American Exceptionalism Is on Deadly Display in Ukraine

Click to subscribe on: Apple / Spotify

Feb 11, 2022

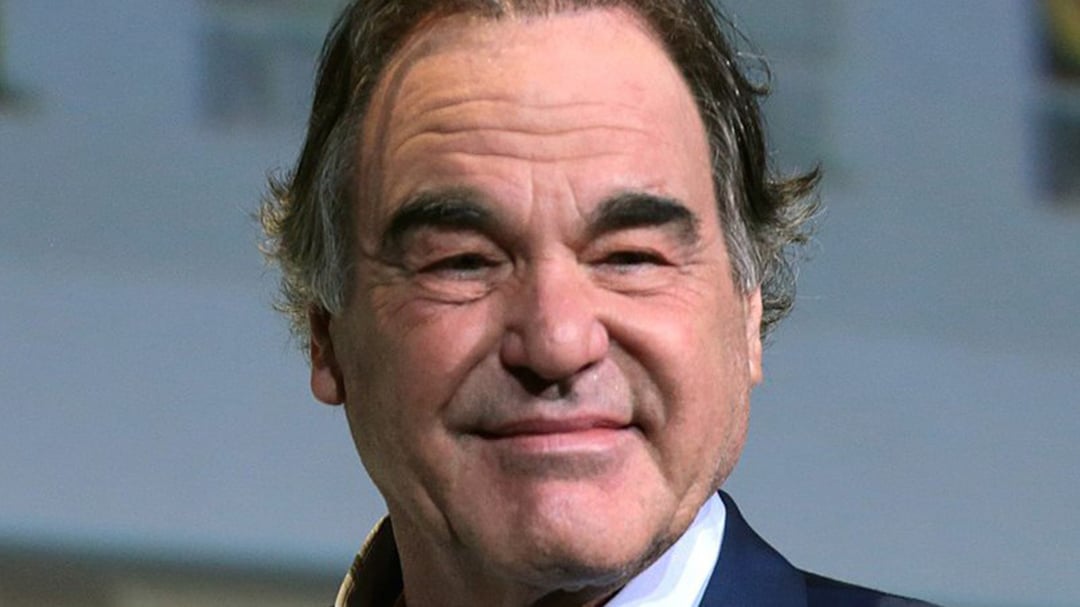

Oliver Stone, the creator of the Showtime documentary series “The Putin Diaries” speaks to Robert Scheer about the escalating crisis in Ukraine.

“The crisis over Ukraine grows simultaneously more dangerous and more absurd,” Katrina vanden Heuvel recently wrote in The Nation.

Rather than help de-escalate the growing conflict between Ukraine and Russia over the Donbas region, it seems like the Biden administration and U.S. corporate media have been beating the war drums. The result of any war, needless to say, would be catastrophic for all involved and would have pernicious repercussions the world over.

U.S. reports, according to “Scheer Intelligence” host Robert Scheer, have failed thus far to understand the perspective of Russia and its leader Vladimir Putin, and do so to the detriment of everything and everyone at stake. Film director Oliver Stone, however, offers a unique insight into the crisis given his experience interviewing the Russian leader a dozen times over two years for Stone’s Showtime series “The Putin Diaries.” The Oscar winner and Vietnam War veteran joins Scheer on this week’s show to discuss the critical nuances Americans are missing in Ukraine.

“No one really knows what’s going on in the actual sense of being in Russia’s mind,” Stone tells Scheer, “but I do think, from the beginning, this has been a defensive maneuver from the Russian side. The United States and its allies in NATO have been provoking Russia [and] have been using Ukraine as bait, as a temperature-taker of that region [since 2014]. Now we’ve reached this place where they have threatened the Russians so much that they had to react, because I don’t think Putin could have stayed in office if he had not reacted.”

Scheer argues that one of the most toxic elements at play in this international brinkmanship is nationalism, a force he warns against, especially in the form of American exceptionalism that views and pursues the country’s interests as “global interests.” Oliver and Scheer also examine a recent joint statement from Russia and China that they believe marks a paradigm shift in global politics. Listen to the full conversation between Oliver and Scheer as they thoughtfully discuss how U.S. nationalism requires crises like the one brewing in Ukraine to sustain its national narratives.

Credits

Host:

Producer:

RS: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, Oliver Stone. And I’m going to say, on the subject I want to talk about—Vladimir Putin, Russia, and what’s going on with the Ukraine, what’s going on with the world—I’m going to say it right here, I think Oliver Stone has a viewpoint about Putin, knows about Putin in a way, I don’t know if there’s anybody else I could be calling right now.

He did the Putin interviews for Showtime; I thought it was an incredible documentary. The New York Times, which, you know, got a very angry Russian émigré to attack it, Masha Gessen—but I have looked at this thing over and over, and I think it’s an incredible insight into another government leader that we have to do business with. And Oliver did a dozen interviews over a two-year period with Putin; I found it a candid look, and I just want to praise it as a work of journalism, which obviously the New York Times didn’t do.

But whether we like Putin or hate Putin, we’ve got to figure out what he’s doing now. And with the recent declaration between Xi, the Chinese leader, and this Russian leader, that they have a common view of the Western alliance being, really, basically another way of describing U.S. hegemony, using NATO to really push people around. And that they have now an agreement to withstand it, means you just can’t easily say you’re going to just cut people off economically and so forth. That represents a pretty powerful coalition.

So let me just begin with that. You know, what the hell is going on? You’re a guy who fought communism in Vietnam, you got the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, everything else. We would have thought this many years later we still wouldn’t be screwing around with some kind of Cold War scenario, but we are.

OS: Yeah. Well, Bob, I thank you for your comments, very nice of you. You actually are one of the few people in the United States who looked at the Putin interviews, and looked at it, as opposed to criticized it without seeing it, which is what often happened. So I’ve known you a long time, and I think you and I pretty much agree on the United States’ position in the world, and what’s going on.

So I’m going to take it from there, and just tell you what I think is going on right now. No one really knows what’s going on in the actual sense of being in Russia’s mind, but I do think, from the beginning, this has been a defensive maneuver from the Russian side. The United States and its allies in NATO have been provoking Russia for, since two years now—actually three years over the Ukraine; more. I mean, they started this in 2014.

But they have been using Ukraine as bait, as a temperature-taker of that region. And now we’ve reached this place where they have threatened the Russians so much that they had to react, because I don’t think Putin could have stayed in office if he had not reacted. So this is a game that’s somewhat like the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962; Russia is concerned, very tense; and the United States and its allies don’t seem to be listening to its concerns, don’t seem to care about its concerns about NATO, and specifically Ukraine.

But it’s not just Ukraine. It’s also the Baltic; it’s the constant war exercises in the Baltic region, it’s the pressure from Europe, it’s the United States—in the air, we send our bombers close to the border [unclear]. So we’re constantly provoking them, going into their territory. If we can think of it as Canada and the United States—if Canada were doing that, and sending warnings to us like this, we would be freaking out. I would think Canada is somewhat like—Ukraine is to the Russians like Canada is to the United States. In other words—yeah, go ahead.

RS: Well, let me just push this a little bit, because I say it in the intro. You actually talked to Putin. And, you know, this guy has been demonized. Because, you know, if you go back to Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, his great fear that he discussed was the need of the new empire—whatever it was, and America fits the bill now, with its 800 bases—to constantly have an enemy.

And the whole contradiction with Russia—at least with China, which we get along with a lot better than we do with Russia, because we need them. China took us through the pandemic; China made Jeff Bezos the richest man in the world because most of the goods that we’re consuming to get through are from China. So whether they’re communist or not communist, they’re very good capitalists, and we need China. And China has 1.4 billion people; Russia has 140 million people, it’s got a military, it’s got a big land mass.

But the big contradiction, whereas at least the Chinese still have a communist party in power, Vladimir Putin was picked by the United States; he was picked by Yeltsin, who was the guy that the United States liked more than Gorbachev. And Putin was brought into power, basically, because Yeltsin was a hopeless drunk, and Putin at least represented sobriety and some kind of conservative, Russian Orthodox nationalism. Clearly he had broken with any communist past.

So the inconvenience here is we are demonizing a guy who got elected by defeating the remnants of the old Russian communist system. And yet it doesn’t matter; logic doesn’t matter, facts don’t matter. We need an enemy. That’s the way I see it. And Putin is the enemy. So tell us about this enemy, because he’s clearly not a communist ideologue; he clearly doesn’t quote Marx extensively, and he’s actually a conservative, what, at best a Peter the Great, czar-type figure.

And you’ve met him; I mean, it’s no small thing. It’s very interesting to dismiss someone of your worldwide experience—you’ve interviewed a lot of people, you’ve seen war, you’ve seen the world; and yet somehow your two years of trying to figure out Putin, and your dozen interviews, which I think is a real important reservoir of information, gets ignored. And all these people in journalism and everywhere, they’re talking about Putin, Putin, Putin, as if he’s Stalin or something.

OS: I know. I know.

RS: It’s nutty! It’s nutty, is what it is.

OS: And it’s scary. Last week I was looking at the American news, and I could not believe how bloodthirsty the journalists were. CNN and Fox both were demanding, almost demanding our leaders to take on, to get tough with the Russians, because we have taken enough [unclear] from them. As if Putin had pushed all our buttons; as if he was the aggressive one. I saw young women with no experience [unclear] in their thirties, talking about the need to really go after Russia. And then they would cut to some general in civilian clothes, or some guy from a think tank who was going to tell them what they want to hear.

I didn’t see one person on television who was talking for peace, talking to understand Russia; I really didn’t. And it’s very, as you say, these people like Masha Gessen, who is to the right on most things Russia, are telling us what the Russian point of view is, but it’s just not true. The Russian point of view has always been consistent, and Mr. Putin has always been consistent in what he says. And he says, basically, the argument is, OK—well, first of all, I wouldn’t say that he got in to power because of us. I do think that Yeltsin, who was not as drunk and hopeless as you think—but I do think Yeltsin chose him. But the United States came down on Putin after his speech in Munich in 2007, when he said there has to be a line, and—

RS: Yeah, but that was seven years after he got elected with our blessing, and he defeated the communist party candidate. He was the anti-communist when he got elected.

OS: Absolutely, and he has no fondness for the old empire, as many of these Russia thinkers say. It’s nonsense; he has no desire to return to that; he is looking for security. Security is the mother word here. He’s a son of Russia. The Russian people demand security; they do not want to be all the time threatened by a Western power that is telling them you have to do this and you have to do that.

But NATO is also a huge threat, because we’ve seen NATO expand since 1989 by 13 countries. And now there’s talk of course with Ukraine joining NATO and all that stuff. But the truth is, NATO is seen by the Russian people as an enemy. They bombed Yugoslavia in the 1990s, if you remember; they attacked Libya. NATO has turned from a defensive organization into a very aggressive organization. They were in Iraq; we’ve seen their activities in Afghanistan. NATO continues to be an arm of the United States to bring offensive operations.

And this is—it’s not working, and what Putin is saying in general is: lay off; back away. You cannot run war exercises all the time on our borders; you cannot talk this language of calling us the aggressor. And that’s what’s very interesting to me, is the United States media always say—every day I see it in the newspaper or this or that—the Russian invasion, the coming Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Now, this is outrageous, because first of all, they have no proof that Russia intends to invade Ukraine; I doubt that they would. I think Russia is concerned only with the Donbass region. The Donbass region being the eastern sector where the Russian-speaking people are threatened by the Ukrainian government. Why? Because, we saw back in 2014, they were killing them. There was quite a bit of murder going on, and the Ukrainian government did not want to recognize the historic autonomy of the eastern Ukraine, of the people who speak Russian. In fact, Russian language was banned in Ukraine, if you remember correctly.

And there’s been a general strong, almost nationalistic attack on Russia from those years. And we know about the old Nazis, the Nazis from World War II, their inheritors are in Ukraine; there’s quite a few fascist people there who are working and putting pressure on the government to attack Donbass. You saw what happened, if you remember correctly, in Odessa, when the Russian-speaking natives were surrounded in a building and the Ukrainian nationalists burned them alive. That was a horrible moment, and what was it, 20 or 30 dead. And it was shocking to the world, and gave us the intention, showed us the intention of the Ukrainian government.

RS: Well, the real issue here—and it’s interesting. I want to talk about one of my favorite Oliver Stone movies, which doesn’t get the respect—I mean, you’ve won all these Academy Awards, I mean, three I think, and all sorts of honors. But I liked your movie on Alexander. And what I liked about it, and what I like about the whole question of Alexander, really goes to the central tension in human history: what is the role of partisanship, of patriotism, of nationalism?

And something has happened. It was interesting, in the dispute—you know, Aristotle, of course you know, was Alexander’s teacher, and then advisor. And Aristotle betrayed, in really the pursuit of ethics, when he advised Alexander to be an imperialist, really. And in regard to the Persians, he said, you know, treat the Greeks, all of the Greek cities and so forth, as your family, as your friends. But treat the non-Greeks—that was the Persians then, basically—as beasts and vegetables, and they have no rights.

And Alexander, because he was out there the way Oliver Stone was out there, but you were a grunt and he was leading it, and you were in Vietnam and you saw the humanity of the Vietnamese; my understanding is Alexander said, hey, these are people; they’ve got brains; maybe they could cooperate with us and so forth. It was an interesting moment.

The U.S. is kind of in that position. We as a culture only accept our own legitimacy, our own nationalism, but we don’t call it nationalism; we call it internationalism. And anybody else in the world who has nationalist concerns—beginning with the Chinese and Russians, but it extends to anyone else—their nationalism is always threatening, is always illegitimate.

And to my mind, that’s the issue here. Not to—I don’t want to tear down Ukrainian nationalism, and I don’t want to overly boost Russian nationalism. But you have, as you point out, in Ukraine you have people there who think that they are identifying with Russia. And you have to worry about what happens to them, and you have a clash of nationalisms. And the basic U.S. position is that we are not nationalists; everything we believe in is universal. It’s the definition of freedom and the good life.

And anybody who disagrees—and that’s really what that Chinese-Russian statement was all about. These two countries—which by the way are closer now than they were under communism. There was a Sino-Soviet dispute when they were both ostensibly communist, but in their declaration last week of their common concern about the Western, NATO-led alliance, they’re saying that this hegemonic power of the United States, using NATO, is an enormous threat. And I think that’s something people don’t want to address. They think, oh no, we’re just pursuing human rights, which is nonsense.

OS: Yeah, absolutely. One thing that comes through in the interviews with Mr. Putin was he constantly refers to sovereignty—the sovereignty of Russia, the sovereignty of any country. It’s very important to the Russian nation. They have interests, they have national interests; everyone is allowed to have their national interests. We have never recognized their interests. On the contrary, we’ve done our best to spoil their interests, with our sanctions and our encouragement of the coup, and our financing of the coup in Ukraine.

We’ve tried to do the same thing in Georgia, and they fought a small war against the Georgians. And we’ve tried to do it repeatedly, possibly even in Kazakhstan recently. The United States is always looking to cause tension. That is the key: tension, call it a revolution, any of these things; raise the temperature and make it possible for a coup or a regime change, which is the objective of people like Victoria Nuland, who’s an undersecretary in the department of state.

So I think that, you know—we don’t recognize it, and we go and we play dirty games, very dirty games, to get what we want—which is, we want regime change in Russia. We’ve been referring to Putin as if he is Russia. If you look at all the news stories, they don’t even bother to say “Russia”; they say “Putin,” as if he is Russia, but that’s not quite the case. He has tensions from within, too. He has much pressure. There are factions in Russia. I know about that, and I think people underestimate the degree of difficulty in ruling a country as big as Russia.

If Putin does not act in certain ways, they will take him down. People will not abide by it if the Russians are embarrassed in Donbass. They will not. And I think America doesn’t understand that. They think that Putin makes up all these decisions himself, he sits there and he’s like a king, a monarch. But he’s not. He works with people. He has pressures. We have to understand that.

RS: Well, I think it really goes back to a basic arrogance which you as a young person had to confront. I mean, after all, you volunteered for combat in Vietnam; you’d been a schoolteacher there after you left Yale, and then before you went back, and then you left again. But the story of your life is really going between a notion of American innocence and virtue, and then being a soldier out there and seeing the killing of innocent people elsewhere. What Martin Luther King—here we are in Black History Month; we just celebrated Martin Luther King’s birthday. And most people, and certainly young people—you never hear it mentioned that Martin Luther King condemned the United States, at the time of his death and before that, as the major purveyor of violence in the world today. The major purveyor of violence in the world today, his government, the United States.

Now, what we had with Gorbachev—the reason I say we liked Putin, because Putin was not with Gorbachev, he was with Yeltsin; and Gorbachev was the naïve one, and Reagan promised Gorbachev that NATO would not expand. The whole reason of NATO was supposed to be a Cold War organization. Gorbachev thought he was ending the Cold War; he was very proud of this. And Reagan seemed to accept that. And instead, this Cold War organization of NATO has grown; it’s unwieldy, because it includes Turkey, it includes all kinds of countries that you suddenly find you’re not in agreement with, and a couple of them are closer to Russia in this respect. And you know, it’s hard to organize—it’s like organizing cats or something.

But the fact of the matter is, NATO was no longer supposed to be this vital organizing—what happened to the UN? In the joint Russia-Chinese statement, even though the Chinese had bad experience with the UN in the Korean War, they fought Korean troops and so forth—nonetheless, in that joint statement that Putin and Xi signed, they say: What happened to the UN? What is this NATO thing? What is this Western military alliance that is coming to our door? I think that’s the big issue of our time. And unfortunately, it’s only older people seem to have any memory of what the Cold War was supposed to be about, and what is it doing now.

OS: [Laughs] You’re very funny, Bob. That’s great, you have a lot of passion. I think NATO, as you say, has taken the place of the UN in many people’s minds. But it shouldn’t, because it’s an alliance with people from the West who seem to have one interest, one blinkered interest in taking over and changing things. In Libya, as I said earlier; in Iraq; in Afghanistan. They are interfering everywhere in the world, and Russia and China both recognize that and are worried about it.

And it’s a destabilization that we keep putting out into the world. It’s what I call a strategy of tension. The concept, for example, of saying in our immediate, day by day—since October it’s been a crescendo of imminent invasion of Ukraine by the Russians. Russian invasion, invasion—the word “invasion.” This is not an accurate word. Russia was not interested in invading Ukraine at all. What they are interested in doing is protecting the people of Donbass. That’s where this thing comes.

When the Crimean situation—if you look at the film I worked on, Ukraine on Fire, it’s very interesting; you see the people of Crimea at the hottest moment of the crisis. And you know what was happening? The nationalists, the Nazi groups, were coming into Crimea in order to cause trouble. And they saw them coming and they cut them off at the roads. We show it, how acute, how perceptive the Crimeans were. They knew who the enemy was. They stopped them from coming into Crimea.

And you know what the Ukrainian army that was stationed in Crimea did? The United States never tells you this in the press. They stayed in their barracks; they stayed in their barracks in Crimea. There was no violence at all. Not one person was killed. There was no gunfire. Crimea went into the referendum at peace. And the referendum, as you know, to rejoin Russia, carried by a huge amount, by ninety-some, ninety-seven, eight percent.

So why was there no violence? If it was an unhappy situation, and these people truly wanted to join the Ukraine, why was there no violence? That is a very interesting point, and people don’t recognize. Same thing is true about Donbass. People don’t recognize the murders that happened in Donbass, the artillery and the shelling, and the Ukrainian army moving in.

The whole situation last year—the only reason the Russian invasion has been hyped by the Western press is because the Ukrainian army upped its troop numbers and its armaments on the border of Donbass. So it looked like they were about to make a move on Donbass. They were getting javelin missiles from the United States, they were getting other weapons, and they were adding soldiers. They were trained by American advisors who are there, American—all kinds of specialists are in the country. Green Berets, Special Forces—it’s an operation. The United States has put more, has put a heavy amount of investment of our energy and time into destabilizing Donbass.

And that was supposed to be the move, I think, and I think it’s still a possibility. There was supposed to be a move in the winter, this winter, into Donbass. If they had done that, think about it, that would have been—that’s why the Russian troops were brought—actually the Russian troops were not brought to the border; that’s another lie. The Russian troops were where they were, in their barracks. Close to the border, but not on the border.

So when—follow my thinking here—when William Burns, the CIA chief, goes to Europe in October, he takes with him these satellite photographs, which he shows to the Europeans in the belief that they would follow us in our plan. The satellite photos were completely false. Again, they transposed the satellite photos to look as if they were on the border of Ukraine. And that was the aggression charge, that the Russian troops were about to invade—which was just simply not true; they were in their barracks. They were in their bases in Russia at that point. So you have this buildup of a fake invasion, a false flag invasion, and yet you keep hearing that; that’s what concerns me.

So think about it. If the Ukrainians go in—oh, that’s another thing they said. They said the Russians are planning a false flag operation in Ukraine to show that the Ukrainians are moving into Donbass. To show all the destruction. And that will be the reason for the Russian, quote, invasion. OK—so this is all staged. This is all staged, like an action, frankly, in Syria. We did this several times in Syria to blame the Russians for using poison gas. Same thing is true in Ukraine. They were looking—the reason the United States put that information out there that the Russians were creating a false flag and were going to invade, was because we were going to do it. We were going to support the nationalists to go into Donbass to attack the separatists. And if that had been the case, then Russia would have reacted.

But we were preparing the world to condemn Russia for that. We were preparing the world through our propaganda, which was extensive and worldwide, that Russia was the bad guy for having come in, tried to defend the Donbass people. It was a very disgusting but typical CIA operation. Typical of them, to put—in other words, they did the same thing numerous times now; they keep doing it. It’s annoying, because people don’t see the pattern. They did it with Julian Assange. They’re doing it with—they create this flags that they are doing, and they say, “he did it.” Do you understand what I’m saying?

RS: Oh, I understand it all too well. And I do want to bring up another, a book that you wrote—I forget your coauthor, but he was a well-known historian on the history of the Cold War. Help me here. Hello?

OS: Peter Kuznick.

RS: Yeah. And what is so interesting—I mean, look, you know, we’re older guys; I’m older than you. But the fact of the matter is, the notion of American innocence and exceptionalism has reasserted itself. And once again with the Democrats—they’re much better at this than the Republicans. The Republicans seem out for markets and business and so forth; the Democrats always have this fake idealism. And what you documented in that book was a history of false flag operations on both sides.

I want to reiterate this: I had hoped at this point in our history that nationalism would have receded; that people would not be dying over nationalism. And nationalism is always betrayed, until some big emperor comes up, and then they say, we’re not nationalists, we’re a civilization. But I mean, the Kurds didn’t get anything from U.S. manipulation of the Kurds in Iraq and Syria; they’re not getting a state. And nationalism was played within the old Yugoslavia, and where is the benefit there? Where is the benefit in Iraq?

So in the name of nationalism, whether we—now we claim we care about the Ukrainians. Do we really? Does the U.S. really care about—you know, it’s interesting. The only reason I’m in the United States, [Laughs] or at least part of me, is my mother was a refugee from the Russian revolution. She left after the revolution; she was a Lithuanian. And you know what? She trusted the Russian communists, more than she did the Lithuanian nationalists or the Ukrainian nationalists, to care about the Jews. Because they certainly didn’t care about the Jews before, and a very significant number of concentration camp guards and everything were drawn from the anti-Soviet nationalists in the Ukraine and Estonia, Latvia and so forth.

And so nationalism is always played; you’ll always find virtue on different sides. And I’m not here to celebrate Putin or Xi’s Chinese nationalism or anything else. I thought nationalism would decline. But as I see it, the main force in the world’s nationalist preoccupation is the United States. They are the ones saying, you know, we are not nationalists; we represent civilization, democracy, and freedom. But we’re going to back—you know, we’re going to back the Shiites against the Sunnis, because we think they’ll be better. Well, they weren’t better, and they also happened to be close to Iran. Or we’re going to back this faction against that faction. And nothing has—

OS: ISIS, too.

RS: Yeah, and nothing has to do with really giving voice to people. Giving voice to their concerns. They are just pawns. And I think, you know, we should really talk about the Democrats a little bit, because we drank from this Kool-Aid that somehow if we could just get these enlightened Democrats back in, we’d be in better shape. Well, the enlightened Democrats gave us the Vietnam War that you, Oliver Stone, got a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for, you know. And saw what folly that war was; that was a Democrat war. And then they went out with the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover, with the support of Lyndon Johnson, to get Martin Luther King to kill himself because he dared oppose that war, and said it was wrong. You know, so he was going to be expendable. As long as we’re in Black History Month, let’s bring that up.

But the fact of the matter is, there’s been no accountability. And the people who claim they are wise and believe in peace and democracy—no. They’re quite cynical. And to take somebody like Victoria Nuland, who was involved in the machinations that overthrew a Ukrainian leader who happened to get along with Russia—that was his crime. You know, he had other crimes and what have you—that wasn’t why he was overthrown. And the whole meddling, and the assumption that somehow you are on the side of virtue because you are the United States—you’ve lived your whole life with that, Oliver. You carried a gun for that, that hypocrisy.

OS: I know. I know, and listen, the behavior of the United States in all these instances that you mentioned has been reprehensible. And it’s hard for me to say it, but it’s our country, Bob. And we continue to question it for these reasons, and it seems that we keep going in this direction. We’re really blundering, blundering into a possible disaster, I’m talking about World War I-level, where because of our naivety—you know, they always say god protects puppies and innocent people and the United States of America. But, just, we’re blundering in a bad way.

RS: We’re not naïve. What are you talking about? The people may be caught up in what Huxley, the other dystopian writer, you know, in consumerism and they don’t give a damn about the world, and they don’t understand it very well. But our leaders are not naïve, they’re cynical. They’re deeply cynical. They know there was no Russiagate, and they know this is all machinations and everything. And they’re not interested, I don’t think for a second—I mean, Biden supported every irrational war. I don’t think for a second he has a greater compassion about the needs of people around the world than Republican hawks. I mean, what, the neocons, they started out as Democrats, then they became Republicans, then they became Democrats again. And they’re the same people in the State Department, and what they like is mischief. They think it’s virtuous. And it has to do with their careers, it has to do with power. I know it’s not naïve; they know darn well they’re not building a democracy there. And by the way, if you want peace and you want democracy, you’ve got to go against nationalism. You’ve got to contain it. And that’s true for Putin as well. If Putin keeps stoking nationalist feelings, that’s going to destroy Russia. And I must say, I thought this joint statement of the Chinese and the Russians was a game-changer. Because what they really said is, if we keep going down, the world goes down that road of nationalist division and stoking them and inventing them, you’re going to have disaster. And that’s what we’re talking about now, we’re talking about making not only Russia but China an enemy. You know, when the fact is the Chinese and the Russians would like to—because they’re conservative, basically, the Putin leadership—they want to follow the Chinese model. They want to produce stuff, they want to be in this market global economy, right? And that’s a vision based in trade, based on producing things, that one would hope would represent progress. Instead, we’re back in the darkest days of the Cold War because there’s a military-industrial complex, there are careerists, and they want war. They live off war.

OS: I can guarantee you that Mr. Putin is not at all interested in nationalism. He doesn’t see nationalism the way you’re seeing it. He sees national interests for Russia. And those interests are in the sphere of that area around Russia, which is [unclear] violated constantly by air exercises and land exercises, gigantic operations in the north and in the Black Sea, of Western allies, to warn Russia not to invade. The word “invasion”—it’s unbelievable, in my lifetime I remember Vietnam and I remember the New York Times writing about how dangerous Vietnam was because of the communists. But I’ve never seen the word “invasion” every day in the New York Times. Russian aggression, invasion—they did it like an Orwellian propaganda word, and they use it over and over, so that if there comes to be a fight, you will automatically register “Russian invasion.” That will be the first reaction, rather than “Ukrainian invasion of Donbass.” It’s a very sick game, and [unclear] It’s called the great game. It’s what these people do for a living; they play the great game. They raise the strategic tension wherever they can, the pot boils, and they take advantage of it.

RS: Well, I agree with that. The point I was trying to make about nationalism is that this will always be a force in the world. People find reasons to celebrate their own interests, their own culture, and attack others. The point of wisdom is to try to see past that, and to try to find common interests. And I do want to say—I want to end this by talking about your Putin interviews, because I hope anyone listening to this will watch that Showtime, four-part series, or will get the book based on it. And full disclosure, by the way—I wrote and introduction to your book, you might not remember I did. But I want to say, how—if we are thinking about war here, and what does this guy Putin want, and people ask me that all the time—you would at least have the obligation to take this work that you did, where you engaged this guy. And it’s absolute bull to say you don’t ask tough questions; that’s a lot of crap, you know. These were very good interviews. And to put somebody, this Masha Gessen who now writes for the New Yorker and is in the Ukraine kind of stoking this whole thing—for the New York Times to really, dare I say it, just pee on your work—it was just awful. And not, by the way, telling; there was no great revelation there. But the idea that we don’t have to—like reading this declaration. Any serious person should read the Chinese-Russia declaration. You may disagree with all of it, but you’ve got to read it. Five thousand words. What are they talking about? How did these two very different countries—which by the way had racial tensions historically, didn’t get along even in the heyday of communism, were shooting at each other. I happened to go from Russia to China, I was there during the Cultural Revolution, I know how they were at their border and everything else, I was in Vietnam as well. So somehow or other, they’re alarmed about us. They’re alarmed about American hegemony. And you know, one is a communist country—China, still; one is an anti-communist country, Russia, I don’t think there’s any question; Putin does not want a return to any kind of communist state of any sort. And yet this is a cry for reason, this statement saying, what are you guys doing? What is this Western alliance? Do you still think you can control the world and not pay attention to what we’re concerned about? And it’s not going to work, for that reason. You can’t blackmail them now.

OS: Yeah, thank god. But you know, objectively speaking, the United States—think about it, it’s just more secure from external danger than at any time since before World War I. We don’t have any enemies capable or desirable of using military force against us, our territory [unclear]. You know, China is not Japan, and Russia is not Germany in those years.

RS: Yeah, but Russia still has a very formidable nuclear force. And one of the things—remember, I wrote a book called With Enough Shovels about Reagan’s, the delusion during the Reagan administration about winning a nuclear war. And our indifference to something Putin talks a lot about in your interviews: the need for arms control, the need for stability. That concerns the Chinese as well. And all this Victoria Nuland stuff, and all this, you know, let’s bait ‘em, let’s bait ‘em, let’s stick our finger in the eye of the Russian bear—all that ignores the element of irrationality.

You brought up the missile crisis, and what John Kennedy learned was hey, it could all go kaput in a matter of minutes. And that’s the world we’re playing with now. And that’s why I bring up other people’s nationalism, and the pressure from their community. Don’t forget, it was Khrushchev, who was a Ukrainian, that gave Crimea supposedly to the Ukrainian state, which was like, you know, taking something from New Jersey and giving it to New York. They’re supposed to be part of the same country. It was Stalin who was a Georgian, right, who thought Georgia should be incorporated into greater Russia.

You know, so we just—look, I was in the Ukraine because a year after Chernobyl I was at the plant and I could not for the life of me tell who was Russian and who was Ukrainian. You know, and they had joint responsibility for creating and for mishandling this mess, OK? And it wasn’t like, oh, they’re the good guys over there, they’re actually more born in Kiev and not near the Russian—it was all garbage. They were all talking Russian, they all had the same power structure that they were part of. And so yes, it is largely an invention.

But what I’m saying is—again, let this be a positive part of this interview, and I want to end by talking about Alexander. Because I think it’s one of your great works, and it applies here. Because Alexander was the idea that maybe there could be a good emperor. But there can’t be. It’s a contradiction in terms. You can be enlightened with the best of Greek philosophy; you can have the best intentions; you can have the widest-open eyes. But at the end of the day, whether you’re the Roman emperor, whether you’re Alexander, or whether you’re the U.S. hegemony over the world, your stated intentions have nothing to do with your capacity to contain evil. It’s just the opposite. And that was the message from Orwell, invoking about the use of the enemy, and we ought to take it seriously.

OS: I agree. I think that’s very well said, Bob.

RS: All right. Well, thanks for doing this, Oliver. And again, can they still see the Showtime interview on Putin? Is it still up there?

OS: You can go to Amazon, you know, just regular Amazon, and you can rent it there. I’m sure you can rent it on iTunes and all the other platforms. It’s on Showtime also, but some people don’t have Showtime. Definitely widely available.

RS: All right. The Putin Interviews, and it’s a dozen interviews done over a two-year period. And I defy anybody to watch that. I watched it very carefully before I wrote an intro to the print version of this, you know; very carefully. I think I watched it six or seven times before I wrote a word there. I think it’s a marvelous piece of journalism. I really do. I think it’s a very important insight into a guy who, whether you like it or not, has power, has to be dealt with, has to be dealt with seriously. It doesn’t mean you cave or you give in or nothing matters. But the fact of the matter is, you won’t be able to just dismiss Putin in some simplistic terms if you watch this movie openly.

So let’s leave it at that. That’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. Christopher Ho posts these at KCRW. Joshua Scheer is our executive producer. Natasha Hakimi Zapata writes the introduction. Lucy Berbeo does the transcription. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

0 Comments