Ivermectin: Can a Drug Be “Right-Wing”?

by Matt Taibbi

On December 31st of last year, an 80 year-old Buffalo-area woman named Judith Smentkiewicz fell ill with Covid-19. She was rushed by ambulance to Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital in Williamsville, New York, where she was put on a ventilator. Her son Michael and his wife flew up from Georgia, and were given grim news. Judith, doctors said, had a 20% chance at survival, and even if she made it, she’d be on a ventilator for a month.

As December passed into the New Year, Judith’s health declined. Her family members, increasingly desperate, had been doing what people in the Internet age do, Googling in search of potential treatments. They saw stories about the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin, learning among other things that a pulmonologist named Pierre Kory had just testified before the Senate that the drug had a “miraculous” impact on Covid-19 patients. The family pressured doctors at the hospital to give Judith the drug. The hospital initially complied, administering one dose on January 2nd. According to her family’s court testimony, a dramatic change in her condition ensued.

“In less than 48 hours, my mother was taken off the ventilator, transferred out of the Intensive Care Unit, sitting up on her own and communicating,” the patient’s daughter Michelle Kulbacki told a court.

After the reported change in Judith’s condition, the hospital backtracked and refused to administer more. Frustrated, the family turned on January 7th to a local lawyer named Ralph Lorigo. A commercial litigator and head of what he calls a “typical suburban practice,” with seven lawyers engaged in everything from matrimonial to estate work, Lorigo assigned one of his attorneys to review materials given to them by the family, which included Kory’s Senate testimony. The associate showed Lorigo himself the the material next morning.

“I was so convinced by what Dr. Kory was saying,” Lorigo says. “I saw the passion and the belief.”

Lorigo immediately sued the hospital, filing to State Supreme Court to force the facility to treat according to the family’s wishes. Judge Henry J. Nowak sided with the Smentkiewiczes, signing an order that Lorigo and one of his attorneys served themselves, and after a series of quasi-absurd dramas that included the hospital refusing to let the Smentkiewicz family physician phone in the prescription — “the doctor actually had to drive to the hospital,” Lorigo says — Judith went back on ivermectin.

“She was out of that hospital in six days,” Lorigo says. After a month of rehab, his octogenarian client went back to her life, which involved working five days a week (she still cleans houses). Her story, complete with photo, was told in the Buffalo News, causing Lorigo’s phone to begin ringing off the hook. Doppleganger cases soon began dotting the map all over the country.

One of the first was in nearby Rochester, New York, where the family of Glenna Dickinson went through an almost exactly similar narrative to the Smentkiewiczes: they read about ivermectin, got a family doctor to prescribe it, saw improvement, only to later have the hospital refuse treatment. Again Lorigo intervened, again a judge ordered the hospital to treat, again the patient recovered and was discharged.

Hospitals fought hard, hiring expensive law firms, at times going to extraordinary lengths to refuse treatment even with dying patients who’d exhausted all other options. At Edward-Elmhurst hospital in Chicago, a 68 year-old named Nurije Fype was admitted, put on a ventilator, and again, as all other treatments failed, her family got a judge to order the use of ivermectin. Lorigo claims the hospital initially refused to obey the court order, which led to the filing of a contempt motion, which in turn led to a pair of counter-motions and another confrontation before another befuddled Judge named James Orel.

“Why wouldn’t this be tried if she’s not improving?” the Chicago Tribune quoted Orel as saying. “Why does the hospital object to providing this medication?”

“He basically said, ‘What do you have left?’” Lorigo recounts. “No one would administer the ivermectin. It’s as safe as aspirin, for Christ’s sake. It’s been given out 3.7 billion times. I couldn’t understand it.”

Stories like these aren’t proof the drug works. They don’t even really rise to the level of evidence. People recover from diseases all the time, and it doesn’t mean any particular treatment was responsible. Short of the gold standard of randomized controlled trials, there’s no proof.

However, anecdotes have a power all their own, and in the Internet age, ones like these spread quickly. Lorigo estimates he now gets “10, 15, 20” calls and emails a day. At this level, at the bedside of a single Covid-19 patient who’s already received the full official treatment protocol and is failing anyway, the decision to administer a drug like ivermectin, or fluvoxamine, or hydroxychloroquine, or any of a dozen other experimental treatments, seems like a no-brainer. Nothing else has worked, the patient is dying, why not?

Telescope out a little further, however, and the ivermectin debate becomes more complicated, reaching into a series of thorny controversies, some ridiculous, some quite serious.

The ridiculous side involves the front end of Lorigo’s story, the same story detailed on this site last week: the censorship of ivermectin news that, no matter what one thinks about the evidence for or against, is clearly in the public interest.

Anyone running a basic internet search on the topic will get a jumble of confusing results. YouTube’s policies are beyond uneven. It’s been aggressive in taking down videos containing interviews with people like Kory and doling out strikes to independent media figures like Bret Weinstein, but an interview with Lorigo on TrialSite News containing basically all of the same information is still up, as are clips from a just-taped episode of the Joe Rogan Experience that feature both Weinstein and Kory. Moreover, all sorts of statements at least as provocative as Kory’s “miraculous” formulation in the Senate still litter the Internet, many in reputable research journals. Take, for instance, this passage from the March issue of the Japanese Journal of Antibiotics:

When the effectiveness of ivermectin for the COVID-19 pandemic is confirmed with the cooperation of researchers around the world and its clinical use is achieved on a global scale, it could prove to be of great benefit to humanity. It may even turn out to be comparable to the benefits achieved from the discovery of penicillin…

There clearly is not evidence that ivermectin is the next penicillin, at least as far as its effects on Covid-19. As is noted in nearly every mainstream story about the subject, the WHO has advised against its use pending further study, there have been randomized studies showing it to be ineffective in speeding recovery, and the drug’s original manufacturer, Merck, has said there’s no “meaningful evidence” of efficacy for Covid-19 patients. However, it’s also patently untrue, as is frequently asserted, that there’s no evidence that the drug might be effective.

This past week, for instance, Oxford University announced it was launching a large-scale clinical trial. The study has already recruited more than 5,000 volunteers, and its announcement says what little is known to be true: that “small pilot studies show that early administration with ivermectin can reduce viral load and the duration of symptoms in some patients with mild COVID-19,” that it’s “a well-known medicine with a good safety profile,” and “because of the early promising results in some studies, it is already being widely used to treat COVID-19 in several countries.”

The Oxford text also says “there is little evidence from large-scale randomized controlled trials to demonstrate that it can speed up recovery from the illness or reduce hospital admission.” But to a person who might have a family member suffering from the disease, just the information about “early promising results” would probably be enough to inspire demands for a prescription, which might be the problem, of course. Unless someone was looking for that information, they likely wouldn’t find it, as mainstream news even of the Oxford study has been effectively limited to a pair of Bloomberg and Forbes stories.

Ivermectin has suffered the same fate as thousands of other news topics since Donald Trump first announced his run for the presidency nearly six years ago, cleaved in two to inhabit separate factual universes for left and right audiences. Repurposed drugs generally have had a hard time being taken seriously since Trump announced he was on hydroxychloroquine last year, and ivermectin clearly also suffers from its association with Republican Senators like Ron Johnson. Still, the drug’s publicity issues go beyond the taint of “conservative” news.

The drug has become a test case for a controversy that’s long been building in health care, about how much input patients should have in their own treatment. Well before Covid-19, the medical profession was thrust into a revolution in patient information, inspired by a combination of Google and new patients’ rights laws.

Just as the Internet allows ordinary people to DIY their way through everything from stock trading to home repair, they now have access to tools to act as their own doctors, from caches of medical papers at sites like pubmed.gov to symptom-checkers to portals giving them instant looks at their own test results — everything they need, except of course the years and years of training, experience, and practice, and therein lies the rub.

In the waning days of the Obama administration, in December of 2016, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act. The New York Times headline, “Sweeping Health Measure, Backed by Obama, Passes Senate,” told the story, noting that Obama signed it over the objections of “many liberal Democrats and consumer groups,” adding rapturous praise of its bipartisan spirit that is weird to read now:

In many ways the bill, known as the 21st Century Cures Act, is a return to a more classic approach to legislation, with policy victories and some disappointments for both parties, and potential benefits for nearly every American whose life has been touched by illness, drug addiction and mental health issues. Years in the making, the measure passed 94 to 5 after being overwhelmingly approved by the House last week.

A lot of things were in the bill, but it was pitched as a win-win for both pharmaceutical companies and patients “desperate for cures.” Essentially, the law cut away procedural requirements in the name of speeding access to pharmaceuticals, including the waiving of “informed consent” in cases where clinical testing “poses no more than minimal risk to the human subject.”

On page 149, section 4006, the law also contained a passage — Empowering Patients and Improving Patient Access to Their Electronic Health Information — that would have serious consequences for some hospitals. The section required that providers create a portal with a “single, longitudinal format,” through which patients would have access to their medical information, including test results. The idea, promoted by Obama throughout his presidency, was to create partnerships between doctors and patients, giving people more of a say in their own care.

In theory, patient access sounded great. In practice, results have been all over, with some doctors cheering and others wanting to strangle the authors of the bill. There are tales of patients learning from their phones they have cancer or other terrible diagnoses before a human being can tell them — “not always, but not infrequently, either,” is how one E.R. doctor put it. In other cases, patients see their bloodwork as they wait and Google their way into states of panic, or compiling lists of (often irrelevant) questions before their doctors return, which not only chews up care time but in some cases triggers intense disputes over treatment. A typical picture might involve doctors refusing patient demands for antibiotics or other drugs they think are indicated.

Mostly the change just added to tensions long ago ushered in by the age of “Dr. Google,” but in the Trump age there’s been a twist, as patients now not only question the competence of their doctors, but also their rectitude. Are they being billed deceptively? Given brand name drugs when there are generics available? Upsold unnecessary procedures? In the age of swindlers like Martin Shkreli and impossible drug prices like the $84,000 course of Solvadi, patients with some justice have learned to believe by default that the health care system is probably lying to them somewhere.

In one of Lorigo’s cases, a doctor prescribed ivermectin but refused to submit an affidavit to the court to that effect. Here, the Cures Act became a weapon for a patient to strike back against an intractable hospital system. “The patient’s husband went into her portal, and we submitted that information to the court,” Lorigo says.

The pandemic struck in the middle of a society-wide collapse in trust in institutions. Fewer than one in ten Americans, for instance, have a great deal of trust in either the FDA or pharmaceutical companies, according to an Axios/Ipsos survey last year. In a Reuters/Oxford survey of 46 countries that just came out this week, the United States ranked dead last in terms of trust in news media, with just 29% of Americans saying they trust the news. This is a particular problem with ivermectin, which through no fault of its own has become a symbol of the public’s changing attitudes in both arenas.

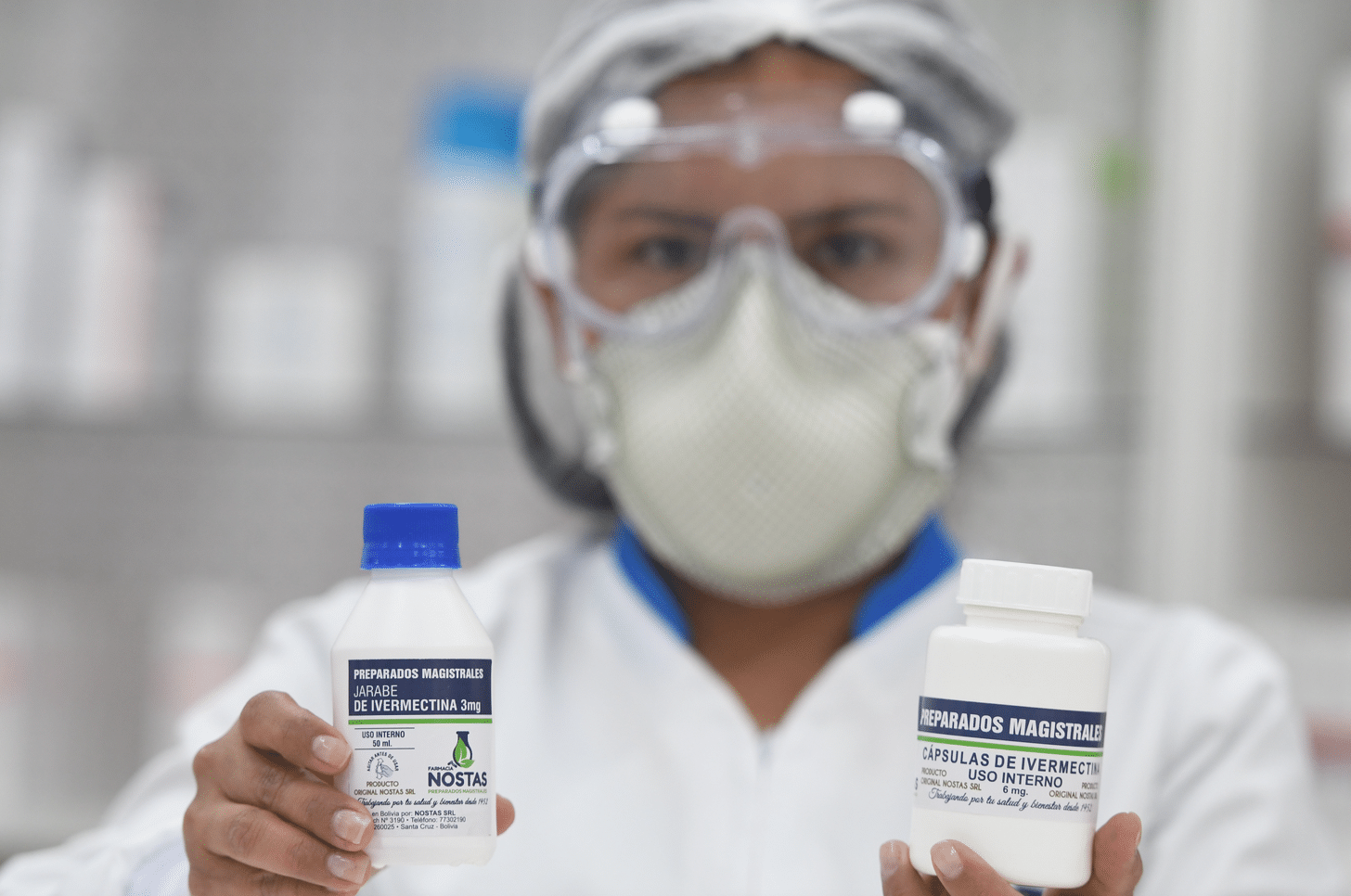

Doctors around the world have expressed frustration at the “populist treatment,” as it’s become common in Central and South America in particular for poor people to defy authorities and self-medicate with ivermectin. Experts frequently associate the drug with “pharmaceutical messianism,” i.e. politicians promising panacea cures, often in conjunction with rhetoric bashing experts and credentialed authorities. In the Philippines, for instance, President Rodrigo Duterte threatened the population with jail if they didn’t get vaccinated or take ivermectin, saying of people who avoid vaccines, “I will have Ivermectin meant for pigs injected into you.”

This phenomenon goes both ways. Just as medical authorities used the crudity of Duterte or Trump to argue that “populist” cures must be hoaxes, ivermectin advocates point to the constant shifts and deceptions of medical authorities to argue for ivermectin. When Kory and Weinstein went on with Rogan this week, Kory pointed to the shifting official guidance on seemingly obvious issues like whether or not Covid-19 could be spread by means of airborne transmission, or whether or not it was feasible to investigate a lab leak hypothesis when searching for the pandemic’s origin.

“To me,” said Kory, referring to the public shift on the lab leak question, “that’s an example of what’s called disinformation.” He went on to argue that when “science runs counter to the interests,” institutions lie. Kory presented this tendency of officials to disinform as part of his explanation for the suppression of ivermectin.

The drug has as a result ended up caught between two political movements — one populist, which believes officials are prone to lying and can’t be trusted, and one anti-populist, which associates theories about unapproved cures with political theories of stolen elections and other crazes. The former movement is sure the pharmaceutical companies are suppressing the drug because it’s been off-patent since 1996 and would imperil billions in revenues for vaccines and $3000-a-pop drugs like remdesivir if proven effective. The latter movement assumes ivermectin advocates are political grifters, cynically riding mistrust of the drug for votes, for headlines, and to undermine the authority of experts.

Caught in between are ordinary people and doctors like Bruce Yaffe, a New York physician known for a political discussion group he’s been holding since 1979. Yaffe (disclaimer: I first met Bruce decades ago) came across ivermectin as many physicians in the last year did, spotting the small Australian study showing that the drug seemed to inhibit the virus in vitro. He treated one patient, seemed to get results, and over the course of the next year treated a few dozen more, seeing enough good results that he felt more studies were at least warranted. “I don’t want to make any claims,” Yaffe says, “but I’ve been frustrated… I’ve been lobbying for someone to do a more aggressive study.”

The politically liberal Yaffe tried to contact various academic institutions to generate interest in starting trials, but hasn’t had luck. Politically liberal, he’s been dismayed to see the way the drug has become politicized, noting that even QAnoners are now taking up the cause.

It’s a vicious cycle: the more companies like YouTube suppress discussion of the drug, the more oxygen the topic gets with figures like former Trump lawyer Sidney Powell, which in turn creates more resistance as ivermectin gains a reputation as a “right wing drug.” This in turn accelerates the censorship Whac-A-Mole factor, which has the downriver effect of preventing stories like Judith Smentkiewicz’s from happening, because step one in each of those tales was a patient or a doctor spotting something on the Internet that, increasingly, isn’t there anymore, at least not for followers of mainstream media.

A secondary consequence: while there are plenty of doctors of all political persuasions showing interest in researching the drug, the public voices on the subject are almost exclusively either conservatives or denizens of alternative media. It’s no accident that Lorigo, in addition to being ivermectin’s de facto litigator in America, is also the Chairman of the Erie County Conservative Party. “Outside of Fox News, no one is covering it,” Lorigo sighs.

Should people on their deathbeds be allowed to try anything to save themselves? That seems like an easy question to answer. Should the entire world be allowed to practice self-care on a grand scale? That’s a different issue. Some would say absolutely not, while others would say the corruption of pharmaceutical companies and the medical system unfortunately make it a necessity. The world is increasingly divided along this trust/untrust axis.

Eventually, researchers like the Oxford group will complete their studies, and the public will have an answer. But this is going to take longer than it should, because of the one thing the ivermectin story has already proved: in a world split more and more into groups that don’t agree on anything, it’s nearly impossible to get everyone to agree on something, even if their lives depend on it.

0 Comments