Medical ethics – Best chance of restoring distorted health systems

by By Para Florescu, mission facilitator and Rob Verkerk PhD, Founder, Alliance for Natural Health | Apr 28, 2023

It’s Spring 2021. Jack Hurn, at just 26 years of age, is settling into his dream life. He’s a first class graduate with an automotive design degree. He’s got everything going for him; he’s compassionate, creative, vibrant and healthy. He lives with his girlfriend Alex in their new home in Redditch, Worcestershire (UK), one they’ve just bought. Jack’s planning to pop the question, and they’re both eager to start a family. Jack has no idea what’s around the corner.

The shine on Jack’s life starts wearing thin as he begins to deal with pounding headaches. These started just a few days after getting his first Covid injection. But it gets worse, much worse. Alex and his family see Jack disintegrate before them. Scans reveal a clot and numerous bleeds on the brain. Hours later, catastrophy ensues. Jack falls into a coma with dense right hemiplegia (paralysis on his right side). On the evening of 9 June, Jack’s body fails to cope with the extensive thrombosis and haemorrhages in his brain. Another shining, bright life lost. Dreams, plans, achievements and a life just beginning — all shattered within a few days.

Jack Hurn and his girlfirend Alex Jones. Courtesy Children’s Health Defence

Jack Hurn’s tragic story isn’t fiction. It’s real, especially for those left behind. It’s one of thousands that have been reported in the mainstream media (here, here, here and here). But there are so many more that have gone unreported.

Why Jack’s story matters

The medical system supposedly exists to do good – in the public interest. We know there can be risks inherent in any medical intervention, but interventions are generally selected when an assessment of risk and benefits weighs significantly in favour of benefit.

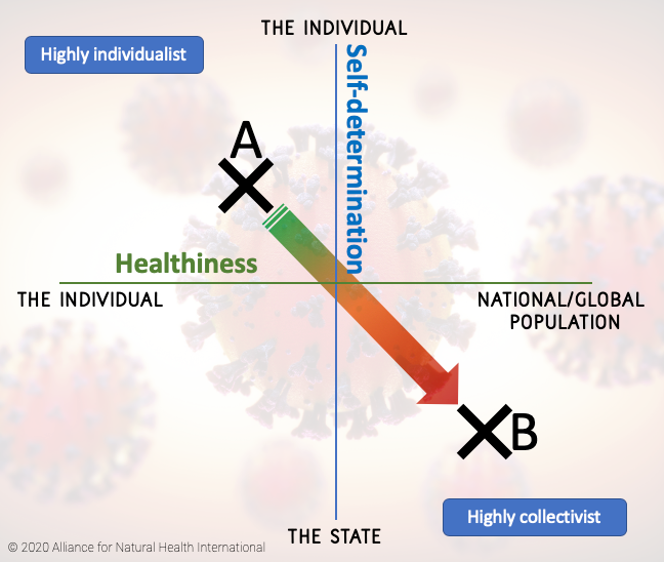

That long-standing view no longer applies. What has happened over the last 3 years has made sure of that. As the World Health Organization (WHO) further extends its powers under the proposed Pandemic Treaty and the International Health Regulations, individuals will have their right to self-determine their choice of interventions stripped from them, especially under conditions the WHO determines to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).

Science is the tool we use to assess risk and benefits, and law is the system that grants or deprives us of freedoms. Both have been abused by recent events and are working to an increasing degree against the public interest. They now serve stakeholders, governments and supranational organisations – all unaccountable to the people, including those who believe they still live in democracies.

But there is a third pillar about which we’ve heard very little over the last three yeas – and it may be the only system we have left to bring balance back into human societies. We’re talking here about ethics, the system humans have used over millennia to determine what is morally right or wrong, good or bad.

Think of a three-legged stool. The two legs of science and law are badly broken. Could the third leg stabilise things while millions of us around the globe continue to work to rebuild the scientific and legal systems that have been so distorted to serve, not the public interest, but the tiny proportion of globalists and corporations that are the current power brokers of human society?

Back to Jack. This is not just a scientific or medical issue concerning a new category of vaccines and its side effects. It’s a story of the profound erosion of ethical principles. It’s also a story that should shake the world of those who’ve put their blind trust in doctors and ‘the system’ and have been prepared to sacrifice their right to self-determination and bodily autonomy. More than that it throws into sharp contrast the opportunity cost of mass roll outs of interventions, the consequences of which are not well understood, and how they can tear away lives and the quality of lives of those left behind.

The authors discuss ANH’s new framework for health and ethics

Good ethics, good healthcare; bad ethics, bad healthcare

Ethics are not just a set of beliefs, philosophies, theories or laws intended for discourse among sociologists, philosophers and lawyers. They directly touch upon our lives and the lives of those around us through their values and principles that act as pillars for so-called civil societies, with the view to influencing or affecting many of our own decisions and behaviours.

Ethics are instruments that require a degree of flexibility and adaptability in order to meet the demands of an ever-changing world. However, despite this need for flexibility, there are principles that are still pertinent and that have their roots within ancient traditions or philosophies. These go back to the dawn of civilisation, and can be found in the oldest known writings, such as the Vedic texts of Ayurveda that date back over 4 millennia. More recently, we can look to the Ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato, Socrates, Aristotle and Hippocrates, and then the great Chinese dynasties of West Zhou and Qing.

As comprehensive as this 4000+ years of evolution of health-related ethics might have been, it is surprising how readily those who are responsible for delivering contemporary healthcare and public health will cast aside ethical considerations when they ‘get in the way’.

There might be more regulations, ethical codes, legislation and guidance documents relating to ethics in healthcare than at any other time, yet human dignity, respect, self-determination, and informed consent are among the many ethical principles that are now widely disregarded in practice.

Degradation of ethics

There are two key processes that have accompanied this erosion of ethical principles in medical practice. The first is the weakening of the relationship between doctor and patient, driven by 10 minute consultations, the growth of telemedicine and remote consultations, an approach that has been really catalysed during the covid-19 crisis.

Secondly, the almost universal adoption of the ‘pill for an ill’ model in general practice that requires several readily assessable symptoms, parameters or markers to be recognised or identified, a diagnosis made, followed by prescription of mass market, new-to-nature, pharmaceuticals developed around a largely biochemical model of disease. Thirdly, in parallel, we’ve seen an extraordinary shift in the locus of control in healthcare decision-making.

Ancient systems of healthcare were often quite, or very, paternalistic. The doctor was more of a god than a guide. But the doctor did expend considerable effort trying to understand the cause or causes of the underlying ailment, often interpreting an individual’s health from an holistic perspective. The value of the therapeutic relationship – the relationship between doctor and patient – was at the core of decision-making, even if decision-making was rarely participatory.

The arrival of external stakeholders – most notably the pharmaceutical industry, the tentacles of which extend deeply into all aspects of the medical establishment, including the institutions involved with medical education – led to a dilution of the value of the therapeutic relationship. That was a deliberate process instigated over the latter decades of the 20th century and was all about protecting stakeholder interests.

How could the newly emerging, medico-industrial complex formed out of the ashes of IG Farben, following the Nuremberg trials (e.g. BASF, Bayer, Agfa, Hoechst), act in its own self interest if doctors weren’t forced to prescribe these companies’ products? What if a doctor chose not to prescribe one or more of Big Pharma’s new fangled products (= patented, new-to-nature drugs) and used herbalism, vitamins (an early interest of IG Farben companies), homeopathy, osteopathy, meditation, forest bathing, or any other non-pharmaceutical intervention instead?

It was this kind of stakeholder-led approach that culminated in the emergence of self-serving regulatory regimes that were, in effect, obstacle courses specifically designed so only corporations with the might of the big pharmaceutical conglomerates able to negotiate them.

‘Pay to play’ medicine was born. Few would doubt that the WHO’s original mission when it was established in 1948 wasn’t laudable. As an institution that would act in the best interests of the people, funded by governments. Pay to play medicine has now ensured only 20% of funding comes from governments, 80% is now from stakeholders, of which the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi account for over 90%.

After 60 or so years of this pill-for-an-ill model of general practice, the big money-spinning blockbuster drugs hit a patent cliff, came under pressure from Indian and Chinese generics, and R&D pipelines were near empty.

A new model was needed. That model involved moving the focus back to infectious diseases and using entirely different platforms based on manipulating human genetic machinery. It also involved increasing globalisation and centralisation of the locus of control. The unaccountable, supranational World Health Organization would become the ultimate doyen and puppet-master of healthcare. Two years ago, we were all witness to this new revolution that was failing badly from the stakeholders perspective two years ago, when covid-19 genetic vaccines were rolled out on an unsuspecting public desperate to be released from lockdowns and return to normality.

What we really need now is an upheaval of modern ethics and an unearthing of those ancient principles that have been lost that still make sense today.

It is now more important than ever to ensure ethics isn’t something that’s just considered by erudite academics. It must find its way into the heart of health and medical practice, medical research and public health.

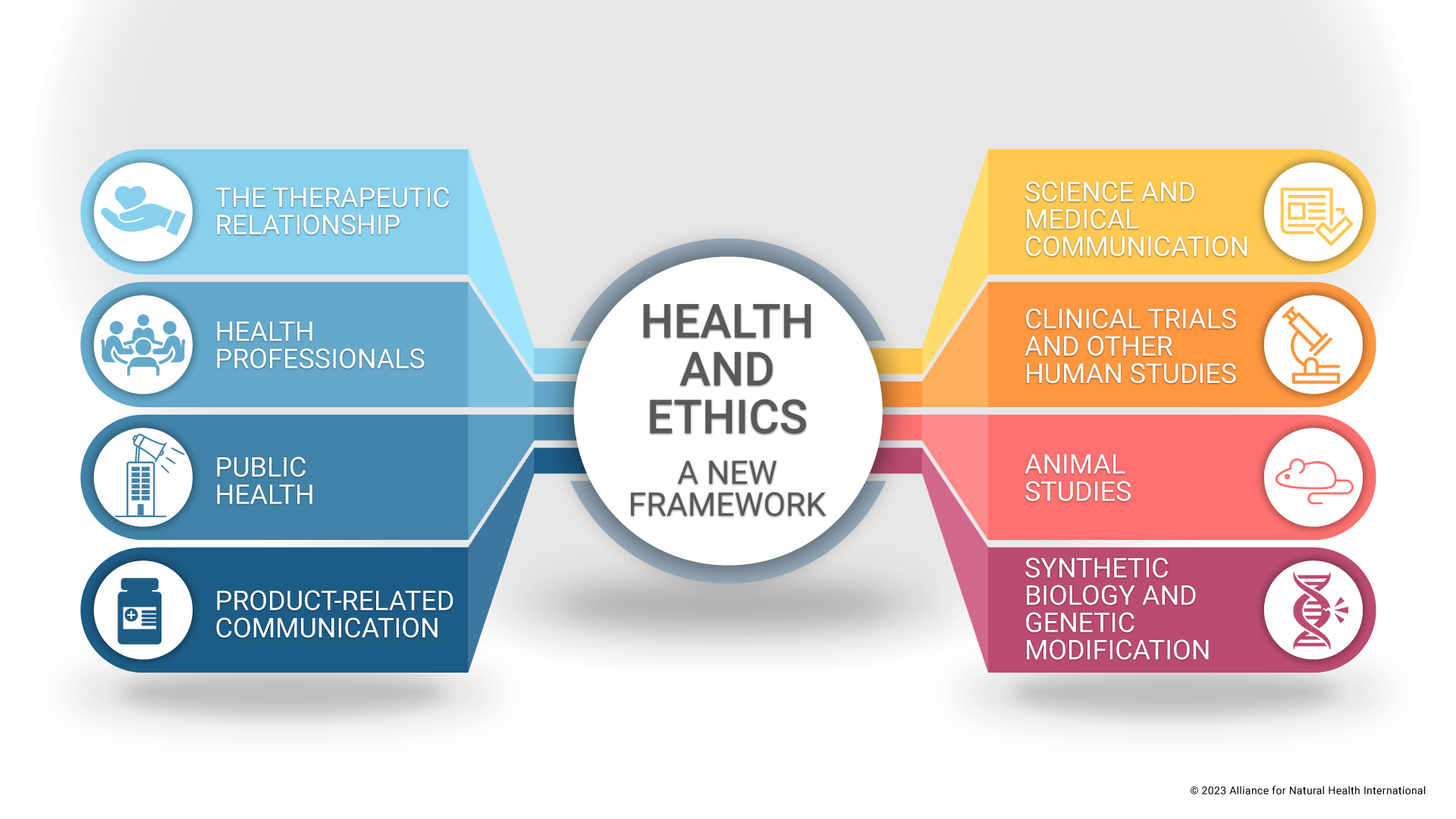

This is why we have been developing a new framework for ethics and health (see figure below), that covers not only the relationship between individuals and their practitioners, doctors, therapists or healers of all modalities, but also ethics that relate to clinical trials, for public health, for the use of new technology and synthetic biology and for the research involving risk to both humans and the environment.

Health & Ethics: A New Framework, from the Alliance for Natural Health International. The first pillar on the Therapeutic Relationship, is due for release next week.

Building on the four principles

The four principles of biomedical ethics first put forward by Beauchamp and Childress in 1979, and subsequently developed in subsequent editions of Principles of Biomedical Ethics, are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice.

Modern ethical codes are invariably built on these principles. Historically, various ethical principles often do not provide a practical guidance in how one should act, for example when confidentiality conflicts with the safety of the public, or autonomy conflicts with the patient’s best interests.

Beauchamp and Childress offer a “mid-level theorising” that promotes both the deontologist and utilitarian theories. They encourage reflective equilibrium, which requires not only theory, but also intuition, that includes experience, with regards to what is right in each individual case. There is a great emphasis on casuistry, where views are developed from looking at cases and deriving principles from these cases, rather than relying only on moral theory.

The four principles, however, are not enough in themselves. But they do provide a foundation for ethical codes. In addition to these four principles, we – as well as others – have identified a range of other important principles. As with all principles, they may be subject to different interpretations, so, in our new framework (that will be released next week), we have attempted to expand our propositions, while also giving explanations.

Perhaps most importantly, ethics should account for the “emotional element of human experience”, and this is why looking at the ancient ethical and virtue ethics is necessary in order to create an all-encompassing, holistic, ethical code. The ancients provide principles no longer found in modern ethical codes, such as the underpinning principle of Confucian medicine which upholds that, “medicine is not only a means to save people’s lives, but also a moral commitment to love people and free them from suffering through personal caring and medical treatment“. The notions of dharma and kãma in the Vedic traditions, notably the Ayurvedic Purusharthas, also propose that there should be a responsibility to offer love and ensure integrity within all relationships.

What went wrong in Jack’s case

With this background, let’s again reflect on Jack’s tragedy. Although autonomy was likely not directly infringed because Jack elected to receive his Covid-19 shot and was not ‘forced’ into it, there is no evidence of properly informed consent in which various options were considered and offered to him. This counter-argument, used by the medical board, that it was Jack’s choice, is simply the way clinicians avoid taking responsibility in the name of ‘autonomy’ and pass that responsibility fully on to their patients or surrogates, being a sort of “solitary autonomy”. The expertise, knowledge and guidance of the clinician is necessary and must be balanced with the idea of autonomy of the patient. That’s why we advocate that it is critical that physicians, or any health professional administering interventions that may present risks to patients, should act, within the ‘therapeutic relationship’, not as gods or dictators, but rather as guides.

Informed consent is not simply a formality, carried out verbally or as a paper exercise, but it requires that the patient understands fully the procedure and risks involved, communicated in a language that is understood. In Jack’s case, Jack was wrongly informed of the risk of having the injection, being told the risk of blood clots from the AstraZeneca injection to be 1 in 250,000 when, in reality, the risk has been determined by the UK Government to be 1 in 50,000 for those between 18 and 29 years of age. Consent cannot be ‘informed’ if the information provided is inaccurate.

In recent years, public and medical opinions have been formed without the benefit of the totality of available evidence, given key data and information have been withheld, something that is often only subsequently released via freedom of information requests.

This lack of transparency has been brought to light by the recently released, US Senate Muddy Waters report on the origins of Covid-19.

Finally, justice is not upheld as, despite the coroner raising concerns with the NHS Chief Executive, the board decided there was no wrong on the side of authorities and no further action was taken. It is increasingly difficult for individuals to successfully take cases like these to court and pass through all the regulatory loopholes that favour the mainstream narrative, going against ethical principles that seek to protect individuals.

It’s not just about Covid!

The transgressions of established medical ethics that have occurred since the covid-19 pandemic was announced, are without doubt key markers, that remind us just how unethical mainstream healthcare systems, health authorities and public health services have become.

But the media is replete with other stories of ethical atrocities. Take the children in Missouri who were allegedly prescribed hormone therapy in a Transgender Centre without parental consent and without accurate assessment of the needs of the children.

A whistle-blower revealed information in a formal affidavit about the practices of the centre, including doctors prescribing Bicalutamide, a drug that has no clinical backing on the use for gender transitions and is known to be highly toxic, triggering a cascade of adverse reactions.

Again, not only has informed consent often become little more than a box-ticking exercise, in many cases, it is being overridden in its entirety. How is a doctor showing beneficence through prescribing hormone therapy to a 13-year-old, a treatment known to come with a catalogue of deeply unpleasant side effects which may include severe atrophy of vaginal tissue, but also implications for the future life of that child by inducing sterility.

It is no easy task to build a new, future fit ethical framework for ethics relating to human health, but it may be a necessity for the survival of our species. The recent degradation of ethics appears to be spreading like a malignancy and if it isn’t arrested, the very foundation of our life, and future lives, will likely be compromised.

Ethics are so much more than just codes that try to harness specific behaviours and rein in others. They remind us of our inherent nature, of our connection with each other and the macrocosm, of the values that we should aim to embody in order to fulfil our human potential.

It’s the stories of people — those like Jack — that remind us just how lost we’ve become. It’s time for an unearthing of ethics and a reigniting of the moral compass that resides within each one of us, one that can act as a guidance system towards a brighter, more enlightened, and more natural future.

0 Comments