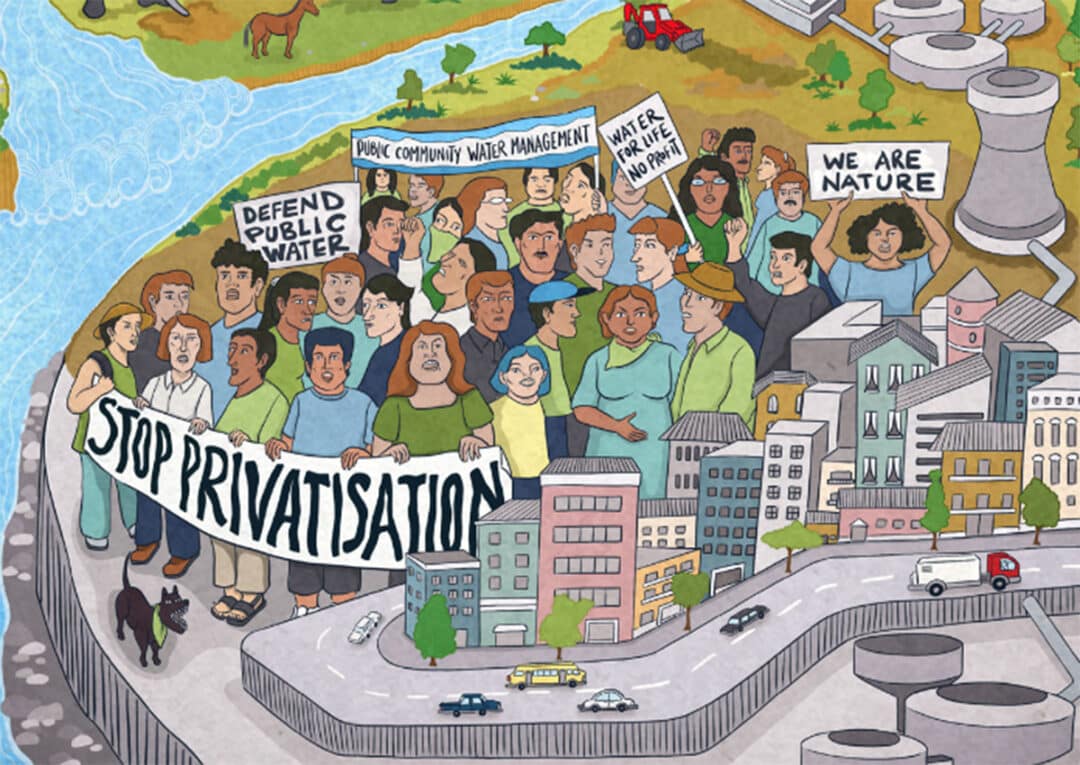

Rivers of resistance: Water for life, not profit

Report by Adrian Murray, Fany Lobos, Javier Márquez | Apr 21, 2023

This report intends to capture the current state of play of the global water justice movement in order to strengthen struggles for public and community water systems. It emerges amid growing water crises in many regions, which have come to constitute a global crisis. It is based on conversations that took place at the “Our Future is Public” conference in Santiago, Chile, in 2022, and is part of the movement’s critical response to- and reflections on the UN 2023 Water Conference.

Introduction

At the end of the last century and the beginning of the present one, movements and organised communities and workers rallied against forces that sought to commodify water, and commercialise and privatise its management and supply. Cochabamba, Bolivia, was the first place where privatisation was reversed, in 2000, and where the privatised company was returned to public hands. In 2004, Uruguay was one of the first countries where the constitution was amended to protect water from privatisation.

Movements from Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe came together in existing spaces and formed new networks to build a global water justice movement to share experiences, stand in solidarity with one another and fight back at the global level. Among other victories, this movement achieved the passing of the United Nations (UN) resolution on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation in July 2010. It also initiated water utility remunicipalisations in numerous countries, bringing supply and sanitation back into public hands, and built alternative visions and mechanisms to support struggles to protect and defend public water.

Over time, the water movement learned that defending public water and returning utilities to public hands was not enough and started to focus on democratising and improving public water services too. Partnerships between community-governed water and sanitation systems and progressive public utilities played a key role in this work, drawing on the expertise and resources of both to strengthen democratic alternatives that manage water ecosystems and services for life, not profit. In the process, a diverse range of water systems, struggles and organisations, including rural, peasant and Indigenous communities, were engaged in broadening, revitalising and expanding the scope of the water movement.

However, water profiteers developed new tactics and strategies to increase private participation in the sector. They have been especially successful in capturing global water governance institutions to advance their pro-privatisation agenda. Today, extractive economic development and climate change threaten water systems globally as billions of people remain without access to safe drinking water and sanitation. Despite the consistent failure of market ‘solutions’, frequently disguised in the language of ‘partnerships’, global water governance and development institutions maintain that the only way to address these challenges is to further privatise and financialise1water in all its forms.

The global water justice movement continues to organise in the face of these threats and to struggle against the growing socio-economic inequalities that restrain access to water on the basis of gender, race and class, among other forms of oppression. These dynamics also differentiate the impacts of climate change and related disasters, most of which involve water and which disproportionately affect those in the South who are both least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and least able to adapt owing to colonialism and imperialism.

The everyday organising work to protect, defend and grow public — community water ecosystems and services for all, is a burden of labour that is overwhelm- ing borne by women.2 The water justice movement centres gender and the care work that also leads and sustains struggles against privatisation and financialisation. Water defenders continue to develop and utilize feminist critiques of these processes and are working to identify and stop the reproduction of gender inequalities within water movements and organisations themselves. This is both the frontline of resistance and the foundation upon which alternatives are built.

From 29 November to 2 December 2022, progressive social movements and organisations from across the world came together, in person and virtually, at the “Our Future is Public” conference in Santiago, Chile, to share, discuss and strengthen struggles for public services and the essential role they play in our societies and must play in our future. After two years of pandemic restrictions, the conference provided the global water justice movement with an opportunity to renew our exchange of experiences and understandings; engage in discussion and debate; raise critical consciousness; build new relationships and reinforce existing alliances; strengthen political momentum around the importance of democratic public water management and services; and revisit the notion of ‘public’ by exploring alternative forms of water management.

This report intends to capture the current state of play of the water movement. It emerges amid growing water crises in many regions which have come to constitute a global crisis. It also comes as the corporate capture of water governance and new forms of privatisation and financialisation intensify, as was on full display at the UN 2023 Water Conference held in March in New York. As these dynamics threaten the vital substance on which all life depends, “we are a flowing river of resistance” which seeks to protect and defend public — community water for all.

In collaboration with

- Platform for Public Community Partnerships of the Americas (PAPC)

- The Catalan Association of Engineering Without Borders (ESF)

- Blue Planet Project

- Corporación Ecológica y Cultural Penca de Sábila

While this report was written and compiled by Adrian Murray with support from Fany Lobos and Javier Márquez, it reflects the perspectives of the water defenders, activists, organisers and researchers present in Santiago and features quotations from their interventions at the Santiago conference throughout.

Illustrator: Paz Ahumada Berríos

Copy editor: Sarah Finch

Designer: Ivan Klisurić / ivanklis.studio

Coordinator: Lavinia Steinfort, Transnational Institute

Subscribe to TransNationalInstitute

Notes and Sources

0 Comments