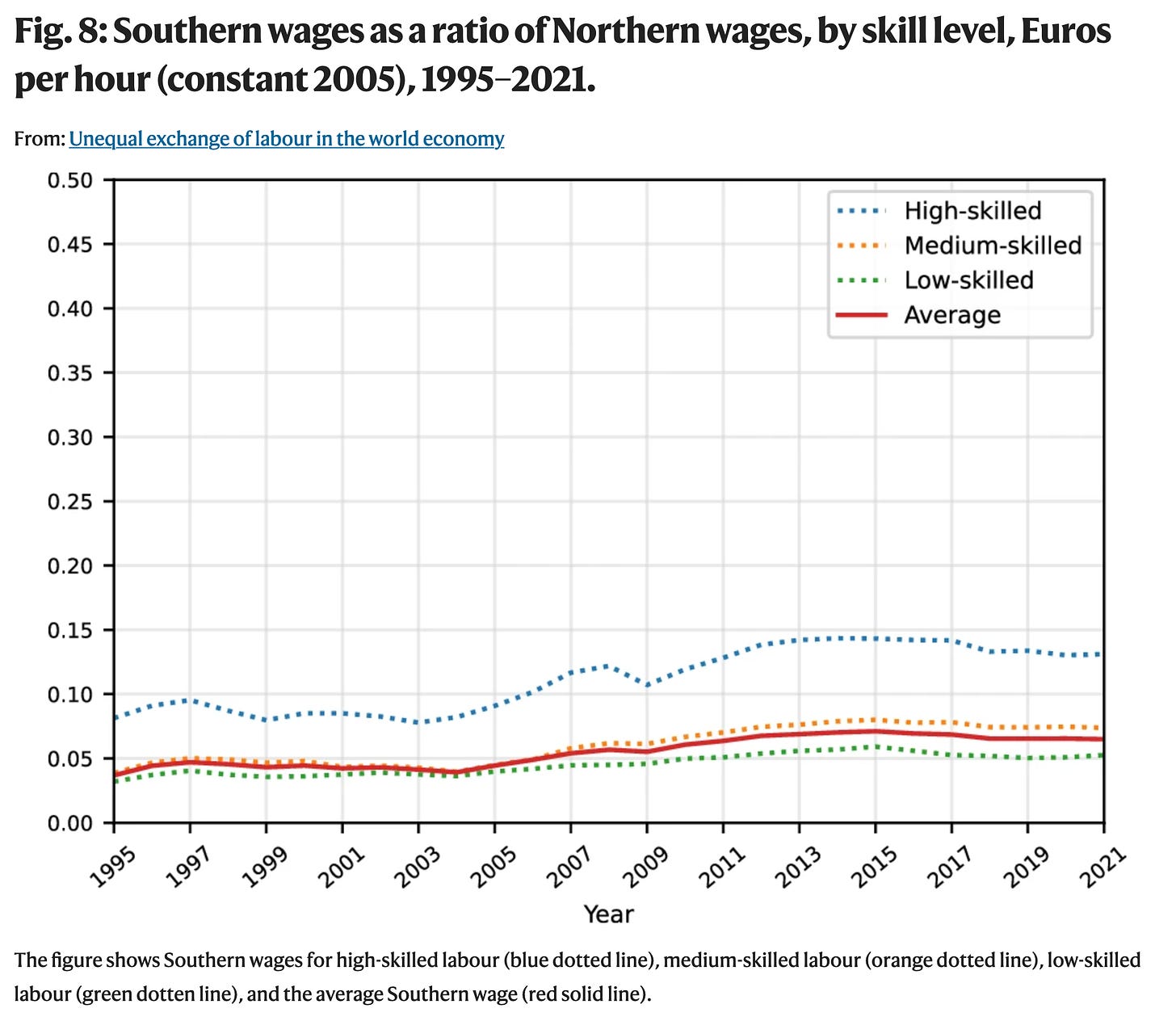

Meanwhile, new research published in the journal Nature Communications found that this is the norm. According to the paper, 99 percent of mining labor is in the Global South, and wages there are between 87 and 95 percent lower than what workers doing the same job are paid in the Global North. Lead researcher Jason Hickel says this is the “result of imperialist dynamics in the world economy” that funnel cheap resources from poor countries to rich ones. (The vast majority of metals mined in the Global South are exported to the Global North.)

An image from the paper “Unequal exchange of labour in the world economy.” It shows that on average, workers in the Global South are paid roughly 94% less than workers doing the same job in the Global North, across all sectors.

The question of how to change this injustice is challenging, because the imperialist dynamics Hickel refers to are profitable — and powerful individuals, corporations, and the governments they bribe will act to protect the sources of their wealth with laws, courts, police, militaries, and more.

That’s certainly the case at car companies using lithium from places like Thacker Pass and cobalt from the DRC. I spoke to one employee of a major US automaker who told me that, after she spoke to her co-workers about human rights and environmental issues in her company’s supply chain, she “hit a legal wall.” The message from her managers amounted to stop asking questions and don’t make trouble, and she backed down. “I have to have a job,” she told me.

The scale of systemic barriers is sometimes stunning. In Panama, mass protest movements led the government to ban all new mines in 2023. But earlier this year, a corporate investor filed a lawsuit claiming the ban violates the Panama-Canada free trade agreement by infringing on a foreign corporation’s right to mine. If the investor wins, the Panamanian government may be forced to pay billions in restitution. In a similar case in 2019, arbitrators at the World Bank ordered Pakistan to pay an Australian mining company $11 billion after the country refused to permit a copper/gold mine. Facing a fine equivalent to a quarter of its entire government budget, Pakistan was forced to back down and issue the permits. Meanwhile, nearly 40% of children in Pakistan are stunted due to hunger.

“We see this as systematic violence,” the LAN representative tells me. “The West can never have an ethical relationship with the Global South if all they want is our resources. But there is no one type of action that will solve this. Boycotts, strikes, education, that is all great. But we need to act more deeply and collectively.”

Denzel Caldwell, a community organizer and economist with the Tennessee-based Highlander Center, a century-old school for social justice and labor organizers whose alumni include Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and Rosa Parks, agrees with the need for radical, even revolutionary action. “We need to reshape the relationship between the Global South and the Global North entirely,” Caldwell says. “This is why labor forces need to adopt a decolonial lens. We all want better working conditions, but does solidarity end at the US border?”

The need to reshape the relationship between the Global North and Global South has been discussed among community organizers for decades. The late civil rights activists Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs wrote in 1974 that “the revolution to be made in the United States will be the first revolution in history to require the masses to make material sacrifices rather than to acquire more things” — possessions which, they write, “this country has acquired at the expense of [the Global South].”

In the Boggs’ view, moving away from consumerism requires “re-imagining ourselves… beyond capitalist categories.” In other words, rather than just imagining fairer wealth distribution and “greener” products like electric cars, they envisioned a society working towards non-monetary goals.

Other activists have sought to bring together labor and environmental movements for radical economic and social transformation. In the early 1990’s, Judi Bari — an activist who helped spearhead Earth First! campaigns to protect redwood forests in Northern California — began working in collaboration with loggers to both end cutting of old-growth and advocate for workers rights.

In her 1995 essay “Revolutionary Ecology,” Bari wrote:

“With the exception of the toxics movement and the native land rights movement most U.S. environmentalists are white and privileged. This group is too invested in the system to pose it much of a threat. A revolutionary ideology in the hands of privileged people can indeed bring about some disruption and change in the system. But a revolutionary ideology in the hands of working people can bring that system to a halt.”

It is, perhaps, a testament to the potential in Bari’s theory that she and Darryl Cherney were bombed in 1990 in Oakland in a still-unsolved crime that many blame on the FBI.

Meanwhile, alternatives to capitalist modernity are increasingly common around the world. In Bhutan, the constitution adopted in 2008 directs the government to minimize income inequality, protect the environment, and prioritize “Gross National Happiness” rather than Gross National Product (GDP). In Europe, the degrowth movement is calling for a planned democratic contraction in the use of energy and raw materials, sacrificing economic growth for justice and sustainability while trying to maintain good standards of living. And in South America, a concept called “Buen Vevir,” which is rooted in Indigenous traditions and prioritizes harmony between humans and nature, is gaining ground.

While none of these alternatives are perfect, Caldwell says they are crucial. His work focuses on the solidarity economy, which he describes as “an umbrella term for institutions and practices that are grounded in mutualism, cooperation, democracy, pluralism and building a world beyond racial capitalism.”

As examples, he lists worker-owned cooperatives; time banks — a bartering system where people exchange services for hourly time credits, rather than money; participatory budgeting — a democratic process in which community members decide how public funds are spent; and community land trusts that function as responsible stewards of the land use on behalf of place-based communities.

But none of these, he says, are “possible to scale up under global capitalism.”

Under a full moon, mine opponents gather around the campfire at the Protect Thacker Pass land defense camp on a frigid winter night in February 2021. Photo by the author.

The fate of the land, indigenous communities, miners, and workers have always been bound together. Back in 2021, as we sat around the campfire at Thacker Pass, Paiute elders told us stories about U.S. Army soldiers massacring their ancestors at a campsite nearby. These stories soon led us us to discover written accounts of the 1865 massacre. The first came from the autobiography of a legendary labor organizer named William “Big Bill” Haywood, who worked a mine a scant few miles from Thacker Pass for several years starting in 1884. In his book, Haywood recounts conversations with both Ox Sam, a Paiute survivor, and Jim Sackett, a U.S. Army soldier who had participated in the attack. Haywood writes that Sackett’s “tale seemed to pull a lot of the [glory away from]… the alluring Indian fighters I had read about.” The popular stories of brave Army troops he had heard didn’t square with “killing women and little children while they were asleep.”

That compassion was a constant throughout Haywood’s life. A decade after his time at Thacker Pass, he would co-found the Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, a revolutionary union built on principles of solidarity. It was the first in the country to welcome all workers — African and Asian Americans, women, and immigrants. Their motto was “An injury to one is an injury to all,” a slogan still widely used across the labor movement.

Today, many labor organizers who have already been grappling with the climate crisis are now recognizing the contradictions in the energy transition.

“This new ‘green’ industrial growth is going to create massive environmental chaos and displace millions of Indigenous people,” says Chandan Kumar, national coordinator for an Indian coalition of labor groups called The Working People’s Charter. “But we don’t have an alternative framework yet. [Here] we are still stuck on basic questions like minimum wage. We have workers here in the Volkswagen, General Motors, and Mercedes supply chains making clutches or gears, and their salary is $100 a month. They don’t have enough food to eat.”

Kumar thinks that real change will require a type of global labor and nature solidarity we haven’t seen yet , but he sees positive signs. Under the leadership of Shawn Fain, for example, the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) — one of the largest and most diverse unions in North America — has recently been willing to take on political minefields like calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. Kumar hopes this means labor organizers may soon be willing to go further on other issues, too. “They [unions in the Global North] need to be more proactive,” he says.

Caldwell agrees. “Labor radicalism is a long tradition that’s been buried,” he says. “A hundred years ago, workers weren’t afraid to combat the state and there was a stronger sense of internationalism. We need to remember that history. It’s important for people not only to change their working conditions, but also fundamentally question the industry itself.”

Kumar finds the tension between the harms of so-called ‘green’ industries and workers rights challenging. “I’m lost and confused,” he tells me. “We’re in a sandwich-like situation here.”

0 Comments