Assange is Free, But Never Forget How the Press Turned on Him

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange is free, having struck a deal with the United States Justice Department that will credit him for time served and allow him to go home. As someone who campaigned against his detention, I’m happy for him, his wife Stella, his brother Gabriel Shipton, and the other members of his inner circle who kept the case in the public eye all these years. They deserve to celebrate today.

Despite the fact that the plea was carefully crafted to say the state never proved its case, the Justice Department’s insistence on admission to the top count of violating the Espionage Act means this will remain a sword over the heads of anyone reporting on national security issues. Governments have no right to keep war crimes secret, but Assange’s 62-month stay in prison is starting to look like a template for Western prosecutions of such leaks. For instance, former Australian army lawyer David McBride was just sentenced to five years for leaking “classified” details of offenses by Australian Special Air Service (SAS) in Afghanistan, including the planting of “throwdown” weapons near the bodies of unarmed Afghans.

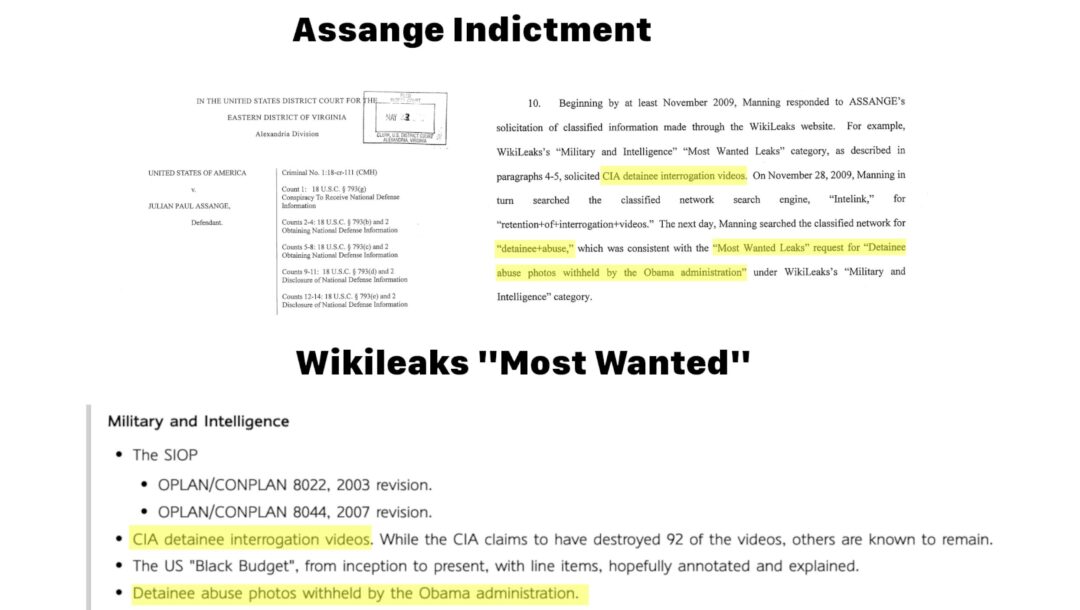

No one should be confused about the reason for the Assange indictment. Although coverage today focuses on solicitation of classified documents about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars whose publication supposedly “endangered lives,” the Justice Department made it clear from the start that its fury centered on efforts to disclose governmental bad behavior. The Assange indictment, for instance, highlights the Wikileaks request for “Detainee abuse photos withheld by the Obama administration”:

THE CRIME: Top, the superseding indictment of Julian Assange. Bottom, the Wikileaks “Most Wanted Leaks” request from 2009

The U.S. government is frosty about these topics for a good reason. The case record of detainees in places like Guantanamo Bay and the Bagram Collection Point in Afghanistan makes it clear the use of torture was far more extensive than the public realizes to this day, with one military coroner comparing the injuries of a dead Afghan prisoner to being “run over by a bus.” That’s another topic for another time, but the point is, the Assange case wasn’t just about the past. It’s significantly about the ongoing efforts to keep a lid on the extent of abuses connected to the War on Terror.

An argument can certainly be made that efforts to disclose things that are kept secret for good reasons must be punished. However, the classified nature of some of the solicited material wasn’t central to Assange’s case. The crime was soliciting “national defense information,” which can essentially be anything the government says it is. The use of the draconian Espionage Act will continue to send a message to anyone sniffing around any documents the state might find damaging, for any reason.

Many are calling Assange’s release a stunt, designed to help Joe Biden in his campaign against Donald Trump. It’s debatable how much this helps Biden, as there will be no shortage of voices reminding the public he had a chance to make this deal three years ago. His administration’s choices (and those of Trump’s) won’t be memory-holed easily, but I do worry about the public forgetting the role of another actor: the press.

When Assange was thought of as a vehicle for scoops about the iniquity of the George W. Bush administration, reporters loved him. Once he was seen as a critic of Barack Obama or as someone who helped Trump get elected instead of Hillary Clinton, they turned, and turned hard.

A quick review of some of the more incredible things said in print over the years:

The Guardian, November 27, 2018: Manafort held secret talks with Assange in Ecuadorian embassy, sources say This story remains the single worst piece of unredacted horseshit I’ve ever seen in a major news outlet, and that includes Judy Miller’s WMD pieces. The attempt to connect Assange to a secret Russiagate plot with the campaign of Donald Trump was based on a single anonymous source, who somehow saw something that evaded everyone else watching one of the most surveilled places on earth, the Ecuadorian embassy where Assange hid before his detention.

“A well-placed source has told the Guardian that Manafort went to see Assange around March 2016,” wrote Luke Harding and Dan Collyns. “Months later WikiLeaks released a stash of Democratic emails stolen by Russian intelligence officers.” Wikileaks replied that it was “willing to bet the Guardian a million dollars and its editor’s head that Manafort never met Assange.” This story was so obviously bogus that even those outlets that were the most aggressive reporters of Russiagate nonsense wouldn’t touch it, with Politico going so far as to publish a piece by a pseudonymous ex-CIA officer named “Alex Finley” suggesting that Harding was taken in by Russian operatives.

The Guardian never apologized for this piece and today is covering the hell out of Assange’s release, of course not mentioning its lengthy history of articles with titles like “The treachery of Julian Assange,” “Julian Assange like a hi-tech terrorist, says Joe Biden,” “The Guardian view on Julian Assange: no victim of arbitrary detention,” “From liberal beacon to a prop for Trump: what has happened to WikiLeaks?,” and countless others of this type.

Washington Post, May 28, 2019: “Assange is a spy, not a journalist. He deserves prison.” This gloating article by Marc Thiessen of The Washington Post gushed that, “at long last,” the “head of that enemy intelligence agency” known as Wikileaks was indicted and facing a possible 175 years in prison.

This column appeared in the same newspaper that had only just taken a long victory lap for publishing the Pentagon Papers via the movie, The Post. Here’s a section from Post coverage of the film:

“The Post” takes place in 1971 and chronicles how The Washington Post defied the Nixon administration to publish stories based on the Pentagon Papers, a secret government study about the Vietnam War.

The newspaper — along with the New York Times, which published Pentagon Papers stories and excerpts first — faces off against a Justice Department that believes publishing the information is a national security risk, a battle that ends up in the Supreme Court.

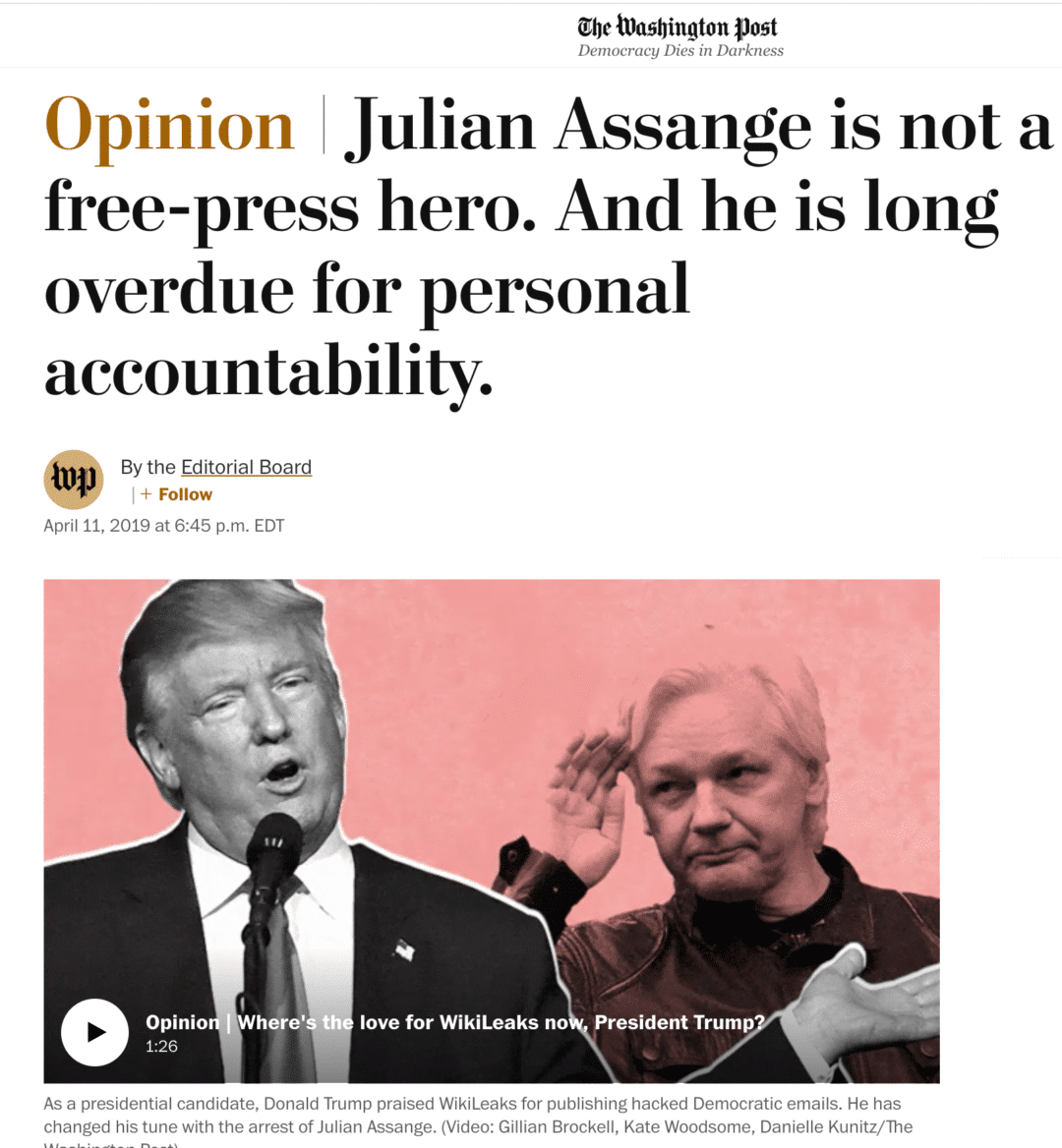

Thiessen wrote that Assange “engaged in espionage against the United States. And he has no remorse for the harm he has caused,” and insisted the difference between what Wikileaks did and the actions of a “reputable” paper is that Wikileaks “did not give the U.S. government an opportunity to review the classified information.” Lest anyone think this is just the opinion of one columnist, the Post editorial board was even more harsh than Thiessen, publishing a house op-ed saying, “Julian Assange is not a free-press hero. And he is long overdue for personal accountability.” The editorial illustration appeared to show Assange saluting Donald Trump:

Washington Post, January 5th, 2017: Julian Assange’s claim that there was no Russian involvement in WikiLeaks emails This one was mind-blowing. The Washington Post “fact-checked” Assange’s insistence that with regard to the DNC leaks, “our source is not the Russian government and it is not a state party.” Based on nothing more than the assertions of anonymous intelligence officials, they gave him “Three Pinocchios,” meaning the claim contained a “significant factual error and/or obvious contradictions.” As press watchdogs FAIR.org noted, it’s perfectly appropriate for journalists to be skeptical of Assange’s claims, and there was no forensic proof either way in this case, yet the Post reported the anonymous intel claims as gospel, noting that according to Brookings Fellow Susan Hennessey, “the U.S. intelligence community tends to be conservative in making public attributions.”

Bloomberg, April 11, 2019: If Assange Burgled Some Computers, He Stopped Being a Journalist Timothy O’Brien’s piece was one of many in which journalists conveniently forgot that they help sources disguise their identities all the time, and moreover that the charge that Assange offered to help Chelsea Manning conceal her identity by cracking a hash was never proven. More to the point, however, this was one of many pieces that departed from the tradition of reporters believing any story that’s true is worth doing.

Bloomberg wrote that Wikileaks and Assange “can’t shelter themselves inside the cloak of journalism and the truth” if they helped “hack” the U.S. government. “If he became a hacker and broke the law,” O’Brien wrote, “he was no longer a journalist and no longer just a messenger. He was a criminal.” Even stipulating that this particular offense did take place, this was a crazy attitude for a reporter to take, tsk-tsking Wikileaks as the criminal organization when the published leak included video of the U.S. army machine-gunning two Reuters staffers.

I had quibbles once about Assange’s “radical transparency” idea, not that I ever voiced them. As a younger reporter I wasn’t sure dumping huge caches of documents was the best way to do things. Over time however, I was convinced that the issue of secrecy and classification was a lot cloudier than officials made it out to be. I also had a disillusioning experience in the early Obama years when meeting with a federal law enforcement source about a totally unrelated finance issue, and hearing the person comment offhand that Assange was essentially a terrorist and the state should probably just blow him up. This was someone I liked. Over time I got the horrifying idea that this was the reflexive position of many in government.

As Assange himself (and media writers like John O’Day) pointed out, Wikileaks is in some ways an improvement over the heavily curated Western press model, in that the public can click through to raw documents to see if they’re reported accurately. The potential danger would be with operational material that might compromise a soldier or spy in the field, but our own courts heard testimony from a Department of Defense task force that found no instances of anyone killed as the result of a Wikileaks disclosure. That, and the site’s unbroken (as far as I know) streak of never publishing a phony document have helped make it the most influential breaker of news in our generation by far, something that is undeniably true no matter what your opinion of Assange or Wikileaks might be.

The news media’s behavior in the Assange story is incredible, something future historians will examine. Wikileaks partnered with major organizations like Le Monde, El Pais, The Guardian, The New York Times and others. Then, he became a villain, but when he was indicted by the Trump Justice Department there was some sympathy for him again. The behavior in some cases suggested press attitudes toward Wikileaks were guided almost entirely by partisan considerations:

Despite a few half-hearted words in support of press freedom, the major press outlets mostly didn’t see the recent Assange case as a potential threat to them, which had to be eye-opening for the public. It meant our current slate of news organizations could not imagine another Pentagon Papers-style event that involved them defying the national security establishment.

They just couldn’t see themselves in that role. This proves that in their current form, they are more proxies of government than advocates for the public. And if allowed, they will bury the role they did have in helping cheer this prosecution. Let’s hope it’s the last of its type, but I wouldn’t hold my breath.

0 Comments