Israel’s Architect of Ethnic Cleansing

by Stefan Moore | Apr 23, 2024

Since 1948, Israel has invoked the Holocaust to justify the forced expulsion of Arabs from Palestine to create a Jewish state, but the systematic blueprint for ethnic cleansing was being drawn up years earlier by a Zionist zealot named Yosef Weitz.

In November 1940 – eight years before the founding of the state of Israel – Weitz wrote:

“It must be clear that there is no room in the country for both peoples … If the Arabs leave it, the country will become wide and spacious for us …. The only solution is a Land…without Arabs. There is no room here for compromises… There is no way but to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighbouring countries … Not one village must be left, not one tribe… There is no other solution.”

Weitz was “a quintessential Zionist colonialist,” writes Israeli historian Ilan Pappé. Born in Russia in 1890 and immigrating to Palestine as a child, Weitz would become the influential head of the Land Settlement Department of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) created to colonise Palestine by purchasing Arab land for the Yishuv (the immigrant Jews in Palestine before 1948).

As head of the Land Settlement Department, Weitz oversaw the program to purchase properties from absentee landlords and run the Palestinian tenant farmers off their land. But it soon became clear that purchasing small lots of land would not come close to fulfilling the Zionists’ dream of creating a Jewish majority state in Palestine.

In 1932, when Weitz joined the Jewish National Fund, there were only 91,000 Jews in Palestine (roughly 10 percent of the population) who owned a mere 2 percent of the land.

Yosef Weitz in 1945. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Changing that demographic reality called for a radical two-pronged solution first, to convince the British Mandate in Palestine to allow more Jewish migration and, simultaneously, develop an efficient program to expel indigenous Palestinians.

To tackle the problem, the Jewish Agency set up a “Transfer Committee” in 1948 (the idea was Weitz’s) to come up with more robust plans to evict Palestinians and enforce their relocation in neighbouring Arab countries.

With his background in land settlement, Weitz was a natural choice to spearhead the prominent three-member group which included Israel’s future first president, Chaim Weizmann, and future Prime Minister Moshe Shertok.

Thanks to Weitz’s obsessive commitment to the mass expulsion of Palestinians he became known as the “architect of transfer” — a euphemism for ethnic cleansing (a recognised form of genocide) that would reach its apotheosis in the Nakba of 1948.

Yitzhak Rabin with Yosef Weitz (pointing at map on right) in the Yakir forest in the Negev in undated photo. (IDF/Wikimedia Commons)

Invoking the Old Testament, Weitz recounts a tour of Palestinian villages in June 1941 with messianic zeal:

“There is no room for us with our neighbours. . . . development is a very slow process . . . . They [the Palestinian Arabs] are too many and too much rooted [in the country] . . . . the only way is to cut and eradicate them [the Palestinian Arabs] from the roots. I feel that this is the truth . . . I am beginning to understand the essence of the MIRACLE which should happen with the arrival of the Messiah; MIRACLE does not happen in evolution, but all of a sudden, in one moment. . .” (Weitz’s emphasis)

Although Weitz’s Transfer Committee devised the first systematic plans to expel Palestinians, its roots reach back to the birth of the Zionist movement.

As early as 1895, Zionism’s founder Theodor Herzl declared:

“We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border…denying [Palestinians] any employment in our own country.”

Other early Zionists, such as Israel Zangwill, were less restrained:

“We must be prepared either to drive out by the sword the Arab tribes…or to grapple with the problem of a larger alien population.”

By the early 20th century, the alarm bells were already going off across historic Palestine; clashes between Jewish settlers and Palestinians were on the rise.

Crowd of Arab demonstrators in Jaffa advancing toward the police force in the square, October 1933. (Library of Congress, Public domain)

But the spark that would ignite the entire region was the 1917 Balfour Declaration announcing Britain’s support for a Jewish homeland in the British Mandate of Palestine.

It was a fateful promise that was, in the words of the late Palestinian-American academic Edward Said, “made by a European power … about a non-European territory … in a flat disregard of the native majority residents in that territory.”

It would engulf Palestine in ceaseless conflict and pave the way to the Nakba in 1948.

Over the following two decades Jewish immigration increased from a trickle to a flood – 60,000 in 1936 alone. As more Palestinians farmers were driven off their land and into poverty, resistance grew, exploding in the Great Arab Revolt of 1936-39 — three years of demonstrations, riots, strikes, bombings, sabotage and bloody clashes between Palestinians and Jews, finally brutally crushed by the British army and the Haganah (Zionist militia).

By the time it was over more than 5,000 Palestinians and 300 Jews had been killed.

In the wake of the uprising Britain set up the Palestine Royal Commission, or Peel Commission, that recommended the partition of Palestine into two sovereign states, with the Arab state annexed to Transjordan. If Arabs refused to move from the Jewish state their transfer to Transjordan would be “compulsory in the last resort.” The same would be true for Jews who refused to leave the Arab state.

Unsurprisingly, the Palestinians strenuously rejected partition while the Zionists formally accepted the plan, secretly waiting to take over all of historic Palestine. Realizing the plan was unworkable, the British government ultimately rejected the report in 1938.

Lord Peel and Sir Horace Rumbold, chairman of the Palestine Royal Commission, after taking evidence from the Arab Higher Committee on the “Palestine disturbances,” 1937. (U.S Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Speaking in 1938, David Ben-Gurion (who would become Israel’s first prime minister) announced in a 1938 speech:

“After we become a strong force…we shall abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine…The state will have to preserve order – not by preaching but with machine guns.”

By the time Weitz joined the Transfer Committee, the stage had already been set for systematic ethnic cleansing of Arabs from Palestine.

The project that excited Weitz most was a list called the village files, a detailed registry of every Arab village in Palestine — their topographic location, access roads, quality of farmland, water springs, main sources of income, religious affiliations, the ages of the men and their level of participation in the Arab Revolt.

For military planners, the village files were a goldmine — a comprehensive roadmap for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine that would be implemented over the coming decade.

The catalyst came in 1947 when the British abandoned their Mandate and turned the Palestine problem over to the United Nations. From there, the rest is history: on Nov. 29, 1947 the U.N. General Assembly passed Resolution 181 that proposed to divide Palestine into two glaringly unequal states — one Jewish state with 56 percent of the land and an Arab state with 42 percent — even though there were twice as many Arabs (1.2 million) than Jews (600,000) living in Palestine.

Members of the Jewish Agency delegation study a map of proposed partition of Palestine at the United Nations interim headquarters, Nov. 12, 1947. (UN Photo/MC)

Once again, the Palestinians and all the Arab states totally rejected the Partition Plan. The Zionists were ecstatic — their vision of a Jewish state was coming to fruition and war with Palestinians and neighbouring Arab states was on the horizon.

“[Yosef Weitz] saw in the partition resolution and the coming hostilities the felicitous opportunity to set in motion long-nurtured plans” writes Palestinian historian Nur-eldeen Masalha. “His diary is replete with injunctions not to ‘miss the opportunities offered by the war.’ ”

On April 18, 1948, Weitz, drawing on his village files, wrote about the list of villages he wanted to be ethnically cleansed first:

“I made a summary of a list of the Arab villages which in my opinion must be cleared out in order to complete Jewish regions. I also made a summary of the places that have land disputes and must be settled by military means.”

Pappé describes what happened next. Called Plan D, it was the final Masterplan for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine:

“The orders came with a detailed description of the methods to be used to forcibly evict the people: large-scale intimidation; laying siege to and bombarding villages and population centers; setting fire to homes, properties, and goods; expelling residents; demolishing homes; and, finally, planting mines in the rubble to prevent the expelled inhabitants from returning…”

When it was over, more than half of Palestine’s indigenous population, over 750,000 people, had been uprooted; 531 villages had been destroyed; 70 civilian massacres had taken place and an estimated 10-15,000 Palestinians were dead.

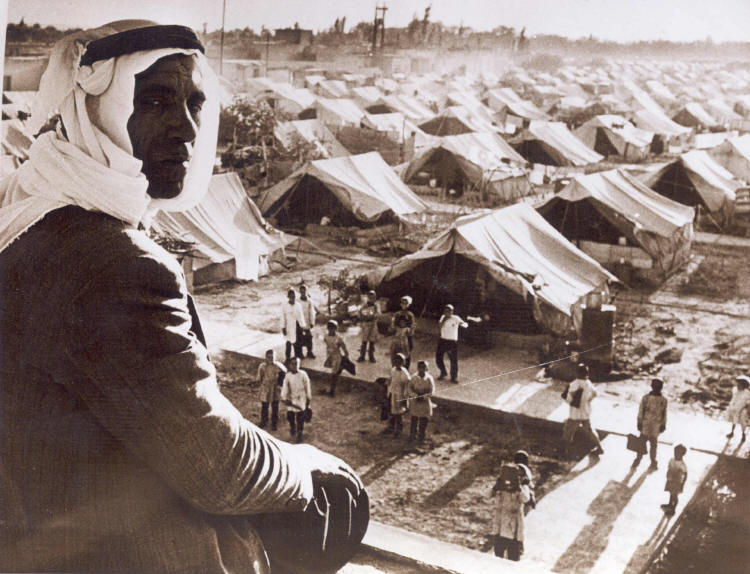

Jaramana Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria, established after the Palestinian Catastrophe, or Nakba, 1948. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Watching the destruction of one village, Weitz wrote:

“I was surprised nothing moved in me at the sight … no regret and no hatred, as this is the way of the world.”

Today, as the genocidal war in Gaza unfolds, the spectre of Yosef Weitz lives on. At the start of Israel’s invasion, the Israeli Intelligence Ministry drafted a wartime proposal to forcibly drive the Gaza Strip’s 2.3 million people, now under daily bombardment and imposed starvation, into Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula where they would be placed in tent cities and denied the right to return.

Meanwhile, the racist language used by Israel’s leaders to justify the mass eradication of Palestinians remains unchanged: “We are fighting human animals and we will act accordingly,” spits Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant; “This is a battle, not only of Israel against these barbarians,” intones Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “it is a battle of civilisation against barbarism.” And “There are no Palestinians, because there isn’t a Palestinian people,” declares Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich.

“It is tempting to dismiss the revival of transfer … as the wild ravings of right-wing extremists,” writes Nur-eldeen Masalha. “Such a dismissal is dangerous, however, and it is well to be reminded that the concept of transfer lies at the very heart of mainstream Zionism.”

The plan to ethnically cleanse Palestine is Israel’s original sin — one that the Jewish colonists either cannot acknowledge, think was justified or prefer to forget.

Since the Nakba of 1948, Israel has used the memory of the Holocaust to silence its critics and to thwart international pressure for a ceasefire in Gaza or for the rights of Palestinians to return to their land. But despite attempts to vindicate, minimise or deny their past, Zionists can never erase the legacy of Yosef Weitz or their blood-soaked history. It is well past time for Israel to acknowledge the inhumanity and futility of their Zionist project.

Stefan Moore is an American-Australian documentary filmmaker whose films have received four Emmys and numerous other awards. In New York he was a series producer for WNET and a producer for the prime-time CBS News magazine program 48 HOURS. In the U.K. he worked as a series producer at the BBC, and in Australia he was an executive producer for the national film company Film Australia and ABC-TV.

This article is from Pearls and Irritations.

0 Comments