Subscribe to Zero-Sum Pfear & Loathing

by Maryanne Demasi, PhD | May 1, 2023

Quitting antidepressants is challenging for about half of people who take them, particularly if they’ve been medicated for prolonged periods. Danish data show that one third of people taking antidepressants continue to do so for the next decade.

For some it can take over six months to slowly taper off the pills, for others, they struggle to stop entirely. That’s because these psychoactive drugs alter the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain making it difficult for the brain to readjust to a drug-free state.

For decades, people have been told that antidepressants can “correct a chemical imbalance” in their brain, when in fact, the opposite is true – these drugs cause an imbalance.

Even though the “chemical imbalance” hypothesis has been convincingly discredited in a recent review published in Molecular Psychiatry, it has largely shaped people’s perception of what causes depression and makes them more likely to take antidepressants.

If someone abruptly stops taking the medication, or tapers off too quickly, they can experience symptoms of withdrawal, including dizziness, fatigue, headache, nausea, insomnia, flu-like symptoms, anxiety, and depression.

In rare cases, withdrawal symptoms can lead to suicide, violence, and homicide – and some patients report that withdrawal is worse than their original depression.

To an unskilled practitioner, these symptoms are mistaken for the relapse of the patient’s depression and results in reinstating the medication, rather than undertaking an extended tapering strategy to minimise withdrawal.

Most antidepressants bind to a receptor called the serotonin transporter (SERT) and withdrawing off these drugs requires a gradual and slow unblocking of these receptors.

Most doctors withdraw their patients by gradually reducing doses of the drug in a linear manner – i.e. the patient keeps halving the dose, often over a period of only 4 to 6 weeks.

But tapering should be done in a “hyperbolic” way over several months to a year because occupancy of the SERT receptor falls rapidly at lower doses.

Therefore, instead of continually halving the dose, reductions have to be made in smaller and smaller amounts as you get down to lower doses, and so the last dose before stopping may need to be as little as 2% of the starting dose.

Put simply, at the very end of the tapering regime, very small doses of antidepressants have very large effects on the brain. This is why the last few milligrams of a tablet are the hardest to stop.

Authorities have assured people that antidepressants are not addictive, but this is false. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are habit-forming and quitting the drug can cause abstinence symptoms.

A study showed that the symptoms of withdrawal from SSRIs are like those for benzodiazepines, the latter of which are widely acknowledged for their addictive properties.

In 2009, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) depression treatment guidelines suggested that withdrawal symptoms were “usually mild and self-limiting over about one week.”

But a freedom of information request for studies to support NICE’s claim revealed that not only did the agency lack evidence, but they also had sources contradicting its claims.

The ensuing criticism led to an update of the NICE guidelines in 2019, and then again in 2022, recommending that psychiatrists and mental health professionals talk with their patients about antidepressant withdrawal (see below)

Unfortunately, guidelines in other countries have not been updated sufficiently. For example, the Australian guidelines still recommend a “gradual dose reduction, with lowering by increments every few days, usually over a period of 4 weeks”.

The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders refer to hyperbolic tapering but say “reducing the antidepressant in such a way is impractical as current preparations of antidepressant do not allow for the dose to be reduced by such small decrements.”

What they’re actually saying is that it’s too difficult for patients to crush or evenly divide tablets or pills accurately.

However, there are practitioners who can help patients manage these hurdles. For example, they can reduce the dose by counting beads in capsules, buying a tablet guillotine at the pharmacy, using a nail file and a scale, or using a solution.

We recently completed a study in which we reviewed trials that analysed various ways of helping patients withdraw from antidepressants.

Our primary objective was to determine the success rate of patients attempting to withdraw from their medication using any intervention – and see how that impacted relapse, severity of symptoms and quality of life.

Of the 13 trials in our systematic review, we found that there was a huge difference in the chances of successfully withdrawing from antidepressants – it ranged between 9 and 80% – with a median of 50% (interquartile range 29% to 65%).

The main reasons for the huge variation between trials were that they all tapered patients off their pills far too quickly and they all confounded withdrawal symptoms with relapse.

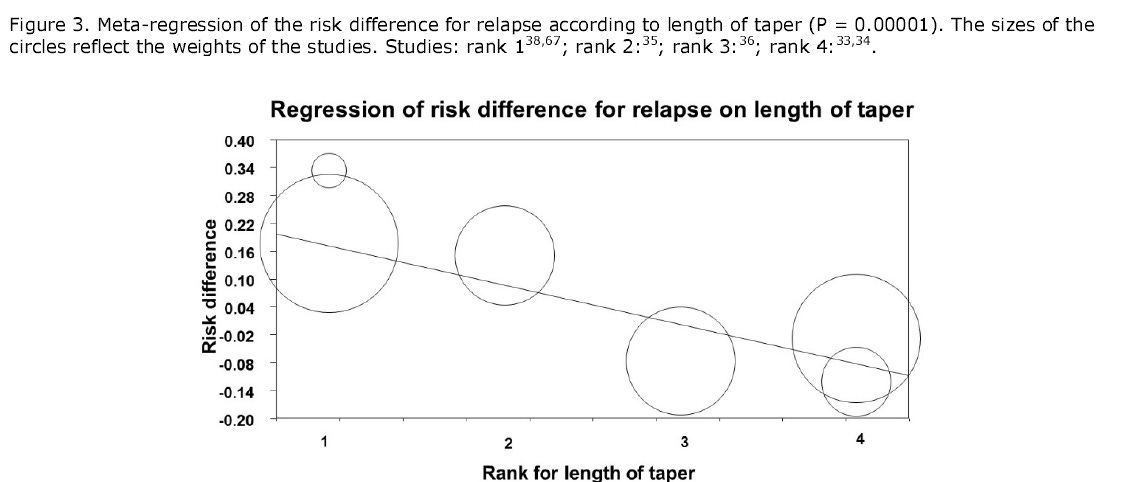

Of particular interest, we carried out a meta-regression showing that the length of taper was highly predictive for the risk of what the psychiatrists call relapse (P = 0.00001), i.e. the longer you taper off the pills, the greater your chance of success. It should be noted that what happens is rarely a true relapse but withdrawal symptoms that mimic a relapse.

Therefore, the true proportion of patients on antidepressants who can stop safely without “relapse” is likely to be considerably higher than the 50% we found in the trials, especially if the taper is done hyperbolically.

Our full paper has been uploaded as a PRE-PRINT. Also see below.