The Electric Kool-Aid Trump Indictment

by Matt Taibbi | Aug 4, 2023

The United States of America v. Donald J. Trump may be the trippiest read since Cat’s Cradle, and not in a good way.

Special Counsel Jack Smith’s indictment is a case within a case, a prosecutorial enchilada filled with things for people of all political persuasions to hate. The outside is a shell of a conventional conspiracy prosecution, and these parts are genuinely damaging for Donald Trump. Inside, it’s a deranged authoritarian fantasy, at times reading more like a 45-page Louise Mensch tweet than an indictment.

This radical core is somehow scarier than the allegations against Trump and co-conspirators like Rudy Giuliani, John Eastment, Sidney Powell, Jeffrey Clark, and Kenneth Cheeseboro. Despite early criticism describing the case as entirely about protected speech, Special Prosecutor Jack Smith’s case does focus on some overt acts, and these sections are buttressed by witnesses who could be convincing across the spectrum.

Former Arizona Speaker of the House and onetime Trump supporter Rusty Bowers will describe being asked not to certify the results by, among others, Trump and Giuliani. Ronna McDaniel, chair of the RNC, will say she was told votes by so-called “fraudulent electors” would only be deployed if election litigation was successful. Former Vice President Mike Pence, who is rumored to be running for president and took instant advantage of indictment news Tuesday (see below), will testify Trump told him, “You’re too honest,” in response to prods to refuse to certify the outcome.

Today's indictment serves as an important reminder: anyone who puts himself over the Constitution should never be President of the United States.

— Mike Pence (@Mike_Pence) August 2, 2023

If Smith simply focused on those damaging episodes in states like Arizona, Michigan, and Georgia, or on Trump’s interactions with Pence, this prosecution would be an easier sell to the general population. Instead, Smith has tried to pen a Unified Field Theory of insurrection that would massively expand the meaning of concepts like incitement to include false statements, tweets, and other forms of protected speech, down to classic Trumpisms like “I don’t care about a link… I have a much better link,” and “I have a lot of friends in Detroit… Detroit is totally corrupt.”

In fact, if rumors are true and the four counts filed by Smith this week are later complemented by a superseding indictment, this document may end up expanding the definition of “seditious conspiracy” to include those things as well. As Adam Kinzinger said this week, he hoped additional counts will hold Trump “accountable” for all the actions of January 6th.

It’s not hard to read this and see the framework of an argument that Trump’s ideas, tweets and “knowingly false statements” were elements of the same conspiracy to “violently disrupt” the election for which people like Oath Keepers Elmer Stewart Rhodes and Kelly Meggs have already been convicted and sentenced to 18 and 12 years in prison, respectively. A successful prosecution would fold space and time to make legal speech felony violence.

If the “falsifying business records” case in Manhattan involving a payoff to porn star Stormy Daniels felt like one “offense” stretched to 34 counts, Smith’s January 6th indictment seems like 20-30 discrete scenes rolled out as a single conspiracy. In no particular order, here are three bizarre elements of Smith’s vision:

1. The mood police.

-

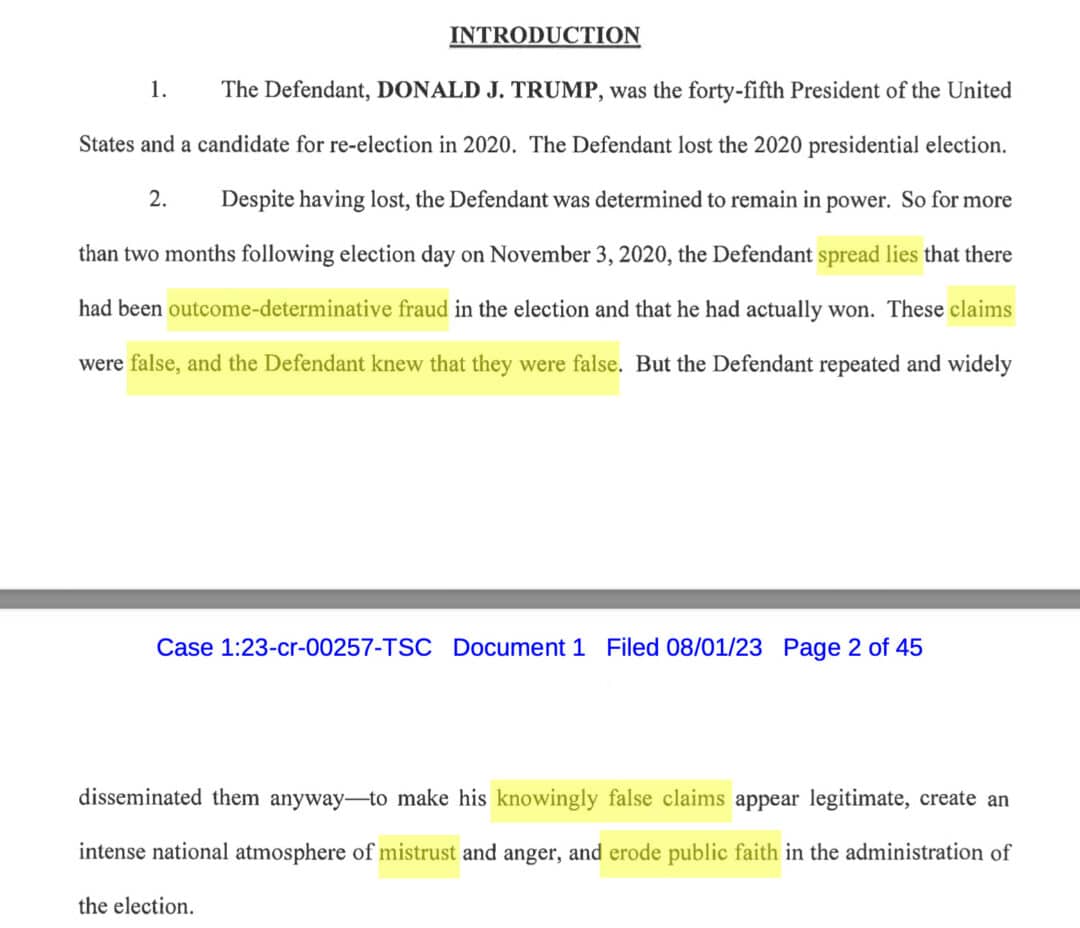

Conspiracy to “create… mistrust and anger.”

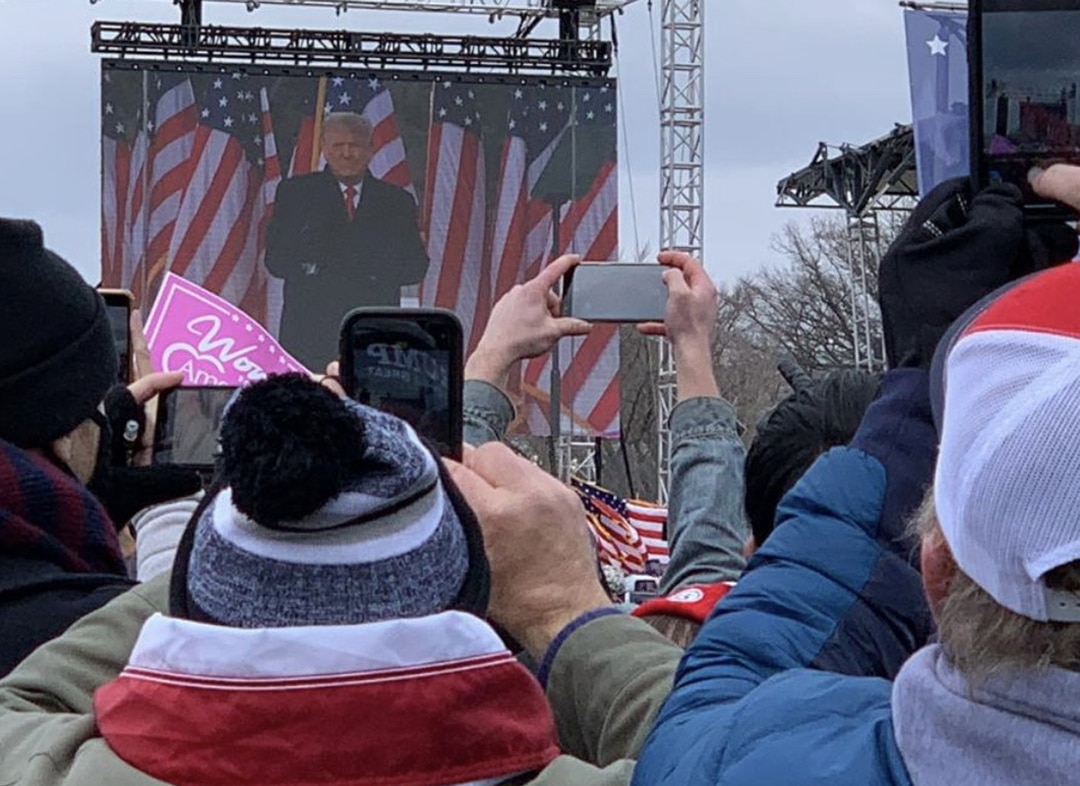

In the opening passages of the indictment Smith rails against Trump’s “knowingly false statements,” saying they created an “intense national atmosphere of mistrust and anger,” intended to “erode public faith in the administration of the election.” I thought I was having an acid flashback when I read this passage. Instead of focusing on overt acts in the individual states, episodes which clearly make even some Trump supporters nervous, the prosecutors are after bigger game. They want to argue that by spreading “lies” Trump created an “atmosphere of mistrust and anger” that, by the end, they will argue led to the “violent” “attack” on the Capitol. This argument brings in fairly anodyne Trump tweets, like “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!”, or “Our country has had enough, they won’t take it anymore!”, and ties it to the crowd’s “Send it Back!” chants, its “steady, violent advancement” toward Capitol doors, and scenes of crowd members “violently attacking law enforcement.”

The Supreme Court in 1969 heard a landmark case, Brandenburg v. Ohio, that set an extremely high bar for government intervention in speech cases, making the standard “likely to incite or produce… imminent lawless action.” A tweeting campaign that begins in November and produces a general “atmosphere of mistrust and anger” that by January works a protesting crowd into a lather is exactly the kind of behavior Brandenburg says is not illegal. In fact, Brandenburg goes further and says “mere advocacy” of the use of force, even advocacy of the forcible overthrow of government, is not illegal. The speech has to be likely to produce “imminent” lawless action to be considered illegal. But Smith wants to criminalize the creation of the “atmosphere of mistrust,” and/or the intent to “erode public faith” in officialdom.

2. The definition of “knowingly false.”

-

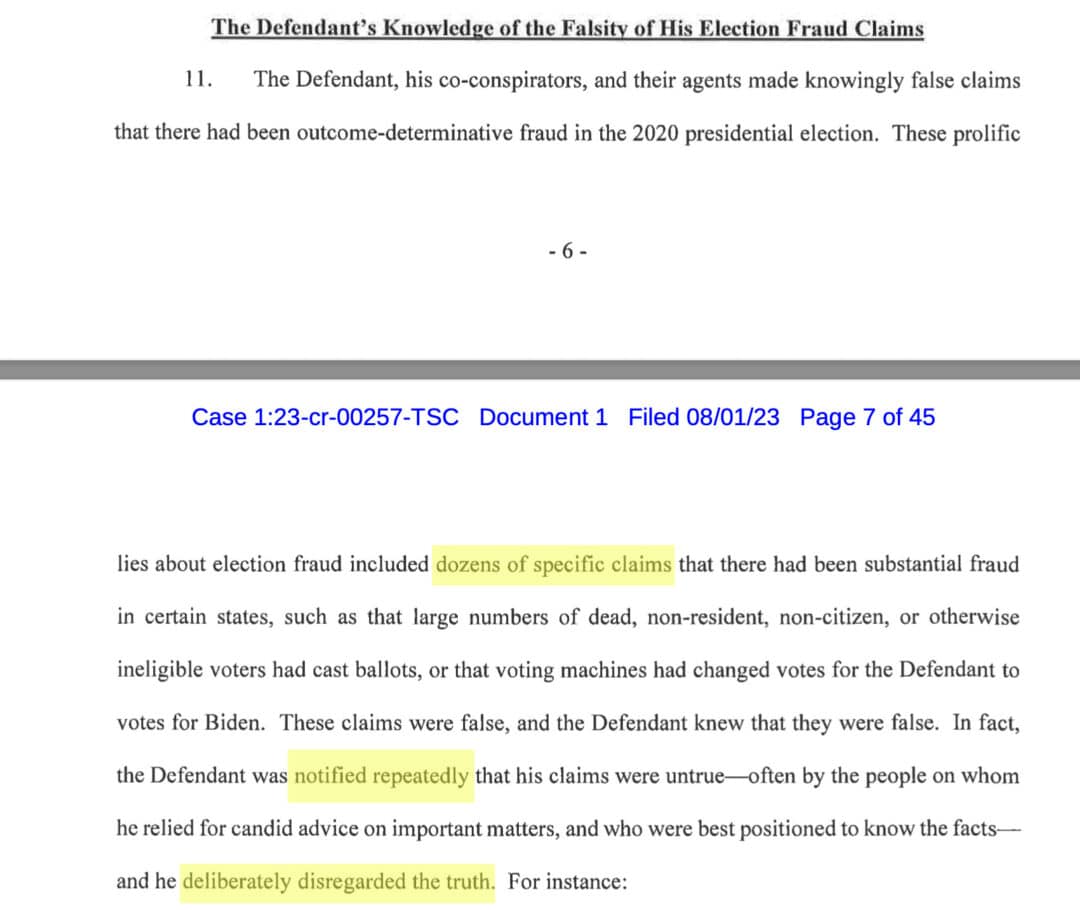

“Best positioned to know the facts.”

In the relentless, redundant style of an MSNBC broadcast or a Washington Post editorial — Smith’s prose in places definitely reads more like moral-clarity-era journalism than law — the prosecutor repeatedly mentions “knowingly false claims.” From a language standpoint alone, it’s wild stuff, like an exercise in how many times one can say the same thing in a handful of lines. In the second paragraph for instance Smith describes how Trump “spread lies” that were “false, and [Trump] knew they were false,” and repeated them even though they were “knowingly false claims.”

Smith in other words makes Trump’s state of mind central to the indictment. Even the New York Times markup of the document notes that “proving Mr. Trump’s mindset may be a key element to all the charges.” Therefore the craziest part of this document is the section beginning on page 6, called “The Defendant’s Knowledge of the Falsity of His Election Fraud Claims.”

One would expect that proof Trump was “knowingly” lying and didn’t really believe the election had been stolen from him would be something like an email to Giuliani saying, “I know this is bull, but let’s try it anyway!”, or testimony from a confederate that Trump admitted in private that he knew he lost. There are bits and pieces of this kind of argument in the text, but Smith leads with a different argument: that Trump had been “notified repeatedly” by people who were “best positioned to know the facts” yet “deliberately disregarded” what he’d been told.

Smith then goes on to list these “best positioned” people: Pence, “senior leaders of the Justice Department,” the Director of National Intelligence, the “Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency” (CISA), “senior White House attorneys,” and others.

Smith is going to try to define “knowingly false” as a statement made in defiance of what one has been told by people “best positioned” to know the facts. Once you’ve been told X by the right people, going on to insist Y anyway will be defined as a “knowing” falsehood.

This concept is deployed over and over. In another section, Trump cites the infamous “State Farm Arena” video, which his team insisted showed evidence of vote fraud in Atlanta. However, Smith says, “Justice Officials specifically refuted” the video, telling them what they were looking at was “benign.” Which may be true, but this is how Smith is trying to prove state of mind: your claim has been “specifically refuted,” you persisted in saying it, therefore it’s a knowing falsehood. Unless I’m missing something, they’re aiming to prove intent without introducing evidence of Trump’s thoughts, which seems bananas.

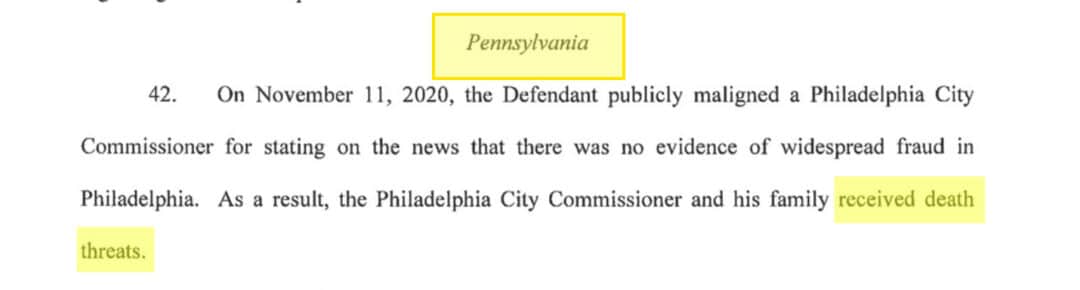

- Trial by “harm.”

“As a result… threats.” After Trump “maligned a Philadelphia City Commissioner” for stating there was no evidence of fraud, Smith noted that “as a result, the Philadelphia City Commissioner and his family received death threats.” There are two of these passages, and Smith seemingly doesn’t feel the need to prove causation in either, using this “Trump said things and as a result threats happened” without listing how the one affected the other, or showing that Trump knew his speech would result in threats, etc.

This goes back to the first problem, redefining incitement as something generalized and broad. Again, in Brandenburg, the court specifically ruled that lines like “Bury the n—” couldn’t be construed as incitement, yet here’s Smith arguing that Trump mean-tweeting former Philadelphia City Commissioner Al Schmidt by saying he was “being used big time by the fake news media” was an element of a crime because threats resulted.

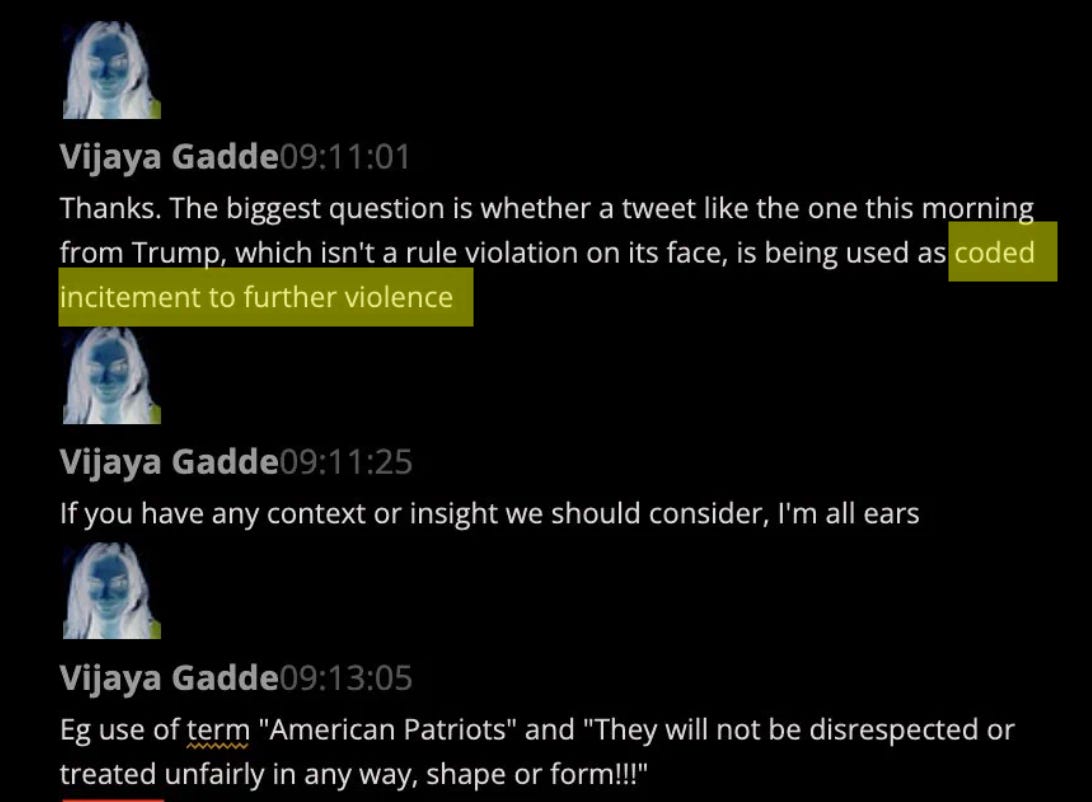

This is very similar to the logic we saw in the Twitter Files, when executives at the company formerly known as Twitter decided that while individual Trump tweets on January 6th weren’t violative, they could be struck under a new definition of incitement that included the so-called “context surrounding.” Bari Weiss showed that executives using this theory could look at the entire history of Trump statements, the reactions to the same, and conclude that phrases like “American Patriots” or “They will not be disrespected” could be understood as “coded incitement to violence.”

- How Twitter made Trump’s tweets “violative.”

Smith is doing the same thing. He’s taking statements that weren’t even against Twitter’s terms of service and arguing they’re part of a criminal conspiracy, using the same thinking that Twitter deployed in creating “coded incitement.” Instead of drawing the most specific, clearest of lines to describe incitement — “Go hit that dude with a rock” — this crop of prosecutors wants to create the broadest definition possible, holding Trump responsible for an “atmosphere” of “anger” that at best arguably inspires violent crowd behavior weeks or months later.

A future superseding indictment could link Trump’s felony case to the seditious conspiracy convictions already handed down. Those cases, if you go back and look, introduced as evidence that the Oath Keepers used “encrypted communications applications like Signal.” So false statements, private gatherings, and words that “erode” trust in government could end up defined as elements of felony conspiracy, maybe even sedition. That’s a concept that would make John Adams or Mitchell Palmer blush.

This prosecution puts Americans in the same conundrum they’ve been in since the beginning of the Trump years: forced once again to choose between a serial line-crosser and more or less open gangster on one hand, and a gang of never-Trump lawfare aficionados who’d like to revive the Alien and Sedition Acts on the other. As Woody Allen put it, “Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.” Are you excited yet?

0 Comments