Escaping the industrial nightmare

Escaping the industrial nightmare

by Paul Cudenec | July 5. 2024

Whatever happens in Sunday’s bitterly divisive parliamentary elections in France, we can be sure that the next government will be committed to economic growth and technological progress.

As the excellent monthly newspaper La Décroissance (“Degrowth”) never ceases to point out, politicians from all sides of the supposedly all-embracing “political spectrum” (including so-called “greens”!) speak as one in condemning the absurd, reactionary suggestion that the future shape of the country should not be dictated by the endless quest for yet more profit and production.

Fortunately there is a significant undercurrent of French thinking that fundamentally challenges the narrative spun by the many heads of the financial-industrial Hydra.

The fact that there even exists a monthly (and very widely available) newspaper promoting degrowth is an indication of the significance of this movement, as is the anger that it seems to incite not just on the mainstream wing of the criminocracy, but also among its pseudo-radical proxies, who use all the usual smear techniques to attack it.

Because the ideas voiced by this undercurrent are generally not accessible to the English-speaking world, I thought I would write reviews of two recent books issued from that milieu.

The first of these, that I will describe in this article, is interesting in that it comes from the traditional anarchist movement – Les Editions du Monde Libertaire, the publishing wing of the Fédération Anarchiste.

I tried to get UK anarchists interested in degrowth a decade ago, but didn’t meet with much enthusiasm, despite what is for me an obvious ideological compatibility.

In La Décroissance libertaire, une étape cruciale (“Libertarian degrowth, a crucial step”), [1] Jean-Pierre Tertrais concedes that, historically, mainstream anarchism has tended to take the “scientific” (and Marxist) line of supporting “the development of the productive forces”.

Indeed, there were one or two points in his book where I feared that he himself was shying away from an outright condemnation of what Jacques Ellul called Technik!

But he continues: “Libertarians [by which he means anarchists] have often been the first to express suspicion regarding the growing grip of Technik on everyday life”. [2]

“Only libertarian principles have the capacity to get humanity out of the dead end in which it has gone astray: refusal of authority; rejection of all domination and exploitation; free association of producers; mutual aid and co-operation, federalism…” [3]

I was pleased to see that Tertrais cites not only Ellul, but also fellow organic radical inspirations William Morris, John Ruskin, Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy, Peter Kropotkin, Gustav Landauer, Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and George Orwell.

And he shares the orgrad conviction that we can learn much from the pre-industrial past when imagining a healthy future beyond the current nightmare.

He says it’s not a question of believing in a lost “golden age” but of understanding the appeal and advantages of a society based on craftsmanship and connection to the natural elements.

Tertrais describes “a rough life, but one attuned to the rhythms of plant, animal and human life, punctuated with solidarity, camp fires, festivals” and founded on “the choice of keeping a balance between a social group and the territory it occupies, whose resources are always limited”. [4]

He contrasts this with the artificial and alienated lives that we are forced to lead in the modern industrial prison-camp world.

“This race for growth, founded on the exacerbation of a climate of competition, on permanent injunctions to go beyond our limits, contributes largely to the ‘alienation’ of the human being, to dependence on techno-science, to exhausted workers (stress, burn-out, depression, suicide) with degraded health (modern pathologies, civilisational diseases)”. [5]

In the face of this, he is scathing about those who claim that the “solution” to contemporary problems can come from racing even further down the road to industrial expansion, with their absurd claims that “we need more growth to repair the damage caused by growth, more Technik to correct the ravages of Technik!”. [6]

And he condemns the “techno-optimism” of the political classes, with their calls for “carbon neutrality”, resilient smart cities and proposals to modify the climate.

Under “sustainable development”, he observes, consumption continues to rise and “green” technologies depend on rare resources like lithium and cobalt whose extraction involves odious exploitation of workers and serious pollution of the natural world. [7]

Tertrais correctly identifies the very concept of “development” as being a primary source of the evil afflicting our world and describes how it fuels global imperialism.

The official narrative declares that “under-developed” countries are lagging behind and have to be helped to “catch up” with fully industrialised countries.

“This notion expresses the cultural imperialism of the western civilisational model and hides (badly) a post-colonial system for exploiting the resources and labour force of the global south to feed the hyper-consumerism of the north”. [8]

As I mentioned, the central importance, to the system, of the development/progress narrative is such that it cannot tolerate anyone challenging it.

Tertrais remarks: “Those who question the political, social and philosophical implications of technology are instantly accused of ‘technophobia’, obscurantism… of wanting to return to the candle”. [9]

“Massive adherence to productivism and the glorification of technological progress have prevented any critical perspective.

“The hyper-technologisation of our ways of life comes with countless ‘side effects’. Machines, which were supposed to free us from wearisome or constraining tasks, from the inconveniences of everyday life, have – despite the services they can occasionally provide – ended up producing a diminished human being”. [10]

So how does the author propose that we get out of all this?

In fact, he thinks the process is already beginning, with increasing numbers of people dropping out of their jobs and/or turning their backs on city life and seeking a different existence in the countryside.

He says that 600,000 to 800,000 people moved out of conurbations in France between 2015 and 2018, with Covid no doubt increasing that figure. [11]

How long that will be allowed to continue, with the global “managed retreat” agenda of forcing people out of the countryside and into smart cities, remains to be seen!

Tertrais writes about the importance of “going back to real life”, [12] and rediscovering a “DIY” style of living, including gardening, repairing, clothes-making and cooking. [13]

This would involve “listening to our real needs, living with little but with intensity, turning our backs on success, ‘progress’ (TV, computer, car…), prioritising family life, personal blossoming, rediscovering know-how and a sense of scale, reconnecting with nature, learning to manage our own time, enjoying the richness of social interactions, the sense of being useful…” [14]

This, though, is just the start, he explains.

“If the original motivation is not revolutionary as such, it can expand and assume a political dimension: questioning of paid work, hierarchy, competition, the market, an interest in self-organised collectives, forms of mutual aid, civil disobedience or popular education”. [15]

Anti-industrialism in France is not just an idea, but also a physical movement, which is probably best known for the ZAD (Zone à Défendre, “Zone to be Defended”) which successfully occupied an area of land near Nantes and permanently prevented the construction of a new airport.

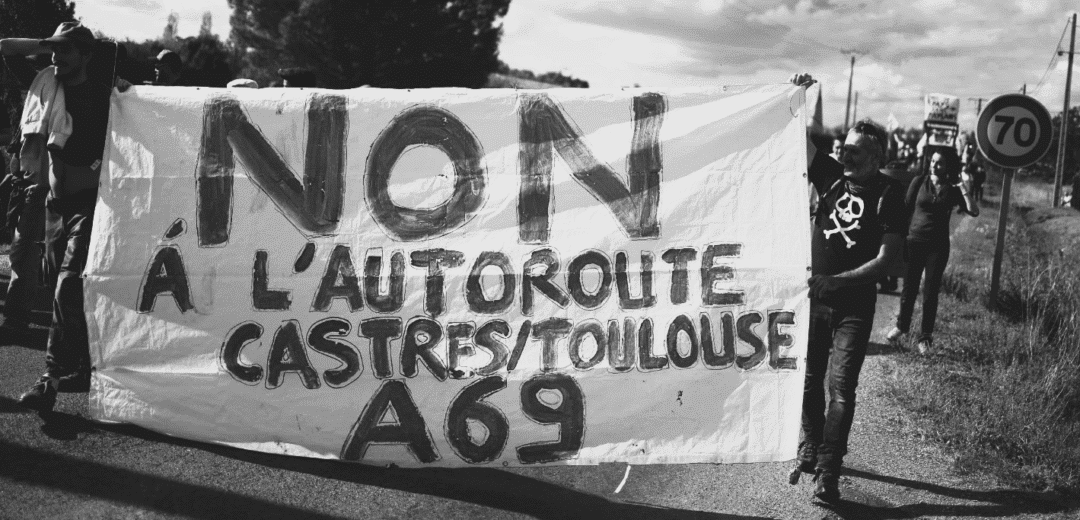

Currently there are important struggles being waged against a new motorway near Toulouse and against industrial-scale reservoirs that are being built all over the place.

“The land doesn’t belong to man. It’s man who belongs to the land”

Tertrais notes that those involved are “predominantly young people who, between hope and rage, have decided to break with a society whose values they reject and who seek to live otherwise”. [16]

He says the younger generation in France are politicised in a different way to their elders, “with two guiding values, freedom and respect”. [17]

While part of this struggle is essentially defensive – such as protecting allotments, opposing the expansion of a quarry or the concreting-over of the countryside [18] – there is also a pro-active aspect, taking the fight to the system.

Writes Tertrais: “Sabotage, which emerges from civil disobedience and direct action, is a growing craze.

“Faced with the limits of polite protest, more and more activists are turning to it… pipelines, surveillance cameras, speed cameras, phone masts (170 sabotaged in one year), transport infrastructure, cash dispensers, mega-reservoirs… the damage is accelerating”. [19]

“For so long considered unacceptable by public opinion, sabotage seems more and more legitimate”. [20]

PS. I will post a review of the second book I have in mind when I have finished reading it!

Subscribe to Winter Oak

Notes:

[1] Jean-Pierre Tertrais, La Décroissance libertaire, une étape cruciale (Paris: Editions du Monde Libertaire, 2023). All subsequent page references are to this work.

[2] p. 98.

[3] p. 8.

[4] pp. 54-55.

[5] p. 33.

[6] p. 38.

[7] p. 95.

[8] p. 20.

[9] p. 91.

[10] p. 96.

[11] p. 102.

[12] p. 80.

[13] p. 57.

[14] p. 104.

[15] p. 104.

[16] p. 119.

[17] p. 113.

[18] p. 118.

[19] pp. 119-120.

[20] p. 120.

0 Comments