Hungarian-born US investor and philanthropist George Soros answers questions after delivering a speech on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos on May 24, 2022. (Photo by FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP via Getty Images)

Soros-Funded NGOs Demand Crackdown On Free Speech As Politicians Spread Hate Misinformation

Hatred of racial, religious, and sexual minorities is rising dangerously in Ireland, say the country’s leaders. “Hate-based offenses have become increasingly common in recent years,” said Ireland’s Justice Minister, Helen McEntee, last June. Irish police, she said, have “reported a 29% increase in reported hate crimes in 2022 compared to the previous year.”

However, an increase in the reporting of hate offenses is different from an actual increase. For police to classify something as a hate offense, which is either a crime or “incident,” which is a hate act that is not criminalized, no actual proof or evidence is required beyond somebody simply calling it that. The police themselves admit that the threshold for perception required for this is “very low.”

In fact, you don’t even have to be the victim of the alleged crime to report it. A random bystander who has nothing to do with the event can say, “I think it was based on prejudice,” and it will be categorized as such. Someone could report what was an obvious joke between laughing friends as a “hate incident” to the police.

None of this is to say that Ireland is free from hatred. Certainly, throughout history, the Emerald Isle has had periods of animosity and strife. While it’s certainly true that there is a certain amount of bigotry in Ireland, that’s true of all societies.

But the increase in “hate-based offenses” is clearly from an increase in reporting, not actual hate crimes or “incidents.” Since 2019, the police and the government have openly urged people to come forward and report hate incidents. In 2021, the police said their goal was to “increase levels of reported hate crime.” The idea was that these hate crimes were already occurring, but nobody wanted to report them for some reason — though there is no evidence to support this claim.

And a large body of research finds that people around the world label more things as “harmful” or “hateful” today than they did in the past. Such seems to be the case in Ireland.

The government’s own data shows that Ireland is, ultimately, an unbelievably tolerant country. About 80% of the Irish surveyed recently say they are very comfortable living next door to people with different nationalities, ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations, disabilities, religious beliefs (and none), or marital statuses; 76% of people think the government should help asylum seekers (International Protection applicants); and 72% feel immigrants contribute a lot to Ireland.

As a mixed-race Irish journalist myself who has reported closely on this issue for the last year, I can assure you that there is no good evidence that hate crimes of any kind are increasing in my country, including against people of a migrant background, of which I am one.

Irish people, having lived through centuries of religious strife between Protestants and Catholics, know well what bigotry and ethnic malice can do to society; there is no appetite to return to that in any form. And it’s for good reason that so many foreign visitors tend to think of Ireland as a friendly nation. The country’s national slogan is “Céad Míle Fáilte,” which translates as “A Hundred Thousand Welcomes.”

All of this hype about hate is a pretext for the effort by Irish politicians to pass a strict new “hate speech” law, which would make it a criminal offense to possess allegedly “hateful material” — on paper or digitally — on your person or in your home.

If police raided your home in search of such content and seized your devices, the law would carry a potential penalty of a year in prison and a €5,000 fine if you refused to hand over your passwords to authorities.

In the words of government politicians themselves, the law is designed to “restrict freedom” and to “make it easier to secure prosecutions and convictions.” What’s more, the bill reverses the burden of proof under law — if accused of planning to distribute alleged “hate” material, the onus is on the accused person to prove their own innocence.

Ireland is not only a tolerant society, but it was even a victim of British colonialism and ethnic bias historically itself. A mere generation ago, Ireland endured dire living conditions and pervasive poverty. Rooted in historical struggles, the Irish people often empathize with the challenges faced by colonized populations and marginalized communities abroad.

All this, and yet only 14 TDs (members of the lower house of parliament) voted against it out of 160. The legislation goes to the upper house of parliament in October, which could pass it into law.

Why is that? Why is such a seemingly friendly nation undergoing such an unprecedented assault on its freedom? And what can be done about it?

NGOs and Soros’ “Open Society Foundations”

Minister for Justice Helen McEntee, speaks to the media at Government Buildings in Dublin after the Government said is to amend a Criminal Justice Bill to better support victims of stalking and other sensitive crimes. Picture date: Wednesday June 14, 2023. (Photo by Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images)

In 2021, the Scottish government made “stirring up hatred” a criminal offense. Its sweeping law, which comes into effect next year, even criminalized hate speech at the dinner table in people’s homes.

An NGO called “The Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights” (CRER) was the driving force behind the legislation. It produced a report about online hate speech, and at least one of its employees advocated to the government that it adopt the legislation. CRER went on to advise the government through the Justice Committee that the law should include expansive reporting and should consider “insulting” behavior to be part of “stirring up hatred.”

The Scottish law appears in retrospect to have been a trial run for Ireland. Indeed, the exact same financial source is bankrolling both campaigns: the Open Societies Foundations, created by billionaire financial speculator George Soros.

One of the main groups leading the demand for Ireland’s home hatred censorship legislation is the Irish Network Against Racism. It, like CRER in Scotland, is a branch of the European Network Against Racism, or ENAR. The Open Societies Foundations, which Soros created and funds, donates heavily to ENAR. And NGOs like this have a significant impact on Irish politics when it comes to issues like hate speech laws.

The Republic of Ireland, which has a population of just 5 million people in total, has a whopping 30,000 NGOs, with an annual budget of around €6 billion. For a sense of scale here, Ireland’s entire annual budget is only €103 billion.

As such, these groups wield enormous power and influence within Ireland. They are so numerous and prolific that in 2019, one stunned UN official joked, “No, seriously, is everyone in Ireland in an NGO?” And the government has admitted that many of these groups are involved in “advocacy” and activism.

If you’re an NGO worker who makes your bread and butter on combating “hate,” then Ireland not being a hateful country is an existential problem, and you may soon be out of a job. Think of it this way: if you don’t have leaky pipes, you don’t need a plumber. Likewise, If you don’t have a racist society, you don’t need professional anti-racist campaigners.

Of course, money alone can’t explain why the home hate censorship legislation is moving forward in Ireland. Another part of the problem is the Irish culture of niceness itself. Contrary to the stereotype of “the fighting Irish,” the reality is that Irish people are agreeable by nature due to coming from small rural village communities where everyone has to get along to function day to day.

As such, the Irish are very agreeable. We don’t like to offend others or fall out with our neighbors. And that makes us easy prey for cultural shame stirred up by politicians, state-funded campaign groups, and multinational social media companies.

In an email response to Public, a spokesperson for Open Society Foundations said, “The Open Society Foundations provide general support to the European Network Against Racism. They decide how to invest it and what issues to pursue,” and stressed that they do not support organizations in Ireland or Scotland directly, and do not tell lawmakers what to do.

“In short,” the spokesperson said, “while we appreciate the enormous power to dictate events you ascribe to OSF, your premise reflects a ridiculously reductivist view of how democracies work.”

However, it’s notable that Ireland’s proposed censorship law is aimed at suppressing forms of speech of which the foreign-backed NGO sector disapproves. For instance, the government appears to be taking measures to curtail criticism of the Gender Recognition Bill, which allowed a violent biological male who was guilty of sex crimes to be housed in a women’s prison in Ireland.

Free Speech Lovers Fight Back

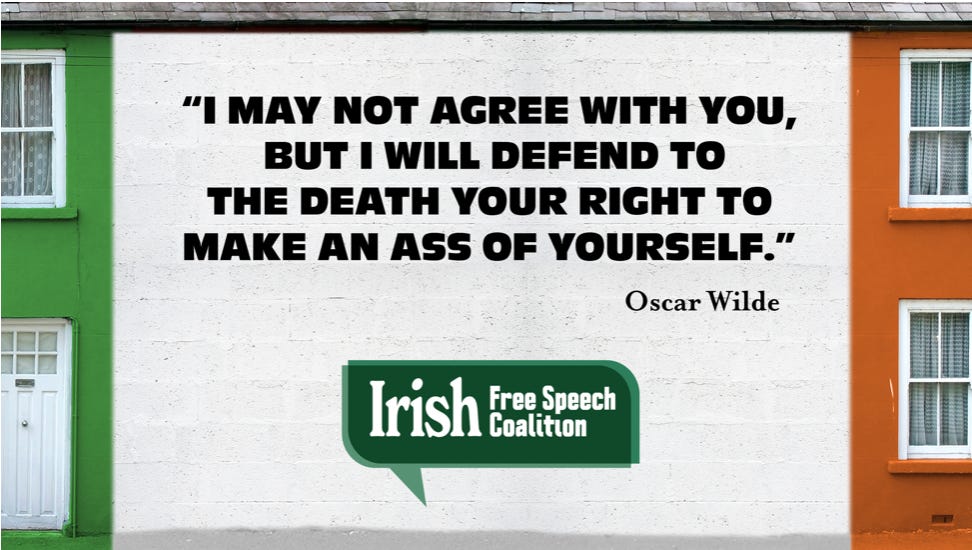

A new ad by the newly formed Irish Free Speech Coalition against the home hate censorship law. (Credit: www.IrishFreeSpeechCoalition.ie)

However, resistance is growing rapidly. After passing to the Seanad (upper house of parliament/Senate), the bill was met with significant controversy and has since stalled until later in the year.

As I was the first to report earlier this year, the government did a series of “public consultations” asking various members of society what they think of such laws, and the vast majority of responses from ordinary citizens were negative towards the idea of hate speech laws. People said emphatically that they didn’t want it.

The government claims it held “consultation exercises,” which garnered positive responses, but they almost exclusively involved State-funded activist NGOs, including — you guessed it — the Irish Network Against Racism. Another consultation received a response from McEntee’s own Justice Department.

The youth wings of both major government parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, both recently called on the government to halt the bill due to the backlash, with one of them even calling on the Justice Minister to resign. Numerous government politicians have said that they have never received this much correspondence about an issue in all their years in politics, making this arguably one of the most controversial pieces of legislation in Irish history.

Socially conservative TD Peadar Tóibín argued that “This Bill is a threat to the democratic function of our society in the long term. The Bill is out of step, in many ways, with the views of people.”

Even some on the Left are against hate censorship. An eco-socialist member of Parliament, TD Paul Murphy, argued that the bill “is the creation of a thought crime.” The Irish Council for Civil Liberties, a civil liberties NGO, has hit out at the fact that the bill’s definitions are not clear enough, claiming that the provision for “freedom of expression” should be more explicit.

And even the spokesperson for the Open Society Foundations claims to be against censorship. “In response to your effort to conflate any attempt to address hate speech as a frontal assault on free speech itself,” said its spokesperson, “perhaps the words of the UN Secretary-General will help in illuminating a crucial distinction: ‘Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech.’”

And now, a new international coalition to protect free speech in Ireland has announced a new website, advertising campaign, and a September event in conjunction with Gript Media and Public to oppose censorship in Ireland. Alex Sheridan, Director of Free Speech Ireland, Public Founder Michael Shellenberger, author Helen Joyce, and I will all speak at it. Our message is not only that hatred is not rising but also that censorship is the wrong response to it. The reason is that censorship prevents people from educating themselves and overcoming their prejudices.

Over time, we believe, public opinion will change to align with the facts. Hatred of racial, religious, and sexual minorities is lower than ever, and there’s no evidence it’s rising. To the extent there’s an increase in hatred, it’s of the elites toward the people they ostensibly represent, and yet want to silence, mostly out of fear.

0 Comments