The Extraordinary Life of Simona Kossak

by Janusz R. Kowalczyk, translated by Paulina Schlosser | Jul 2015

They called her a witch, because she chatted with animals and owned a terrorist-crow, known for stealing gold and attacking bicyclists. A lynx slept in her bed, and she shared her roof with a tamed boar. Simona Kossak was a scientist, ecologist and the author of award-winning films – as well as an activist who fought to protect Europe’s oldest forest.

She was the great-granddaughter of Juliusz Kossak, the granddaughter of Wojciech Kossak, and the daughter of Jerzy Kossak – three painters who loved both Polish landscapes and history. She was also a niece of Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska and Magdalena Samozwaniec. Simona was meant to be a son and the fourth Kossak – carrying easels and carrying on her famous surname.

Instead, she spent more than 30 years in a wooden hut in the Białowieża Forest – without electricity or access to running water. Simona believed that life ought to be simple and close to nature. Living amongst animals, she found something that she never could with her fellow humans.

Elżbieta Kossak – Simona’s mother

Elżbieta Kossak, Simona’s mother, photo: courtesy of the Kossak family archives

Elżbieta Dzięciołowska-Śmiałowska, Simona’s mother, was her future husband’s mistress before she became his bride. Her affair with Jerzy Kossak developed for years. Kossak, already married to Ewa Kossakowa nee Kaplińska, became involved with Elżbieta, 24 years his junior, in the mid-1930s. It was assumed to be an affair between a teacher and his student, between a boss and his assistant.

Jerzy Kossak’s paintings reveal the story of this affair. In 1935, Simona’s future father painted a portrait of Elżbieta’s father, Wiktor Dzięciołowski. He signed the painting ‘For the lovely Elusieńka, in memory of her Beloved Father’. He used either the diminutive Elusieńka, or Elżunienka – it is not easy to decipher which today. In the mid 1930s, then, Jerzy and Elżbieta clearly not only knew each other but also liked each other. In 1937, Kossak painted a canvas based on motives from Adam Mickiewicz’s Ucieczka (The Flight). A horseback rider holds a naked woman, whose features resemble those of Elżbieta, and a signature reads: ‘To the very loved Bubuś on her patron’s day’. Bubuś (and Bobuś) were the nicknames by which Jerzy would later call Elżbieta when she became his wife.

Jerzy Kossak, Simona’s father

Jerzy Kossak, the father of Simona, adored horses, photo: Kossak family archives

How did Jerzy impress Elżbieta? Was it his name? Or was she looking for a father figure in a man significantly older than her? He certainly didn’t lure her with money – the Kossaks were largely indebted at the time – or his looks, as Jerzy didn’t inherit much of his father’s handsomeness. But she ‘loved him like crazy’, according to the claims of their granddaughter, Joanna Kossak, the child of Gloria and Simona’s niece.

By becoming involved with Kossak, Elżbieta wanted to make history – this was Kraków’s open secret. Simona said the following words about her parents’ marriage:

My mother was so in love with my father that everything that belonged to him or was his, automatically became hers. […] They knew each other for a long time; mother had time to become acquainted with father’s tastes and she took them as her own. She embodied the whole household and tradition that reigns in Kossakówka.

Dziedzinka – either here or nowhere

‘Simona, we’re going to Dziedzinka, maybe you will like it there’ – they went, and Simona loved the place instantly, for over 30 years, she lived in the hut in the middle of the Białowieża Forest, photo: Lech Wilczek

‘Simona first saw Dziedzinka in moonlight’, Ewa Wysmułek remembers:

We decided we would go there at night time. The four of us went down the road with torches: my husband, a hired carter, myself and Simona. Suddenly, a wisent stepped out onto Browska Road. The horse jibbed; we got scared, but we got there. Simona was enchanted with Dziedzinka straight away.

Years later, Simona described the expedition and the encounter with the king of the forest in the following words:

It was the first wisent that I saw in my life – I am not counting the ones in the zoo. Well, and this greeting right at the entry into the forest – this monumental wisent, the whiteness, the snow, the full moon, whitest white everywhere, pretty […] and the little hut hidden in the little clearing all covered with snow, an abandoned house that no one had lived in for two years. In the middle room, there were no floors; it was generally in ruins. And I looked at this house, all silvered by the moon as it was, romantic, and I said, ‘it’s finished, it’s here or nowhere else!‘

Kossakówka in Dziedzinka

Simona decorated the interiors of the Dziedzinka den with souvenirs from the familial Kossakówka, photo: Lech Wilczek

Before Simona went to live in Dziedzinka, the house had to be renovated. The employees of the Białowieża National Park repaired the roof, changed the joists, got rid of the fungus, and said that ought to suffice for five years (and indeed it did). After the renovations, Simona started to arrange her part of Dziedzinka. She plastered the walls with wallpaper, washed the windows, placed the sofa and bench, and upholstered the armchairs that were brought over from Kraków.

She brought clocks from Kossakówka, as well as a Turkish dagger, a lace tablecloth and window curtains, books, oil lamps, an antique iron, a collection of weapons, ebony jewellery chests, as well as glassware, porcelain, cupboards and an oak bed that she inherited from Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska. Right by the door, she hung a shotgun from the Kossaks’ collection. And she didn’t care when Jacek Wysmułek said to her: ‘You won’t make a Kossakówka out of Dziedzinka’.

A large tile stove in the old style stood in the corner of Simona’s room, and a large table was placed in its middle – it was her workshop study, where she worked by an oil lamp. All the furniture, tablecloths and books came from Kossakówka with Elżbieta Kossak, who came to stay with her daughter. In the summer, Simona divided her own part of the Dziedzinka from that of her mother with a curtain.

‘A phenomenon advancing on the “mosquito”’, aka Simona Kossak on her way to the Dziedzinka hut, photo: Lech Wilczek

The first Kossak rode on horseback and in a carriage; the second rode on horseback, in a carriage, and in an automobile; and the third used the same means of transport as his ancestors. Simona rode a bicycle, the ‘komar’ motorbike [the nickname literally means ‘mosquito’], a small Fiat aka Maluch, an all-terrain vehicle, a tractor, and she also swept through the landscape on cross-country skis. She covered the trail from Białowieża to Dziedzinka hundreds of times on all these vehicles. The route which some monikered the ‘Paris-Dakar Rally’ was filled with mud, and it was regularly demolished by cars which carried out oak wood from the forest.

Tomasz Werkowski, a hunter from Białowieża, recalls: ‘Once I saw this phenomenon advancing on a komar – wind in the hair, a pilot-cap, rabbit pants, and eye goggles. It passed me by and I had to turn around, because I didn’t know what it was. This was in 1974, the very first time that I saw Simonka’. A couple of private vehicles had already started to appear in Białowieża at this time, but none of them belonged to Simona. In the winter, she rode her komar to work, with her hands freezing to the handles. Professor Kajetan Perzowski, a colleague of Simona from her university years in Kraków, says:

Once, with a friend, I was going across the Białowieża Forest in a small truck. Suddenly, we see someone pushing through the snowdrifts carrying a motorbike on their back. It was Simona. We packed her together with this motorbike onto our truck. She thanked us later, heating up a big pot of bigos at Dziedzinka.

Cuddler

A common meal in the company of a particular household member – Simona with the sow Żabka, photo: Lech Wilczek

The boar, a one-day old female, was brought by Lech Wilczek, and it was thanks to this animal that the two dwellers of Dziedzinka – Simona and Lech – go to know each other better. And they also came to like each other. Prior to this event, Simona thought Lech was too full of himself. He also had a similar opinion about her. When the boar appeared in Dziedzinka, Wilczek asked Simona to take care of her in his absence, and later he started to ‘lend’ the animal out to her. Both later started to sleep with the little boar in their beds.

Żabka grew to become an XXL-sized boar, and she lived with them for 17 years. ‘She stood vigilantly by the leg like a dog, she went out on walks, and more and more often she cuddled up to the hosts and demanded to be caressed!‘, exclaimed Zbigniew Święch, the Kraków-based journalist and a guest of Dziedzinka.

Simona with the crow Korasek, who would steal gold and attack bicycle riders, photo: Lech Wilczek

People called the crow a tamed villain and a thief. He terrorised half of the Białowieża area. He stole cigarette cases, hair brushes, scissors, cutters, mouse traps and notepads. He attacked people. […] He tore up bicycle seats. He stole documents, he stole lumberjacks’ sausages in the woods, and made holes in grocery bags. He clung at men’s pant legs, pulled at women’s skirts, and pricked their legs. People thought that Korasek – because that’s what he was called – was some kind of a punishment for their sins.

Stanisław Myśliński, who has scars from the bird to this day, recalls:

He would even steal workers’ pay in the woods. He once stole my permit for entering the woods. He pulled it out of my pocket and notoriously tore it apart. He loved to attack people who rode bicycles, especially girls. It was very impressive – he would attack the rider’s head with his beak, the person would fall off, and he then would sit on the seat triumphantly, looking the at the spinning wheel.

Simona’s friend says:

Once he stole my car keys. And Lech [Wilczek] said: ‘Don’t worry, he’ll bring them back’. He took a metal rod and scared the crow: ‘You sonofabitch, you took keys from a friend?!’ He and I said to Korasek that if he brings them back, he’ll get an egg, and if he doesn’t, he’ll get a blow with the rod. And the crow perhaps understood this, because after a moment, he flew up to me, furious, with the keys in his beak and threw them onto a table!

Bożena Wajda recalls:

Once, I was walking around the reserve without a permit, and the guard saw me, he followed me to Dziedzinka and started to fill in a fine penalty. When he was handing the print to me, the crow appeared. He took the paper in his beak, flew onto the roof of Dziedzinka with it, and tore it up with his leg, on top of that roof. I had such a laughing attack that I couldn’t control myself, the guard didn’t know what to do, and finally, he just shrugged his shoulders at the whole thing. When I told this story to Simona, I thought she would die of laughter.

The spirit of landownership

Elżbieta Kossak, Simona’s other, liked the life in Dziedzinka – for two years, she travelled between Kraków and Białowieża, photo: Lech Wilczek

Simona’s mother, Elżbieta, travelled between Kraków and Białowieża for two years. For the winter, she would return to the hut in Kossakówka. She had problems with her hip and walked with crutches, and moving about Dziedzinka, where the outdoor privy was a huge challenge. But for this woman, brought up in the tradition of landownership, Dziedzinka must have been a true paradise – life in accordance with the rhythm of nature, frying jams, and five o’clock tea. Life on Dziedzinka did resemble an atmosphere of a manor in the summer. There was reading by the light of oil lamps, keeping hens, and with time, also spinning wool. On top of that, the chime clocks from Lech Wilczek’s collection resounded every hour.

Simona now lived not unlike her grandmother, Mrs Wojciech Kossak, and probably much like her own mother in her childhood years. Just like them, she also used herbs for medicine and used the words such ‘subiekt’ [subject] and ‘etażerka’ [meaning both a whatnot and a rack]. And just like her mother and grandmother, she paid attention to what kind of company she surrounded herself with. In conversation, she also used the ‘esprit de répartie’ – witty riposte – in which she was trained since her early years, like every landowner’s child. And first and foremost, she did not consume her life, but rather treated it as a task, and at times – as a mission.

A member of the pack

Simona with a pack of deer, photo: Lech Wilczek

Simona recalled:

One day, the pack of my deer, which I raised and fed with a bottle, and which I later followed across the woods for many years, manifested signs of fright, and did not want to go out onto the forest field to graze. And I started to approach the young forest, because this was the direction in which the deer started, their ears raised, and the hair standing up on their buttocks, apparently something very threatening had to be there in the young forest. I crossed about half of this open space, and I stopped, because I heard a choir of terrified barking behind me, so I turned around, and what did I see? […] Five of my deer stood up on their stiffly straightened legs, looking at me, and calling with this bark: don’t go there, don’t go there, there’s death over there! I must admit, I was dumbstruck, and then finally I did go. And what did I find? It turned out that there were fresh traces of a lynx that had crossed the young forest. I went in deeper, and I found lynx faeces; it was indeed warm, because I touched it. What did that mean? It meant that a carnivore had entered the farm, the deer noticed him, then ran and they were scared, and what did they see? They saw their mother going unto death, completely unaware, she had to be warned, and for me, I will honestly admit, this day was a breakthrough. I crossed the border that divides the human world from that of the animals. If there was a glass that divided us from humans, a wall impossible to knock down, then the animals would not care about me. We are deer, she is human, what do we care for her? If they did warn me […], it meant one thing and one thing only: you are a member of our pack, we don’t want you to get hurt. I honestly admit, I relived this event for many days, and in fact today, when I think about it, there is sense of warmth around my heart. It proves how one can befriend the world of wild animals.

Zoo-psychologist

For the animals, she was like a mother – Simona with the twin moose, whom she called Cola and Pepsi, photo: Lech Wilczek

With time, more animals appeared in Simona’s den by the house: a doe who approached the window and ate sugar, a black stork for whom Simona created a nest in a chest in her room, a dachshund and a female lynx that slept in the same bed with Simona, as well as peacocks. Dziedzinka quickly became an experimental laboratory which Simona consequently expanded as a zoo psychologist – with a hospital and a waiting room for sick animals.

Here, she healed, hugged, and observed the animal lot together with Wilczek, who photographed them. Here, as a mother she raised moose twins, Pepsi and Cola, washed the neck of the black stork, took the female rat Kanalia into her sleeve (as the animal panicked in open spaces). She let the befriended doe give birth on the patio, took in lambs with their mother, kept and observed the rats Alfa and Omega, and keep crickets in a glass container. It was here that she checked on the weather by observing bats in the basement. The menagerie grew with each year.

The battle for lynxes and wolves

Simona with the female lynx Agata, kept for the film by Jan Walencik. photo: Lech Wilczek

In the winter of 1993, Simona commenced her battle for saving the lynxes and wolves of Białowieża from perdition. In an article for Twój Styl (Your Style) magazine, Alina Niedzielska wrote, for example, that:

A group of young workers from the Mammal Research Plant of the PAN Polish Academy of Sciences came up with the idea of telemetric studies. A wild animal is given a collar with a radio transmitter, so that it would pass out information as it walks about the woods. But the carnivore must first be caught. By coincidence, it was revealed that the researchers set up traps for the wolves and lynxes, which are prohibited by Polish law. Simona Kossak shows the ‘research apparatus’ that she came across in the forest – heavy metal jaws. It takes two men to open them up. She had just put away a ready typescript when a pack of wolves approached the house. […] The wolves howled terribly. […] ‘It was a gratuitous hymn for saving their lives’, she commented with conviction. ‘Wolves never approach buildings. They are too frightful. Perhaps they sensed the friendly aura emanating from the hut’.

In 1993, within the strict natural reserve territory, Simona came across two metal jaw traps put up by the Mammal Research Plant team, so she took them with her and refused to give them back. She was accused by the scientist of stealing the research apparatus. The matter was investigated by the Regional Prosecution in Hojnówka and the 2nd Criminal Section of the Regional Court in Bielsko Podlaskie. During the hearing conducted by the Prosecution, in response to the question what kind of a threat such research apparatus in the Białowieża Forest presented to animals, Simona answered:

In my opinion, it was a lethal threat not only to the animals, but also the guards. […] Each animal that falls into the trap is potentially condemned to die, if the wound to the paws is heavy. With a population that numbers 12 specimen, and including poaching and chance deaths of wild animals, it is a lethal threat to the continuity of the lowland lynx type, whose genetic scope is unique across all of Europe, because there are no more lowland lynxes in Europe. It is a disgrace to the world of science for us to have contributed to this.

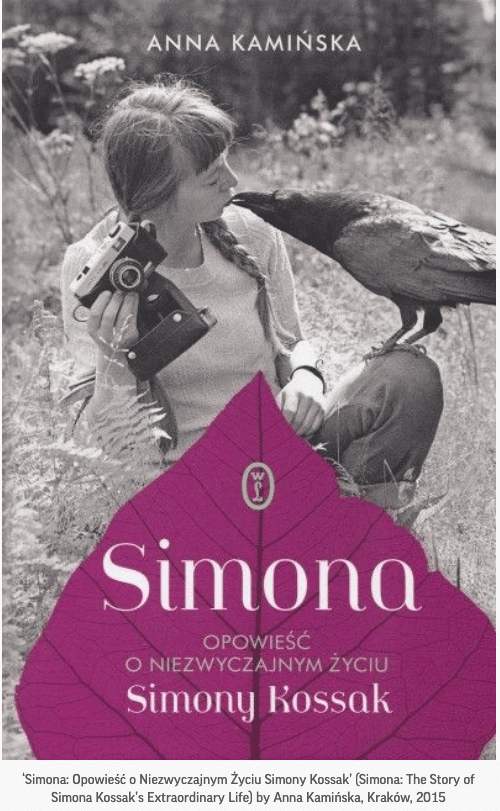

Anna Kamińska is a journalist, an author of books, and a television publisher. She has written for the Wysokie Obcasy (Gazeta Wyborcza) weekly, as well as magazines such as Uroda Życia, Zwierciadło, Sukces and Pani. The author of Odnalezieni: Prawdziwe Historie Adoptowanych (The Re-found: True Stories of the Adopted, 2010), Miastowi: Slow Food i Aronia Losu (Cityfolk: Slow Food and the Aronia of Fate, 2011) and the biography Simona: Opowieść o Niezwyczajnym Życiu Simony Kossak” (Simona: The Story of Simona Kossak’s Extraordinary Life, 2015). In her free time from writing, Kamińska plays the cello.

Anna Kamińska is a journalist, an author of books, and a television publisher. She has written for the Wysokie Obcasy (Gazeta Wyborcza) weekly, as well as magazines such as Uroda Życia, Zwierciadło, Sukces and Pani. The author of Odnalezieni: Prawdziwe Historie Adoptowanych (The Re-found: True Stories of the Adopted, 2010), Miastowi: Slow Food i Aronia Losu (Cityfolk: Slow Food and the Aronia of Fate, 2011) and the biography Simona: Opowieść o Niezwyczajnym Życiu Simony Kossak” (Simona: The Story of Simona Kossak’s Extraordinary Life, 2015). In her free time from writing, Kamińska plays the cello.

0 Comments