Forsaking Cahokia: Five Lessons From The Collapse of a Native American Empire

by Justin McAffee | Jul 20, 2025

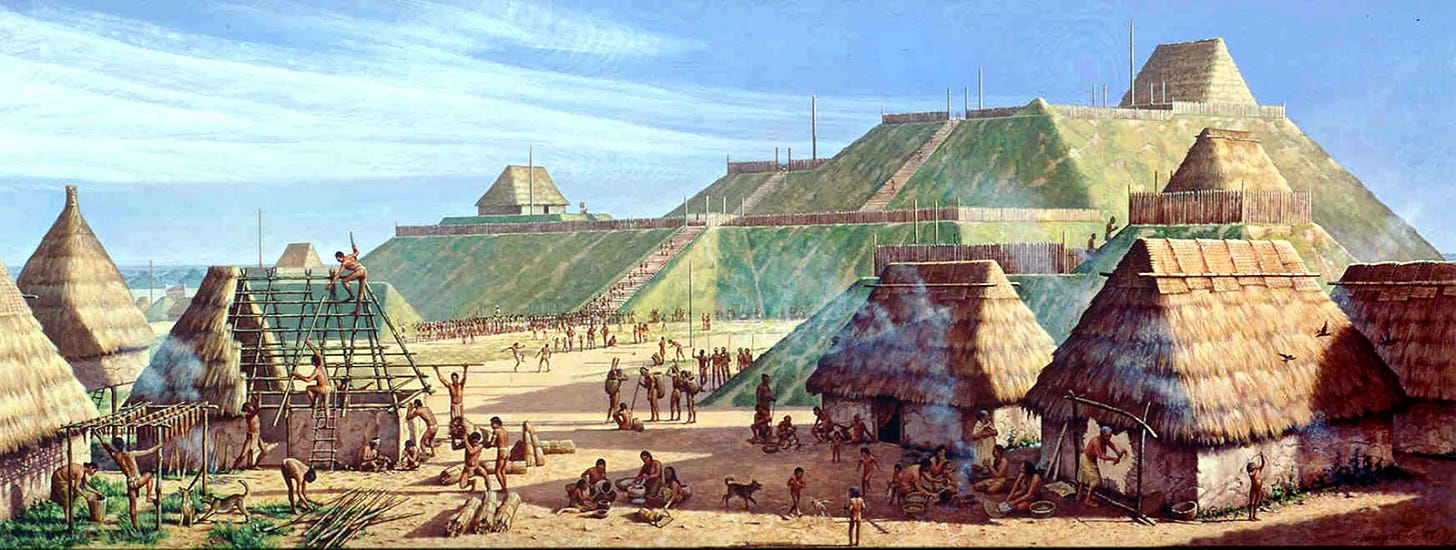

Before Manhattan or St Louis, before Washington D.C., there was a sprawling city built of earth and sweat near the banks of the Mississippi River called Cahokia. By A.D. 1100, it was the largest urban center north of Mesoamerica, with a population estimated between 10,000 and 20,000, possibly more when including outlying areas. Dominated by massive earthen mounds, some larger at the base than the Great Pyramid of Giza, Cahokia was North America’s only major pre-Columbian urban complex within what is now the continental United States. No other indigenous city matched its scale, density, or political complexity before European contact. It was the apex of Mississippian civilization. Then, within a few generations, it was gone.

I grew up near Cahokia and other mound places like Kincaid and Cleiman in Southern Illinois. I always wondered what happened to the people who built those strange grass-covered mounds. I decided recently that I should find out what this and other questions could be answered with research today. I found a journal on collapse from my old stomping grounds, Southern Illinois University.¹ Here’s what I found.

Lesson One: We Can Walk Away From Civilization.

People sometimes tell me our society is too complex to ever simplify. People won’t go for it they say. Cahokia’s story turns that argument on its head. At its peak, Cahokia had all the trappings of what we’ve come to associate with “civilization”: rigid class divisions, elite-controlled ritual sites, organized labor, massive infrastructure projects, and a web of influence stretching across much of the continent. It was a true city, in the planned, monumental, and ideologically saturated sense.

But then, it unraveled. Slowly, not all at once. People stopped building the mounds. The centralized rituals faded. The population declined. And rather than descend into chaos, mass starvation, or endless war, people left. They dispersed into smaller, decentralized communities. They returned to the margins, to the forests, the rivers, the borderlands. And crucially, they didn’t rebuild.

People often characterize collapse as failure. But as Joseph Tainter points out, that is a perspective based on cultural bias. It’s a normative judgment. In the case of Cahokia, it was a strategic choice and cultural refusal. A conscious abandonment of complexity that had grown brittle and burdensome. No civilizational successor arose to reclaim or reoccupy the mounds. No dynasty tried to restore the old order. Instead, post-Cahokia societies reorganized around egalitarian lifeways, regional autonomy, and ecological sustainability that also included agriculture.

That’s not really collapse. Contemporary anthropologists suggest this collapse is better viewed as a transformation.

So as we contemplate our own era’s mounting instability, we would do well to remember civilization is not a one-way street. It’s a construct, not a destiny. And when its logic no longer serves life, it can be walked away from. Just as it was before.

Lesson Two: Complexity Is Fragile, Not Sacred

The dominant culture equates complexity with progress. It believes that the more intricate the system (politically, technologically, and economically), the more “advanced” a society becomes. But Cahokia dismantles that illusion.

At its height, Cahokia was a marvel of complex coordination. Monumental architecture required thousands of workers moving earth by hand. Ceremonial calendars demanded astronomical precision. Elite authority was maintained through ideological spectacle, labor control, and possibly coercion. The city’s very existence depended on the delicate synchronization of food production, trade, spiritual unity, and environmental stability.

Complexity became a trap in Cahokia. It demanded more labor, more control, more ideology to sustain itself. Rigid control is never good for adaptation. When the environment shifted or faith in the ruling class eroded, there was no graceful fallback. The pyramid scheme of power and prestige could not tolerate disruption.

Today, we live in systems just as complex, and even more brittle. Global supply chains, complex market systems, algorithms, and neoliberal governance. They have only made us more dependent on them, more rigid, less adaptable. When they falter, so will most people, like a house of cards.

Cahokia is a reminder from the past that complexity is not sacred. It is not inherently desirable. It can become a burden, a vulnerability. And when it does, the most intelligent response might not be to rebuild, but to walk away.

Lesson Three: Civilization Is So Bad, Native People Erased It From Memory

After Cahokia fell, the silence was thunderous.

Unlike the ruins of Rome, where successors fought to claim imperial lineage, or Egypt, where dynasties kept the memory of pharaohs alive through millennia, Cahokia left no epic, no myth, no trace of cultural nostalgia. The people who came after did not honor the mounds as sacred relics of a lost golden age. They did not mythologize their ancestors’ empire. They simply left it behind.

When 19th-century Europeans asked local Native peoples about the mounds, the answers were consistently vague: “We don’t know who built them.” No tribal memory, no songs or stories clearly preserved Cahokia’s legacy. In the most profound sense, it was forgotten.

The people who outlived Cahokia remembered just how awful their brief experiment with civilization was. They remembered the inequality, the ritual violence, the food stockpiles controlled by elites, the pressure of centralized power. And rather than preserve those memories as heritage, they chose to bury them in silence. In that way, forgetting became a revolutionary act. A refusal to keep the story of hierarchy alive. That’s how bad it was.

In the aftermath, no one rebuilt the city. No monuments were raised in remembrance. Instead, people lived in small villages, practiced subsistence farming, and kept the mounds at their backs unworshipped and unreclaimed.

Lesson Four: You Can Have Agriculture Without Civilization

One of the great myths of civilization is that agriculture and urbanization are inseparable. And there’s truth to that. Often, as it goes, people learn to farm, then cities, hierarchies, and states inevitably follow. Cahokia’s rise seems to affirm this. Its meteoric growth was fueled by a surplus of maize, stored and distributed under elite control. The assumption is that to feed people efficiently, you must centralize power.

But the history after Cahokia tells a different story.

When the city declined, agriculture didn’t vanish with it. People kept farming. They grew maize and other staples in smaller communities, without monumental mounds, without priests or kings, and without armies to guard granaries. They shifted from surplus-driven economies to subsistence-level production.

Today, amid global ecological collapse and industrial food system failures, this lesson is more urgent than ever. We don’t need bigger machines or more centralized logistics. We need resilient, localized, decomplexified systems. Gardens, not factories. Fields tended by communities, not corporations.

Lesson Five: There’s No Diversity Without Equity and Inclusion

Cahokia was a convergence of people who came from hundreds of miles away: the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the Appalachian foothills. They brought different languages, customs, and beliefs. Archaeological evidence like pottery styles, burial practices, isotopic markers, confirms this was a cosmopolitan center, likely the most ethnically diverse city in pre-Columbian North America.

This diversity was part of Cahokia’s early vitality. It drew talent, labor, spiritual energy. Diversity gave the city scale, scope, and a unifying myth of shared purpose under elite rule. But over time, the very thing that made Cahokia powerful also made it vulnerable.

As central authority weakened, diverse populations fragmented. Without a shared language of governance or an egalitarian social fabric, ethnic divisions may have deepened. Cohesion unraveled. What was once a unifying force became a source of disintegration.

The lesson we learn from Cahokia is that diversity without shared power, without meaningful inclusion, breeds resentment and instability. When it’s managed from above rather than nurtured from below, it fractures rather than fortifies.

Modern parallels are glaring. The United States, too, is built on diversity, and often mismanages it through coercion, assimilation, and top-down identity politics. Like Cahokia, we risk letting diversity become a stressor rather than a strength, if we don’t pair it with equity and decentralized, participatory governance. We all have to decide how to run our lives. Not 30-40% of voters, or 1% if you really get down to brass tacks. The present system will only falter more as it tries to restrict inclusion and participation further.

Conclusion: How to End a Civilization

Civilization is not held together by bricks or laws or armies. It’s held together by belief. The mounds of Cahokia stood because people believed they mattered. The rituals continued because people showed up. The elites ruled because others accepted their rule. When the myths that justified hierarchy and ritual and control no longer made sense, the whole structure unraveled.

There was no dramatic overthrow. No apocalyptic war. People simply withdrew their consent. They stopped building. They stopped participating. They walked away into smaller villages, the forest, on the land.

This is the deepest lesson Cahokia offers us: the only real power empire has is our compliance. Without our labor, our faith, our participation, the machinery stalls. The myths collapse. The empire withers.

Yes, we live in a different age where we are digitally surveilled, militarized, owned by data and debt. We can’t walk away in the same way. But we can still refuse. Refuse the lies of endless growth. Refuse the rituals of consumption. Refuse to be governed by systems that commodify life and extract from the living world.

What if collapse isn’t something that happens to us, but something we begin, intentionally, by refusing to uphold the myths that keep the empire standing? Then we could call it transformation.

We are left with one simple conclusion. While resistance may require confrontation, risk, and sharp tactics, the most revolutionary and final act will be when we walk away.

Subscribe to Collapse Curriculum

Notes:

¹ Pauketat, Timothy R. “Historical and Ritual Landscapes of Cahokia.” In Beyond Collapse: Archaeological Perspectives on Resilience, Revitalization, and Transformation in Complex Societies, edited by Ronald K. Faulseit, 221–236. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016.

0 Comments