Open Wallets, Empty Hearts

by Ari Schulman | Aug 20, 2024

Shouldn’t charity serve the needs of recipients, not givers?

Isn’t it better to do more good than less?

Shouldn’t there be some way to measure that?

Effective altruism is the philosophy that answers “yes” to all these questions. Put this way, it sounds entirely innocuous. So why was it one of the hottest ideas in tech circles in the 2010s? And why is it playing a central role in so many Silicon Valley controversies of the 2020s?

If we use headlines as our guide, effective altruism has fallen from grace. One of its leaders, Eliezer Yudkowsky, also a founder of AI safety research, notoriously called in Time last year for global limits on AI development that are enforceable by airstrikes on rogue data centers. Sam Bankman-Fried claimed it as a motive for what turned out to be his multi-billion-dollar fraud. It reportedly drove board members of OpenAI to fire Sam Altman over concerns that he wasn’t taking AI safety seriously enough, a few days before some of them were pushed out in turn. And it has spurred the pro-AI backlash movement of “effective accelerationism,” which regards effective altruism as the second coming of Ted Kaczynski.

In public view, effective altruism shows up as a force of palace intrigue in the halls of Silicon Valley. And it is losing the favor of the court.

How did a movement based on an idea so obvious it seems trivial — “doing good better” — become so strange, and fall so dramatically?

Normie EA

To make sense of the odd parts of effective altruism, you have to first notice what seems normal and good about it. This is the face of the movement that it likes to show to the world. I’ll call it Normie EA. It is the part that will seem sane to ordinary people who know they’re not doing enough to help others and would be glad for better guidance.

In Normie EA there is much to praise. The research arm of Citibank estimates that, across the globe, people give $2.3 trillion every year in money and labor to charity. Effective altruists argue that most of this is wasted. If philanthropy is serious about doing good, then it must define what good it seeks, measure it, and fund the projects that do the most. But instead, people typically give to low-impact feel-good causes, and charitable foundations give based on fads, jargon, and personal relationships.

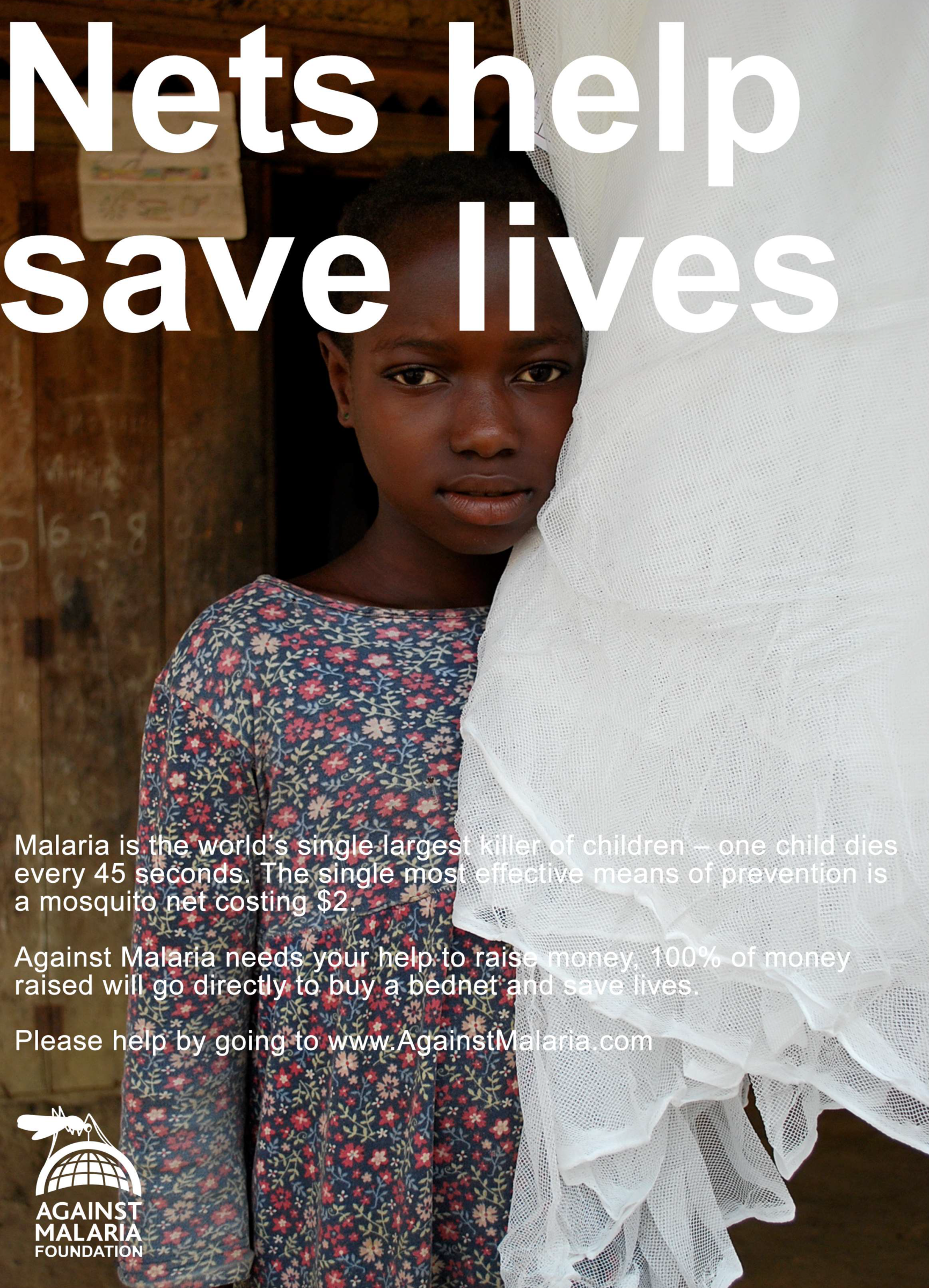

There are persuasive examples to back this critique. One of EA’s favorite causes is distributing mosquito nets to areas ravaged by malaria. The charity network GiveWell estimates that it costs $5,500 on average to save one life this way. Giving What We Can, a charity network founded by philosopher Toby Ord, claims that malaria prevention likely saves more lives per charitable dollar than cancer research, yet people in wealthy countries tend to give to cancer research instead, since they are likelier to know someone who’s had it. The Against Malaria Foundation, a leading malaria-net charity, took $58 million in its latest reporting year, compared to $658 million raised by the American Cancer Society. “We tend to care more about those who are close to us, even when we might be more capable of helping those who are far away,” chides Giving What We Can.

Effective altruism is also not just a set of ideas but of institutions. If you are an ordinary person who is looking to donate to a worthy cause, and you want to pick one based not on tugs at your heartstrings but hard data about which charities actually deliver, GiveWell provides that. It claims to have directed over $1 billion in giving to causes like mosquito nets, anti-malarial drugs, vitamin A supplements, and vaccinations, saving an estimated 215,000 lives.

And the movement inspires. Many followers have pledged to give 10 percent of their income, for life. One EA couple in Boston pledged to give 50 percent every year, and claims in one year to have spent only $15,000 of their $245,000 combined income, apparently saving the rest. Some go further still, embracing, like Sam Bankman-Fried, an “earning to give” philosophy: make as much money as you can, billions ideally, in order to give as much as you can to EA causes. Greed, for lack of a better word, is good — so long as you give well.

So skeptics of effective altruism can’t ignore these apparent success stories. It’s a refrain of movement leader Scott Alexander to exhort the movement’s critics to say plainly how much good they’re doing instead.

In the Gospels, Jesus praises a poor widow who donates pennies over the rich who gave more: “They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything — all she had to live on.” The committed effective altruist believes she has them both beat, giving out of her wealth, putting in more of it than others, and doing so much more good. Run-of-the-mill secularists who give a couple thousand a year to the Sierra Club, grad students raging against late capitalism, nuns who tend to the poor, dutiful churchgoers who slip a twenty in the weekly collection plate, a billionaire giving nine figures to get his name on the new computer science building at M.I.T.: Can any of them say the same? Can you?

Weird EA

But then there are the parts of effective altruism that are just … weird.

For many of its adherents, EA is not just an idea but a transformational lifestyle. There is no limit to how much of your time, money, and identity you can give over to it. EA is intertwined with the rationalist movement, so much so that they are virtually synonyms, different faces of the same set of thinkers, ideas, and organizations. There are formalized online communities. There are in-person meetups. For $3,900 a pop, you can attend four-day-long rationality training workshops at the Bay-area Center for Applied Rationality. Or you can just read up on what Eliezer Yudkowsky, whose work helped inspire the seminars, calls “The Way” of rationality: “The Way is a precise Art. Do not walk to the truth, but dance. On each and every step of that dance your foot comes down in exactly the right spot. Each piece of evidence shifts your beliefs by exactly the right amount, neither more nor less.” Yudkowsky, currently enjoying a moment as the world’s leading expert on AI safety research, was once better known for his FanFiction.net magnum opus Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, which spans nearly twice the length of Anna Karenina.

Finished the rationality seminar but still not quite dancing? Consider moving into a rationalist group house.

Weird EA also has exiles. What they recount is less an ordinary change of mind than a deconversion. In our pages (“Rational Magic,” Spring 2023), Tara Isabella Burton chronicled several whose attempt to fully live out the ideology brought them to what they describe as soul-breaking despair. Kerry Vaughan-Rowe, who claimed in a 2022 Twitter thread to chronicle his exodus, describes members who “were bright, energetic, dynamic people when they got involved. But over time it’s like the light fades from their eyes and their spark slowly fades.”

In contrast to these debased stories are the leaders who get special privileges. These include a castle in the Czech Republic bought by an EA organization, and the “Effective Altruism Castle,” a fifteenth-century manor house outside Oxford bought by Toby Ord’s Centre for Effective Altruism for £15 million (to wit: 3,458 lives otherwise saved through malaria prevention). All this is nominally to do good better, better.

Wytham Abbey, the “Effective Altruism Castle” near Oxford Flickr / Dave Price (CC)

Then there is the uncomfortable or odd sex stuff, including a 2023 report from Time of sexual harassment and abuse in one of those group houses, and the pervasiveness of polyamory, which is widely practiced in the community and intellectually defended by leaders like Peter Singer and Scott Alexander.

It’s hard to take in all these stories together and not think: cult. Weird EA comes with its own communes, overthrowing of folk morality, ascetic rituals for the low grunts and special privileges for the high priests, and a vision of the corrupt world to fall and the new world to come. Some cults promise deliverance from sin, some from wealth, desire, or worldly attachment. If effective altruism is in some ways a cult, what is it a cult of?

The Drowning Child

For some effective altruists, simply doing more to help, for people we’re not helping now, really is all that it’s about. Julia Wise, a former president of Giving What We Can and one half of the Boston couple mentioned above, counsels that it’s okay for people to pick and choose which parts of the philosophy work well for them. And Scott Alexander, a major EA figure and its most philosophically serious, argues against “extreme rationality” and says that the movement is about significant directional improvement rather than perfection. To these figures, the weird parts are just a sideshow. Should we judge every movement by its extremists?

If effective altruism really stopped at helping wealthy Americans save poor Africans from malaria, then there would be nothing to write about here. But it doesn’t. And it doesn’t because it offers itself no philosophical resources to do so. If you really want to be a moderate effective altruist — drawing, say, a little from the EA garden, a little from the do-unto-others garden, tossed together into an easy-to-chew do-gooder salad — you can. But you can do so only by drawing on ethical resources that are outside the ideology and that it is committed to condemning as irrational.

You can get a hint that effective altruism is ultimately totalizing just by looking at the names of some of its most influential associated blogs and texts: Overcoming Bias, LessWrong, Twelve Virtues of Rationality. Bias is bias, wrongness is wrongness, unreason is unreason, and once we set their elimination as the answer to everything, there is no obvious place where we should stop.

The problem here is not just an attitudinal one. Consider the famous “drowning child” thought experiment proposed by Princeton philosopher Peter Singer. Though later figures were more directly responsible for founding EA, Scott Alexander wrote in 2022 that “the core of effective altruism is the Drowning Child scenario.” Alexander is right — this specific scenario is a fixation of EA writing. And we can see in it that the movement’s problems grew right out of its intellectual roots.

Singer’s experiment, beginning in a 1972 paper in Philosophy and Public Affairs and expanded in later writings, asks us to imagine stumbling upon a child drowning in a pond, and then imagine another child drowning or starving or succumbing to disease on the other side of the world. Objectively, we must know that the distant child is no less urgent a problem than one I just so happen across: “If we accept any principle of impartiality, universalizability, equality, or whatever, we cannot discriminate against someone merely because he is far away from us (or we are far away from him).” Thus we must use reason to extend to distant causes an equal level of concern to those near. Singer, borrowing from the Irish historian William H. Lecky, calls this outward motion the “expanding circle” of moral concern.

One way to describe the difficulty with the thought experiment is what I’ll call the pencil problem. In his 1958 essay “I, Pencil,” Leonard Reed describes the immense number of minute calculations required to manufacture a single humble pencil. Countless actors stretching across the world and acting over years come together to achieve this feat. And, Reed argues, their result is achieved not by a single powerful mind that sees all but by spreading out the decisions, putting them in the hands of those who are closest to the relevant considerations. All of this is coordinated by a single powerful function: price. And it works. The messy marketplace makes a better pencil, more reliably, more cheaply than rationally elegant central planning.

At the risk of crudely reducing human moral experience to the base logic of commerce, we can make an analogy here to Singer’s experiment. Objectively, the weight of a near situation and of the same situation far away are equal. But let’s twist the scenario just so: imagine these situations are actually happening at the same time and I have to choose between them. Say I happen across a drowning child at the same moment that I’m watching a livestream of a drowning child in China on my phone. Do I just flip a coin? Of course not — my ability to help the child in front of me is far greater than the one in China. And I don’t need to do any sophisticated reasoning to arrive at this conclusion, either: I can just respond to the blaring signal that’s right in front of me.

Given a world where doing good, like doing anything, takes scarce resources of money, action, attention, and information, the pencil lesson can be extended some ways. I could imagine that, between saving children from starvation in China or helping run a food bank for the merely hungry in my own neighborhood, even though the faraway situation is objectively more weighty, I can do more good per unit of effort by volunteering at the food bank. Or I could decide that I should help a family in crisis in my neighborhood, rather than leaving that to a philanthropist in China or a well-meaning aid program in my state, because even though those actors have more funds, I am closer to the situation and have a fuller view of the problem.

By this account, the package of subjective faculties that effective altruists dismiss as biased actually serves an analogous function to the pricing mechanism. Empathy, guilt, the fact that I happen to notice a problem with my own eyes, a felt tug to act: none of these cognitive inputs are universal in scope, but that actually makes them quite useful, because they give me real information about the world that other people don’t have. They also give me real information about what I am well-situated to do, information too that others don’t have and that is specially relevant to my choices.

If we believe that our ethical aim is to maximize value in a world of scarcity, then we must grant the subjective, the parochial, our gut senses, and the happenstance of what is close to us as useful mechanisms for efficiently allocating ethical action, just as they are in commerce. It is only if we uncritically accept that rationality must look like the work of a collector — ever categorizing, ever tallying, ever expanding the database in which we can rank-order all things — that we will refuse to see any rational value in these human givens.

Well, fine, the effective altruist might want to say: the subjective has some informational value, for now. But that is just an accident of living in a scarce world, with finite computing, as limited beings making do with kludgy cognitive tools left to us by evolution. And don’t fret: effective altruism, already married to transhumanism, has plans to eliminate all these things too.

I, Paper

But this trouble is not merely a computational one. Consider the friendship problem. Namely: there are times where I am legitimately obliged to help my friends in ways I would not strangers. We can describe the obligation to the drowning child in the abstract: What is the child owed? But we cannot describe what we owe friends this way — What do I owe my friend? — for the obligation inheres at the level of the relationship, no lower. And this is not some grand scandal for enlightened philosophers to unmask, but is just what friendship is. What is affection if not choosy?

Even so, we might protest that rationalists could accommodate this point by adding a few annoying asterisks to their formalism — a scope variable, perhaps. But it is possible to make this point at a finer level, with more thoroughgoing results.

Consider a variation on the friendship problem: the humble paper towel problem. My colleague Samuel Matlack says that if you’re in a public restroom and see a paper towel on the floor, you should throw it away even if you weren’t the one who dropped it. Why? A version of broken windows theory: Public displays that minor violations of social trust are acceptable will eventually lead to major violations. Also, I am in a good position to pick up that one towel, whereas an epidemic of littering is beyond my power.

We should pick it up because it’s the right thing to do, but also because we know that all who pass by face the same choice, and we wish to encourage them to choose well, and by doing so to encourage still others. There is a nearly magical yet quite rational step of induction here: if the ordinary person takes responsibility just over what he happens across, it may be enough to coordinate others to do the same. Whether our shared life holds together or crumbles comes down to small choices like this.

Now back to where we started: when I see the paper towel, what is my obligation to? Certainly not to the paper towel. Perhaps it’s to the facility — a coffee shop or a public library. But I could just as well say it is they, the facility’s managers, who owe it to me to keep the restroom clean. The actual obligation is fuzzier than all this. It is to my place, my town, or, if I’m passing through, just to civic order. And the direct stakes are vanishingly small: the utility that hangs on whether or not I, on this one Tuesday afternoon, in this one bathroom, throw away this one paper towel approximates zero. No, the actual moral weight here resides in a principle. My obligation is not to the sum of all people but to my fellow human being as a category. It is a vote against turning daily life into a prisoner’s dilemma, a display of faith that asks others to do the same. It is a relation that arises because I cannot escape being somewhere, because I already find myself caught up with others in a scene.

A moral pull on this account is like gravity. Once I am near I will be caught in its well. To effective altruists, it is precisely when I am under the tug of a situation that I am subject to bias, and so must work hardest to escape. But on the account I am offering here, the feeling of being caught up in a tug is not some scandalous perceptual artifact to be discarded: it’s just what the tug is really like from that vantage point.

Imagine a would-be Newton who believes that his only hope for cracking the mystery of gravity is to get out from under the apple tree, off the planet Earth, out of the solar system, and start again from some desolate pocket of space. The distant view of the pull of things is not obviously the fullest one.

Empty Hearts

The spirit of the drowning child scenario — the moral problem it identifies, the path of the solution — is still the animating one for effective altruism. It is EA’s Magna Carta. Every effective altruist post is more or less just retreading Peter Singer’s argument, identifying some troubling ethical bias that besets human cognition and working through the logic problem of eliminating it.

The trouble that arose for effective altruism was not just that its proposed solution to the philosophical problem of ethics is intractable, but that solving this problem was never its real motivation. Go back to Singer’s original paper in the journal Philosophy and Public Affairs, where he lays the foundation upon which EA would build its edifice: “If we accept any principle of impartiality, universalizability, equality, or whatever, we cannot discriminate against someone merely because he is far away from us.” This is a universal leveling mandate. Discrimination is discrimination, equality is equality: contrary to what EA’s narrower interpreters argue, these are claims of justice that do not allow for piecemeal solutions, as the situation permits. Their whole point is to put an end to that kind of arbitrariness. But set aside real-world practicalities; just the theoretical challenges posed by this leveling mandate, the endless variations on the trolley problem we must work out, are overwhelming. And far from trying to work them out, Singer never even gets around in the paper to specifying what the principle is: we really may as well be acting on the principle of whatever. Achieving the universal system isn’t the point of the systematizing.

So what is the point? Based on the public reputation of Singer’s “expanding circle of moral concern” idea, you might expect to find in his writings calls for brotherly love and hugging panda bears. But actually it is filled with contempt for “heartwarming” causes, empathy for “animals with big round eyes,” and “sentimentalism.” People who give to help a kid with leukemia who they saw on TV are revealing “a flaw in our emotional make-up, one that developed over millions of years when we could help only people we could see in front of us.” Empathy on its own is a “trap.” Singer here sounds less interested in uplifting than debunking.

You can see this same dynamic in the work of flagship institutions like the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics or economist Robin Hanson’s Overcoming Bias blog, which have served as intellectual rallying points for effective altruism. They have routinely gone viral for “just asking questions” like whether we need to work through the ethics of using mind uploading to simulate sentencing vile criminals to a thousand years of hard labor, or whether there should be “sex redistribution” for incels. Go read the original posts and you will find not gadflies in the tradition of Socrates but the philosophical equivalents of shock jocks.

Or consider Eliezer Yudkowsky, the autodidact co-founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute and lead author of the most influential site of the EA movement, LessWrong. The site is gargantuan, spanning a group blog, comments section, and “The Sequences,” a series of 50 “foundational texts” by Yudkowsky that “describe how to avoid the typical failure modes of human reason.”

One Sequence outlines the “virtues of rationality,” of which there are twelve, including: relinquishment (“Submit yourself to ordeals and test yourself in fire. Relinquish the emotion which rests upon a mistaken belief, and seek to feel fully that emotion which fits the facts.”); lightness (“Let the winds of evidence blow you about as though you are a leaf, with no direction of your own…. Be faithless to your cause and betray it to a stronger enemy.”); and simplicity (“When you profess a huge belief with many details, each additional detail is another chance for the belief to be wrong.”). Does this strike you as the solution humanity has sought for thousands of years to the problems of ethics and epistemology? If not, what is it?

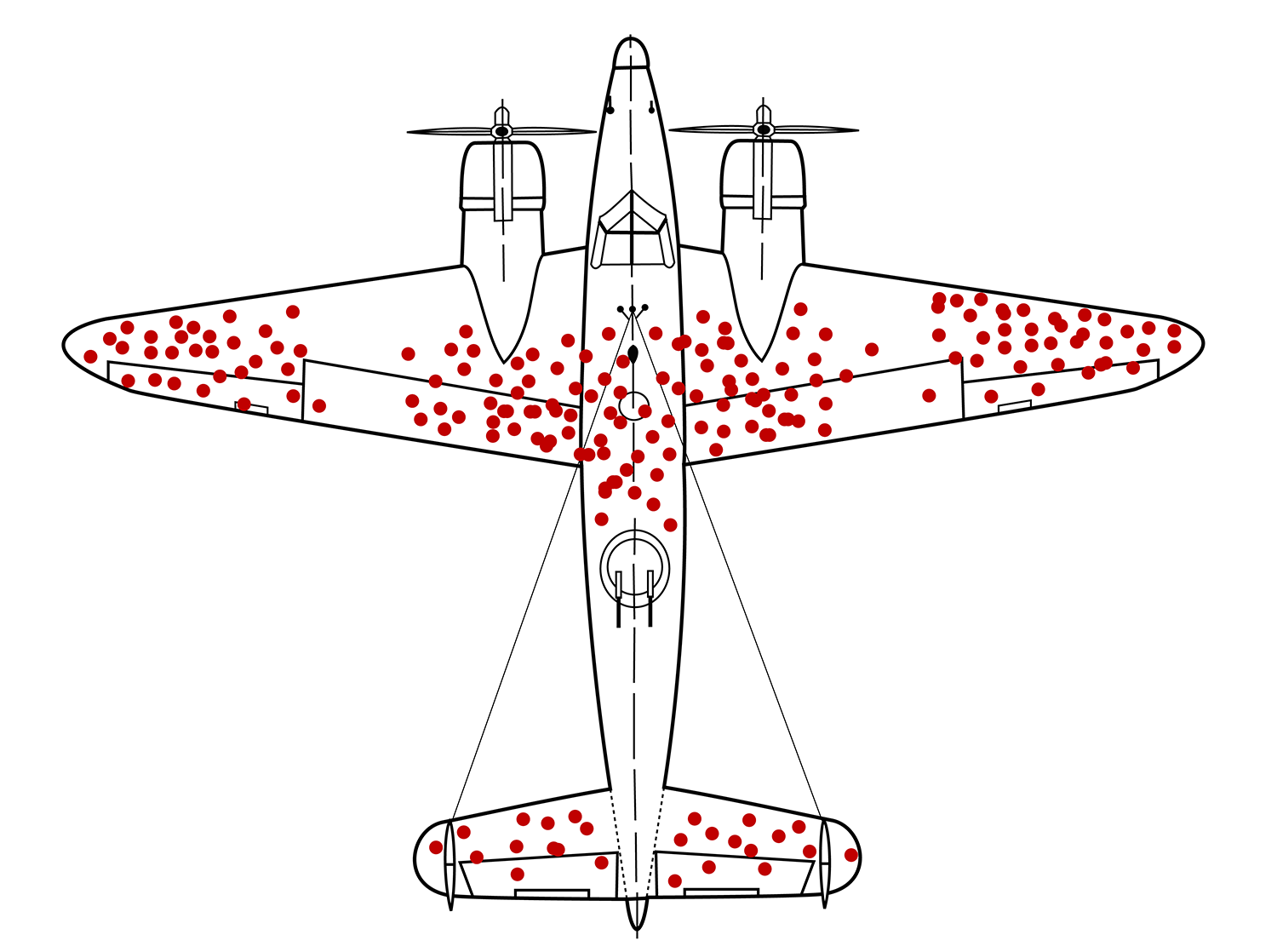

If you have spent any time talking to people in the tech world since the mid-2000s — and I have spent enough, first as a computer science student at the University of Texas, then as a coder, then as a public commentator — you will again and again encounter those gripped by this mindset, who in response to anything you say can rattle off the name of the specific cognitive bias you’re suffering from. You can say in certain online forums that you had a good morning and someone will find a way to work in that World War II bomber plane chart that stands for survivorship bias. You could mention that the sky is blue and be called out for your visibility bias. One post on LessWrong lists 140 cognitive biases. Wikipedia lists hundreds: “hindsight bias” (previously known as Monday morning quarterbacking), “availability cascade” (groupthink), “euphoric recall” (nostalgia).

Survivorship bias Allied researchers in World War II sought to reinforce bomber planes. This hypothetical chart shows the locations of bullet holes on bombers that returned from battle. It would be easy to argue that the planes needed reinforcement in the most heavily hit locations on the chart, but mathematician Abraham Wald recognized that the opposite was true: planes hit in the other locations were not returning from battle. Martin Grandjean, McGeddon, and Cameron Moll via Wikimedia (CC)

It’s easy to dismiss these examples as cherry-picking, but this rhetoric permeates EA literature. It is all over the website of Giving What We Can, which led the 10-percent giving pledge. There really are insights about cognitive fallibility you can gain from some of this writing, particularly in the works of Scott Alexander. But EA by and large follows Yudkowsky, seeking not marginal improvement but total rational transformation. Peruse any random entry in “The Sequences” or post on LessWrong and it reads as if it had just now invented the problems of philosophy and in the same post gotten a good start at solving them. The total effect is like the movie Memento, with each post beginning anew.

Even as effective altruism does seek many worthy ends — benevolence, consistency, fairness, truth — it is ultimately being driven by something like intellectualized impulsiveness and profound insecurity. The effective altruist adopts what literary theorists call the “hermeneutics of suspicion.” Corrupting forces are all around us, and they are so deeply seated in our world, in our brains, that reason cannot succeed by method alone. We must be ever on the hunt, ready to spot anything received and then make a public show of unmasking it.

The intellectual form we are seeing here is not philosophy; it is therapy. I do not mean this entirely as a pejorative. The need to cleanse one’s self of impurities is universal. So is the need to live in a community of fellow practitioners of a Way. These are the real needs EA fulfills for its followers, needs that many plainly did not know how to meet before. In that sense we should consider the movement a work of mercy.

But all this is no small irony. The grand promise of effective altruism was to be the first giving philosophy to focus entirely on the needs of others, but it wound up collapsing into another form of self-help.

It is stranger still when we recognize exactly what impurities EA promised to cleanse its followers of: sentiment, preference, personal connection, any emotion that exceeds calculation, a rooted point of view. The rationalist believes he is pursuing something when actually he is fleeing something, absolutely terrified witless that anyone might for one second mistake him for a human being.

Near and Far

All men are created equal, but we are born radically unequal, thrown together into a randomly cruel world. Some are born to wealth and with the genes of a piano prodigy. Others are born into war and with their brains half-formed. Some who find themselves in peril have someone there who runs to their aid. Others don’t. It is a question of deep obscurity why the world is arranged this way. But until the day of abolition arrives, each of us must choose what to do with the portion of fortune that fortune throws our way.

What is interesting about the drowning child thought experiment is that it is not randomly wrong, but comes very close to something true. There is a way to critique effective altruism and its flavor of rationalism as a kind of philosophical autism, if we take that to mean that it just struggles to make sense of an important dimension of human sociality. But Singer does not ask us to imagine a big spreadsheet. Of all the possible scenarios he could have conjured up, the one he picked identifies a profound existential problem, and is remarkably well attuned to the way that problem shows up for each of us.

The trouble is that the rationalists would have us believe that our given instincts here are precisely wrong. Imagine our circle of moral concern as a balloon. You might think that expanding it, as Singer urges, would look like pumping it fuller. But Singer actually wants us to pop it. Human empathy is not good and in need of a boost; it’s a biased embarrassment.

For this reason I believe that the drowning child thought experiment actually suffers from a failure of nerve. (I have argued this before in these pages.) The reversal it implies is more dramatic than even EAs typically argue. For if we really carry the logic through, then the starting premise — when I come across a drowning child, of course I should try to save it — now seems doubtful. Charged with the mandate to treat all like situations everywhere equally, when I encounter this one, I now might reasonably wonder whether I shouldn’t pull out a calculator and consult a spreadsheet before committing my time to jump in.

Let’s follow this point through. Imagine that you are Elon Musk. Over the past two decades, considering just your work running Tesla and SpaceX, your average working hour has helped generate $18 million in economic value. In mosquito-net terms — $5,500 per life saved — that works out to almost exactly one saveable life for every second you have worked. Can you save that drowning child in the pond in under a second? If not, you should really let it be and go back to your desk and donate to more worthy causes instead. This point isn’t entirely hypothetical: In 2018, Musk actually did spend a considerable amount of his own attention, and that of SpaceX and Boring Company engineers, working on engineering solutions to rescue twelve boys trapped in a Thai cave by monsoon floods — arguably a profoundly unethical use of his time.

You don’t generate as much wealth as Elon Musk, but all you have to do is imagine confronting a less weighty scenario than the drowning child for the same logic to apply. Think of a situation that feels personally urgent but you know is not the most important problem in the world: a friend in emotional crisis, a beggar mother and child you see every day. Is attending to these things the most ethically impactful use of your even more finite resources?

Singer’s thought experiment is not incidentally about these immediate scenarios we are faced with: it is precisely about them. I find myself caught in the situation. It feels to me like a real crisis. I feel tugged at, as if I were right there, because I am. I must then measure and balance. Am I responding to the scene out of self-interest, to satisfy my emotions and let happenstance control me? Or am I responding properly as the scene solicits me to act? These really are legitimate questions we all should ask about where we choose to put our moral effort and where we don’t.

The scenario thus invokes exactly the proper stakes — and dashes them. To wit: If “we cannot discriminate against someone merely because he is far away from us,” then we also cannot discriminate in favor of someone merely because he is near us. Only in the rarest of extreme circumstances is the scene I just so happen to stumble upon the one I objectively should be acting on. Nothing is ever at stake for me in where I am. The thing urged upon me, the question of how to be a person to another, is relievedly voided.

GiveWell’s ratings and rankings and spreadsheets have their place. Every one of those 215,000 lives saved mattered. Their plight does call on us, even from afar. We should celebrate this work, and if more is to come, celebrate it too. But the rationalists err in seeing this all as a useful occasion to atone for our cognitive sins. And the effective altruists fail in urging us to see this as the whole story, or even the main act.

There is someone I know who once drove by a bedraggled man pushing himself in a wheelchair along a dangerous highway. She stopped to offer him a ride, he accepted, and she kept providing this kindness for years whenever he called her to ask, even as she was caught up working and raising her children, even as she and this man never became good friends. Another time, an old friend of hers was slipping into a medical and financial crisis that the friend’s family wasn’t resolving, bogged down in problems of its own. She stepped in to serve as her friend’s caretaker for years until she had resolved the crises enough that the family could take back over. Another time, she took a young relative who needed a home into hers. There are many more such cases, of people whom fate put in her path and she was the only one to step up and help.

I asked her once why. She said she had never thought about the connection between these stories, or had some grand reason why she did it all. She just did.

Precious few of us have.

0 Comments