Human genome editing summit haunted by spectre of eugenics

by Claire Robinson | Mar 27, 2023

The Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing, held earlier this month at the Francis Crick Institute in London, closed with a statement that “heritable human genome editing remains unacceptable at this time”, adding, “Public discussions and policy debates continue and are important for resolving whether this technology should be used. Governance frameworks and ethical principles for the responsible use of heritable human genome editing are not in place.” Pointing to “risks and unintended effects” of gene editing, the statement warned that “Necessary safety and efficacy standards have not been met.”

The statement may have prompted sighs of relief from those who were concerned that the summit’s participants would exploit the event to immediately push for changing the law banning human germline (heritable) genetic modification (HGM) in the UK. Indeed, it was a significant step back from the conclusion of the previous summit on HGM in 2018, which concluded that “it is time to define a rigorous, responsible translational pathway” toward clinical trials of germline editing.

But the statement failed to meaningfully engage with the biggest ethical question around HGM. It focused on how to make the technology acceptable by improving “safety and efficacy”, while failing to lay to rest the spectre of eugenics that loomed over the summit. The anti-eugenics group Stop Designer Babies has pointed out that legalising HGM will inevitably lead to a eugenic society of genetic “haves” and “have-nots” in which wealthy parents can choose “designer” traits in their babies, such as skin, hair and eye colour, IQ, and athletic prowess. In the worst case scenario, those who can’t afford genetic “enhancement” would be banned from reproducing. And the statement doesn’t clarify whether, if scientists manage to solve the safety issues yet “public discussions and policy debates” come up with the answer that HGM should continue to be banned on ethical grounds, that decision will be accepted.

This question must be faced head-on because contrary to common belief, eugenics didn’t die with the Nazis. It is very much alive and kicking in scientific circles in the UK and US. Yet conspicuously absent from the publicity around the summit were the disconcertingly eugenicist connections and views of some of the scientists associated with it and, historically, with the venue that hosted it, the Crick Institute. That topic will be returned to later in this article.

Exploiting people with genetic diseases

The media coverage of the Crick summit – featuring quotes from its participant and allied scientists – was far less cautious than the summit’s official closing statement. The media strongly focused on the claimed need to gene edit humans to cure serious genetic diseases that lead to disability. For example, the Observer’s science editor Robin McKie wrote, “Ministers must consider changing the law to allow scientists to carry out genome editing of human embryos for serious genetic conditions – as a matter of urgency.”

To back his bullish position, McKie quoted not the organisers of the summit, but the findings of “a newly published report by a UK citizens’ jury made up of individuals affected by genetic conditions”. That report, said McKie, is “the first in-depth study of the views of individuals who live with genetic conditions about the editing of human embryos to treat hereditary disorders” and was presented at the summit.

Who could possibly argue with that? Except that as Dr David King of Stop Designer Babies has pointed out, “There is no unmet medical need for HGM, so why is this summit even discussing it?” Available alternatives for genetic diseases include genetic screening of IVF [in vitro fertilisation] embryos, adoption, donor eggs or sperm embryo screening, or somatic gene therapies. The latter are not heritable, only affect the patient, and don’t raise the ethical concerns about eugenics that plague heritable HGM. Although somatic cell genetic manipulation could, in principle, also be used for “enhancement” (e.g. improved athletic performance), this would not be heritable and it’s already been banned by the International Olympic Committee, as it’s seen to offer an unfair advantage akin to performance-enhancing steroid hormones. In addition, although major safety and efficacy issues persist with somatic cell gene therapy, which need to be addressed, this is also true of heritable HGM.

There are also indications that the citizens’ jury was manipulated and deceived. Pete Shanks of the Center for Genetics and Society noted that in their discussions of heritable gene editing, the citizens’ jury participants were asked to make the questionable assumption that the technology would be safe and effective. That’s false – many research studies have found that gene editing causes genetic errors, which could result in cancer or other severe diseases. It only takes an edit in a single cell to go wrong to result in a cancer down the line.

The ghost at the feast

Anyone reading McKie’s article would assume that the push for legalising HGM was driven by patients with genetic diseases. But that is not the case. The “ghost at the feast” who is not mentioned in the article is one of the organisers of the summit and its most prominent front man, the Crick Institute’s Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, who gave the Eugenics Society’s Galton Lecture in 2017. Yes, there still is a Eugenics Society in England, founded in 1907 and still going strong.

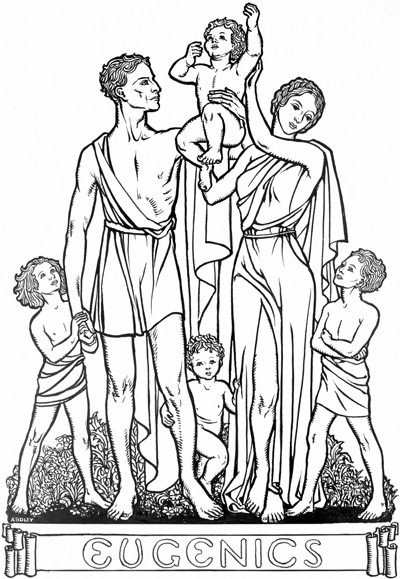

“Eugenic Family” – the emblem of the library of the Eugenics Society in the 1930s. Image via Wiki Commons from the Galton Institute, formerly the British Eugenics Society, now rebranded as the Adelphi Genetics Forum. For more, see this.

Lovell-Badge has found his way onto every committee involved in organising efforts to weaken the rules around HGM, most notably the key committee advising the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) on plans to change the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act later this year.

Lovell-Badge recently got excited about the seriously dystopian idea of “super-soldiers” genetically engineered to tolerate exposure to biological weapons. He also refers to GM “Super Humans” in the current Cut and Paste exhibition at the Crick.

The genetic have-nots: “Deaf, dumb, and blind”?

Prof Jennifer Doudna, who shared the 2020 Nobel chemistry prize for her role in inventing CRISPR gene editing, has enjoyed an image makeover similar to Lovell-Badge’s in the current PR blitz in support of HGM. She is quoted by the Guardian as excitedly predicting, “We’ll definitely be seeing genomic therapies for heart disease, neurodegenerative diseases, eye conditions and more, and possibly some preventative therapies as well.”

That’s all well and good, provided they are somatic gene therapies, where the genetically engineered changes will not be carried over to future generations.

But what is conspicuously missing from the Guardian piece are Doudna’s broader views, such as those expressed in her book, A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution. The following quote, to those sensitive to eugenic tendencies, is chilling: “Gone are the days when life was shaped exclusively by the plodding forces of evolution. We’re standing on the cusp of a new era, one in which we will have primary authority over life’s genetic makeup and all its vibrant and varied outputs. Indeed, we are already supplanting the deaf, dumb, and blind system that has shaped genetic material on our planet for eons and replacing it with a conscious, intentional system of human-directed evolution.”

It is perhaps not coincidental that Doudna’s word choices – “plodding”, “deaf, dumb, and blind”, which she applies to natural evolution, in stark contrast to the brave new world of “human-directed evolution” – could have been taken straight from the eugenicists’ playbook when describing disabled and other genetically “undesirable” people.

Replay of 1997 Life Patent Directive

The hype surrounding the Crick summit is not the first time that people with genetic diseases have been exploited by those wishing to promote the genetic engineering and patenting of life. The Crick’s use of the citizens’ jury report to argue for the liberalisation of HGM is a chilling replay of events in 1997, where disabled people with genetic diseases were deceptively exploited to lobby for a change in EU law that enabled the patenting of living organisms and their genes. In fact, but for this tactic, agricultural GMOs would probably never have got off the ground.

The exploitation was led by people linked to the LM network, a bizarre and cultish group that favours no restrictions on extreme technologies or corporate power and has infiltrated the UK’s scientific bodies for many years. This group, known as the LM network, has over many years shamelessly exploited disabled people and people with genetic diseases to further its pro-corporate aims. And the evidence presented here suggests that it’s still doing so.

Back in 1997, as GMWatch’s Lobbywatch website reported, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) turned up at the parliament building in Strasbourg to vote on a law to allow patents on life. This law, if passed, would allow for the patenting of genes, cells, plants, animals, human body parts, and genetically modified or cloned human embryos.

But the Life Patent Directive was unpopular with the public and politicians. Only two years earlier, MEPs had vetoed the directive and were expected to do the same again.

As the MEPs approached Parliament, they were confronted by wheelchair-bound protestors in an event organised by the lobby group, the Genetic Interest Group (GIG). GIG director Alistair Kent had rallied protestors suffering genetic diseases by claiming that they were about to be denied the chance of a cure if MEPs did not vote for the Life Patent Directive. This time, the law passed. GlG’s lobbying is widely credited as having been decisive in its approval.

Complaints from patient interest groups

GIG’s action attracted complaints from the very patient interest groups it was supposed to represent. The groups pointed out that GIG’s policy had always been against gene patenting. Alistair Kent issued a letter restating the anti-patents-on-life views of the group, which were officially unchanged. So how did he come to behave in such a contrary fashion?

Commentators noted that GIG’s lobbying had been part-funded by SmithKline Beecham, a company lobbying aggressively for the Directive. But there may have been another factor besides money – GIG’s policy officer, John Gillott. Throughout the patents on life controversy, Gillott was running a guerrilla campaign against the very people who should have been GIG’s closest allies – environmentalists. “The Directive has been vigorously opposed,” Gillott wrote, “by environmental campaigners who say it is an aspect of the ‘race to commodify life’ which amounts to ‘biopiracy’.” Gillott dismissed such views as “rubbish peddled by the environmentalists”.

Gillott’s message board was a magazine called LM, of which he was science editor. LM began life in 1987 as Living Marxism, the monthly review of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). The RCP started out as a far-left Trotskyist splinter group. In the early 90s, however, it underwent a drastic ideological transformation. Its leaders turned their back on seeking mass working-class action.

The real contradiction in society lay, they seemed to argue, between those who believed in increased human dominance over nature and those who did not. They declared a war of ideas on those they saw as the enemies of human progress. The RCP’s new vision championed “progress” by opposing all restrictions on science, technology (especially biotechnology) and business.

Gillott was a key contributor to Against Nature, a Channel 4 TV series which promoted GM crops and represented environmentalists as Nazis responsible for death and deprivation in the Third World. Also featured in the programme was another LM contributor, Juliet Tizzard, then director of the science lobby group, the Progress Educational Trust, which supports embryo cloning and opposes restrictions on genetic technologies – and has strong links with the pharmaceutical industry. Tizzard was previously head of policy and communications at the HFEA, the organisation currently spearheading the push to legalise human genetic engineering.

The current chair of the Progress Educational Trust is Robin Lovell-Badge.

Entryism

While LM ceased publication in 2000, its spirit lived on in its offshoots. The RCP adopted the tactic of “entryism” – infiltrating an organisation to influence its direction. Suddenly its members were sharp-suited and organising seminars. By the mid 90s, Living Marxism had become the innocuous sounding LM, while the RCP had been liquidated. LM-ers were increasingly heard in media debates on contentious issues such as GM crops and climate change. LM-colonised lobby groups include Sense About Science, the Genetic Interest Group, the Progress Educational Trust, and the Science Media Centre. Sense About Science and the Science Media Centre have consistently promoted GM crops.

Lovell-Badge is on the board of trustees of Sense About Science and is a regular spokesperson at the Science Media Centre in defence of the interests of these organisations, which align with those of their corporate funders.

HFEA: Regulator or lobbyist for HGM?

Currently in the UK, research is allowed on discarded human embryos from fertility treatment, but the embryo must be destroyed after 14 days and cannot be implanted for a pregnancy. But the Human Fertilisation and Embryo Authority (HFEA), the UK fertility regulator, thinks that the law should be changed to make it “fit for purpose” and “relevant”, now that science and society have allegedly “moved on”. Again, the HFEA keeps the focus on new “treatment options” for people with serious genetic disorders.

How is it acceptable for a regulator to push for changes in the law to suit a minority lobby that is deceiving and exploiting people with genetic diseases is a question that doesn’t seem to occur to the mainstream media, or indeed to the HFEA itself.

A new kind of techno-eugenics

Stop Designer Babies warns that the current wave of hype around HGM for treatment of disease promoted by the Crick summit is really a move to normalise eugenics. The group says the legalisation of these techniques will inevitably and rapidly generate a commercial market for “enhancement” traits.

That danger is recognised in an article in the Guardian titled, “Forthcoming genetic therapies raise serious ethical questions, experts warn”, which rightly draws attention to experts’ fears that legalising human genetic engineering will fuel “a new kind of techno-eugenics”.

The experts see this development as unstoppable. Prof Mayana Zatz at the University of São Paulo, Brazil and founder of the Brazilian Association for Muscular Dystrophy, said she was “absolutely against editing genes for enhancement”, yet added, “There will always be people ready to pay for it in private clinics and it will be difficult to stop.” Prof Françoise Baylis, a philosopher at Dalhousie University in Canada, believes genetic enhancement is “inevitable” because so many of us are “crass capitalists, eager to embrace biocapitalism”.

However, if the current widespread bans on human germline genetic engineering remain in place, a eugenic future is not inevitable. Stop Designer Babies points out that 70 countries ban HGM because of its inevitable trajectory towards eugenics. So if the UK legalises HGM, it will be an anomaly.

Worryingly, the recent wave of media articles, including those in the Observer and Guardian, don’t even entertain the idea of retaining the current ban – which after all is as simple as keeping the status quo. Instead they focus on how HGM can be governed once it’s (allegedly inevitably) legalised. That’s a perverse choice, given that there are workable alternative solutions for genetic diseases (as mentioned above).

Eyewatering cost

While the Guardian article notes that there are “serious ethical questions” around HGM, the main ethical question highlighted in the article is the eyewatering cost of gene therapies, which “will put them out of the reach of many patients”.

This is correct – gene therapies often cost millions of dollars per dose, meaning that they will not be widely deployed even if they have been proven effective in treating the targeted conditions. This could lead to a society divided between those who can afford to genetically engineer their children and those who can’t, leading to discrimination in many spheres of life and even to a ban on the “genetic have-nots” reproducing.

UK and US: World leaders in eugenics

Stop Designer Babies places the Crick’s summit in the context of a long and continuing history of eugenic thought and practice, in which UK and US scientists have played a leading role over decades. Notable among these scientists was the English scientist Francis Crick, under whose name the Institute was set up, and the American James Watson. As well as being the discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953, Crick and Watson were keen eugenicists.

For example, Crick said, “We have to ask, do people have a right to have children, or at least to have as many children as they please?… And if the child is handicapped, wouldn’t it be better to let that child die and have another one? And what about a child that is born incurably blind? Is there any reason nowadays for keeping such a child alive? In other words, should we not have an acceptance test for children?”

HGM: Ethically unacceptable

While the new push for legalising HGM is presented as offering cures for otherwise incurable genetic conditions, this is deceptive. Workable and ethical solutions to genetic diseases are available now and non-heritable somatic gene therapies are being researched. Even if currently safety issues are overcome, heritable HGM will always be ethically unacceptable. The organisers of the Crick summit have not firmly rejected heritable HGM on ethical grounds, so we are not reassured about their intentions. Legalising heritable HGM would represent a step on the slippery slope to a eugenics-based society.

0 Comments