From land grabbers to carbon cowboys: a new scramble for community lands takes off

by GRAIN | Sep 17, 2024

In a recent interview with the New York Times, billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates was asked if there were types of projects that he would not invest in to offset his greenhouse gas emissions.

“I don’t plant trees,” he replied, adding that planting trees to deal with the climate crisis was complete nonsense. “I mean, are we the science people, or are we the idiots? Which one do we want to be?”[1]

Microsoft, the company he built his fortune on and, according to insiders, still actively advises, sees it differently. In June 2024, the tech giant bought 8 million carbon credits from the Timberland Investment Group (TIG), a fund owned by the Brazilian agribusiness lender BTG Pactual.[2] TIG is raising US$1 billion to buy and convert pasture lands to large-scale eucalyptus plantations across the Southern Cone of Latin America.[3] As these trees grow, they draw carbon from the atmosphere and store it in their roots, trunks and branches. TIG will estimate the amount of carbon removed and then sell it as carbon credits to Microsoft and other corporations.

Each carbon credit that Microsoft buys from TIG is supposed to offset one tonne of the emissions Microsoft generates burning fossil fuels. This is one of the main ways that Microsoft and many other companies are planning on getting to “net zero” emissions, while still burning fossil fuels.

Microsoft’s deal with TIG, reportedly the largest “carbon dioxide removal credit transaction” in history, is just one of many investments Microsoft is making in tree plantations as a way to offset its emissions.[4]

The Dutch agribusiness lender Rabobank is another source of carbon credits for the tech company. It too is acquiring land in Brazil for tree plantations, in this instance with a local agribusiness family with a track record of illegal deforestation and fraud.[5] But most of the carbon credits Rabobank sells to Microsoft are from its programme to plant trees on the lands of small coffee and cacao growers in Latin America, Africa and Asia. This programme, called Acorn, uses satellites and a Microsoft digital platform to measure the number and size of shade trees that small farmers plant on their farms and then calculate the carbon they’ve removed from the atmosphere. It then sells the carbon to Microsoft as “carbon credits” for about US$38 a piece, taking a 20% cut for itself and its local partner, and paying farmers what’s left of the proceeds.[6]

A big problem with Rabobank’s scheme, identified in an investigation of its project with cacao farmers in Côte d’Ivoire, is that it is vastly overestimating the carbon removed — in this case by 600%![7] What’s more, the Côte d’Ivoire government says Rabobank is likely double dipping as its project overlaps with a World Bank-funded scheme that has already generated and sold carbon credits from trees planted on small cacao farms in the same area.

All of this “nonsense”, as Gates calls it, has not stopped an increasing number of corporations, governments and billionaires — not to mention a new industry of climate consultants and carbon brokers — from promoting the idea that emissions from fossil fuels can and should be offset by planting trees or other crops that sequester carbon.

Such projects have a chequered history that goes back to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, but they really only took off after the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement, when governments endorsed the notion of offsets and carbon markets as an effective means to get corporations to cut their emissions.[8] Today, most offset projects are in the so-called “voluntary market”, where private companies from the global North manage the certification and sale of carbon credits to corporations that want to show they are taking action to deal with climate change. The projects, largely in the global South, can be for anything from the distribution of clean cook stoves in Malawi to the preservation of rainforests in Indonesia. The premise is that the project either prevents emissions that would have occurred without it, or that it leads to the removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. Cook stoves and rainforest preservation are examples of emissions avoidance. Planting trees, on the other hand, is the most popular form of removal.

In a 2024 study, the World Rainforest Movement (WRM) says that the number of tree planting projects for carbon credits has tripled over the past three years.[9] WRM says the surge is partly driven by the large number of high-profile scandals in emissions avoidance schemes, known as “REDD+”.[10] Numerous projects to preserve forests have been withdrawn or suspended from carbon markets after investigations showed they were based on implausible stories about the threat of deforestation or that they caused human rights violations and other harms to local communities. As a result, WRM says corporations are turning their attention to tree planting as a source of “high-integrity” carbon credits. This is now spawning a mad rush to secure lands where trees can be planted.

The carbon farmland grab

Activists and scientists have been warning for years that schemes to offset carbon emissions by planting trees or other crops would lead to a surge in land grabbing, especially in the global South.[11] These warnings are now proving true.

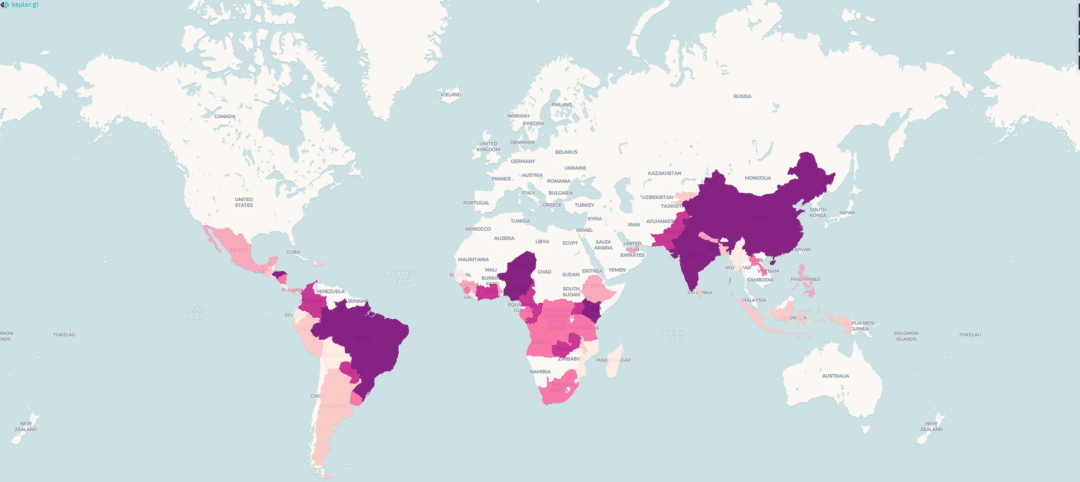

GRAIN combed through the various registries of carbon offset projects to try and get a better sense of this new land grab and how it is unfolding. We identified 279 large-scale tree and crop planting projects for carbon credits that corporations have initiated since 2016 in the global South. They cover over 9.1 million hectares of land — an area roughly the size of Portugal. (See Box 1: What’s included and what’s not included in the land deal dataset)

The deals (view the dataset below) add up to a massive new form of land grabbing that will only increase conflicts and pressures over land that are still simmering from the last global land grab spree that erupted in 2007-8 in the wake of global food and financial crises. They also signify that new sources of money are now flowing into the coffers of companies specialised in taking lands from communities in the South to enrich and serve corporations, mainly in the North.

Compiled by GRAIN. Technical development by the UChicago Data Science Institute, with support from the 11th Hour Project

Box 1: What's included and what's not included in the land deal dataset:

What’s in?

Our data covers projects from all the major voluntary offset project registries. These are: American Carbon Registry (ACR), Climate Action Reserve (CAR), Gold Standard (GS), Verra (VCS), BioCarbono (BC), Cercarbono (CV) and Plan Vivo (PV). It also includes cases on the website farmlandgrab.org that are not yet found in the registries.

The projects in our dataset are limited to projects that:

- involve the large-scale planting of crops and/or tree species on a combined area of land over 100 ha for the purpose of producing carbon credits;

- are driven by companies from outside the communities;

- are located in the global South.

The projects involve either 1) the creation of large-scale plantations or 2) contract production with small farmers. But all the projects bind the use of the land to the terms of the project for 20 years or more.

What’s not in?

REDD+ projects, which aim to avoid deforestation, are not included. Some types of projects that produce carbon credits through tree planting or agriculture on large areas of land are not included either. These are:

- projects to manage pasture lands, which affect the access to lands and traditional practices of pastoralists;

- projects to restore or create mangroves, where large areas of coastline are taken over for the planting of mangrove trees; and,

These projects are extremely important and can have equally severe impacts on communities, including land grabbing, but they are not covered here to keep the dataset manageable.[12] Our data also does not cover projects located in the global North, such as in New Zealand, Scotland and Australia, where national schemes that endorse tree planting for carbon offsets have led to a displacement in food production and undermined farmers’ access to land.[13]

To date, 52 countries in the global South have been targeted by these projects. Half the projects are in just four countries: China, India, Brazil and Colombia, which are developing their own industries of carbon project developers. But projects in these countries account for less than a third of the total land area involved. The most affected region, in terms of land area, is Africa, with projects covering over 5.2 million hectares.[14]

Many of the projects involve land deals to set up giant eucalyptus, acacia or bamboo plantations. Typically, these are pasture lands or savannahs that were used until now by local communities for grazing livestock or growing food.

An even larger number of projects are implemented on small farms. Typically, in these cases, farmers must show proof that they have title over the lands and are asked to sign contracts in which they commit to plant and maintain a number of trees on a portion of their land. According to these contracts, farmers transfer the rights to the carbon in the trees and in the soil to the project proponents. While these deals do not displace farmers from their lands, they are a form of contract production. Farmers are effectively ceding control over a portion of their lands to an outside company for decades. They can no longer do what they want on the land. The projects can also encourage, and in some cases directly facilitate, a shift from collective forms of land management to privatised, individual property. (See Box 2: Carbon colonialism)

The money that investors plan to capture from these deals is immense. The projects we pulled from the Verra and Gold Standard registries alone will generate 2.5 billion carbon credits (1 credit = 1 tonne of CO2 removed) over their lifetime. With an average price of about US$10 per credit, that adds up to a potential bounty of US$25 billion.[15]

Here come the “idiots”

While these projects are exclusively set up in rural areas with extremely low emissions per capita, it is quite the opposite when it comes to the companies orchestrating the projects. With the exception of what’s happening in India and China, most carbon projects are led by foreign companies in rich countries with atrocious emissions records — such as the Netherlands, the US, Singapore, Switzerland, the UK, France, Germany and the UAE.[16] There is a clear colonial dynamic at work, with companies and big NGOs from the North once again using the lands of communities in the global South for their own agendas and their own benefit.

A good number of actors driving this new wave of land grabs are in fact repeat offenders from the global farmland grab that took off a decade and a half ago. This is especially the case in Africa. (See Box 3: Africa’s land grabbers are back in business) There are also several companies from the forestry sector with histories of land grabbing and conflicts with local communities. Much of the vast eucalyptus plantations of Brazilian paper giant Suzano, for example, which is involved in three large-scale carbon plantation projects, have been grabbed from Brazil’s indigenous and traditional peoples.[17] And a non-negligible number of project developers have records of illegal dealings and financial scandal. They include:

- Ricardo Stoppe Jr, Brazil’s “carbon king”, who was arrested in June 2024 for running an illegal carbon credit sale and land grabbing scheme;[18]

- Martin Vorderwulbecke, a German businessman with a neem tree carbon project in Paraguay, who is accused of defrauding Slovenia’s national airline of millions of dollars;[19]

- Alexis Ludwig Leroy, a French/Swiss carbon trader developing tree planting projects in Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of Congo, who is reportedly under investigation for money laundering and financial connections to Colombia’s “queen of cocaine”;[20]

- Vittorio Medioli, an Italian/Brazilian businessman and politician with a carbon tree plantation in Brazil, who was convicted in Brazilian courts for currency evasion and sued for cartel and gang formation in the transport sector;[21] and,

- Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al Maktoum, a member of the UAE royal family seeking tens of millions of hectares in Africa for carbon offset projects, who is accused of overcharging Ghana on the supply of Russian-made Covid vaccines and who is advised on his African carbon deals by an Italian businessman convicted for a bankruptcy fraud that sank one of Italy’s largest telecommunications companies.[22]

The money being hustled by these carbon cowboys comes mainly from the world’s most polluting corporations, who are interested in buying carbon credits to greenwash their emissions. At the top of the list of credit buyers are fossil fuel companies (See Box 4: Tree planting for oil pumping). But there are also tech giants like Meta and Apple, food companies like Danone and Coca-Cola, and supermarket chains like Mercado Libre and Carrefour. Amazon and the philanthropic arms of its billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, are heavily involved, too. Bezos both buys credits and funds the NGOs and companies running the plantations, through initiatives like the AFR100 fund, which aims to plant trees on 100 million hectares in Africa.[23] The same goes for development banks, like FMO of the Netherlands, the US International Development Finance Corporation or the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, which provide cheap loans, political risk insurance and even equity investments to many carbon plantation companies.

Box 2: Carbon colonialism

On 15 April 2022, a group of about 150 farmers gathered outside the operations of Belgian supermarket Colruyt. Standing behind wheel barrows of soil, the farmers accused the company of “stealing lands” by buying up hundreds of hectares of the country’s scarce farmland, ironically as part of a campaign to buy local. “Each piece of land that Colruyt buys is a piece of land taken away from Belgian family farms,” they said.[24]

Far away, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the supermarket chain is also acquiring land, but for decidedly not “local” reasons. In 2021, Colruyt got a 25-year, 10,656 ha concession in Kwango province — about 50 times the size of its Belgian farmlands. It plans to establish tree plantations to offset its emissions on these lands, which are currently used by local people for food crops, and to hire security guards to protect the trees from villagers and their “slash and burn” agriculture.[25]

In neighbouring Uganda, the Swedish hamburger chain Max is also buying credits from a carbon plantation project, but with a different approach. Rather than displacing local farmers, it gets them to plant trees on their own lands. Participating farmers sign a contract stating that they will plant and maintain trees, get seedlings and a little training, and submit to periodic checks. In return, they get payments for the carbon credits bought by Max to offset its hamburgers.

But when a team of journalists from the Swedish media site Aftonbladet visited the farmers in early 2024 they found a horror show.[26] The farmers said they had planted the trees as they were told, not knowing that these trees were offsetting a corporation’s pollution. Things started off fine, but the trees are fast growing and quickly started taking over their fields, sucking up all the sunlight, nutrients and water. The US$100 a year in payments from carbon credits did not cover the loss of food and income from their crops. Eight years into the project, the Swedish media crew found farmers starving — and some were chopping down the trees despite threats of prison for breach of contract by the project proponent.

“I used to be something called a model farmer,” says Samuel Byarugaba, one of the farmers. “People came to me to learn about farming and I was proud to show our farm. We had enough food to feed ourselves and could sell the surplus. Now it’s all disappeared.”

Corporations from the financial sector are also starting to get involved — a worrying sign that much more money could be mobilised. Rabobank and BTG Pactual are leading examples of financial players establishing specialised funds to invest in carbon plantations on behalf of pension funds, billionaires, sovereign wealth funds, university endowments, development banks and other institutional investors. Their investment in carbon plantations dovetails with the landholdings that many of these actors have already amassed through timber and farm land investments.[27]

The Renewable Resources Group, for instance, is a US private equity firm whose investors include Goldman Sachs and the Harvard University endowment. It specialises in “monetising” water by buying up land in parts of the world where it can get access to cheap irrigation to produce high value crops for export, like grapes and berries. It has already acquired over 100,000 ha of agricultural lands in parts of Mexico, the US, Chile and Argentina where there are water scarcity issues.[28] Recently it established a “nature-based solutions” division through which it acquired the German-based private equity fund 12Tree. Since 2017, 12Tree has acquired 20,000 ha in Latin America and Africa to establish “regenerative” farms where it plants trees and generates carbon credits.[29]

Certified scams

One big difference between earlier land grabs for food production and today’s land grab for carbon offsets is that the carbon deals are “certified”. Verra and Gold Standard, two of the top certifiers, are paid large sums of money to ensure that offset projects are done in consultation with local communities, avoid displacing them and even provide them with some benefits. It’s the kind of system that agencies like the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation and the World Bank have long claimed would solve the ills of the global farmland grab.

Yet, our dataset and the growing number of investigations by academics, media and civil society into projects certified by these companies put the lie to such claims.[30] How could anyone expect that a market premised on acquiring lands from rural and indigenous communities in the global South, for the benefit of corporations in the global North, could amount to anything other than a massive land grab? No benefit-sharing mechanism, often baked into these carbon deals, alters that outcome.

Box 3: Africa's land grabbers are back in business

The rush for land that followed the food and financial crises of 2007-8 hit Africa hard. Hundreds of communities were displaced from their lands to make way for large-scale industrial farms. Yet, even though many of these farms failed badly, the communities are still struggling to get back their lands.[31] Some culprits in that land rush (and near cousins) are now trying to get lands for carbon plantations. Below are some examples.

Gagan Gupta: As President of agribusiness giant Olam International, this Singaporean businessman oversaw the company’s 300,000 ha land deal in Gabon in 2011 to build Africa’s largest oil palm plantation. The operation has been mired in conflicts with communities ever since. Now Gupta is running a UAE-based tree plantation company, Sequoia Plantation, which is in the process of securing 200,000 ha in Togo, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo for large-scale tree plantations with carbon offset components, despite protests from affected communities.[32]

Kevin Godlington: This UK businessman orchestrated several failed large-scale land deals in Sierra Leone. One was an oil palm plantation in the District of Port Loko that cleared forest and displaced people from their lands before it went bankrupt. Undeterred, Godlington is now going after the same lands with a new venture listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange that claims to have lease rights to 57,000 ha to plant trees for carbon credits, some of which have already been bought by British Petroleum. As with the first round of land deals, no matter how things pan out, Godlington has already pocketed millions of dollars from the scheme.[33]

Kevin Godlington: This UK businessman orchestrated several failed large-scale land deals in Sierra Leone. One was an oil palm plantation in the District of Port Loko that cleared forest and displaced people from their lands before it went bankrupt. Undeterred, Godlington is now going after the same lands with a new venture listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange that claims to have lease rights to 57,000 ha to plant trees for carbon credits, some of which have already been bought by British Petroleum. As with the first round of land deals, no matter how things pan out, Godlington has already pocketed millions of dollars from the scheme.[33]

Carter Coleman: This UK businessman built the infamous Kilombero Plantation Limited rice farm on 5,818 ha of contested community lands in the heart of Tanzania’s Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor. Despite heavy backing from foreign development banks and investors, it went bankrupt in 2019. Coleman is now back with a new company called Udzungwa Corridor Limited that will generate carbon credits by planting “rare tropical hardwoods” on a 7,500 ha stretch of land leased from local farmers along the Kilombero Nature Reserve.[34]

Andrea Tozzi: This Italian businessman, CEO of his family’s company Tozzi Green, acquired 11,000 ha of land in the Ambatolahy commune in the Ihorombe region of Madagascar in 2012 and 2018 to grow the biofuel crop jatropha. That project failed, and the company switched to growing maize for animal feed and essential oil crops. All the while the communities have been fighting to get their lands back, which they say they need to graze their cattle and grow food for their families. Tozzi is now trying to save his project by replacing the maize with plantations of acacia and eucalyptus for carbon credits — which communities are still firmly resisting.[35]

Andrea Tozzi: This Italian businessman, CEO of his family’s company Tozzi Green, acquired 11,000 ha of land in the Ambatolahy commune in the Ihorombe region of Madagascar in 2012 and 2018 to grow the biofuel crop jatropha. That project failed, and the company switched to growing maize for animal feed and essential oil crops. All the while the communities have been fighting to get their lands back, which they say they need to graze their cattle and grow food for their families. Tozzi is now trying to save his project by replacing the maize with plantations of acacia and eucalyptus for carbon credits — which communities are still firmly resisting.[35]

Karl Kirchmayer: This Austrian businessman, who spent years buying up 147,000 ha of farmlands in Eastern Europe, now has an African land grab venture, ASC Impact. It is partnering with a Senior Advisor to the President of Uganda and a Dubai businessman close to the royal family to sell 60 million tons of carbon credits to UAE companies from mangrove and tree plantation projects, mainly in Africa. ASC Impact is currently negotiating for 27,000 ha in Ethiopia, 25,000 in Angola and 270,000 in the Republic of the Congo!

Frank Timis: This Romanian-Swiss businessman is the founder and majority shareholder of African Agriculture Holdings Inc, a US company listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange, that took over 25,000 ha of lands from a failed Italian company that local communities in Senegal have been fighting to get back for over a decade. His company is also responsible for the largest land deal in our database — a ridiculous pair of 49-year leases covering 2.2 million ha in Niger, where the company will produce carbon credits by planting pine trees.

Frank Timis: This Romanian-Swiss businessman is the founder and majority shareholder of African Agriculture Holdings Inc, a US company listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange, that took over 25,000 ha of lands from a failed Italian company that local communities in Senegal have been fighting to get back for over a decade. His company is also responsible for the largest land deal in our database — a ridiculous pair of 49-year leases covering 2.2 million ha in Niger, where the company will produce carbon credits by planting pine trees.

And while nine million hectares is already too much, things could get much worse. The UN climate negotiations are moving towards establishing an international carbon trading mechanism that would allow heavy polluting country governments and their companies to offset national emissions through deals for carbon projects in other countries, mainly in the global South.[36] If and when this happens, the value of carbon credits could surge, generating even higher demand for land to plant trees. Pressure is also coming from efforts to establish markets for biodiversity offsets, which will trigger a feeding frenzy among investors eager to make a buck from the territories of small farmers, indigenous peoples and pastoralists.[37]

The idea that planting trees or other means of generating carbon credits can compensate for fossil fuels emissions is a dangerous distraction, incompatible with the real cuts to emissions that are required to deal with the climate crisis.[38] Consider, for instance, that even if the dubious emission removal estimates of the 279 projects in our dataset were true, they would only amount to 55 million tonnes of CO2 per year– not nearly enough to even cover last year’s 90 million tonne increase in global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels.[39]

Social movements and organisations need to be relentless in exposing these contradictions, harms and frauds. We also need to get more information to the communities on the ground. They are often confused by what the project proponents tell them and not exposed about what other communities have experienced. They are almost never informed about how the projects are designed to enable big corporations to keep polluting and how this pollution is connected to the terrible impacts they are suffering from climate change. The hype about the money to be made, under the misnomer of benefit sharing, can create divisions within communities and draw some families into signing contracts they may soon regret. As all these carbon projects are premised on formal land ownership, they can also undermine community systems of land management.

There are already cases where communities have faced violence and intimidation for resisting carbon offset projects and this is only going to escalate. It is therefore becoming increasingly urgent to share information and experiences about the carbon grabs – locally, nationally, regionally and internationally — so we can put a stop to them. The double threat to communities – both from climate change itself and from these criminal solutions to it — should not be allowed to play out.

Box 4: Tree planting for oil pumping

In September 2023, the oil company Shell shocked carbon markets when it abruptly cancelled plans to plant trees on 12 million hectares of land by 2030 – an area three times the size of its home country, the Netherlands.[40] There wasn’t much to celebrate, however, as the company also scrapped plans to reduce oil production.[41] It’s not clear if Shell was backing out entirely from the carbon offset industry, either. Shell still owns a controlling stake in a Dutch biodiesel company seeking to generate carbon credits by planting pongamia on 120,000 ha in Paraguay.

Shell’s European cohorts have not yet lost their enthusiasm for carbon plantations. Italy’s Eni has a biofuel venture pursuing carbon credits in Kenya contracting farmers to grow croton plants on an initial 40,000 ha. British Petroleum (BP) paid Canada’s Carbon Done Right US$2.5 million earlier this year for carbon credits from a 57,000 ha tree plantation project the company is pursuing in Sierra Leone. And the French oil company TotalEnergies has a massive 38,000 ha acacia plantation project to offset its emissions in the Republic of the Congo. Investigations into all three projects point to severe impacts on local farmers.[42]

Two of Japan’s top energy firms are also deep into carbon offset plantations. Marubeni has a 31,000 ha pine and eucalyptus plantation project in Angola with an Argentinian businessman.[43] Mitsui, through its Australian subsidiary New Forests, is erecting tree plantations for carbon credits on leased farmlands in northern Tasmania and, through its African Forestry Impact Platform, it recently acquired Green Resources AS, “a Norwegian plantation forestry and carbon credit company notorious for its history of land grabbing, human rights violations, and environmental destruction across Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania”.[44]

Thanks to the Data Sciences Institute of the University of Chicago, Linda Pappagallo and Manveetha Muddaluru for their help with the dataset.

Subscribe to GRAIN

Meanwhile the climate alarmists are utterly silent on how artificial intelligence (AI) and cryptocurrency, the newest energy hogs, are increasing the demand for both new and old energy sources. That’s on top of greenwashing the new energy sources by calling them “clean” when in truth there’s nothing clean about any man-made energy source.