Fear is the Real “Virus” (Addendum)

by Mike Stone | Oct 31, 2024

Shortly after I started the ViroLIEgy Substack, I wrote an article titled Fear is the Real “Virus,” focusing on how one’s mental state can profoundly impact their health. I examined how strong emotions like fear, leading to greater stress and anxiety, can manifest the very symptoms one fears—a phenomenon known as the nocebo effect. This effect occurs when negative beliefs create negative health outcomes. I provided evidence for the nocebo effect in action in the article Infectious Myth Busted Part 7: The Common Cold Vacation, where a patient’s belief that they should contract an illness in a transmission experiment resulted in the very symptoms developing. This happened after a nurse mistakenly told the patient, who was healthy two days after the injection, that they had received a cold filtrate rather than a sterile solution. Once corrected, the patient’s symptoms subsided almost immediately:

This was demonstrated by Alphonse Raymond Dochez in his paper Studies in the Common Cold. Oddly enough, this was the paper that convinced Dr. Andrewes that the common cold was due to a transmissable “virus” to the point where he adopted the views of Dr. Dochez as the CCU’s working hypothesis. In the 1930 paper, Dr. Dochez not only noted that volunteers could convince themselves that they had a cold when they did not, he also stated that the filtrates, regardless of whether containing the assumed “virus” or not, caused stuffiness, sneezing, and headaches:

“It is very easy for an individual who is being used for a transmission experiment to believe that he has a mild cold although objective evidence is extremely slight or absent. Where, as in the beginning of our work, volunteers believed that we were trying to produce colds, they were self-convinced occasionally that they were suffering from a mild infection. This was much easier of belief as the filtrate in practically all the cases, negative and positive, causes some slight stuffiness of the nose, a little sneezing and occasionally slight headache.”

As an example, Dr. Dochez spoke about a patient who was given an injection of sterile broth without “virus.” When he was accidentally told by an assistant that he had failed to catch a cold, that night, the man began to suffer severe symptoms. When he was told the next morning that he had been misinformed about the nature of his injection, the man’s symptoms disappeared within an hour:

“It was apparent very early that this individual was more or less unreliable and from the start it was possible to keep him in the dark regarding our procedure. He had inconspicuous symptoms after his test injection of sterile broth and no more striking results from the cold filtrate, until an assistant, on the second day after injection, inadvertently referred to his failure to contract a cold. That evening and night the subject reported severe symptomatology, including sneezing, cough, sore throat and stuffiness of the nose. The next morning he was told that he had been misinformed in regard to the nature of the filtrate and his symptoms subsided within the hour. It is important to note that there was an entire absence of objective pathological changes.”

The power of the nocebo effect, which is where the belief that a negative outcome from a treatment or procedure actually causes the manifestation of that outcome and results in harm, is a well-known phenomenon. This was something acknowledged by researchers before, during, and after the CCU experiments. In the CCU’s intake form, they advised that “the volunteer should not be bound to think that he will develop symptoms after being given nose drops.” In fact, they admitted that “there is a good chance that he may not” as “some volunteers prove resistant to the virus inoculum anyway.” They admitted that “by and large, only about one third of all volunteers actually develop symptoms.” These symptoms are non-specific, and they are exactly the same as those attributed to hay fever and seasonal allergies. Thus, on top of the issues with patients manifestimg symptoms due to the belief that they may get a cold just from undergoing the experiment, the interpretation of a cold is entirely subjective which is why they utilized a double-blind set-up to try and mitigate “incorrect interpretations” by the researchers as well as to ensure that they did not imagine signs and symptoms that were not there. Just the action of injecting these solutions into the nasal cavities, regardless of whether they contain a “virus” or not, will result in symptoms such as headache, malaise, stuffiness, and sneezing, as noted by Dr. Dochez and the authors of the 1958 study. Thus, it can be easily concluded that it is due to the experimental procedure itself, along with the reaction, both physically and mentally, of the individual to the presence of foreign substances, that results in the occurrence of the non-specific symptoms which are then subjectively interpreted to be the common cold by the researchers based upon the inoculum given.

In the case of “Covid-19,” the belief in—and fear surrounding—the “threat” of a “novel virus” may have been the critical trigger that pushed many over the edge into illness. The incessant visual cues—daily death counts, lockdowns and curfews, social distancing markers, hand sanitizing stations, and masked faces everywhere—served as constant reminders to remain afraid. Added to this was the flood of conflicting information: How did the “virus” spread? Were asymptomatic carriers a driving factor? Did masks work? How long did vaccines provide “immunity?” Was the “virus” natural or a man-made bioweapon? It’s no surprise that in a time when much of the population was already teetering on the edge of poor health, an increased state of fear, stress, and anxiety could negatively impact their well-being. No invisible microbial “virus” is needed to cause illness and death when the very real, and highly contagious, “virus” of fear is at play.

This topic is crucial for understanding how dis-ease can spread rapidly, particularly in today’s world where fear propaganda is delivered daily by the pharmaceutically-funded mainstream media. Increased fear, stress, and anxiety may explain many deaths, as these emotions could exacerbate underlying health conditions worsened by emotional trauma. The fear of an unknown “virus” and the potential threat to one’s health could easily drive people to seek testing at the first sign of symptoms they might have ignored in the past. The “scarlet letter” of a positive PCR test could transform a mild cold into a severe disease, possibly leading to deadly outcomes through invasive interventions and toxic treatments. All it takes is the belief that the imaginary threat is real. Once accepted, the mental and physical decline can follow.

“HIV” Discoverer Luc Montagnier understood the power of fear.

While fear over “Covid-19” has subsided in recent years, the mainstream media, with the help of “health” organizations like the CDC and WHO, continue to create a state of constant terror over the next big “threat.” Whether it’s the avian flu, monkeypox, West Nile “virus,” the latest “SARS2” variants, bacterial outbreaks and food recalls, or the mysterious Disease X, there are daily stories alerting the public and keeping the fearful on edge, awaiting the next shoe to drop.

In light of this ongoing fear campaign, I planned to simply post my original article on this topic to ViroLIEgy.com for the Halloween season, hoping to raise awareness. However, the role of the mind in health outcomes is such an important subject—and one I’ve only just begun to explore—that I’ve decided to take a closer look at how fear and its related emotions affected public health during “Covid” to shed more light on this topic. To do so, I’m including an illuminating article from early in the “pandemic” on how fear can spread from person to person faster than an imaginary “coronavirus.” Additionally, I’ve included excerpts from a 2021 study on the psychological consequences of “Covid-19” fear and its impact on underlying illnesses. Together, these papers provide valuable insight into how we were emotionally manipulated during the “pandemic,” and how fear influences health, adding depth and context to the original article.

An interesting, and very prescient, article from the early days of this “pandemic,” published on March 22, 2020, explored how fear can spread from person to person faster than any “virus” could ever hope to do. The author, Jacek Debiec, M.D., Ph.D., an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and an Assistant Research Professor in the Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, stated that a “pandemic of fear” was unfolding alongside the “coronavirus.” Media announcements of mass cancellations, panic shopping, and anti-Asian attacks fueled this spread, especially with the world wide reach and instantaneous nature of modern media. Dr. Debiec noted that “fear contagion spreads faster than the dangerous yet invisible virus,” adding that his clinical and experimental experience had shown him just how powerful fear contagion can be.

Fear Can Spread From Person to Person Faster Than the Coronavirus

But there are ways to slow it down. Here, a neuroscientist explains just how powerful the fear of contagion can be.

As cases of COVID-19 proliferate, there’s a pandemic of fear unfolding alongside the pandemic of the coronavirus.

Media announce mass cancellations of public events “over coronavirus fears.” TV stations show images of “coronavirus panic shopping.” Magazines discuss attacks against Asians sparked by “racist coronavirus fears.”

Due to the global reach and instantaneous nature of modern media, fear contagion spreads faster than the dangerous yet invisible virus. Watching or hearing someone else who’s scared causes you to be frightened, too, without necessarily even knowing what caused the other person’s fear.

As a psychiatrist and researcher studying the brain mechanisms of social regulation of emotions, I frequently see in clinical and experimental settings how powerful fear contagion can be.

Dr. Debiec described fear as a valuable survival function. Using antelopes as an example, he pointed out how one antelope sensing danger can quickly set off an alarm for the rest of the herd by running from a predator. In the blink of an eye, the other antelopes follow suit. This phenomenon is commonly known as “fight, flight, freeze, or fright”—automatic, unconscious behaviors that we share with other animal species.

Responding with fear in face of danger

Fear contagion is an evolutionarily old phenomenon that researchers observe in many animal species. It can serve a valuable survival function.

Imagine a herd of antelopes pasturing in the sunny African savanna. Suddenly, one senses a stalking lion. The antelope momentarily freezes. Then it quickly sets off an alarm call and runs away from the predator. In the blink of an eye, other antelopes follow.

Brains are hardwired to respond to threats in the environment. Sight, smell or sound cues that signal the presence of the predator automatically triggered the first antelope’s survival responses: first immobility, then escape.

The amygdala, a structure buried deep within the side of the head in the brain’s temporal lobe, is key for responding to threats. It receives sensory information and quickly detects stimuli associated with danger.

Then the amygdala forwards the signal to other brain areas, including the hypothalamus and brain stem areas, to further coordinate specific defense responses.

These outcomes are commonly known as fright, freeze, flight or fight. We human beings share these automatic, unconscious behaviors with other animal species.

Dr. Debiec highlighted an important aspect of fear contagion. When the first antelope senses danger, it reacts immediately; the other antelopes, however, don’t detect the threat directly but respond to the fear signal from that first antelope. Similarly, humans are sensitive to fear or panic expressed by those close to us and often respond in kind. This social transmission of fear is especially strong among individuals who are related or within the same group, compared to interactions between strangers. Dr. Debiec further noted that fear contagion serves as an efficient means of spreading defense responses—not only within families or social groups but also across entire species.

Responding with fear, one step removed

That explains the direct fear the antelope felt when sniffing or spotting a lion nearby. But fear contagion goes one step further.

The antelopes’ run for their lives that followed one frightened group member was also automatic. Their escape, however, was not directly initiated by the lion’s attack but by the behavior of their terrified group member: momentarily freezing, sounding the alarm and running away. The group as a whole picked up on the terror of the individual and acted accordingly.

Like other animals, people are also sensitive to panic or fear expressed by our kin. Human beings are exquisitely tuned to detect other people’s survival reactions.

Experimental studies have identified a brain structure called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) as vital for this ability. It surrounds the bundle of fibers that connect the left and right hemisphere of the brain. When you watch another person express fear, your ACC lights up. Studies in animals confirmed that the message about another’s fear travels from the ACC to the amygdala, where the defense responses are set off.

It makes sense why an automatic, unconscious fear contagion would have evolved in social animals. It can help prevent the demise of an entire group bound by kinship, protecting all their shared genes so they can be passed on to future generations.

Indeed, studies show that social transmission of fear is more robust between animals, including humans, that are related or belong to the same group as compared to between strangers.

Nevertheless, fear contagion is an effective way of transmitting defense responses not only between members of the same group or species but also across species. Many animals, through evolution, acquired an ability to recognize alarm calls of other species. For example, bird squawks are known to trigger defense responses in many mammals.

Dr. Debiec explained that fear contagion occurs automatically and unconsciously, making it difficult to control. Once fear is triggered in a crowd, there is often no time or opportunity to verify the source of the terror. This tendency to bypass verification has been apparent throughout this “pandemic,” as many people didn’t question the evidence for a “novel pathogenic virus” themselves. Instead, they relied on the reactions of family and friends, who were influenced by fear-based propaganda. Unlike physical contagion, the terrifying images and information promoted by the media can spread fear effectively without any “virus” being necessary. This fear then travels from person to person, creating widespread panic. As Dr. Debiec noted, while antelopes stop panicking once they’re safely out of danger, the constant stream of alarming images on the news keeps people in a state of fear, so the feeling of immediate danger never subsides.

Transmitting fear in 2020

Fear contagion happens automatically and unconsciously, making it hard to really control.

This phenomenon explains mass panic attacks that can occur during music concerts, sports events or other public gatherings. Once fear is triggered in the crowd – maybe someone thought they heard a gunshot – there is no time or opportunity to verify the sources of terror. People must rely on each other, just like antelopes do. The fear travels from one to the next, infecting each individual as it goes. Everyone starts running for their lives. Too often, these mass panics end up with tragedies.

Fear contagion does not require direct physical contact with others. Media distributing terrifying images and information can very effectively spread fear.

Moreover, while antelopes on the savanna stop running once they’re a safe distance from a predator, scary images on the news can keep you fearful. The feeling of immediate danger never subsides. Fear contagion didn’t evolve under the always-on conditions of Facebook, Twitter and 24-hour news.

Dr. Debiec emphasized that fear contagion, as a social phenomenon, is nearly impossible to prevent once triggered. Actions, he noted, often matter more than words; thus, lockdowns, quarantines, and restrictions became powerful tools for inducing fear. This fear intensified with inconsistent messages that frequently changed based on the shifting “science.” For instance, while people were initially told not to wear face masks, healthcare workers were shown in full hazmat gear. Seeing “authority figures” wear masks against an unseen threat led people to follow suit, buying masks for “protection.”

Although actions are influential, words can be equally powerful in spreading fear contagion. Individuals under stress have a harder time processing details and nuances. When “health” institutions and mainstream media withheld critical facts and continually misled the public, it fostered greater uncertainty, amplifying fear and anxiety.

Tempering fear others transmit to you

There’s no way to prevent fear contagion from kicking into gear – it’s automatic and unconscious, after all – but you can do something to mitigate it. Since it’s a social phenomenon, many rules that govern social behaviors apply.

In addition to information about fear, information about safety can be socially transferred too. Studies have found that being in the presence of a calm and confident person may help overcome fear acquired through observation of others. For instance, a child terrified by a strange animal will calm down if a calm adult is present. This kind of safety modeling is especially effective when you have your eyes on someone close to you, or someone you depend on, such as a caretaker or an authority figure.

Also, actions matter more than words, and words and actions must match. For example, explaining to people that there’s no need for a healthy person to wear a protective face mask and at the same time showing images of presumably healthy COVID-19 screening personnel wearing hazmat suits is counterproductive. People will go and buy face masks because they see authority figures wearing them when confronting invisible danger.

But words do still matter. Information about danger and safety must be provided clearly with straightforward instructions on what to do. When you are under significant stress, it is harder to process details and nuances. Withholding important facts or lying increases uncertainty, and uncertainty augments fears and anxiety.

Evolution hardwired human beings to share threats and fears with others. But it also equipped us with the ability to cope with these threats together.

https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/fear-can-spread-person-person-faster-coronavirus

Dr. Debiec’s article effectively explains how “health” institutions, with support from the pharmaceutically-funded mainstream media, generated enough fear to create the impression of a “pandemic.” This fear contagion spread through a strategic use of visual psychological cues—lockdowns, quarantines, social distancing, masking—paired with powerful fear-inducing headlines and imagery. These elements kept the public constantly updated on the deadly toll the “virus” was allegedly taking locally and globally. Frequent contradictions and shifting information heightened confusion, intensifying fear, anxiety, stress, and depression. Once this fear contagion took hold in China, it spread quickly through an increasingly interconnected world. The “virus” seemed both everywhere and nowhere, leaving people with no sense of escape.

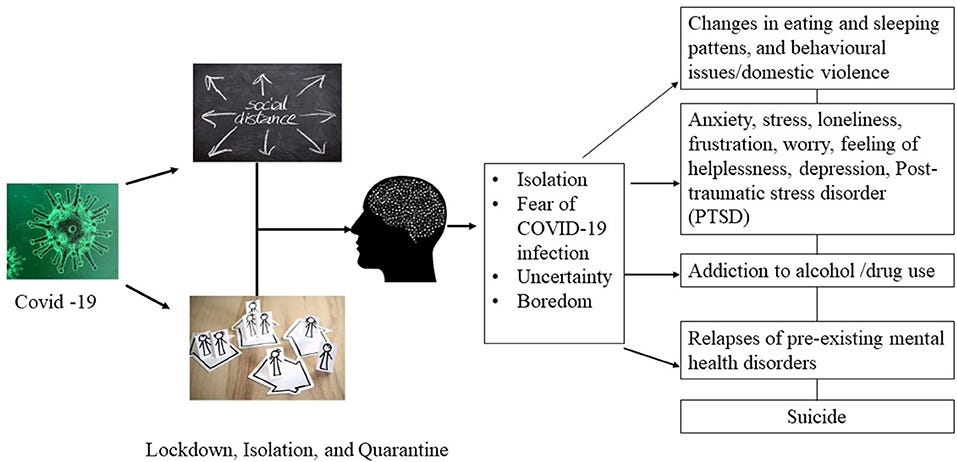

Once the fear contagion was accepted and spread throughout the world, the detrimental effects of the fear generated by an invisible enemy became readily apparent. This was explained in a February 2021 issue of The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, when a group of researchers examined the psychological effects of the fear of acquiring “Covid-19” on specific groups in Turkey. The researchers observed that the rapid spread of the “virus” and the heightened fear surrounding its “threat” contributed to increased levels of depression, stress, and anxiety across different segments of society. Those already in poor health, or who had friends or family affected or lost to illness, experienced even greater psychological impacts.

The study aimed to determine whether the fear of “Covid” was a predictor of stress, anxiety, and depression, and whether individuals with personal or familial illness had heightened psychological issues. Findings revealed that women and young people aged 16–25 exhibited higher levels of “Covid-19-related” fear, anxiety, depression, and stress. Additionally, there was a significant relationship between “Covid-19” fear and stress, anxiety, and depression, with notable moderation effects based on underlying health issues and close connections to individuals affected by the disease.

The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Fear and the Moderator Effects of Individuals’ Underlying Illness and Witnessing Infected Friends and Family

“The COVID-19 virus has become a fearful epidemic for people all over the world. In Turkey, long quarantine periods and curfews have increased both physical and psychological problems. Due to the rapid spread and substantial impact of the COVID-19 virus, different psychological effects were observed among different segments of society, such as among young people, elderly people, and active workers. Because of fear caused by the COVID-19 virus, it is thought that depression, stress, and anxiety levels have increased. It is estimated that there are more psychological issues for people with poor health and others whose friends or family became ill or have died because of COVID-19. To explore and test the situation mentioned above, we conducted a cross-sectional study in Turkey with 3287 participants above 16 years old. We measured COVID-19 fear, along with anxiety, stress, and depression levels (DASS21) and demographics. Firstly, we tested whether COVID-19 fear predicts stress, anxiety, and depression. Secondly, we investigated if the effect of COVID-19 fear is stronger for those who have underlying illness and for those whose friends or family became ill or have died because of COVID-19. The results showed that women and 16–25 years old youths have higher COVID-19-related fear, anxiety, depression, and stress. Furthermore, we found a significant relationship between COVID-19 fear and stress, anxiety, and depression, as well as significant moderation effects of having an underlying illness and having friends or family who were infected or have died. These results show the importance of implementing specific implementations, particularly for vulnerable groups, to minimize the psychological problems that may arise with the pandemic.”

The researchers noted that “pandemics” inflict both psychological and physical trauma on the population, lasting well beyond the immediate crisis. The fear of “Covid-19” triggered various psychological issues, such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances. Additionally, the experiences of social alienation, physical distancing, and quarantine led to increased feelings of isolation and depression. The shift to a “new normal” altered many habits and behaviors, which negatively impacted mental health, compounded by constant uncertainty about when the “pandemic” would end—fueling anxiety and mental distress.

Several risk factors were associated with higher rates of major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorder. These included:

- Having a preexisting mental disorder or chronic physical illness, whether currently treated or previously diagnosed.

- Being diagnosed with “Covid-19,” undergoing treatment, or being quarantined.

- Losing a relative or friend to “Covid-19.”

- A relative or friend contracting “SARS-COV-2.”

- Exposure to intense stress during the period.

- Serious economic loss, job loss, or financial hardship due to the pandemic.

The study’s hypothesis drew from earlier research suggesting that fear of “Covid-19” would have significant psychological consequences. Perceived risks such as illness, “virus transmission,” or death further intensified these impacts. The psychological toll of this fear varied depending on individuals’ health status and whether family members or friends had been “infected” or passed away.

“Societies experience psychological traumas and physical problems both during and after a pandemic [3]. The behavior prompted by the COVID-19 outbreak have resulted in life constraints that we did not believe we would be subjected to before the pandemic [4]. Individuals are not allowed to meet with their friends, and cannot perform daily activities that they used to do before, feeling more isolated than they had before [5]. COVID-19 has triggered multiple psychological issues, including anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances, similar to previous pandemics. Social alienation, physical distance, and quarantines have caused people to feel totally isolated and increased their depression [6]. While the new normal life caused by COVID-19 has changed many of our habits and behaviors, it has also negatively affected our psychology. In addition to the rapidly increasing number of cases in many countries in recent weeks, the uncertainty caused by not knowing when the epidemic will end increases anxiety and has triggered mental problems.

The presence of the risk factors listed below increases the possibility of an individual to be diagnosed with major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and/or anxiety disorder [7]. Those factors are (i) having been diagnosed with a mental disorder or chronic physical illness before the COVID-19 outbreak (treated or still being treated), (ii) being diagnosed with COVID-19, being treated for COVID-19, or being quarantined, (iii) death of a relative or friend from COVID-19, (iv) infection of a relative or friend with the COVID-19 virus, (v) exposure to intense stress during this period, and (vi) serious economic loss, job loss, or bankruptcy caused by the pandemic [7].

The hypothesis of this study is based on a work by Işikli [7], who suggested that there are psychological implications caused by the fear of COVID-19, and that risks such as illness, virus transmission, or virus death will further increase these psychological consequences. Therefore, this study attempted to understand the effects of COVID-19 fear levels on depression, anxiety, and stress levels of people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, moderation analyses were made to measure the effects of COVID-19 fear on depression, anxiety, and stress according to people’s health conditions and their family’s or friends’ infection status. Research has shown that the fear of COVID-19 has a negative impact on people’s psychology. This effect varies according to people’s health condition and whether there are infected or dead among their families and relatives.

The researchers discussed the mental health impact of “Stay at Home” orders, noting that these measures led to negative psychological effects, such as increased depression, health anxiety, financial worries, and loneliness. In fact, all restrictive practices enacted during the “pandemic”—including lockdowns, quarantines, and social distancing—amplified individuals’ fear and anxiety regarding “Covid-19.” The fear generated by the “threat” of the “virus” impaired rational thinking and led to social stigmatization and exclusion. Many people were not only fearful of being “infected” themselves but also worried about “infection” among friends and family. Once the effects of “infection” became widely discussed, a heightened sense of panic and anxiety set in.

Those working in fields like healthcare, teaching, customer service, public transportation, security, and other customer-facing roles reported more intense fear of “Covid-19.” This heightened fear, in turn, increased their levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. For individuals with chronic illnesses or “infected” family members, this compounded fear of “Covid-19” further intensified psychological distress.

COVID-19 Fear of Individuals

In the first weeks, countries did not know how to combat the COVID-19, and the WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on 18 March 2020, after the deaths of 8000 people worldwide [8,9,10,11,12]. The first COVID-19 case was declared by the Ministry of Health in Turkey on 12 March 2020. Although the cases decreased in the summer period, the number of cases increased again in September. As in other European countries, in Turkey, the second wave started in October and November. The number of people infected was more than 2 million and the number of people who died was more than 20,000 as of 20 December 2020 [13].

Schools and universities have remained closed, while working hours in private workplaces, public institutions, restaurants, and entertainment places were restricted. To support reducing the number of infected people, a “Stay at Home” campaign was launched. When the psychological consequences of the call to “Stay at Home” for isolation during the pandemic are examined, it is understood that this practice, critical for protecting physical health, has negative psychological and economic consequences [14,15,16]. Studies have shown that staying at home increases depression, health anxiety, financial concern, and loneliness [16,17,18]. All limitations and practices have further increased the fear and anxiety of individuals for COVID-19.

High levels of infection, asymptomatic cases, and uncertainty are important characteristics of infectious diseases. Therefore, infectious diseases produce more fear than other diseases. Due to the high and rapid transmission rate and unexpected deaths, people have felt increasing fear of COVID-19. This fear, reduces rational thinking and causes individuals to be stigmatized and excluded in the societal arena.

Psychological and social issues such as fear and anxiety have been ignored since infection control, medicine, and vaccination against COVID-19 came to the fore [19]. Initially, COVID-19 was not taken seriously, and after it was known what the infection would cause, a sense of panic and anxiety emerged [20]. Later, it was understood that people feared being infected themselves and feared infection among their friends or family members [21]. It has been found that those who practice healthcare, teaching, customer service, public transport, security, and certain professions with close customer contact feel more fear of COVID-19 [22]. Therefore, it is thought that this extreme fear will increase the depression, anxiety, and stress levels of these individuals [23]. The chronic illnesses of individuals or the presence of infected relatives and family members increase the fear of COVID-19. If the level of fear of COVID-19 increases, it will be difficult for individuals to behave clearly and rationally while responding to both COVID-19 and other events [21].

The researchers highlighted that restrictive actions taken by governments worldwide, combined with the rapid spread of information (or fear propaganda) by mass media, created a global wave of panic, leading to abnormal behavior. Restrictions caused physical discomfort, as people had to stay at home, work remotely, and remain inactive. Constant negative and inconsistent news about the “virus,” consumed primarily by people staying at home through TV, internet, and social media, intensified phobia for many. The fear of “Covid-19” disproportionately affected those not physically or psychologically healthy, leading to worsening psychiatric symptoms that further damaged health (often attributed to the “virus”).

The psychological effects of the “pandemic” may linger for years due to significant negative experiences, such as:

- Inability to fulfill religious and cultural rituals after deaths.

- Job loss leading to increased financial burdens.

- Students being unable to attend school.

- Elderly individuals facing prolonged quarantine and isolation.

- Increased cases of suicide, family and partner violence, and divorce due to heightened psychological stress.

- Rising anxiety due to uncertainty.

The researchers cited several studies illustrating the psychological impact of the “virus” threat across different groups:

- In Spain, an online study by Odriozola-González et al. involving 3,550 adults found 32.4% had high anxiety, 44.1% experienced depression, and 37% reported high stress.

- In China, Wang et al. reported that 16.5% of participants showed moderate to severe depression, 28.8% had moderate to severe anxiety, and 8.1% had moderate to severe stress.

- In a study of 3,524 participants, those aged 18–33 showed more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress than older individuals.

- In France, 24.7% of students had high perceived stress, 16.1% showed depression, and 27.5% reported anxiety.

- Among Chinese adolescents (12–18), 37% had anxiety and 43% had depression, with females representing the highest risk group.

The Effect of COVID-19 Fear on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Due to the quarantines widely applied and the rapid spreading of information by mass media, a global panic wave was created, producing abnormal behavior in humans [24,25]. As several studies showed, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused physical discomfort due to people needing to stay at home for a long time, working from home, and being inactive [26]. Studies show that COVID-19 may cause long-term psycho-social disorders [26,27]. Negative and inconsistent COVID-19 news, mostly watched by people staying at home, on television, the internet, and social media, make individuals even more worried and can cause an increase in COVID-19-related phobia [24,28,29]. In particular, the prohibitions and quarantines applied to deter the accelerated expansion of COVID-19 modify the lifestyles of individuals and increase anxiety, depression, and stress [30]. COVID-19 fear has a greater impact on anxiety, depression, and stress when individuals are not physically and/or psychologically healthy. In addition to that, witnessing family members or friends becoming infected can intensify the negative impact of that fear. Therefore, COVID-19 fear will increase the psychiatric symptoms in an individual, and further the damage the virus will cause to individuals [31].

Turkish people are very sensitive to traditional processes. Funerals have an important place both religiously and traditionally in Turkish society. The psychological effects of the epidemic will last for many years due to certain negative experiences, such as not being able to fulfill religious and cultural rituals after deaths during the pandemic period [16,32]. Additionally, people lost their jobs [15,33], students were not allowed to go to school, the elderly, who were most affected by the virus, are forced to stay in quarantine for a long time, and married couples and their children have experienced problems [6,34,35] by staying at home for long times, resulting in more psychological problems. These psychological problems have increased tensions in both families and society [36]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suicide, family and partner violence, and divorce cases have increased several times in many countries [16,37,38,39,40]. Uncertain questions, such as how long the quarantine will last, will there be difficulties in providing necessities, will schools be reopened, how to use health services in case of COVID-19 virus infection, and how the epidemic will recover the economy, occupy everyone’s minds and increase anxiety [41]. The measures taken for COVID-19 particularly affect the poor, immigrants, refugees, internally displaced people, and vulnerable groups who have to supply their labor daily for their livelihoods [42].

An online study was conducted by Odriozola-González et al. [43] with 3550 adult individuals in Spain, a country with many COVID-19 infections. It was understood that 32.4% of the participants had high levels of anxiety, 44.1% presented with depression and 37% showed high levels of stress [43]. Wang et al. [44] evaluated the pandemic’s psychological effects on individuals in a study with 1210 participants living in different cities of China at the end of January and the beginning of February. They stated that 16.5% of the participants showed moderate to severe symptoms of depression, 28.8% showed moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, and 8.1% showed moderate to severe stress symptoms [44]. In another study conducted with 3524 participants, it was seen that individuals between the ages of 18–33 had more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic; it has been found that older people generally give better psychological responses [45]. A study conducted with students during the COVID-19 period in France found that 24.7% of students had high perceived stress, 16.1% depression, and 27.5% anxiety [46]. In a study conducted on Chinese adolescents (aged 12–18, n = 8079), it was found that 37% of the adolescents had anxiety and 43% had depression, with women being the highest risk group [47]. The Figure 1 illustrates conceptual model and our hypothesis 1 is COVID-19 fear increases (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress.

The researchers referenced a study by Kimter, which found that individuals with strong psychological resilience and healthy lifestyles were less affected by “Covid-19.” In contrast, those with underlying health conditions experienced heightened anxiety and depression when confronted with extraordinary situations, such as a “pandemic” and the “threat” of a “novel virus.” People with family members or relatives diagnosed with “Covid-19” were more likely to experience increased stress, anxiety, and depression, with additional anxiety stemming from the possibility of encountering asymptomatic carriers.

The researchers cited studies indicating that individuals who had been frequently ill prior to the “pandemic” were more susceptible to adverse effects from the symptoms associated with “Covid-19.” They hypothesized that those with ill or deceased friends and relatives labeled as “Covid” cases, as well as those already in poor health, faced greater depression, anxiety, and stress due to their fear of the “virus” and the associated illness.

Moderation Roles of Underling Illness and Having Infected or Dead Relatives and/or Friends

According to the study done by Kimter [48], psychological resilience and being healthy are important individual characteristics in facing the fear of COVID-19 and the psychological problems caused by this fear. Therefore, those people with strong psychological resilience and a healthy life appear to be less affected by COVID-19 [48]. People’s reactions to extraordinary situations may differ if they have an underlying illness, such that those who are sick in extraordinary situations such as a pandemic become more anxious and depressive. With a similar approach, those who have friends or relatives that have been infected with COVID-19 are thought to be more stressed, anxious, and depressive. Encountering or being contacting with infected people who do not show symptoms further increases this anxiety [49,50]. Many studies have found that people who have been sick frequently before COVID-19 are more likely to be adversely affected by COVID-19 [51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Some studies have shown that individuals whose family or friends have become ill or have died because of COVID-19 have more stress, anxiety, and depression [50,58,59,60,61,62]. Therefore, based on aforementioned ideas the hypothesis 2 is that having an infected or dead family member, relative, or friend has a moderation effect on COVID-19 fear, which causes (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress; and hypothesis 3 is that having an underlying illness has a moderation effect on COVID-19 fear, which causes (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress.”

The researchers concluded that all three of their hypotheses on the negative impact of “Covid-19” fear—specifically, increased depression, anxiety, and stress—were supported. Perceived risks, such as having an underlying illness, fear of “virus transmission,” or fear of dying from the “virus,” amplified these psychological consequences, particularly in those with pre-existing health conditions and/or family and friends who were ill or deceased. As a result, the most vulnerable and disadvantaged segments of society were more severely affected than those who were physically and mentally resilient. The lasting impact of the “virus” threat, according to the researchers, is the rise in psychological disorders and physical harm driven by “Covid-19” fear.

Various studies were highlighted, demonstrating that fear of the unknown significantly heightens anxiety among both healthy individuals and those with existing health issues, while also increasing depression and stress. Even the general population experienced significant psychological issues, with many studies showing that “Covid-19” fear pushed levels of depression, anxiety, and stress beyond normal limits.

The researchers emphasized that those who were ill or had loved ones who were ill faced heightened “Covid-19” fear, which worsened their depression, anxiety, and stress levels. The elevated fear levels were attributed to the influence of negative media coverage, quarantine, and curfews. The “pandemic” disrupted mental health, and those with pre-existing illnesses or affected family and friends were psychologically more vulnerable. Additionally, women, young people, singles, and the unemployed were noted as groups particularly impacted by the fear and uncertainty of the situation.

Discussion

“This study was conducted to understand whether fear of COVID-19 has an effect on psychological results such as depression, anxiety, and stress. While analyzing, questions such as the participants’ age, gender, marital status, education level, and health status were used as control variables. All three hypotheses of the study were fully supported. Hypothesis 1, which argues that COVID-19 fear increases (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress, was tested and confirmed in this study. COVID-19 fear was independently associated with those psychological outcomes. Additionally, hypothesis 2, which argues that having an infected or dead family member, relative, or friend has a moderation effect on COVID-19 fear, which causes (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress, was fully confirmed. Hypothesis 3, which argues that having an underlying illness has a moderation effect on COVID-19 fear, which causes (i) depression, (ii) anxiety, and (iii) stress, was accepted. The theory of this study was based on the approach explained by Işikli [7]. According to Işikli, people will confront the psychological consequences of COVID-19 fear, and some risks, such as underlying illness, fear of virus transmission, or fear of dying from the virus, will increase these psychological consequences more.

As predicted, during extraordinary periods such as the pandemic, people change their previous lifestyles, live in more closed areas, are left alone, are affected by negative news, and feel fear and anxiety due to quarantines and curfews [30]. The negative effects of extraordinary situations are felt less by individuals with high psychological strength [48]. Disadvantaged and fragile segments of society are affected much more negatively. Today, COVID-19 has spread worldwide and has damaged societies both physically and psychologically [26,69]. As a kind of disaster, the COVID-19 pandemic, just as previous pandemics, has caused mass deaths and great suffering [20]. Therefore, these problems during the pandemic have negative reflections on both the individual and society. Thus, the long-term damage caused by the COVID-19 virus will be the psychological disorders caused by the COVID-19 fear [31].

In many studies, it has been found that the distress during the pandemic increases the fear of COVID-19, and this rising fear increases depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms of individuals. Fear of the unknown increases anxiety levels in healthy individuals and in those who already have health problems [70]. In Ahorsu’s study on Iranians, it was seen that COVID-19 fear exacerbated psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety [65]. In a study conducted with 1879 individuals in the early stage of the pandemic in the Philippines, the DASS-21 scale was used, and increases in individuals’ depression, anxiety, and stress levels were found [71]. In a literature study, it was found that in addition to the general population experiencing significant psychological problems, depression, anxiety, and stress increased, especially among healthcare workers, students, service sector workers, women, those in quarantine, and those exposed to misinformation [72]. The current study found that COVID-19 fear raises individuals’ depression, anxiety, and stress levels above the accepted level, consistent with many other studies [43,44,45,46,47].

The fear of COVID-19 is expected to increase if individuals are in poor health or have an underlying illness. In this study, it was found that COVID-19 fear increases if individuals are sick or in poor health. It has even been observed that many people who are sick do not go to the hospital for examination due to the fear of COVID-19 infection. Since sick people are more affected by COVID-19, those who are sick have more COVID-19 fear levels [51,52,73]. Similarly, more COVID-19 fear is felt when individuals have relatives or friends who have been infected by or died from COVID-19. Hence, this fear also increases individuals’ states of depression, anxiety, and stress [58,59,61,62]. An interaction effect can be seen from Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, which show the moderation analysis. Hypotheses 2 and 3 of the study were confirmed in this study, which coincides with similar findings in the literature.

During pandemic periods, individuals’ fear of pandemics is extremely high due to people being influenced by negative news, quarantine, and curfews, and experiencing infection or death among their family, relatives, and friends. This study’s theory is that fear of pandemics disrupts people’s psychology and that the psychology of those who had an underlying illness before the pandemic or had family or friends who were infected or had died is much more impaired. This holistic approach has not been seen in the models of other studies before. Therefore, this study shows that it will be beneficial to produce special approaches for those who have the disease before and those most affected by the pandemic among the people affected by COVID-19 fear that emerged during the pandemic. In addition to these groups, it is understood from both the literature and this study that women, young people, singles, and unemployed people are also affected negatively. Due to the lack of sufficient academic studies on this subject in Turkey, this study’s results are expected to be leading for academics and policymakers. In this sense, it is necessary to implement different applications for different groups who are disadvantaged and fragile during the pandemic period.”

The researchers concluded that those in certain situations felt the negative psychological impact of the “Covid-19 outbreak” more intensely, with psychological consequences that could prolong or exacerbate physical effects. While physical symptoms may gradually improve, these psychological impacts are predicted to be long-lasting without intervention.

Conclusions

This study provides preliminary evidence that the negative psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak affects those in certain situations more. In particular, current results should be taken into account when developing evidence-based policies and practices. With this study, it was understood that the pandemic had not only physical consequences but also psychological consequences. In fact, these psychological consequences are predicted to be long-term, unless action is taken. This preliminary work provides academicians and policymakers a glimpse of what may happen in a pandemic, and which parts of societies are the most affected and vulnerable. Moreover, in the case of the pandemic, this study shows what kind of strategies can be implemented in the years to come to those who are negatively affected by the psychological consequences of pandemic fear in Turkey. These practices should include an approach in the form of support strategies specific to each group.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7917729/

The 2021 study doesn’t present groundbreaking revelations; it’s clear that fear, as a powerful emotion, naturally leads to heightened anxiety, depression, and stress when facing an uncertain “threat.” However, the study does underscore key factors contributing to this amplified fear, such as the relentless, often contradictory news about the “virus” spread across TV, the internet, and social media, along with restrictive government actions world wide. The combination of these restrictions and the mass media’s rapid dissemination of fear-induced messaging drove up fear, anxiety, depression, and stress across all demographics, with particularly severe effects on those with preexisting health conditions and those with loved ones who were unwell. No actual “virus” was necessary to destabilize mental and physical health; only the threat of an invisible “virus” and the fear it generated sufficed.

In my original article on this topic, I highlighted how the health effects from heightened fear and related emotions closely mirror those attributed to “Covid.” It only takes a fear signal from an initial group to alert the rest, allowing the fear virus to spread rapidly across a vulnerable population. Once triggered, it no longer matters whether the threat is real or fictional; the mere mental perception is powerful enough to achieve the intended outcome. This effect is especially strong among the most mentally and physically susceptible, thereby increasing case numbers and reinforcing the perceived “threat.”

What began in early 2020 was a sophisticated psychological operation targeting the all of humanity, building on decades of groundwork laid by previous events like AIDS, SARS, and Swine flu. All that was needed was the foundational beLIEf in “pathogenic viruses” capable of triggering a “pandemic” to allow this fear virus to take hold, exacting a heavy physical and emotional toll on its host. The fear virus then spreads person to person in a cyclical trap, one that can only be broken when those infected understand the pseudoscientific fraud that has been perpetrated on a massive scale.

0 Comments