Elephant in a China Shop by Electric Art

Meet the Clumsy Elephant in a China Shop: Can Tonsil Removal Provoke Polio and Autoimmune Disease?

by Tessa Lena | Jul 26, 2023

This story is about the wisdom of the skeptical peasant’s nose. It is also about how The Science constantly changes, and the people who have trusted the confident tone of the old science marketing brochure get hurt and mercilessly tossed out.

You know how I keep saying that modern medicine is much like a very clumsy elephant in a china shop? I keep saying it because there is never a lack of self-confidence and exclamation points in the medical marketing brochure. (Case in point: lobotomy used to be touted as a miracle “surgery for the soul”.) And yes, in acute situations, modern medicine is a godsend. But when it comes to understanding of the interconnectedness of different body parts and various mysterious things that nature knows and we don’t, the scientists are babies. And often, they are very confident babies with a strong drive for career growth and a very impressive marketing brochure.

The philosophical problem is that our civilization runs on intellectual arrogance and abstract thought. Arrogance alone is sufficient to lead the people astray. But of course, arrogance is not alone in that shop where the elephant is dancing like a klutz. Arrogance is accompanied by corruption, greed, indifference to other people’s suffering, and love of power.

By the way, if the experts were to humbly offer their latest take on health and not pressure people into going along—fine. That’s fair. But they don’t stop there. And since this article is about polio, and the polio epidemic is strongly linked to the use of DDT, here is a demonstration of the marketing brochure.

And here is a totally upside-down marketing brochure promoting the use of DDT to fight polio (!!!). (As a side note, let us not forget the mysterious “long polio,” i.e. post-polio syndrome.)

Tonsillectomy and polio

Not that long ago, tonsillectomy (tonsil removal surgery) was the fad. It was a very common—certainly safe and effective—procedure that many kids underwent.

Then the scientists found out that tonsils played a unique and important role in our immune response. Furthermore, they found that tonsils greatly helped in launching defenses against polio. Oooops.

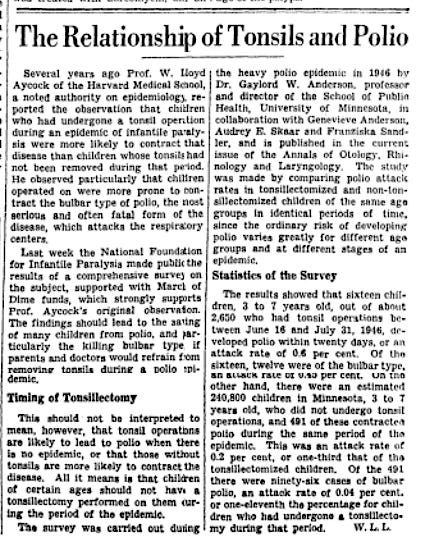

Here is Time Magazine, none the less (from 1942):

Five of the six children of an Akron family had their tonsils out one day last summer and within 48 hours all five came down with infantile paralysis. Three of them died. The sixth child did not contract paralysis. There had been no epidemic of the disease in Akron and none followed. A group of researchers from the University of Michigan, Western Reserve University and Akron’s Children’s Hospital investigated this puzzling case, published their findings last fortnight in the A.M.A. Journal.

The investigators discovered that the infantile paralysis (poliomyelitis) virus was present in the feces of the sixth child. They also found the virus in two groups of cousins with whom the children had come in contact, and in one family of neighborhood playmates—ten children in all. Yet none of these children, though harboring the polio virus, got the disease.

The researchers conclude that in the case of the five paralyzed children the tonsil operation was “the precipitating factor,” warn doctors and parents that tonsil operations are dangerous during the poliomyelitis season (summer and fall), even though the disease “is not notably prevalent in a community.” Probable connection between tonsillectomies and poliomyelitis: nerves injured by surgery are more susceptible to polio infection, so that the latent virus could travel readily from the injured throat nerves to the medulla oblongata, where the spinal cord enters the brain.

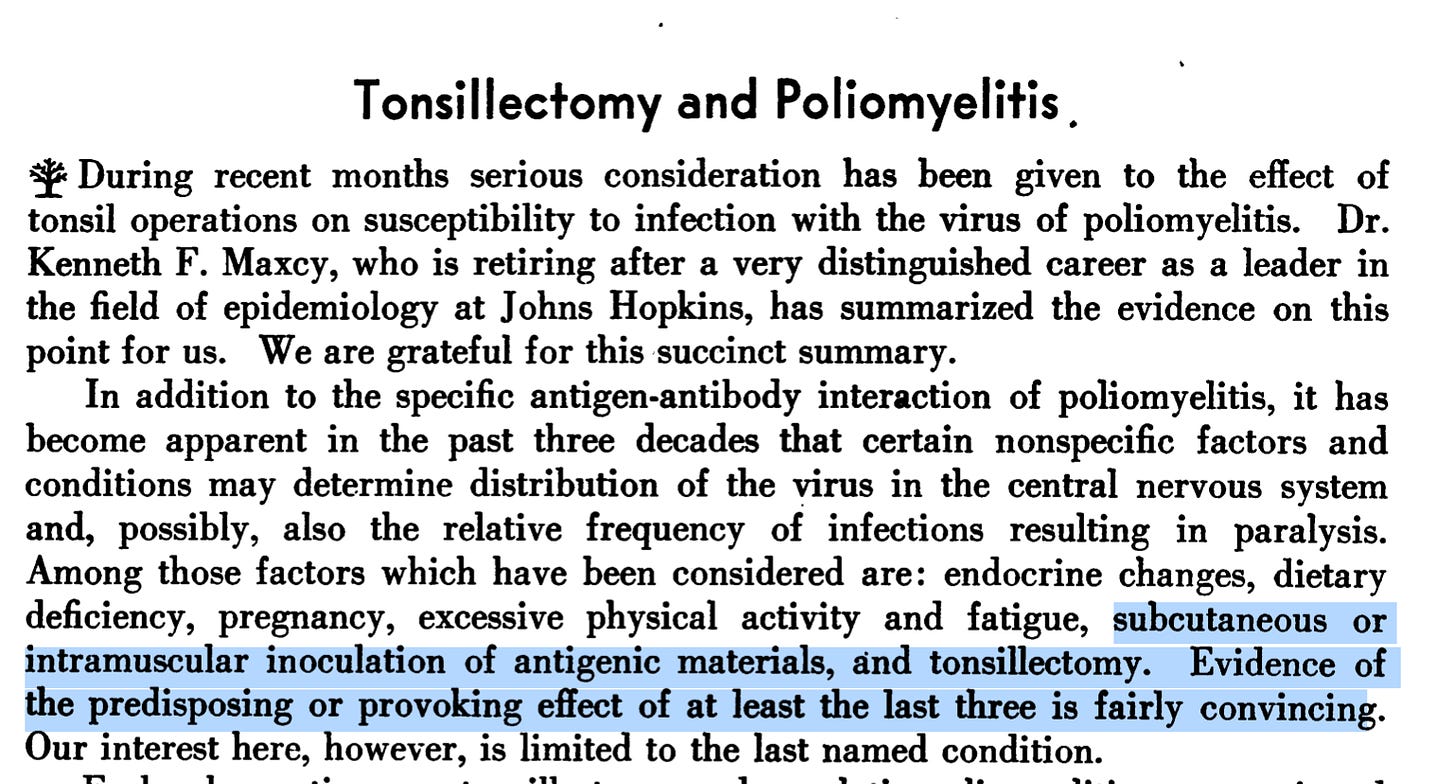

Here is Cambridge University (2013), addressing the association between paralysis and both tonsillectomy and childhood vaccines:

In 1980, public health researchers working in West Africa detected a startling trend among children diagnosed with paralytic polio. Some of the children had become paralyzed in a limb that had recently been the site of an inoculation against a common paediatric illness, such as diphtheria and whooping cough. Studies emerging from India seemed to corroborate a similar association between diagnosis of polio and recent immunisation.

These reports reignited a debate known as the theory of polio provocation that has waxed and waned since the early 1900s – and, at times, shaped immunisation policy. The theory of polio provocation argued that paralytic polio can be provoked by medical interventions, such as injections or tonsillectomy. The controversy that surrounded the debate forced medical professionals into the uncomfortable position of considering whether programmes and practices intended to prevent some illnesses might be also causing another.

Here is the Lancet (2014):

During the 1940s and 1950s, physicians and public health researchers in the USA, UK, Canada, and Australia sought to understand the nature of polio and how it attacked the grey matter of the spinal cord. Through clinical observation and reporting, older causation theories, which implicated poor sanitation or immigrant populations, were slowly replaced by a range of new possibilities, such as the effect of fatigue, diet, or hygiene. While personal characteristics and precipitating factors were examined, some physicians noticed a correlation between certain medical interventions and polio paralysis.

One of the first medical procedures implicated in the causation of polio was tonsil surgery. A study of more than 2000 case histories in the 1940s by the Harvard Infantile Paralysis Commission concluded that tonsillectomies led to a significant risk of respiratory paralysis due to bulbar polio [emphasis mine]. Although proponents of the theory did not entirely oppose tonsillectomies, they cautioned that such interventions should be avoided during epidemics. Reflecting the growing body of evidence that tonsillectomies could provoke polio, many doctors in the USA adjusted their surgical procedures to account for disease-endemic factors. “The policy of the United States Army”, Major-General E A Noyes acknowledged in 1948, “has been to stop tonsil and adenoid operations during epidemics”. Even though laboratory technology at the time was not sufficiently advanced to unravel the mechanism, published evidence affected clinical practice.

Concerns about tonsillectomies coincided with indications that paediatric injections could also incite polio paralysis. Evidence of this correlation was first published by German doctors, who noted that children who had received treatment for congenital syphilis later became paralysed in the injected limb. Although further studies from Italy and France corroborated this link, it was not until the end of World War II that injection-induced polio emerged as a public health concern. The application of epidemiological surveillance and statistical methods enabled researchers to trace the steady rise in polio incidence along with the expansion of immunisation programmes for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus [emphasis mine]. A report that emerged from Guy’s and Evelina Hospitals, London, in 1950, found that 17 cases of polio paralysis developed in the limb injected with pertussis or tetanus inoculations. Results published by Australian doctor Bertram McCloskey also showed a strong association between injections and polio paralysis. Meanwhile, in the USA, public health researchers in New York and Pennsylvania reached similar conclusions.

Here is the New York Times (1950):

And here is American Journal of Public Health (1954, PDF)

Tonsillectomy and autoimmune disease

As a side remark, tonsillectomy may also be a factor in autoimmune disease. Here is a quote from a paper (2016):

The incidence of a group of autoimmune diseases was higher in individuals operated with a tonsillectomy. Immune dysfunction due to tonsillectomy may partly explain the observed association. However, the underlying mechanisms need to be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

When the experts tell us that any medical procedure is safe, they typically don’t understand the entire picture even when they mean well. It takes decades to connect the dots and calculate the relationships that at the time of the sales pitch the scientists aren’t aware of.

The vaccination industry is a great example of blowing smoke. From day one, it’s been based on adventurous assumptions, wobbly testing, and wishful thinking. We are used to hearing all day how vaccines save lives—but once you start digging with honesty, you discover mostly Theranos. A successful case of Theranos. Turtles all the way down.

And they say that the skeptical peasant is the stupid one?

0 Comments