Corruption and COVID: We Are Not ‘All In This Together’

by Michael P Senger | Feb 23, 2023

For those who live in developed democracies, the corruption that plagues so much of the world can be difficult to understand. What is “corruption” exactly, and what causes it?

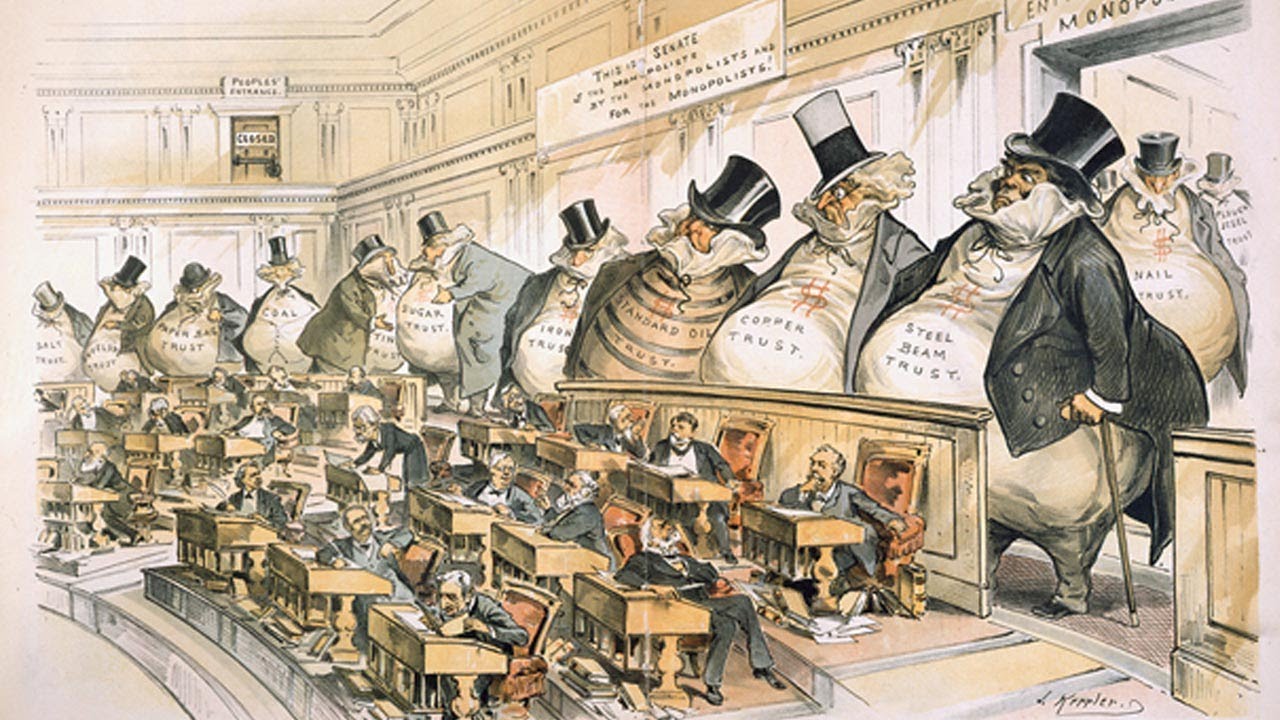

At a high level, corruption stems from the systemic disrespect of a nation’s institutions and legal system, especially by those in power. But while the causes and roots of corruption are complex, the results are consistent and banal. The hallmark of virtually all corruption is “playing dumb”: Officials make decisions in their official capacity that are inexplicably poor for the institutions and the public which they’re meant to represent, but which actually benefit another party in which the corrupt official has an interest. The poor decisions of these corrupt officials, and the connections that led to them, are protected from legal scrutiny either by dysfunctional civic institutions or by other corrupt officials.

Fortunately for those of us in the developed world, while there are important exceptions, most of our officials tend to conduct themselves in a decent and honest manner.

That is, of course, until March 2020, when governments across the western world decided to shut down all of their economic and social institutions for an indefinite period, ostensibly on the belief that the lockdown of one city in China had effectively eliminated a fast-spreading respiratory virus from the entire country (but nowhere else). They then proceeded to import a swathe of illiberal “public health” mandates including forced masking, mandatory testing, quarantine facilities, and digital vaccine passes for everyday activities, none of which did anything to control COVID, but which did terrify the public into normalizing and extending these psychologically self-perpetuating policies.

“We have only ourselves to blame!” “We have to take personal responsibility.” “This is the power of fear!” “This is the endgame of modern liberalism.” “Don’t blame China. Blame our own governments.”

Anyone who’s been at all involved in the debate surrounding the response to COVID has seen these kinds of overtures with some frequency. Superficially, these calls for “personal responsibility” have a veneer of virtue—even nobility. But given the particular nature of the crimes committed during the response to COVID, these calls to personal responsibility are insufficient. In fact, owing to the particular nature of corruption, calls for “personal responsibility” can even be used by corrupt officials or their agents to avoid scrutiny for their actions.

1. To collectively “blame ourselves” for decisions made by a small number of individuals is to be ruled by those individuals.

Historians who’ve studied the subject of divine rule have identified no particular point in time in which the concept of divine kingship could be said to have arisen. In fact, across continents, with some exceptions, wherever human civilization arose, there were god-kings. That is to say, whenever humans organized themselves into agrarian civilizations of significant size, a strongman was liable to claim the civilization as his own, and the population was forced to treat him and his will as divine.

Under this traditional system of divine kingship, in all matters public and private, the will of the ruler was the will of the people. For a mistake to be made was definitionally impossible. For the ruler to be questioned or “blamed” was taboo to even think—equivalent to questioning a god. Should the will of the king result in peril or even death for anyone in the kingdom, even deliberately, then they had only themselves to blame.

Over countless centuries, mankind developed institutions to check this kind of centralization of power. The purpose of these institutions was best expressed by the thinkers of the western Enlightenment. In the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains.” And in those of John Locke: “Men being, as has been said, by nature, all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.” And as James Madison put it:

“If Men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and the next place, oblige it to control itself.”

The goal of these institutions was to establish checks and balances that preserved the rights and the will of individuals, empowering them with at least some organizational structure should the need arise to hold those in power accountable under the law.

But these institutions are meaningless unless citizens utilize them. Should the public instead choose to accept the decisions of those in power as a substitute for their own free will, then even the best-designed institutions are powerless. It is thus in the interest of any would-be tyrant or ruling clique, through either propaganda, coercion, or demoralization, to convince the people to accept their decisions as a substitute for their own will. Once the public accepts decisions made by any particular individual or group as a substitute for their will, then they are effectively ruled by them, just as they were ruled by the god-kings of ages past.

Personally, I never accepted the COVID lockdowns of 2020 or any of the mandates and dictats that followed. I will not blame myself for these policy catastrophes, nor do I believe my fellow citizens who did not support these polices should blame themselves. On the contrary, I believe these policies were illiberal and fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system, and I see them as an underhanded means of superimposing decisions instigated by a small and conspicuously anonymous clique for the will of the people. I therefore believe that our institutions should be utilized to demand a comprehensive inquiry into the provenance of these policies, so the intentions and lawfulness of the clique who initiated them may be examined by the public.

2. Those who call for us to “blame our own governments” may be overly-optimistic about the chance of seeing justice based solely on the policies themselves—or, alternatively, overly-pessimistic about the chance of getting any justice at all.

One of the most common complaints I receive about my work is that we can’t “blame China” for the response to COVID and should instead “blame our own governments.” This has always baffled me, because the whole point of my work is that the response to COVID was so inexplicably awful as to reveal our governments to be corrupted to an unprecedented degree, and we should therefore heap blame on our governments even to the point of launching investigations. That said, the argument that we should “blame our own governments” for the response to COVID comes up enough to warrant examination.

In the United States, there is no historical precedent for prosecuting an official on the sole basis that a policy the official implemented was so bad. The constitutionality of a policy can be challenged in court, but even if successfully challenged, the policy is simply reversed; there are no repercussions for the officials who implemented it aside from losing their office. Even in the cases of the worst policies in American history, such as the Trail of Tears and Japanese internment, there are no instances in which officials have been charged simply for issuing policies that were extremely bad.

The lockdowns and mandates that were implemented during the response to COVID were extraordinarily illiberal and destructive. Those who call for us to “blame our own governments” may be thinking that individual officials should be charged simply for being so ethically vacuous as to implement such awful policies. But there is no historical precedent or legal basis for such a charge. Of course, the officials should be removed from office, but if the goal is to charge an official for a policy that he or she implemented, then it’s corruption or bust. Legally, there is no alternative.

On the other hand, those who call for us to “blame our own governments” for the response to COVID may be implying that obtaining justice for what was done is impossible, and that we should therefore begrudgingly accept whatever our governments decide to do. But I find this view fatalistic; civic activism has always been necessary for our institutions to function properly.

Significant evidence of corruption and malfeasance during COVID has already begun to emerge. A well-designed inquiry into the response to COVID, if demanded by the public, could reveal criminal wrongdoing on the part of key officials who instigated that response. And a finding of corruption on the part of one or more officials during COVID would likely to lead to more investigations in other states and countries—a domino effect that could cause the entire conspiracy, if any existed, to unravel. On the contrary, to simply accept our fate, however begrudgingly, would be exactly what the conspirators would want.

Finally, those who call for us to “blame our own governments” may be thinking the illiberalism of the response to COVID proves our constitutional republic system is broken. But there’s no better system on offer, nor is there anywhere near the political will to replace our system. The response to COVID has revealed the need for important long-term reforms, such as limiting emergency powers and the legal purview of “public health.” But aside from those long-term reforms, fixing our institutions means working within the system we have.

3. Because of the specific nature of corruption, the criminality of any given action by an official depends entirely on whether it was influenced by an outside interest.

Because of the nature of the crime of corruption, the same action taken by an official would not be a crime if that action was devised solely of the official’s own free will, but would be a crime if it was influenced by the official’s outside interests. Counterintuitively, it can thus be in the self-interest of a corrupt official, or those protecting the corrupt official, to insist that he or she take “personal responsibility” for his or her actions. The following is an example to illustrate this phenomenon (any resemblance to real persons, places, or events in this example are purely coincidental).

In response to news about a novel virus, Governor Gavin Dandrews believes that all churches in the state of Danistan should be indefinitely shut down. Dandrews discusses his plan with his wealthiest funder, Robert Banks, who thinks it’s a great idea. Mr. Banks takes the idea to his newspaper, the New Donk Times, and journalist Donald Squealer pens a very convincing piece arguing that shutting down all churches in Danistan is the right thing to do. But years later, to everyone’s dismay, it turns out that shutting down all the churches in Danistan did nothing to stop the spread of the virus.

In the above example, all the individuals involved showed very poor judgment in calling for the shutdown of all churches in Danistan. But no one is guilty of corruption. On the other hand, take the following example.

Robert Banks would like to produce his latest uPhones at the lowest possible production cost. Mr. Yi, General Treasurer of the city of Muhan, can produce the uPhones at the lowest production cost, but on one condition: Mr. Banks must endorse Mr. Yi’s model for the response to an outbreak of a novel virus, which involved shutting down all churches in Muhan to eliminate the virus—or so Mr. Yi claims. Mr. Banks agrees, and in return for Mr. Yi’s producing the uPhones in Muhan, Mr. Banks tells Governor Dandrews that, in exchange for ongoing campaign funding (and a little something in the Panama fund), they need to copy Muhan’s response to the virus by indefinitely shutting down all churches in Danistan. Mr. Banks also contacts Donald Squealer at the New Donk Times to pen a very convincing article that shutting down all churches in Danistan is the right thing to do. Later, between bites at his favorite restaurant, the Dutch Laundry, Governor Dandrews expresses remorse that shutting down all churches in Danistan did not slow the spread of the virus.

In this example, now we can see the corruption that’s gripped the once-innocent state of Danistan. The result is the same—all churches have been shut down to no avail—but now we can see that they didn’t do it because they actually thought it would stop the virus, they only did it so that Mr. Banks could keep producing low-cost uPhones in Muhan!

Intrepidly, we call for an investigation into corruption in the matter of the shutting of churches in Danistan. But upon hearing of our campaign, Squealer pens a compelling piece in the New Donk Times imploring Governor Dandrews and his fellow citizens to take personal responsibility for what’s transpired. Everyone had been gripped by fear, Squealer argues. “Don’t blame Muhan. Blame our own government, right here in our beloved home of Danistan.” Governor Dandrews takes the stage and personally assumes responsibility for shutting all Danistan’s churches, tearfully explaining to the crowd that it was the best decision based on what he knew at the time. The citizens of Danistan applaud this display of statesmanship and put the matter to rest. By the next election, hardly anyone remembers the affair.

Here, you can see how the poor citizens of Danistan have been played. Squealer and Governor Dandrews may have convinced the people that they and their government were taking personal responsibility for the closure of churches in Danistan. But it was never actually about taking personal responsibility, it was only about avoiding an investigation that would have revealed the churches had been shut so that Mr. Banks could keep producing low-cost uPhones in Muhan.

Conclusion

The prosecution of corruption is an established and necessary part of our institutional framework. In certain, extreme circumstances, if the promulgation of a policy has been influenced by an ulterior interest, then it must be considered criminal. Official decisions that exhibit the hallmarks of corruption by being otherwise inexplicably catastrophic—or based on inexplicably naïve premises, such as the treatment of China’s COVID data as real—cannot go ignored.

If corruption is not properly prosecuted, then constitutional democracy will inevitably be consumed by regimes or criminal networks that are willing and able to use methods such bribery and blackmail to affect policy. No amount of institutional tinkering could avert this.

Certainly, we should all take personal responsibility for what transpired during COVID by examining our society, our institutions, and ourselves to make sure nothing like this ever happens again. But the most important way we can take “personal responsibility” for the response to COVID is by making sure the officials who instigated these policies see a comprehensive inquiry into their decision-making.

Those who initially acted to impose lockdowns during COVID took bold steps that they knew would indelibly affect millions of lives. Given their confidence, they should be more than happy to reveal themselves and explain their motivations and reasoning to the public. We’re waiting.

0 Comments