Agreement, Mutual Aid, and Love (Reviving Federalism, Part 2)

by W.D James | Oct 16, 2024

Three of the most important factors in the emergence, growth, and maintenance of organic social order are free agreement, mutual aid, and love. Typically, a particular thinker will emphasize one above the others. In his foundational political treatise on federalism of 1603, Politica, Johannes Althusius brings them all into play and weaves them together in intricate and harmonious ways. I’m becoming increasingly convinced that he is a great modern thinker and it is a tragedy that he fell into relative obscurity. We need to recover a deeper understanding of federalism as a model of social organization and that means we need to recover Althusius.

In this essay, we will focus in on the opening chapter of that work dealing with “The General Elements of Politics.”

Politics

Althusius opens: “Politics is the art of associating men for the purpose of establishing, cultivating, and conserving social life among them.”i He is explicitly following Aristotle in understanding politics as a matter of association. In fact, Aristotle provides much of his framework. Politics arises when people “pledge themselves each to the other, by explicit or tacit agreement, to mutual communication…”.ii The translator makes clear that Althusius’ ‘communication’ is rooted in Aristotle’s ‘koinonia’, so it should be understood as emphasizing sharing; communing. The first two levels of society will be the family and what Althusius calls the ‘collegium’ by which he means a guild, corporation, or other organization established to serve the interests of its members and of the society as a whole.

He also follows Aristotle in utilizing a four-fold conception of causation: efficient, material, formal and final. The final cause, or end, to which politics is directed is understood to be “holy, just, comfortable, and happy symbiosis [living together], a life lacking nothing either necessary or useful.”iii The efficient cause is the voluntary agreement that establishes the association. In the case of the family, the agreement between the man and woman forming the family. In the case of a collegium, the agreement of the membership.

People are naturally inclined to enter into these voluntary associations because “no man is self-sufficient.” Althusius, now bringing in the other major component of his intellectual framework, Christianity, interprets this as an aspect of God’s Providence. “God distributed the gifts unevenly among men,” he observes, “He did not give all things to one person, but some to one and some to others, so that you have need for my gifts, and I for yours.”iv Hence, it is by “mutual aid,” as he terms it, that we commune with one another in the “commonwealth” we form.

He refers to the members as “co-workers” and “partners in a common life.”v This common enterprise will encompass “communication” of things, services, and “common rights.” In short, we will associatively provide things for one another, do services for one another, and this will all be organized under a shared sense of justice we develop amongst ourselves. This sense of justice, embodied in laws, will “distribute and assign advantages and responsibilities among the symbiotes according to the nature and necessities of each association.”vi The notion that there would not be a ‘one size fits all’ approach to different people, and more specifically different groups, will probably sound very foreign to our modern liberal ears, but it is characteristic of all organically developed societies. Further, these rights will always be balanced with responsibilities. Society as a whole will support you as an individual or group to thrive (rights) but then you have obligations to operate in a way that contributes to the overall good (responsibilities).

To take this back to the more literal organic level, we might prune some plants in our garden and not others, we might supply different sorts of fertilizer to different plants, we will pick the fruits at different times and use them for different purposes. The parts of our garden are different and need different things for the garden as a whole to thrive. In turn, having received what they each need, each plant will yield us a unique good. Likewise, in an organic society, different parts do different things and need different things to thrive for the overall good of the whole.

The economic historian R. H. Tawney drew out the significance of this conception by contrasting ‘the Functional Society’ to ‘the Acquisitive Society.’ The latter is the sort of society that has grown up in Western Europe in the modern era characterized by the assumption that the foundation of society lies in “rights” divorced from obligations or overall social function; ie, capitalism. “Such societies,” he argues, “may be termed Acquisitive Societies, because their whole tendency and interest and preoccupation is to promote the acquisition of wealth.”vii He argues for a recovery of “purposes” and hence social “functions” in our understanding of industry and production. The essential question is: does society exist to serve the economy or does the economy exist to serve society? If the latter, we must start asking how? To what end? What functions does it perform for us?

Also following Aristotle, Althusius takes that each association in the network of associations would have a leader or governor. How these leaders are to be chosen, the strict limits on their authority, and how you would remove them when they become tyrannical will be examined in future essays. Essentially, he assumes that any organism will have a governing element. In the individual the ‘soul’ governs the whole body, the head governs the rest of the body. Each social body (each family, each collegium, each city, each province, each nation) needs a head charged with executing the will of that body towards its natural social end.

In structuring these relationships of authority he introduces the third great associative principle, also borrowed from Christianity, love. Following St. Augustine, Althusius holds that to “govern… is nothing other than to serve and care for the utility of others, as parents rule their children…”.viii The principle is elaborated as follows: “…just as the soul [or mind] presides over the other members in the human body, directs and governs them according to the proper functions assigned to each member, and foresees and procures whatever useful and necessary things are due each member…,” so the role of leadership is to understand what the members of the association need and to coordinate this to serve the common good. This is nothing other than the classic Christian conception of love (agape) as serving the good of the other.

We will need to look at his theory of resistance to tyranny in detail later, but from this opening section of his work, we will note that resistance becomes justified when the “chief” of an association governs “impiously or unjustly.”ix

Agreement

It is good that Althusius uses the broader term ‘agreement’ rather the more narrow ‘contract.’ Agreement denotes a more genuinely cooperative endeavor. Contract implies cooperation only so far as that remains within my individual self-interest.

This is probably the most general way in which voluntary associations are formed. A family forms when two people agree to be married. Guilds, clubs, business partnerships, institutes, etc form when people agree to work together to form them. Pretty much by definition this preserves individual liberty within cooperative endeavor. No one is forced to be a member of anything they don’t want to be. The main exemption would be children not having agreed to enter the families they happen to enter. Too bad, the not yet existent don’t get to choose anything until they start to exist (they can always abandon their families later if they choose).

Mutual aid

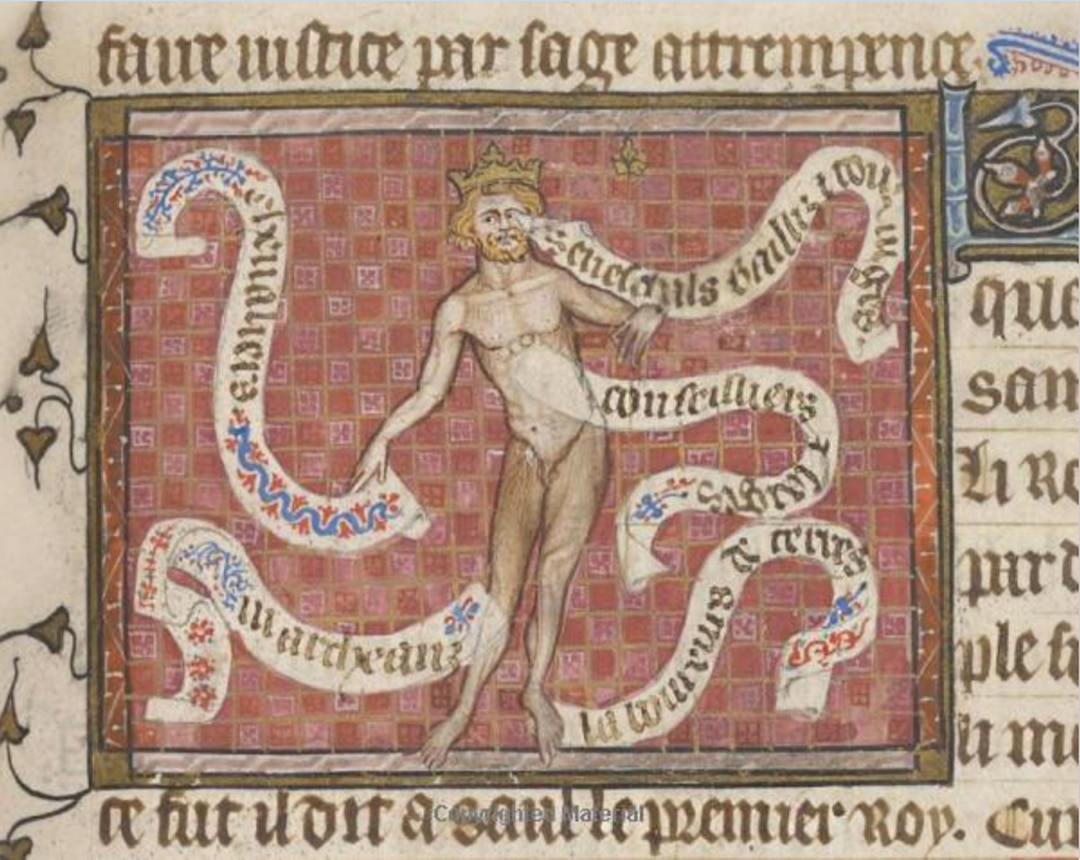

Althusius interprets mutual aid, following Aristotle, mainly in terms of the shared ends we will pursue. Three centuries later, Peter Kropotkin (pictured) would make mutual aid the centerpiece of his political and ethical theory. He approached it though from an evolutionary perspective, hence what Aristotle would have considered as an element in efficient causation. His main contribution was to highlight how much the cooperative factor of mutual aid played in the ‘struggle of the fittest’ Darwin had elaborated upon. In his Ethics (1921), he asserts “Mutual aid within the species thus represents the principal factor, the principal active agency in what we may call evolution.”x His essential point being that, among social species, the essential thing in determining success against other species or against the harshness of the environment is the degree and effectiveness of the group acting cooperatively.

Further, for Kropotkin, this is the (efficient) cause of morality. He says: “Nature has thus to be recognized as the first ethical teacher of man. The social instinct, innate in men as well as in all the social animals, — this is the origin of all ethical conceptions and all the subsequent development of morality.”xi So, from this direction, morality is just formalization of concepts which are necessary to, and which support, human cooperative endeavor. Don’t lie. Don’t murder. Don’t cheat. Don’t covet. Don’t steal. These are bad because they would weaken mutual aid and, hence, decrease the chances of that community’s survival.

In a very real sense, we would not have the opportunity to act in a narrowly self-interested sense if we (and especially our forebears) did not usually and reliably act cooperatively. Cooperation is socially fundamental. Increasing mutual aid is the fuel that allows for social growth and development.

Love

I think love is quite possibly the most neglected concept of politics in the modern world. I think a degree of hierarchy and authority are natural and ineradicable from human societies. This is most inescapable in relation to children. Either parents (or some surrogate) will educate and guide children or the kids are likely to not make it to adulthood and will be ignorant and anti-social if they do. Often, the elderly will need to have decisions made for them when they become too ill or feeble to make decent decisions for themselves.

Even in other social relationships I think this is unavoidable, but abuse of authority will need guarded against. If we’re running a manufacturing operation, no matter how co-operative, we’re going to need some folks to make day-to-day decisions: we aren’t going to all gather together to vote on every minute detail. Hopefully those allotted this role will possess the necessary excellences to make good decisions and that’s why we would pick them for that role in the first place. If we form a military to protect ourselves from those mean enslavers across the river who would like to include us as their chattel, we won’t operate very well if everything is a voluntary group decision. We will need some leaders. Hopefully brave, smart, civic-minded ones.

At a personal level, I have been in the ‘authoritative’ role in regard to lots of students as their teacher, my daughter as her father, and lots of co-workers as their supervisor. It is profoundly odd that we would think one human had any sort of ‘right’ to tell another what to do. I think we are sort of conditioned to not notice how odd that actually is, probably because so much of our hierarchy and authority (really just power much of the time) is actually not legitimate.

We typically rely on contract to solve this problem: you agreed to be ruled, politically, at work, whatever, and so you are subordinate. The obvious problem is that such contracts are usually made under some degree of compulsion. The employee and the employer, for example, do not start from equal positions of power and, hence, the contract typically does not equally represent their interests.

The only thing that I think can fully legitimate a relationship of hierarchy is love. Immanuel Kant put this rather rationalistically as “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.” Jesus put it more succinctly as “Do to others what you would have them do to you.” Put in terms I’m most comfortable with, it comes down to: if you claim the right to tell someone else what to do, that can only be legitimated by taking on the responsibility of giving full weight to their good (ie, loving them). There are all sorts of situations in which some sort of hierarchy naturally arises. Parents need to nurture and direct children. The already educated will need to teach the not yet educated. It will be convenient to delegate a coordinating authority to someone or a group of someones: say in building bridges between syndicates to form a cartel, or between cities to coordinate exchange or mutual defense. Each of those sorts of things require tons of day-to-day decisions. It would be very inefficient to involve the whole group in each and every one of them. I see it as natural that such a group, no how democratic or decentralized, would find it convenient to delegate a well-defined authority to set capable people to execute the details in fulfillment of the group’s will. When a hierarchy is necessary or desirable, only by being exercised through love can it be legitimated.

Most folks, if they’re reasonable, will admit the legitimacy of hierarchy rooted in competence and exercised through love. That is not a tyranny. Lacking either element, I think it starts looking pretty questionable.

Subscribe to Philosopher’s Holler

i Johannes Althusius, Politica, edited and translated by Frederick S. Carney, Liberty Fund, 1995, p. 17.

ii Ibid, p. 17.

iii Ibid, p. 17.

iv Ibid, p. 23.

v Iibid, p. 19.

vi Ibid, p. 22.

vii R. H. Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, Writat, 2022 (1920), p. 20.

viii Op cit., p. 20.

ix Ibid., p. 21.

x Prince (Peter) Kropotkin, Ethics: Origin and Development, translated by Louis S Friedland and Joseph R. Piroshnikoff, Benjamin Blom, 1968, p. 45.

xi Ibid., p. 45.

0 Comments