The false red flag: industrial slavery

by Paul Cudenec | Apr 1, 2024

Leo Tolstoy, with his dreams of a free Russian peasantry, had realised before his death in 1910 that the communists aimed to launch an assault on traditional rural life.

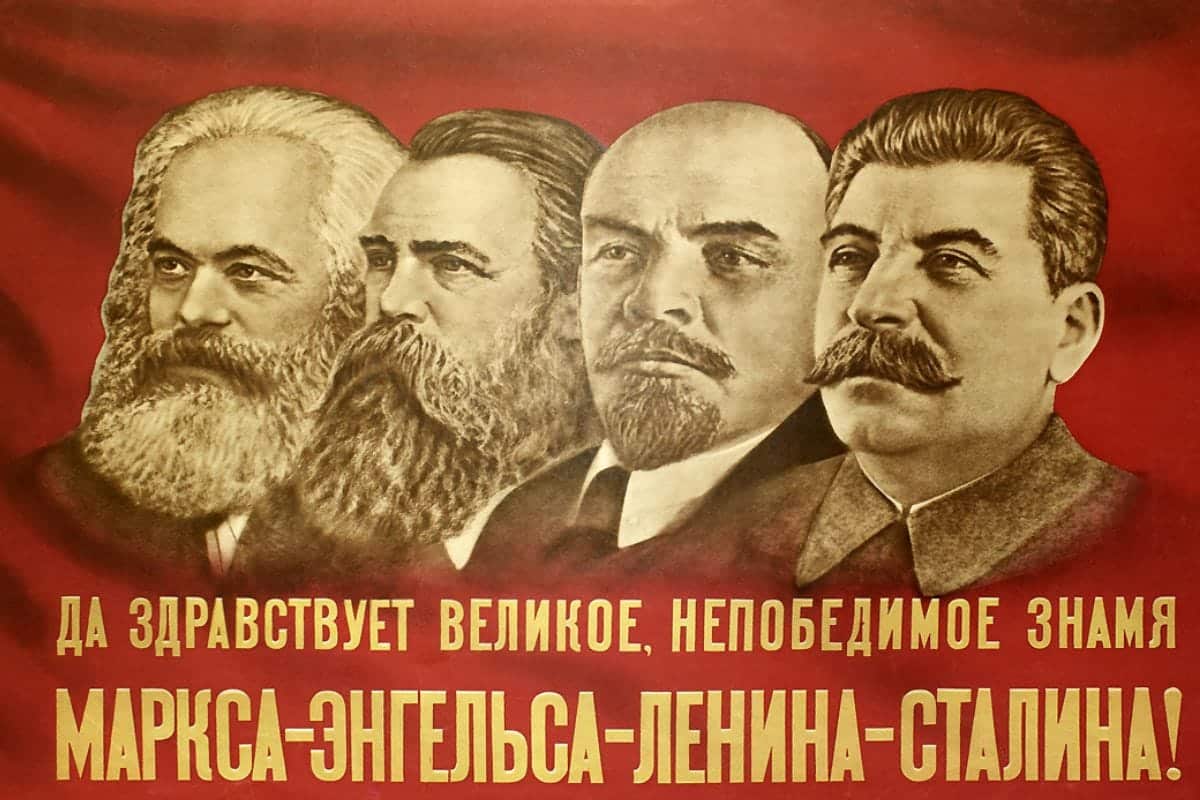

Having analysed Karl Marx’s Capital and studied the new “scientific” socialism, he spoke out about what Pierre Thiesset calls the communists’ “industrialised, urbanised and technocratised horizon, where Progress becomes a new religion”. [45]

“He had felt that the revolutionaries were going to fool the people by leading them into a dead end: that of the modernisation of the country and the end of the peasantry.

“What is the point in socialising the means of production if it is to proletarianise the population, to send modern slaves to live in filthy cities and become appendages of machines?

“The writer called on people to resist this development, to struggle against this so-called ‘civilization’.” [46]

This, of course, made Tolstoy a “reactionary” in the eyes of the Bolsheviks, while those who supported his call for land and freedom were labelled “naive” and “retrograde”. [47]

Vladimir Lenin, while recognising that Tolstoy (pictured) was a spokesman for the ideas and desires of millions of Russian peasants, declared that his ideas were, as a whole, “harmful”. [48]

He announced, 15 years before his party came to power: “This patriarchal peasantry, which lives from its own work under the system of the natural economy, is condemned to disappear”. [49]

Even earlier, in 1899, Lenin had written a book called The Development of Capitalism in Russia [50] in which he described the mobility of the workforce and the extension of the market as representing “progress”.

He rejected the idea that the rural commune could serve as the basis for communism and that Russia could take an alternative path that avoided Western-style industrial development.

And he stressed the need to sweep away all the outmoded institutions that impeded the development of capitalism, that supposedly necessary stage on the road to socialism. [51]

When the communists finally grabbed power, they were true to their word and, under Lenin and then Stalin, declared war on the Russian peasantry.

Writes Carroll Quigley: “Communism in Russia alone required, according to Bolshevik thinkers, that the country must be industrialized with breakneck speed, whatever the waste and hardships, and must emphasize heavy industry and armaments, rather than rising standards of living.

“This meant that the goods produced by the peasants must be taken from them, by political duress, without any economic return, and that the ultimate in authoritarian terror must be used to prevent the peasants from reducing their level of production to their own consumption needs”. [52]

He says: “The high speed of industrialisation in the period 1926-1940 was achieved by a merciless oppression of the rural community in which millions of peasants lost their lives”. [53]

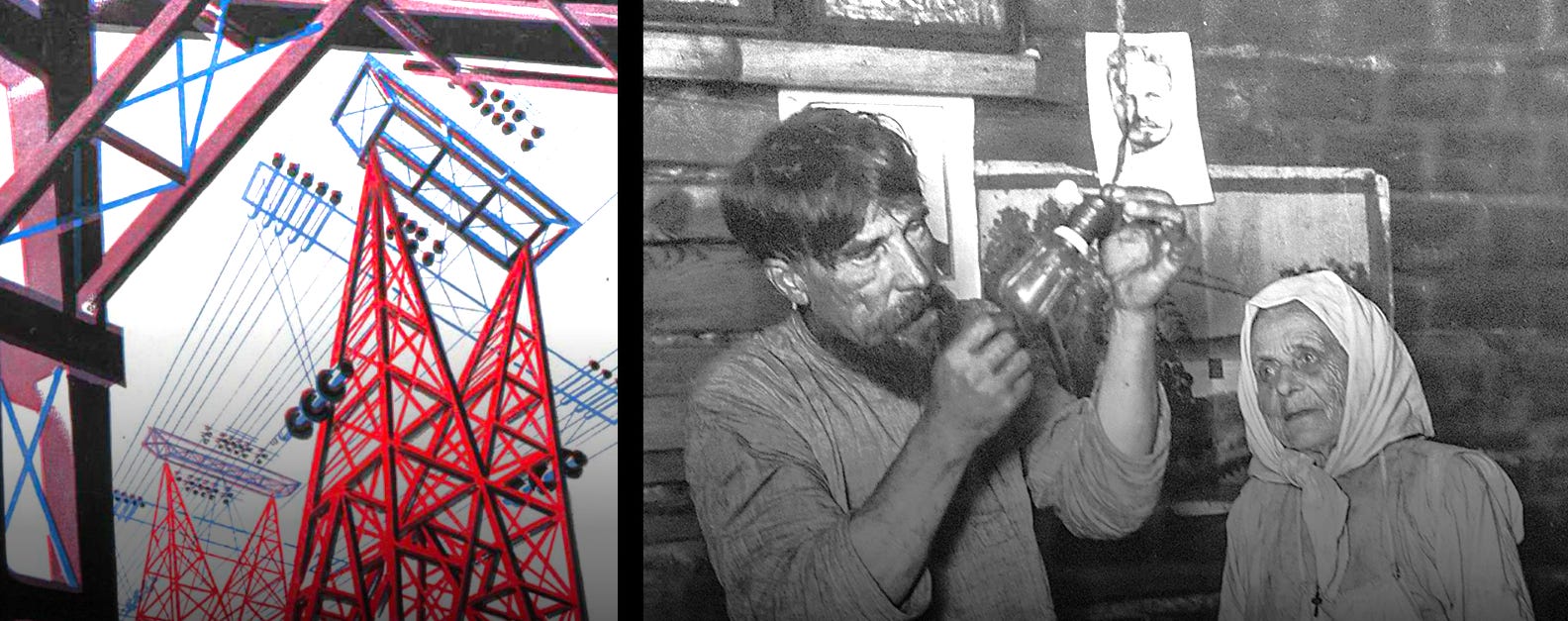

“The chief elements in the First Five-Year Plan were the collectivization of agriculture and the creation of a basic system of heavy industry. In order to increase the supply of food and industrial labour in the cities, Stalin forced the peasants off their own lands (worked by their own animals and their own tools) onto large communal farms, worked co-operatively with lands, tools, and animals owned in common, or onto huge state farms, run as state-owned enterprises by wage-earning employees using lands, tools, and animals owned by the government”. [54]

Agriculture was industrialised by the use of machinery, particularly tractors – the number of these in Russia rose from less than 30,000 in 1928 to nearly half a million in 1938, with the percentage of ploughing done by tractor shooting up from 1 per cent to 72 per cent. [55]

Voline describes how the Russian peasant had his patch of land and his possessions confiscated and was attached to a “kolkhoz” like a worker to a factory.

“The state transformed him not merely into its farmer, but into its serf and forced him to work for this new master.

“And, like any real master, it only leaves him, from the produce of his work, the minimum needed to live: the rest, the largest part, is put at the disposal of the government”. [56]

He comments that this system did not lead “towards socialism” but into state capitalism, “even more abominable than private capitalism” and just “another mode of domination and exploitation”. [57]

It was the same story in communist factories, in which the dehumanising production-boosting Taylorism used in the West was wrapped up in workerist propaganda and rolled out as Stakhanovism. [58]

This was all imposed through the regime’s vicious totalitarian approach, spearheaded by the notorious Cheka secret police.

Some of the Kronstadt rebels were already warning in 1921: “A new – communist – serfdom has been established. The peasant has been transformed into a serf of the ‘Soviet’ economy. The worker has become a simple employee in the state’s factories. The working class intelligentsia has been virtually wiped out.

“Those who wanted to protest have been thrown into the Cheka’s jails. And those who continued to agitate were simply put up against the wall. The whole of Russia has been turned into a huge penal colony”. [59]

Quigley writes: “By the middle 1930’s the search for ‘saboteurs’ and for ‘enemies of the state’ became an all-enveloping mania which left hardly a family untouched.

“Hundreds of thousands were killed, frequently on completely false charges, while millions were arrested and exiled to Siberia or put into huge slave-labor camps.

“In these camps, under conditions of semi-starvation and incredible cruelty, millions toiled in mines, in logging camps in the Arctic, or building new railroads, new canals, or new cities”. [60]

He says that most of these gulag prisoners had not even done anything against the Soviet state or the communist system, but were the relatives, associates and friends of persons who had been arrested on more serious charges.

And he adds that many of these charges were completely false, having been trumped up “to provide labour in remote areas”, [61] among other reasons.

The communist regime effectively amounted, as Voline spells out, to a “totalitarian capitalist state”. [62]

Its society was characterised by “a stifling dogmatism”, the absence of all real individual life and “the despairing monotony of a glum and colourless existence, regulated in the smallest detail by the prescriptions of the state”. [63]

Critical thinking and any questioning of the official narrative was utterly out of bounds and children’s heads were stuffed full of rigid Marxist doctrine, he says. [64]

The communists particularly excelled in the field of propaganda or “more exactly of lies, deceit and bluff”. [65]

“Compared to them, the ‘Nazis’ themselves are nothing but modest pupils and imitators”. [66]

“This deceitful propaganda across the world is of unrivalled scope and intensity. Considerable sums have been sacrificed to it”. [67]

The communist state had declared itself the sole judge of truth on every subject – historical, economical, political, social, scientific, philosophical or anything else, he says.

“In all domains the Bolshevik government considered itself infallible and called upon to lead humanity”. [68]

Any person or group who doubted the state’s infallibility, who criticised or contradicted it in any way, was considered to be its enemy, and an enemy of both truth and the Revolution – a “counter-revolutionary”! [69]

Voline adds: “Any opinion, any thought, other than that of the state is considered heresy: dangerous, unacceptable, criminal heresy. And, logically, unavoidably, there follows the punishment for heretics: prison, exile, execution”. [70]

He sums up the Soviet system as “a monstrous and murderous state capitalism, based on an odious exploitation of the ‘mechanised’, blind, unconscious masses’”. [71]

And he wonders why it was that the long-awaited Revolution had resulted only in a “new dictatorship” and “new slavery”. [72]

The next part of this essay will go some way to answering that, along with the key question of why the Bolshevik New Normal of 100 years ago sounds so uncannily similar to the nightmare future towards which we are being herded today.

Subscribe to Paul Cudenec

[45] Thiesset, p. 97.

[46] Thiesset, p. 97.

[47] Thiesset, pp. 94-95.

[48] Lénine, ‘Six études sur Tolstoï’, revue Commune, no 17, janvier 1935, cit. Thiesset, p. 94.

[49] V. Lénine, Oeuvres, tome VI; janvier 1902-août 1903 Editions sociales (Paris) et Editions du Progrès, Moscou, 1966, cit. Thiesset, p. 95.

[50] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Development_of_Capitalism_in_Russia

[51] V. Lénine, Le Développement du capitalisme en Russie (écrit entre 1896 et 1899), Editions en langues étrangères (Moscou) et Editions sociales (Paris), 1956, cit. Thiesset, p. 95.

[52] Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope: A History of The World in Our Time (New York: Macmillan, 1966. Reprint. New Millennium Edition), p. 250.

[53] Quigley, p. 12.

[54] Quigley, p. 251.

[55] Quigley, p. 251.

[56] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 109.

[57] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 110.

[58] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 98.

[59] L’Izvestia du Comité Révolutionnaire Provisoire, No 10, 12 mars 2021, cit. Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, pp. 244-45.

[60] Quigley, p. 254.

[61] Quigley, p. 254.

[62] Voline, la fin de Cronstadt et l’Insurrection en Ukraine, p. 28.

[63] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 150.

[64] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 149.

[65] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 131.

[66] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 131 FN.

[67] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 132.

[68] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 123.

[69] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 124.

[70] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 124.

[71] Voline, du pouvoir bolshéviste à Cronstadt, p. 125.

[72] Voline, de 1905 à Octobre, p. 21.

The first two parts of this essay were Fake resistance and Lies and repression – two further parts will follow:

A repugnant racket

Flawed and despotic

Alternatively, the whole thing can be downloaded as a free pdf booklet here.

0 Comments