Bellies of the Rich Swell Further on the Back of Hunger

by Colin Todhunter | Mar 25, 2023

It’s a zero-sum situation. The rich are robbing the poor to swell their coffers – and their bellies.

In April 2022, Oxfam reported a terrifying prospect of more than a quarter of a billion people falling into extreme levels of poverty in 2022 alone.

In its January 2021 report ‘The Inequality Virus’, it also stated that the wealth of the world’s billionaires increased by $3.9tn between 18 March and 31 December 2020. Their total wealth then stood at $11.95tn, a 50 per cent increase in just 9.5 months.

According to Oxfam’s analysis, 13 out of the 15 IMF loan programmes negotiated during the second year of COVID required new austerity measures such as taxes on food and fuel or spending cuts that could put vital public services at risk.

Oxfam and Development Finance International (DFI) also revealed that 43 out of 55 African Union member states face public expenditure cuts totalling $183 billion over the next five years.

The world’s poorest countries were due to pay $43 billion in debt repayments in 2022, which could otherwise cover the costs of their food imports. Governments across the world are now largely under the control of international creditors after COVID policies resulted in (deliberately) triggering a multi-trillion-dollar global debt crisis.

Meanwhile, oil and gas giants report record-breaking profits.

It’s similar for the world’s biggest agribusiness corporations. They have made more in profits since 2020 than the amount that the UN estimates could cover the basic needs of the world’s most vulnerable.

A February 2023 report by Greenpeace International – Food Injustice 2020-2022 – exposes rampant profiteering at a time when war and lockdowns have contributed to food insecurity across the world.

Twenty corporations in the grain, fertiliser, meat and dairy sectors delivered $53.5 billion to shareholders in the financial years 2020 and 2021. At the same time, the UN estimates that $51.5 billion would be enough to provide food, shelter and lifesaving support for the world’s 230 million most vulnerable people.

Davi Martins, campaigner at Greenpeace International, says that we are witnessing an enormous transfer of wealth to a few rich families that own the global food system. This at a time when the majority of the world population is struggling to make ends meet.

Martins says:

“These 20 companies could literally save the world’s 230 million most vulnerable people and have billions of profit left over in spare change. Paying more to shareholders of a few food corporations is just outrageous and immoral.”

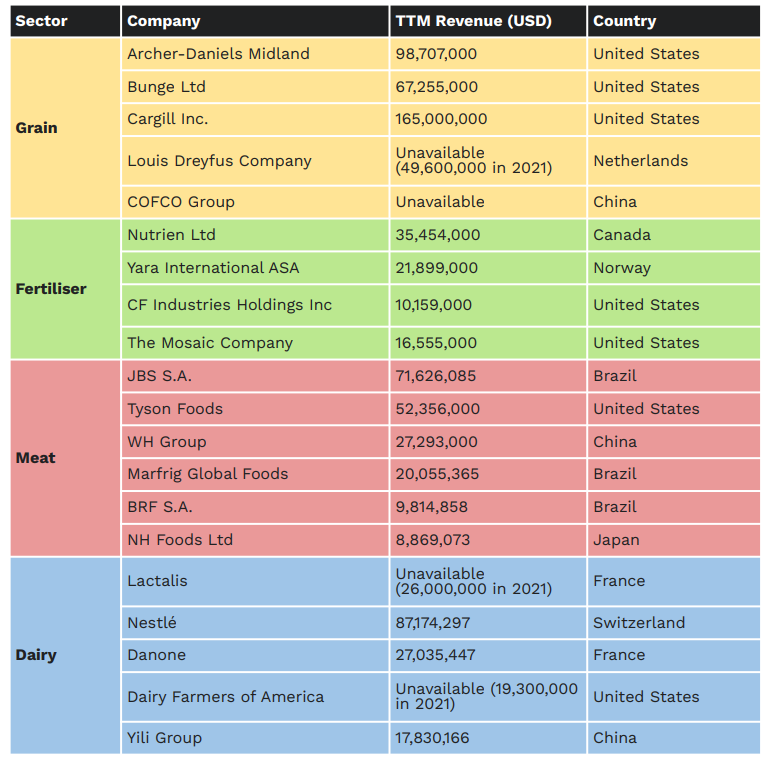

Covering the period 2020-2022 when COVID policies were in force and the war in Ukraine had begun, the report looked at the profits of 20 of the biggest agribusiness corporations and how many people have been affected by food insecurity as well as the extreme rise of food prices across the globe.

These ‘hunger profiteers’ exploited crises to gain grotesque profits. They plunged millions into hunger while tightening their grip on the global food system. One of the firms mentioned is Cargill – owned by 14 billionaires.

Together with Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge and Dreyfus – Cargill controls more than 70% of the world’s grain trade. None of these firms are under no obligation to disclose what they know about global markets, including their own grain stocks.

Table below from the Greenpeace International report listing the 20 firms included in its study.

Greenpeace found that a lack of transparency around the true amounts of grain in storage following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a key factor fuelling speculation on food markets and inflated prices.

Aside from manipulating markets and prices, these corporations also fuel food insecurity by pushing small-scale farmers and local producers out of the system. Smallholder farmers actually feed most of the world, unlike the type of industrial agri-enterprises global agribusiness serves (and sometimes owns).

Global agribusiness corporations never tire of telling policy makers that what they do is essential for feeding the world and ensuring food security. But the opposite is true.

They create or contribute to hunger, illness and malnutrition, displace rural communities, destroy smallholder agriculture, place farmers on seed and chemical treadmills and wreck and pollute ecosystems.

Aside from hollowing out or capturing key institutions to forward their agenda, they misleadingly conflate strengthening and expanding their global supply chains (destroying indigenous systems of production in doing so) with serving the food needs of the world (for insight into these issues, see ‘Food, Dependency and Dispossession: Resisting the New World Order’ on the website of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG)).

To prevent profiteering on such a grand scale and lessen the vulnerability of food supply and production to shocks (war, energy shortages, etc), a decentralised food system based on short supply chains is required. This would be based on the principles of localisation and strengthening smallholder agriculture. What this means is food sovereign communities in which local people take ownership of seeds, land and water (commonwealth) and manage what is produced and how it is produced.

Governments and policy makers need to act now to protect people from the abuses wrought by giant agribusiness corporations. Greenpeace argues that without regulating and loosening the grip of corporate control on the global food system, current inequities will only deepen further. It adds that we need to change the food system – failure to do so will cost millions of more lives.

The Greenpeace report adds further weight to calls for governments at international, national and local level to put an end to corporate control and monopoly in the food system while instituting an international trade order based on cooperation and human rights instead of competition and coercion.

0 Comments