The RFK Jr. Tapes

by David Samuels | Apr 24. 2023

The first met Bobby Kennedy Jr. when he showed up one summer afternoon in 1976 at the door of my ordinary suburban home in the company of a friend from Harvard named Peter Shapiro, who was running for a seat in the New Jersey State Assembly. I was 9 years old, and not particularly thrilled about our family’s recent move from Brooklyn to a street of empty suburban lawns whose nearest point of interest was a candy store a mile or so down a steep hill. The two polite, handsome young men in navy blazers, both in their 20s and well over 6 feet tall, promised a whiff of something different.

I don’t recall if I had any idea that the young Bobby Kennedy’s uncle had been president, or that his father had run for president; as a first-generation American, I knew that important people went to Harvard, and being a Kennedy was like being a movie star. The two young men on my doorstep, politely asking if my parents were home, immediately appealed to my imagination as connections to a world that I hadn’t seen before, but which might be fun. So I gladly took them to Tory Corners, the Irish working-class district nearby, and spent the rest of the afternoon handing out buttons and leaflets for the Shapiro for Assembly campaign.

Peter won that race, and a year later, at the age of 26, he ran for the newly created job of Essex County Executive, and he won that race too, becoming something of a rising figure in national Democratic politics—a future Jewish president, even. In 1984, he won the Democratic nomination for governor before losing in a landslide to the popular Republican incumbent Tom Kean, effectively ending his political career. In between, though, I became something of an in-house mascot—the joke being that I was the only person involved in Peter’s campaigns who was younger than the candidate.

For his part, Peter graciously embraced his role as my patron, offering me summer jobs in the County Executive’s office, writing me a letter of recommendation to his alma mater, and hooking me up with a job in Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s office in Washington. The highlight of my employment there was the week when I got the first of what would turn out to be a number of up-close looks at the Kennedy mythos—the week I spent with my friend RJ, a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts, scrubbing the senator’s house in McLean, Virginia, from top to bottom—in preparation for what turned out to be a party celebrating the 20th anniversary of the John F. Kennedy Library. The guest list for the event consisted of the extended Kennedy family, including the late president’s widow, who was remarkably friendly and kind; a few of the senator’s drinking buddies, including Sens. John Tunney and Chris Dodd; House Speaker Tip O’Neill; President Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy; and me and RJ. Having acquainted ourselves with the lay of the land, RJ and I then returned to the senator’s house late one night with two fellow interns and some bottles of Andre sparkling wine and got drunk in his hot tub, an act that the senator would have no doubt got a kick out of. When I call myself a Kennedy Democrat, those are among my reasons.

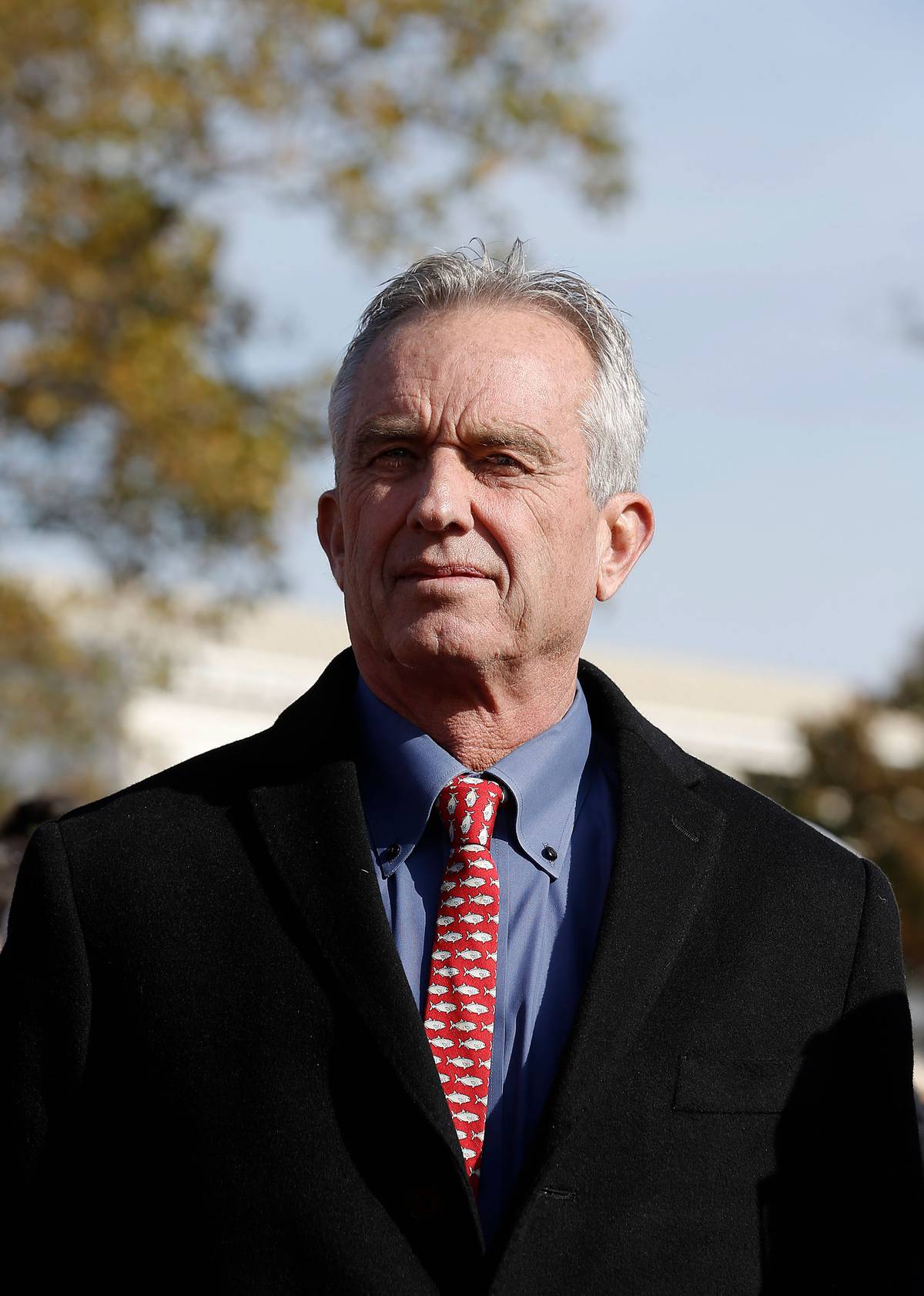

Robert Kennedy Jr. demonstrates during the ‘Fire Drill Friday’ climate change protest in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 15, 2019 John Lamparski/Getty Images

Family patronage and largesse are not what people generally celebrate as the strengths of American democracy these days, though I would venture that the current emphasis on tribal warfare and jailing one’s political foes is in fact an inferior model. I would also suggest that it is an empirical fact that far more significant legislation of far more benefit to poor and working people passed the U.S. Congress in the 1970s and even the 1980s than is ever proposed, let alone passed into law, by the tribunes of TikTok and Fox News. Before it was transformed into an instrument of billionaire oligarchs and their nonprofit bureaucracies and the American security state, the Democratic Party proved itself capable of delivering tangible benefits to tens of millions of ordinary Americans in the places where they lived—whether that meant urban church parishes or the Ozarks. Once upon a time, the Democratic Party aimed to make the lives of ordinary people better, by working through the institutions that they built and valued, rather than subjecting them to tedious lectures about right-think and using the government as an instrument to punish anyone who said the wrong words the wrong way. The party’s message was that everyone could find a welcoming place under its roof, and have their foundational beliefs honored and respected—the job of the Kennedy family being to sprinkle some handfuls of fairy dust over the whole affair. It was a job that the family took seriously for decades, sending their children to spend summers in Africa or Appalachia, or helping out with the Special Olympics, and other good works, while helping eager outsiders get a foot up on the ladder.

Everyone knows how the story ended, of course. First JFK and RFK were assassinated. Then, Teddy drove off a bridge in Martha’s Vineyard, killing a young staffer. His failed presidential run against Jimmy Carter in 1980 felt like an obligatory coda to the end of Camelot, before continuing on to a distinguished career in the Senate. Various third-generation Kennedys came and went from Congress and various statehouses. In the 1990s, John Kennedy, the former president’s olive-skinned, extraordinarily handsome, and personable son, briefly captured the country’s imagination, before dying with his very blond, very thin wife in a tragic plane crash.

Today, there are dozens of Kennedys with Ivy League degrees, quite a few of whom have had perfectly acceptable and even laudable careers at the middle rungs of the American governmental and corporate and nonprofit bureaucracies. As the family legacy faded, the torch was picked up by others. Bill Clinton presented himself as a wonky hillbilly successor to the Kennedys, inspired by his youthful encounter with JFK to pursue a life of public service, while selling out the American working class to the globalist gods. Barack Obama bought an enormous mansion on Martha’s Vineyard, but otherwise displayed little interest in the Kennedys and their mythos. Obama’s political chi came from his cool mastery of the politics of race and empire and his disdain for the American working poor, whom he redefined as white bitter-enders who clung to religion and guns. So much for the Kennedy family and the 20th-century Democratic Party.

With one exception. Anyone who hung around Kennedy political circles knew that in the collective opinion of the various longtime family friends, and speechwriters, and political consultants, and other hangers-on, who in one way or another saw themselves as custodians of the family brand, there was one member of the third generation of Kennedys who was said to have “it”—the family’s electric brand of political magic. Not Joe, the eldest of RFK’s children, who was dull and plodding; not Kathleen, a dedicated public servant who lacked personal charisma; not Caroline, who took after her mother; not John-John, who was a playboy; not Teddy Jr., who battled cancer and lost a leg; or Patrick, who was honest and sweet-natured but inherited his father’s problems with substance abuse and spoken language.

The heir to the family’s political mantle in the third generation of Kennedys was always Bobby. It was Bobby who became the leader of his tribe of orphaned brothers and sisters after their father’s death, trying and failing to make up for the absence of a charismatic father and the near-total absence of adult supervision. A friend who was close to the family in those years recalls visits to their home in Hickory Hill, Virginia, as like visiting a zoo—quite literally, with live sea mammals in the swimming pool, and animals of all shapes and sizes, frequently untamed, roaming freely throughout the house. Bobby’s hawks nested in the eaves and children climbed in and out of windows. Eventually, the friend’s mother forbade further visits, on account of it being too physically dangerous.

If the Kennedys were a kind of American royalty, then Bobby was their Prince Hal—charismatic and beloved, yet also dangerous and frequently out of control, a fatherless child who was trying to emulate the adult father figures who had been taken from him before he could truly understand who they were or what their brand of world-shaping masculinity meant. In 1983, Bobby was found nodding off in an airplane bathroom, and then pleaded guilty to heroin possession. The death of his brother David, who worshipped Bobby, a year later from a heroin overdose, made an uphill climb back to respectability seem even more unlikely, even after he got clean, and his decades of hard work as an environmental lawyer for Riverkeeper and the NRDC established him as one of the most effective environmental activists in the country.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Bobby kept his name alive in political circles through a familiar striptease dance with the New York press, which was no doubt orchestrated in part by his best friend from college, Peter Kaplan, the sharp-eyed editor of The New York Observer: A dutiful accounting of his environmental good works ridding New York’s waterways of deadly toxins, a dash of Kennedy fairy dust, a tour of his falcons—falconry being a lifelong hobby, pursued with characteristic dedication—and a tantalizing hint of a possible future race for some political office that would re-up his star power and help promote his advocacy. Of course, he never ran—which prevented the publication of the inevitable attack articles ripping him to pieces. Running would have been messy. His sister Kerry was married to the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo—heir to another political dynasty whose name meant more in New York state than the name Kennedy did.

Then it all came apart. In 2005, Kerry and Andrew Cuomo divorced. In 2010, Bobby separated from his wife, Mary Richardson, who had been Kerry’s college roommate at Brown and appeared to be suffering from substance abuse issues; a judge awarded temporary full custody of their four children to Bobby. In 2012, Mary Richardson hung herself. In 2013, Peter Kaplan died of cancer.

Meanwhile, Bobby Kennedy Jr. found success as an environmentally friendly venture capitalist along with a new cause: vaccines. In 2005, Kennedy wrote a blockbuster Rolling Stone magazine article titled “Deadly Immunity,” which presented compelling evidence of an ongoing vaccine safety cover-up led by U.S. national health bureaucrats, including transcripts of a 2000 CDC conference in Norcross, Georgia, where researchers presented information linking the mercury compound thimerosol with neurological problems in children. At its root, the case Kennedy made in his article was no more or less plausible and empirically grounded than the cases that he and dozens of other environmental advocates had been making for decades against large chemical companies for spewing toxins into America’s air, water, and soil, and then lying about it.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and his wife, actress Cheryl Hines, wave to supporters on stage after announcing his candidacy for president in Boston on April 19, 2023Scott Eisen/Getty Images

Yet the resulting journalistic-bureaucratic firestorm proved that vaccines were different. It also offered a preview of the COVID wars, with pressure campaigns by vaccine believers attacking five fact-checking errors in the article—a number that was hardly unusual for a long and complex reported article in a venue like Rolling Stone. The campaigns led to various emendations of the article by its online publisher, Salon, which eventually retracted the article in 2011. In that year, Kennedy founded the World Mercury Project, which would be renamed the Children’s Health Defense, to keep pressing his assertions about empirical links between vaccinations and the explosion of neurological issues in children. For anyone who knew Kennedy, his family, and his own record as an environmental advocate, the fact that he would sink his teeth in rather than let go was pretty much a foregone conclusion.

And so began the strangest and in many ways also the most promising chapter of Bobby Kennedy’s life. Stripped of the protection that the Kennedy name had once offered him, he was no longer the future secretary of something in some future Democratic presidential administration; he was a leper, banned from social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, repeatedly attacked by network television personalities and by members of his own family as an “embarrassment” and a “moron.” Meanwhile, his book attacking Anthony Fauci, the high priest of the COVID order, became an Amazon bestseller.

It is therefore easy to welcome the news that Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an heir to the political dynasty that sprinkled fairy dust on the 20th-century Democratic Party, is running for president. The collision he’s about to cause between the world of official group-think and the world of normal-speak—where most Americans weigh what might be best for themselves and their children—can only be good for American democracy, and for the American language.

It doesn’t take an alarmist to recognize how fast and far the term “conspiracy theory” has morphed from the way it was generally used even a decade ago. Once a description of a particular kind of recognizably insulated and cyclical counterlogic, “conspiracy theory” has become a flashing red light that is used to identify and suppress truths that powerful people find inconvenient. Whereas yesterday’s conspiracy theories involved feverish ruminations on secret cells of Freemasons, Catholics or Jews who communicated with their elders in Rome or Jerusalem through secret tunnel networks or codes, today’s conspiracy theories include whatever evidence-based realities threaten America’s flourishing networks of administrative state bureaucrats, credentialed propagandists, oligarchs, and spies.

Whenever a hole appears in the ozone layer of received opinion, it is sure to be quickly labeled a “conspiracy theory” by a large technology platform. The lab leak in Wuhan was a conspiracy theory, as was the idea that the U.S. government was funding gain-of-function research; the idea that the development of mRNA vaccines was part of a Pentagon biowarfare effort from which Bill Gates boasted of making billions of dollars; the idea that masking schoolchildren had zero effect on the transmission of COVID; the idea that the FBI and the White House were directly censoring Twitter, Google, and Facebook; the idea that the information on Hunter Biden’s laptop showing that he received multi-million-dollar payoffs from agents of foreign powers including China and Russia was real; and literally dozens of other officially declared falsehoods that turned out to be true. The most offensive thing about these falsehoods is not the fact that they later turned out to be supported by evidence, which can happen to even the most unlikely seeming hypothesis. Rather, it is that the people who labeled them “false” often knew full well from the beginning that they were true, and were seeking to avoid the consequences; that is how a truth becomes a “conspiracy theory.”

At this point, the fact that Robert F. Kennedy is the country’s leading “conspiracy theorist” alone qualifies him to be president. He is privileged, or cursed, to understand the landscape of American conspiracy theories, real and imagined, from the inside, in the way that even our greatest novelists have failed to do.

America’s last great generation of fiction writers were divided on the subject of conspiracy theories into three well-defined camps. The first camp, consisting of Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, Don DeLillo and their fellows, accepted an American reality defined by pop psychology, celebrity, and the power of individual narcissism—i.e., a somewhat more sophisticated version of the official American narratives presented on the nightly news and in Time magazine—with writers like Alice Walker and Toni Morrison doing their part by filling in the endlessly fascinating subject of race. It was no accident that both Mailer and DeLillo were driven to write endlessly long, fictionalized biographies of Lee Harvey Oswald that concluded that Oswald acted alone, while neither Morrison nor Walker displayed the slightest interest in who shot Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. For his part, Roth wrote two overtly political American novels, which concluded respectively that Richard Nixon was bad and that Charles Lindbergh was an antisemite. For all of these writers, the official version of American history was the necessary overarching framework for social, familial, and individual microhistories—though in his more overtly Jewish books, like The Counterlife, The Ghost Writer and Operation Shylock, Roth managed to escape the official version of Jewish history and became a much more interesting writer.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Larry David attend the 2016 Deer Valley Celebrity Skifest in Park City, Utah, on Dec. 3, 2016 Emma McIntyre/Getty Image

The second camp of American novelists were those who saw strange shapes moving beneath the murk. These included Thomas Pynchon, of course, but also William Gaddis; realists like Robert Stone and James Ellroy; and Ralph Ellison, the author of the single greatest 20th-century American novel, Invisible Man, a book which absorbed the literary energy of his great predecessor, William Faulkner, who as a Southerner necessarily dissented from the official version of everything. On one level or another, for all of these writers, the conspiracies were real, and the official version was a lie for squares. The third camp, the absurdists, who included Joseph Heller, Robert Coover, Donald Barthelme, Barry Hannah, and others, tried and in most cases failed to break the deadlock through deadpan comedy.

RFK Jr. has been, by degrees, a James Ellroy character, a Robert Stone character, a William Gaddis character, a Thomas Pynchon character, and perhaps now, a Ralph Ellison character, in that it may be fundamentally impossible for any American to see him straight. But it is very clear to which fictional camp his character belongs. He believes that conspiracy theories are not only real but define American reality. He grew up believing that the CIA most likely assassinated his uncle Jack, and lately, he has come to believe that it also assassinated his father. To walk through American life for the past 50 years believing that the government killed the Kennedys was to be fundamentally at odds with the gestalt; to believe in these conspiracy theories while also being a Kennedy must have been even stranger, to the point of making it impossible to be entirely authentic in public. Now that conspiracy theories have gone mainstream, who better than RFK Jr. to authentically understand and communicate with a public that is rightly suspicious of the poisons in its water and air, the dishonesty of the public health bureaucracy, and the toxic nature of official discourse.

At the age of 69, the latest Kennedy to run for president is a vigorous outdoorsman who looks at least 15 years younger than his calendar age. Reporters at his announcement last week were quick to notice the preponderance of swooning MILFs in the audience; projecting the kind of masculine charisma that is impossible to find on either side of the political aisle these days, Kennedy exudes the rude physical health of an older male supplement model. Relaxing in the backyard of his home in Santa Monica, the contrast with the geriatric president and his denatured courtiers, or the paunchy, cheeseburger-addicted ex-president, could not be greater.

The idea of a Kennedy leading a Jacquerie against the new authoritarianism of the best and the brightest may seem odd, or it may seem like a fitting last hurrah for the 20th-century Democratic Party, whose postwar incarnation become more or less synonymous with the Kennedys. It is too early to say whether his challenge to the unpopular Biden will turn out to be a mirage, or whether Kennedy—who after all these years has never held elective office at any level of government—is truly interested in becoming president. Still, this is a very much an era of black swans, and much stranger things, and worse things, have happened in America recently, by contrast with which the news of a Kennedy running for president seems quite normal.

I met up with Bobby Kennedy Jr. in the backyard of his house in Santa Monica recently for a talk that lasted for the better part of five hours. What follows are some edited excerpts from that conversation.

St. Francis and the Lepers

David Samuels (interviewer): I was an intern for your uncle Teddy in the 1980s, and in that period he had some pretty obvious drug and alcohol issues. And when he’d speak often there’d be this kind of Kennedyesque word salad that had no syntax to it that would come out of his mouth, particularly if he’d been drinking heavily. And you’d look at him and you’re like, what’s the mythos of this busted-up family all about?

So this was in 1985, at the height of the AIDS crisis, and one day they brought in a group of AIDS patients who were being left in locked hospital wards to die because even doctors and nurses didn’t want to touch them—that’s how bad the public ignorance and hysteria was about that disease at the time. And I remember that in the office, we were all freaked out that they were coming in and we were reviewing our playbook: What happens if one of them touches the furniture? What happens if one of them sips from a cup?

Then these people come in. Many of them looked like hell, weak, frail, with lesions on their faces. They looked like cancer patients. So we’re all kind of standing there, five or six of us, and we don’t want to get too close to them. And there was just this weird moment of silence, in which no one even thought to invite them to sit down.

And then Teddy comes out of his office. They start saying, “We’re being left in these hospital wards to die, and we’re here to talk to you,“ because he was the head of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, which was in charge of hospitals. He takes one look at them and you could see the response in his eyes. He walks over and puts his arms around the two patients who looked the worst, and suddenly he is hugging them. He starts reciting this mantra of “My brother Jack, and my brother Bobby,“ and talking about how everyone is equal, and deserves to be treated with decency and respect.

In that moment I realized that for him, it was entirely real. He understood that his mission in life, however flawed he was as a person, was to extend this mantle of protection. I remember walking out of there feeling stunned.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: I did a little book, a children’s book about St. Francis of Assisi, and one of the turning points of his life was leprosy. People didn’t know how it spread. They knew it was contagious in some way. So lepers were pariahs. They were excluded from society and they came to the wilderness and they were required by law to carry bells with them and to ring them as they walked to warn people away from their path. Immediately after his conversion, St. Francis passed a group of lepers on the street, on a road, and he got off his horse and he hugged and kissed one of them. He faced the thing that was his greatest fear because that love and compassion overcame that biological impulse of revulsion for risk of infection, which is hardwired into us from evolution.

Was St. Francis important to your dad?

Yes. At home in Virginia, there was literally a shrine on the second-floor landing. Then there was a shrine on the third-floor landing. Then there was one in the garden.

My father’s middle name is Francis. My middle name is Francis. He’s the most popular saint, so it’s not unusual. But, for me, he had a special meaning because of his involvement with animals.

Do you remember your dad with animals at all?

My dad would not let us have live feeders at home. I like snakes and I like poison snakes, and I like constrictors. I would bring them home, and he would not let me feed them mice because he thought it was cruel. He couldn’t stand it.

Did you explain to him, “Dad, that’s what they eat“?

Yes. And he was like, “No.“

He did let me have the hawks, though. But unless you go out hunting, you’re feeding just meat to the hawks. I wasn’t feeding them live animals.

I remember one time he found an evening grosbeak on the tennis court. He was sitting next to the tennis court. He had tweezers, and he was trying to straighten out its beak, which is not supposed to be straight. It looks crooked. I told him, that’s how it’s supposed to be.

He just had a natural compassion, and he couldn’t stand cruelty to animals or to human beings. He couldn’t bear it. It was unbearable to him.

Do you remember ever seeing him cry?

My dad? No.

Your father was a very gifted man, obviously, and a complex man, who didn’t fit neatly into any boxes. He was attached to the Catholic Church, in an age when normal members of the elite had disdain for religion. And he was not a big believer in big government. He was a champion of communities solving their own problems locally. Thinking back to your early memories of him—of what he wanted from you, what he taught you—what do you remember?

I think the most joyful thing is the amount of time that we spent outdoors, not only just every day playing sports and competition, but also taking us on wilderness explorations a lot. We went on all the big Western rivers, on the Snake, the Colorado, the Little Colorado, and the Green, the Salmon, upper Hudson, and many others, at a time when people weren’t doing that. Our lives were very, very rich, and we were very, very lucky.

But I’ll tell you another memory about my dad. It happened just before he left for the campaign, so a few months before he died. He called me into his office and he gave me a copy of Camus’ book The Plague. He asked me to read it, which he’d often do. He would give me poems or books or whatever, and asked me to read them. But this one he gave me with a particular intensity. I didn’t read it till after he died. When I did read it, I read it with an interest where I was trying to figure out why he gave it to me. What was the lock that this was the key for?

The book is about a doctor in a quarantine city in North Africa, and there’s a plague attack in the city, and nobody can go in or out. They never tell you what the plague is, but they know it’s contagious. They’ve never seen it before, and they have no idea how to treat it. A lot of the book is the doctor’s conversations with himself, because he knows that if he leaves and goes out and starts ministering to the sick, he’s almost certain to die. In any case, there’s very little he will be able to do, because there’s no treatment known. He’s convincing himself to stay locked up where it’s safe. Ultimately, he makes a decision to leave and go do whatever help that he can, because that is his duty. That is the duty of all humanity, but particularly doctors. That’s the subject of the book.

Camus was an existentialist, and one of my father’s favorite writers. The existentialists were the legatees of the Greek and Roman tradition of stoicism. The Stoics had that same philosophy, which is that you find meaning in your life. You bring order to a chaotic universe by doing your duty and not complaining about it. The iconic hero of Stoicism is Sisyphus, and Camus also wrote a book about Sisyphus.

Do you know where Camus wrote that book?

I assumed it was in France. In Algeria?

When he wrote that book, Camus was in hiding in a mountain village in France, because he was a member of the French resistance. In that same village, about a thousand Jews were being hidden. A friend of mine was a child who was hidden in that village, which was actually a group of three Huguenot Protestant villages, where they saved about 4,000 Jews by hiding them in their homes.

So Camus would wake up every day in hiding, but he was also aware of this whole other population that was in hiding in that village. It’s all abstracted in The Plague, but when he wrote it, he was living through something very concrete, which was Nazi fascism, and the very real fear of what would happen to him, and to the other hidden people in that village, if they went outside.

That’s a great story.

Anyway, the message of Sisyphus is that Sisyphus, of course, is cursed to push a boulder up a hill and to never get it all the way over the ledge. It always tumbles back on him at the top, and he’s supposed to do that for eternity, which you would consider something that would be a rather miserable existence. But in the minds of Camus and the Stoics, Sisyphus is a happy man because he undertakes his duty. He’s always pushing to get uphill, to make it, to improve the situation. He puts his shoulder to the stone, and he does what he’s supposed to do.

That, I think, really describes my father’s own decisions that he made in his life—particularly at the end of his life, his lethal decision to run for president. It gave me, I think, some important insight and direction that taught me how to live my own life.

Homing Pigeons

When did you first become interested in environmental law?

I was interested in the outdoors my entire life. I was obsessed with wildlife. I was in the woods every day of my life. At school, I was really ADHD. So I was always behind at school and I would sit in the back of the class and just think about getting back into the woods to check my traps and lines. I started seriously raising and breeding homing pigeons when I was 7.

How do you acquire your first pigeon?

It was a guy who lived next door to us, a farmer who was interested in animals, but he ran cock fights, rooster fights, and other stuff. And he was walking distance from my house, a couple across some cornfields, and he sort of took me under his wing. My mother ended up suing him, or he sued her. She stole some horses from him that he was mistreating and it was a big publicity case when my father was attorney general.

But before that, I had this relationship with the guy where he turned me onto reading and raising homers. We would put them on the train down to Delaware along with all the other pigeon fanciers and the homers would come back and when they came back into my coop, I would rush down to the post office and get them time-stamped. That’s how the system worked.

What made you connect your love of the outdoors to practicing law?

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a scientist or a vet. Then when my dad died, my priorities reoriented and I felt kind of an obligation to pick up the torch. So I went on a different path, which ended up in law school. And then when I was getting sober, after I went to law school, I kind of had to reorient myself around in ways that were sort of more true to myself. So that’s when I said, “OK, I’m going to do environmental stuff.“

Did you have a mentor in the process of understanding environmental law and how to use it?

I had a couple of mentors. One was John Adams, who was the head of NRDC [Natural Resources Defense Council]. And then Robert Boyle, he was a Sports Illustrated outdoor writer and editor for 60 years. And he founded the Hudson River Fishermen Association, and it was just a bunch of commercial fishermen and recreational fishermen—they were almost all former Marines.

In March of 196e6, the Penn Central Railroad was vomiting oil from a four-and-a-half-foot pipe in the Croton-Harmon railroad. And the oil went up the river and made the tides black and the beaches and made the shad taste of diesel. So the fishermen couldn’t sell them at the Fulton Fish Market in the city. And all the fishermen came together.

There’s a fishing village on the Hudson called Groutville. It’s 30 miles north of the city on the east bank of the river. And there the only public building was the American Legion Hall. Groutville had the highest enlistment rate per capita of any community in America and most of them are Marines. And they got together in this American Legion Hall in March of 1966 to talk about blowing up the Penn Central pipes, and also about floating a raft of dynamite into the Indian Point Power Plant, which at that time was killing a million fish a day on its intake screens. Somebody suggested they put a match to the oil slick coming out of the Penn Central Pipe and burn up the pipe. And somebody else said they should roll a mattress up and jam it up the pipe and flood the railyard with its own waste.

And then Boyle stood up. He had written an article about these fishing clubs made up of these weirdos and oddballs, these very colorful characters, for Sports Illustrated. But in researching the article, he had come across an ancient navigational statute called the 1888 Rivers and Harbors Act that said it was illegal to pollute any waterway in the United States, and you had to pay a big penalty if you got caught. Also, there was a bounty provision that said that anybody who turned in the polluter got to keep half the fine.

And he had gone to the libel lawyers at Time Inc., which owned Sports Illustrated, and he said, “Is this still good?“ And they looked and they said: “In 80 years it’s never been enforced, but it’s still on the books. So technically it’s good.“

So when all these men and women, 300 people were crowded in the American Legion Hall talking about violence because their livelihoods and property values were being destroyed, he stood up with a copy of that law and said, “We shouldn’t be talking about breaking the law, we should be talking about enforcing it.“ And they resolved that evening, they were going to start a group that was then called the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association. They were going to go out, track down, and prosecute every polluter on the Hudson.

Eighteen months later, they collected the first penalty in United States history and the first bounty in United States history against a corporate polluter. They got to keep $2,500 from Anaconda Wiring and Cable, who were dumping toxins in Hastings, New York. Then they sued American Filter in 1973. They got $200,000 and they used that money to construct a boat. And they then began patrolling the river and they hired me using bounty money in 1984. They were still called the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association and it was not that well organized. I mean, they had a charter that required them to have a mixer, a dance for fishermen once a year.

Then we started methodically suing every polluter on the Hudson. We brought a couple hundred lawsuits, and we collected I think over $3 billion in remediation and penalties. Hudson today is the richest waterway in the North Atlantic, produces more pounds of fish per acre, more biomass per gallon than any other waterway in the Atlantic Ocean, north of the equator. It’s the last major river system left that still has strong spawning stocks of all of its historical species of migratory fish.

Regulatory Capture, Pollution, and Vaccines

What did you learn about corporate America from your decades leading that group—which eventually became Riverkeeper, right?

The way that Riverkeeper began was when Art and Ritchie Garrett, both former Marines, went to the Corps of Engineers and they went to the State Conservation Department to beg them to stop Penn Central Railroad from vomiting oil into the Hudson. And the colonel who ran the Corps of Engineers, whom they visited 11 times in Manhattan, he finally told them, these are important people—meaning the Penn Central Board of Directors, we can’t stop them. [The Garretts] realize, “Oh, OK, government is in cahoots with the polluters.” If you’re a big shot, you can destroy people’s livelihoods. You can privatize the commons, you can poison the fish, and nobody’s going to stop you because you own the regulatory agencies.

What does owning regulatory agencies mean?

There have been hundreds of articles, and I’ve written books on regulatory captures. There are a lot of mechanisms by which powerful economic entities in a society are able to capture the regulators that are supposed to be protecting the public. It happens in every country. I mean, you see less of it in Canada than you do in New York, for example, or Louisiana. But it’s happening everywhere.

There are huge economic incentives to pollute. So the polluters are able to figure out ways to turn those agencies into sock puppets for the industry that they are supposed to regulate.

And when you go to Monsanto or Exxon or any of these companies that you sue and say, “Hey, you guys, you’re dumping this shit into the water and it contains mercury or whatever that could be harmful to kids, so why don’t you stop it?”, what kinds of responses would you get?

The official response from those entities is sophisticated. And you’re usually dealing with lawyers, who are very guarded.

The interesting question that I think most Americans have is: Why would a corporation like Monsanto or General Electric poison all the fish in the Hudson if it’s their fish too? And that question was answered by Sinclair Lewis, who said that it’s impossible to persuade a man of a fact when the existence of that fact diminishes his salary. There’s an economic law called “tragedy of the commons,” which basically says an individual following their own economic interests will capture and kill the last fish in the ocean no matter what it does to the rest of society.

So those people are able to put blinders on to persuade themselves that they’re creating jobs, that they’re doing good things, and they judge themselves by their intentions rather than their actions. And ultimately their ultimate redoubt is, I can live in Aspen, or I can live in Hawaii, or I can live in a gated community, and the mayhem that I’m creating for other communities will not reach my door.

So the idea that large pharmaceutical companies might be using additives or using processes that could cause damage to children didn’t come as a shock to you.

What was a shock to me was the economic entanglements between the pharmaceutical industry and the regulatory agencies—which were, to me, unprecedented in my previous experience. The EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] is a captive agency, but it’s captured by the coal industry, the oil industry, and by the chemical industry. When we tried the Monsanto case, we got papers where the head of EPA’s pesticide regulatory division had a secret communication with Monsanto where he was telling them, “I’m going to kill this study and you need to give me a medal when I’ve done it.“ He was not working for the public. He was working privately and secretly for Monsanto. And that’s pretty common. That’s basically typical regulatory capture.

But with pharma, you have the entire agency that is dependent on pharmaceutical revenue.

We need this study, and we need it done in a year, and here’s your million bucks.

Right. We need this drug approved in a year, so we’re going to pay you extra to fast-track it. And that money, the regulatory agencies become dependent on it.

At NIH [National Institutes of Health], as it turns out, they’re doing very little in the way of basic scientific research. What NIH should be doing is saying, OK, what’s the answer to this interesting question: Why is it that in my generation, I’m 69, the rate of autism is 1 in 10,000, while in my kids’ generation it’s 1 in 34?

Now, I would argue that a lot of that is from the vaccine schedule, which changed in 1989. But what nobody can argue about is that it has to be an environmental exposure of some kind.

I saw a number the other day, it said that 45% of American children now suffer from a chronic disease.

It’s more than that. The 2006 study is 65%. I think 45% suffer from obesity, at least in some states. It’s 40, 47%, I saw, in Oklahoma, Mississippi, and West Virginia.

And you know it has to be an environmental exposure because genes do not cause epidemics. 1989 was the year that a lot of these changes happened. The food allergy stuff suddenly became epidemic. Rheumatoid arthritis became epidemic. Juvenile diabetes, a whole host of allergic-type disease like anaphylaxis, eczema, food allergies, peanut allergies, etc., asthma, went to 1 in every 4 African American kids in cities. You had this explosion of neurodevelopmental disorders, ADHD, speech-related, language-related, tics, Tourette syndrome.

In fact, Congress said to the EPA, tell us what year the autism epidemic began. The EPA is a captured agency, as I said, but it’s not captured by pharma. They came back and said, “1989, it’s a red line.“ What happened in 1989 was some kind of ubiquitous exposure that affected every demographic from Cubans in Florida to Inuit in upper Alaska, affecting boys at four times the rate of girls. What happened?

Phil Landrigan, who’s probably the premier toxicologist alive, and who has been the expert in a number of cases for me, and who does not agree with me on vaccines—he did a peer review article that said these are the 11 things that fit that timeline. And it was like glyphosate, neonicotinoid pesticides, ultrasound (which was interesting), cellphones, plastics, bottled water plastics, and a few others.

Now, if you’re the head of NIH and you’re trying to protect American health, you say, “OK, this is helpful. It’s got to be one of these 11 things. Let’s design some studies to figure out which one it is, and we’ll make some policy recommendations.”

Did that ever happen? No. The opposite happened, which is: The NIH will ruin your career and bankrupt your university if you try to do that study.

If you were saying, “My name is Bobby Kennedy, and I’m representing an organization called Riverkeeper, and we are taking on Monsanto, which is a big company that is dumping chemicals associated with birth defects into your water,“ people look at you and say, “Good for you, Bobby.“ So why do you think emotionally, psychologically, that once you took on this other set of big companies, pharmaceutical companies, which work with a different set of chemicals, and started accusing them of some similar practices, suddenly that made you into a dangerous weirdo?

Well, it’s actually even a narrower question than that, because if you ask any Democrat or liberal, are the pharmaceutical companies greedy, evil, and homicidal, and are they committing mass murder with a lot of products like Vioxx, which killed 120,000 people, every Democrat and every liberal will tell you, “Yeah, those companies are pure distilled evil.“

The opioid crisis kills 56,000 young Americans every year, and they knew it.

Right. Everybody knows big pharma is crooked. So if you’re a Democrat and a liberal, you have to say yes, they are crooked in every aspect of their business—except for vaccines.

I think the three big pharma companies have paid $35 billion in criminal penalties and civil damages over the last decade or so. So they’re chronic felons. Why do you think that just with this one product they found Jesus and they are going to behave?

So, Are You an Anti-Vaxxer?

An “anti-vaxxer“ is a very bad thing to be, in any kind of polite society. Of course, the alternative is to accept that it’s absolutely normal for there to suddenly be 27 mandatory vaccines in the state of New York, half of which no one ever contemplated 10 years ago. Also, you must believe that every one of those vaccines is immaculate and perfect, because the companies making them would never, ever lie to us—and if you don’t believe that then you are also against vaccinations for polio. Which is absurd.

It strikes me as a religious type of belief. Ultimately, they require you to suspend critical thinking and to believe a trusted authority. I think that’s a biological impulse that people have that comes to us from the 20,000 generations we spent wandering the African savannah. Little groups, where there’s a boss, and you had to obey them or you would perish. The people who are imposing these orthodoxies are pressing all of those buttons.

Pro-vaccine means you are part of the group. If you are not, then you are no longer part of the group.

And then you find the person who’s not in that group who you can say is evil and a threat to everything we believe in. So you point to Donald Trump and you say, either you believe him or you believe us.

Although of course Trump is the one that brought us the COVID vaccines, right?

He brought us Fauci. He brought us the vaccines. He allowed Fauci to kill ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, and he brought us the lockdowns and all that. But they ignore that. And they say, OK, Fauci is good, Trump is bad. And anybody who tries to depart from that orthodoxy is dangerous. And you have to discredit them. You cannot debate them. The heretics must be burned. They must not be allowed to speak.

Do masks work to stop COVID?

The Cochrane collaboration, Cochrane Library, which is the premier authority for scientific clinical reviews, came out this week and said that masks, both the masks, the N95 and the regular surgical masks, are useless. And we looked at the studies, the existing literature, at the very beginning, and we collected it all in one place and saw the same thing. What Tony Fauci said originally was true: Masks don’t work against respiratory viruses during a pandemic.

The weird thing, which surprised me, is that my assumption was that the cloth masks, of course they don’t work, because the holes in them are 200 times the size of the virus. But then I started actually reading the literature and there’s this huge 1982 study, it’s either University College or Royal College of London, they said, we’ve been using masks in the surgical theater and elsewhere for 80 years, but there’s no study of how effective they are. Let’s do one. For six months, nobody’s going to wear a mask. As it turns out, the infection rate went down, even in the surgical theater.

I mean, my assumption is, I want my doctor wearing a mask in the surgical theater, because I do not want him sneezing into my open chest cavity. But as it turns out, the science doesn’t even support that! It was an exercise not in public health, but in control.

Right.

They became these instruments of moral signaling or sanctimony, that I’m wearing a mask, meaning I’m compliant. I’m showing my willingness to obey. It struck me from the beginning, that convincing populations to put on masks, there was something creepy about that.

Because, if you look at the ambition or the intention of every totalitarian system, it’s ultimately to end the capacity for group action, for communication, to control all communications and every aspect of human behavior, from monetary exchanges to political organizing to sex. This is the ambition, the intention, of totalitarianism. And what is more repressive than forcing somebody to cover their mouth and their face. “No,” it says, “you cannot communicate.” God or evolution has equipped the human face with 42 different muscles for expressing all kinds of subtle skepticism.

My entire life as a reporter, I never interviewed anybody over the phone for exactly this reason.

You want to look in their face.

Ninety percent of the information that you’re going to get about somebody’s going to come from their face, from the way they move their body. That’s how humans communicate.

I also think that the very skilled use of fear has the capacity to disable critical thinking and make people run for the safety of authority. If you read the last chapter of my Fauci book, I go through all these tabletop simulations, which I uncovered, and there’s plenty of them that were organized by the CIA beginning in 1999, almost every year since, involving that model, which is the use of a pandemic to clamp down totalitarian controls and to obliterate the Bill of Rights. And they do it again and again and again, and it’s astonishing.

None of them talk about, how do you boost immune systems? How do you stockpile vitamin D? How do you link frontline physicians to figure out what therapies and repurposed medications are working and efficacious against the disease? It’s all about, how do you immediately impose censorship? How do you get people locked down in their homes, when all of the manuals on pandemic management say you do not do mass lockdowns. How do you do social isolation and impose all these social controls?

It was training frontline physicians in every country in Europe and Canada and the United States, Mexico, and Australia, that when the pandemic comes, the response to it is to impose totalitarian control and some censorship.

It’s like a Rorschach test, right? This is who these people are, deep down. And this is what some part of them, at least, is looking to do.

This is exactly what they did in COVID, in all of these liberal Western democracies. Trudeau was a huge protector of civil rights and human rights. All of a sudden they all pivot in lockstep and do the same thing: Masks, lockdowns, mandatory vaccines.

I agreed that it was a really weird thing to watch, especially after the first two, three months. You’re like, why is this happening this way? Why does it keep going?

And the marginalization, the vilification, and delicensing of physicians and scientists, and people, regular people, said, hey, I just got injured by the vaccine. My daughter died. My son died. I’m paralyzed.

He was an athlete in high school, and now he just suffered a heart attack.

On the field. And those people are punished and they’re vilified rather than treating them with compassion.

The Military-Pharmaceutical Complex

I want to keep going for a little while about the pharmaceutical complex itself and the responses to COVID. It’s clear that there was a large-scale Pentagon bio-weapons program. Bill Gates was brought in as a partner for the investment in that program. Research for that program was offshored to labs in China. It seems obvious now that the virus likely escaped from one of those Chinese labs. And that there was funding for exactly this kind of research from the U.S. government at that specific Chinese lab that the virus escaped from. So why isn’t there an effort to create some kind of chain of legal responsibility for the enormous amount of damage that was done, the same way you would do if Monsanto was dumping toxins in the water?

First of all, it wasn’t just the military that ran the funding for the Wuhan lab. It was the military and the intelligence agencies. The EcoHealth Alliance was a CIA front. USAID, which was the biggest funder of the Wuhan lab, has a long, long connection to the CIA, and they had a much bigger investment in it than NIH did. So you have all of these U.S. military and intelligence agencies who are running the lab, and then killing the investigation. So there was a State Department investigation immediately, and Vanity Fair documented how people with intelligence agency credentials from the nonproliferation branch of the State Department ordered the investigation to stop specifically because it would implicate the U.S. military and intelligence agencies.

But I’m asking you, as someone who participated in 300 environmental lawsuits, why isn’t this a lawsuit?

Because if you look at how it was done, they gave themselves complete immunity from liability. You can’t sue them. If you look at actually who produced this vaccine, it was not Pfizer and it was not Moderna. It was military contractors, and it was the Pentagon. They did it under a series of provisions that were created after 2002, between 2002 and 2019, that allowed the Pentagon to evade any regulatory authority.

I’m not talking about the vaccine, though. I’m talking about the damage done by the virus itself, which is a man-made creation.

Oh, I misunderstood your question. I think there will be litigation on that, eventually. I feel we have enough evidence now that if I were allowed in front of a jury, that I could convince virtually any jury in our country that we made the virus, that this was a U.S. government and Chinese government collaboration.

Church Was Something That Was Miserable for Me

Would your father wake you up to go to church? Was that a thing you did with him?

My father? We went to church almost every day.

Really?

Yeah, particularly in the summer. We went every day in the summer. Sometimes twice.

And he’d go with you, once or twice a day?

Yeah.

What do you recall that being like? Because that’s pretty intense.

Church was something that was miserable for me.

Because you had to sit still indoors? You wanted to be outside?

Yeah. I would just count it down, in minutes.

What was your dad’s attitude?

I think my mother was the one who was the secret police when it came to church.

You’re going.

You’re going. And my grandmother, too.

My father, when we were in church, they had this odd mixture of piety and irreverence and skepticism towards clerics. Their faith was a paradox. It was not simple, because they came from the Irish tradition, which has a lot of piety, but also a lot of rebellion. It creates cognitive dissonance in your brain if you try to reconcile it, because it makes no sense.

That’s why you have to laugh, right?

Yeah. My father would read the church papers when he was in church. He would look at what the church was saying.

I think they really loved Pope John XXIII. The Catholic Church is a public organism. Its atomistic origins, at their best, are Christ’s Gospels and what I think we now call Gnostic Christianity, when it was people meeting in basements and sharing Christ’s gospels and the message of love and tolerance and compassion. I think the way that they saw Pope John is that he was trying to restore that aspect of the church.

What kind of lessons or stories do you remember your father telling you or asking you as kids, to give you a sense of history?

My father came home from the Justice Department and had dinner with us almost every night. He was a very good war historian, and he would talk about the battles that changed history, particularly the battles of the American Civil War and the American Revolution. We grew up knowing all the battles of the Civil War and the Revolution, including obscure characters, because my father was really interested in all of those things, the War of 1812, etc., but also the Greek wars. We also heard a lot about what they were doing in the White House, the Civil Rights movement, and—

Did he talk to you about World War II?

Yeah, lots. All the time.

Because he lost a brother in the war. Right? He lost a sister.

Yes. But also, it was the big event of their entire milieu. He lost his brother-in-law. Kick’s husband got killed on the Maginot Line. Billy Hartington, my uncle Billy. My uncle Joe was killed. A lot of their friends were killed.

We also talked a lot about the Germans and about what had happened during the Holocaust. I remember him talking about Anne Frank and asking us, if you were in that situation, would you hide Anne Frank if she came to your door? And we said, yeah, of course we would hide her.

It was kind of like a moral character test. What side do you think you’d be on in that situation? And that made an impression with me, and it stayed with me the rest of my life.

As little Jewish kids, you grow up asking a different question, which is you look at your neighbors and you say—

Will they hide you or kill you?

Exactly. And only as you get older do you start to realize it’s pretty fucked up, because other little kids are not really asking that question about their neighbors.

Your dad went to Palestine in ’47?

Yeah, in ’47. For the Boston Herald.

His dispatches are very interesting because he obviously identified with those Palestinian Jews, as they were then known, the Israelis, very strongly. I don’t know if it was in part because they were fighting the British, but whatever it was, the fact that they were fighting for their own independence seemed to make an impression on him. Did he talk about that?

I remember in the ’67 war, I was at the pool next to him, when I think Johnson called him and told him the war had just begun. It was either Johnson or somebody from the White House. It may have been McNamara.

And I was the first person my father turned to because I was sitting next to him on the chaise lounge. And he got up and I remember he put on his glasses and he was going to go up to the house. And I said, “What’s happened?“ And he said that a bunch of the Arab countries had attacked Israel, including Egypt. And it was Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Kuwait.

I knew how tiny Israel was because at that time, everybody took geography.

The great, lost fucking discipline.

In Catholic school, we had to fill in every African country. We were given a map of Africa, Asia, and we had to fill in all the countries that we knew.

And I just thought how this little, tiny sliver of a country was going to fight against these huge countries with tens of millions of people in them.

And I was like, “Is Israel going to get destroyed?“

And he said to me, he said, “No, the Israelis are tough.“

For my father to use that, that was his supreme accolade. The word “tough“ was the highest thing that he could say about anybody. So I knew who he was rooting for.

You’d hear about the Freedom Riders or Martin Luther King?

Yes, all of that. We had the Freedom Riders at our house. There were always Cubans in our house, from the Bay of Pigs. We went horseback riding every morning before breakfast, at 6:00 a.m., when we were in Virginia. We would ride through the CIA, and we would ride around a development there where my father had found homes for a lot of the brigade members. He would go by and we would talk to them. My mom and him would help them get health insurance, help them get kids in school, and find them homes.

These were the Bay of Pigs and then the Operation Mongoose people?

Operation Mongoose, yeah. My father did not like the CIA guys who were running Mongoose. He had a very antagonistic relationship with them. He liked Harry Ruiz, who was the engineer who had been a part of the Bay of Pigs, who was one of his closest friends. He had followed Castro, so he had been against Batista.

There were many different components of the Bay of Pigs group. Some of them were old Batista murderers and torturers and soldiers. My father believed that we should be supporting a revolution in Cuba, but he did not believe that we should be assassinating Castro.

Who Killed JFK?

You never heard your father speculate or imagine any kind of connection between Cuba, the Bay of Pigs, and Jack’s death?

Well, no.

My father’s first reaction to the day, I do remember.

I got picked up at my school, at Sidwell Friends, and then brought home when Jack was shot. He had not died yet or been pronounced dead. We were brought home. So I was at home with my father when [J. Edgar] Hoover called my father and told him that my uncle was dead.

When I got home, my father was walking in our yard, which was a six-acre farm. He was walking with [CIA Director] John McCone, who I knew because the CIA was less than a mile from my house, and McCone would come over every day. After the office closed every day, he would come and swim in our pool and do laps before he went home. He would say hi to my mom and dad. Sometimes, they’d have cocktails.

My father was walking with him, and my father asked McCone, “Did our people do this?“

My father made three calls. One, he called the CIA, and he asked a desk officer, “Did you guys do this?“ He got McCone on the phone. McCone came over, and he asked McCone directly, “Did the CIA do this?“ Then he asked Enrique Ruiz Williams.

Harry Ruiz Williams was very, very close to my family. He came on ski trips with us. He was eating dinner at our house all the time. He was the liaison between my dad and a lot of the other community who had a very complex relationship with my family. Early on, we were heroes. Later on, a lot—

You left them to die.

Right.

But he called him at his hotel. He was there with a journalist, I forget that guy’s name, who wrote the official chronicle of the Bay of Pigs, which is called The Bay of Pigs, and he was a friend of my dad’s, and I grew up knowing him. He and Harry Ruiz Williams were both staying at a hotel in Washington, D.C., at that time. He called them and he said, “Did your guys do this?“

So my father’s first instinct was the CIA had done it.

But what happened with my dad is, first of all, he was shattered and just did not pursue it. He was in darkness and, at that point, he didn’t care who killed my uncle. He was just—

Gone.

He was gone, and there was nothing bringing him back. My dad was just trying to survive.

At that point, immediately after Jack’s death, my father also lost 100% of the investigative capacity of the Justice Department, because Hoover no longer was reporting to the attorney general. He was reporting to Johnson. So my father didn’t have an investigative arm anymore. So even if he wanted to quietly look into my uncle’s death, he didn’t feel he had a way to do it.

Then as he came out of that darkness and depression, he began turning to the war and to politics, and he went into the Senate in ’64.

A couple of years later, like I guess ’66 or ’67, he was walking through the National Airport with Frank Mankiewicz and Walter Sheridan. And he said there was a magazine stand there that had a lot of magazines with James Garrison on the cover. And he pointed to Garrison, who was then investigating my uncle’s death and thinking that the CIA was involved.

And he said to them, “What do you think about him? Does he have anything?“

And they said, “We think he does.“

So they went down, or Sheridan went down there. And what he came back with is that he got a look at Jack Ruby’s telephone records right before the assassination. And he was struck that virtually everybody that my dad had subpoenaed and convicted who was in the Mafia had been in touch with Ruby a month before.

And at that time, you have to remember that nobody knew at that time, the link between the Mafia and the CIA, that there was really just one organization, when it came to certain types of operations.

So my father, I think, at that point, was thinking, “Well, maybe it wasn’t the CIA. Maybe it was the mob. And maybe they did it because I was prosecuting him,“ which was really, I think, hurtful to him.

But then a week before he was killed, about a week before he was killed, he was campaigning here in California and he spoke at a community college in Los Angeles.

And up to that time, when anybody asked him about the Warren Commission, he would kind of mumble.

He wasn’t going to say it was right and he wasn’t going to go against it.

Right. Because if he started questioning it, he would marginalize himself and he would lose his capacity to talk about the war and about what was happening in the cities, which are the two things he wanted to be effective on. And he would’ve looked nutty.

So whenever anybody asked him about it, he would mumble something that was noncommittal. And he said privately to his aides that it was a shoddy piece of work. And my father knew more about investigations than anybody. He had already investigated the mob. A devastating investigation. He had been attorney general. He knew how the CIA operated. He knew how the FBI operated.

And you did pick up from him, when you were a kid, a hostility towards the CIA?

Yes, absolutely.

So he was at a community college here in Los Angeles. And a student said to him, and this is a week before the primary, he knew he was going to win California. And if he won California, he was going to win the convention, in his head. Because the two guys who stood between him and the White House, he had already beat both of them. He beat Humphrey in ’60, and he had beat Nixon at ’60. He knew how to beat them, and he was not scared of it.

And one thing, the night of a primary, something happened he knew was going to happen, which was Richard Daley called him and said, “I’m going to grease the skids for you in Chicago.“

So at that point, I think my father knew that he was going to be president. He believed, anyway, that he would be president.

So a week before, he already sees California’s going his way.

And a student said to him, “If you become president, will you reopen the Warren Commission?“

And if you listen to the tape, there’s a long silence. And then he says, “Yes.“ And that’s it.

I think that would’ve scared a lot of people because he knew how to do an investigation and he would not have been steamrollered.

He showed that card.

Who Killed RFK?

Do you remember your father telling you that he was going to run for president?

I remember that whole time, yeah. I remember him staying up all night, writing the speech.

And then I went to the announcement with him, in the Senate caucus room.

And there was a lot of excitement. There were people in the house, all of his aides, and Adam Walinsky and Dick Goodwin, were all there typing the speech all night. Arthur Schlesinger. So yeah, we knew that he was going to run.

Were you guys scared? As his kids?

No.

You didn’t think someone could kill him the way they killed your uncle?

You know what? I don’t think that’s the way any of us thought. We all thought, they’re involved in a war. And it’s like war, where you take your risks.

There was no one among the kids who said—

There’s a lot worse things than dying, by the way.

Well, that’s a thing that either your parents teach you, or they don’t.

Yeah. So I think that was the way that everybody looked at it.

The person who ostensibly shot your father here in Los Angeles, Sirhan Sirhan, was ostensibly motivated by the fact that your father was pro-Israel, wanted to sell U.S. fighter planes to Israel. He shot your father on what for him was the first anniversary of the Six-Day War, the ’67 war. Or do you understand that event differently?

Well, at this point, I think Sirhan was part of that ambush of my father. I do not believe that Sirhan actually killed my father.

But for many years, my understanding of it was the conventional understanding, which was that Sirhan had killed my father because my father had committed to defending Israel in the presidential debates.

My understanding of what happened, of the assassination, is more complex now. I do not believe Sirhan actually fired the bullets that killed my father.

Were you persuaded by the evidence of the tape, where you can hear many more shots than Sirhan Sirhan fired from his gun?

No, the thing that persuaded me, that first persuaded me was Paul Schrade, who was standing beside my father—he was the vice president of the UAW and a very close friend who had discovered Cesar Chavez and introduced him to my father. But he was also shot that night. Five or six years ago, he basically forced me to come over to his house and sit at his kitchen table and read Thomas Noguchi’s autopsy report. And once you read that, it’s impossible to believe that Sirhan had killed my father.

Because Sirhan fired two shots at my father. He had a revolver with eight shots in the chamber. And he fired two shots. One of them hit the door jamb behind my father and was later removed by the police. The other one hit Paul Schrade. And then his gun was turned. He was pounced on by ultimately six people. A big dog pile, who pinned him on a steam table, and forced the gun away from my father.

Rafer Johnson [who helped subdue Sirhan] talks about how this little man, he had superhuman strength. And they could not wrest the gun from his hand. And he fired off six more shots. All of those shots hit people. We know who they hit. One person got hit twice, through his clothing once, but the shots were going away from my father.

According to Noguchi’s autopsy, my father was killed by four shots fired from behind him.

Sirhan never got behind him. Sirhan was in front of him. And those shots were all contact shots. So they left carbon tattoos on his body, which means the barrel of the gun could never not have been more than an inch from his body, and in some cases were clearly touching his body. And they were fired upward, at upward angle, suggesting the person who fired them was holding the gun close to his body and concealing it while firing it upward.

The fatal shot was the one from behind his ear.

Sirhan never got that near. There were 77 eyewitnesses, and everybody placed Sirhan five feet in front of my father.

So who do you think did fire the shots that killed your father?

I think the person who did it was [Thane] Eugene Cesar, who was the security guard who had just got the job two nights before. And who was holding my father’s elbow. He hated my father, and he—

Why?

He was very racist. And he thought my father was handing the country over to Blacks.

And he was also a CIA asset. He had top security clearance at the Lockheed plant. And he had just gotten the job as security. And he’s the one who steered my father into the ambush. He grabbed my father’s elbow.

My father was not supposed to go into the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel.

Don’t they usually say that was Fred Dutton who brought your dad into the kitchen?

But Cesar picked him up at the doorway and guided them into Sirhan’s ambush.

And then he pulled his gun.

There were 12 people who saw him pull his gun. My father clearly knew he was being shot from behind because he rotated and pulled off Cesar’s tie, his clip-on tie. And as he fell, he had the tie in his hand.

He fell on Cesar and Cesar then pushed my father off of him and stood up with his gun drawn.

When he was asked later, “Why did you have your gun drawn?“ He said, “I was firing at Sirhan,“ but that didn’t happen.

And then he lied about what he did with the gun.

His gun was ultimately recovered. There’s people here in Los Angeles who are testing it right now, but it made a long, bizarre sojourn, where it was stolen by teenagers, it was thrown into a lake, and it was sold to another guy. A month after my father’s death, Cesar sold it to another guy from the Lockheed plant who was retiring and went to Arkansas.

And he told the police he had sold that gun and he told the guy, “This was used in a crime. Don’t ever show it to anybody.“

He told the police he had sold that gun in May before my father’s death, but the guy from Arkansas said, “No, he sold it to me in July of ’68.“

Then a bunch of things happened with that gun, that ended up now with a collector here in Los Angeles.

And then the ballistics do not match. And there were more shots fired than Sirhan had. There are too many conundrums to explain that it was Sirhan Sirhan. It doesn’t make any sense, when you start looking, at even a cursory examination of what happened that night.

The LAPD brought in a special team to do the investigation. It was called the Special Units Center. And that team were all LAPD officers who had been trained at the farm in Virginia at CIA’s headquarters, and then dispatched to duty in Los Angeles, in Latin America for the CIA. And then were brought back to this investigation. Prior to Sirhan’s trial, there were 2,800 photographs destroyed by the police and incinerators. And a lot of the material evidence was also destroyed. It was a very bizarre case.

Any lawyer could have gotten Sirhan off anyway, because the ballistics didn’t match. But unfortunately, Sirhan was given a lawyer who was also the lawyer for [famous American gangsters] Mickey Cohen and Johnny Roselli, who had their own involvement in the JFK assassination. And they provided him with the lawyer who told him to plead guilty.

What do you remember about the months after your father being killed?

Well, I mean, it was just a wasteland. It was a twilight zone in our house. The older kids were all sent away for the summer. My brother David was sent away. Because my mother had all these kids at a home, and she was trying to figure out how to manage this family.

The horrible story about David was that he had actually seen the murder live on TV, right?

Yeah. He was in Los Angeles and watched it on TV. And then nobody remembered him for several hours. So he was sitting in a room, alone, watching reruns of my dad being shot. And he kind of never recovered from that.

My brother David went that summer to Delano, to work for Cesar Chavez.

My sister went up to Alaska to work for the Inuit.

My brother Joe was sent to Seattle to work as a guide on Mount Rainier for Jim Whitaker.

I got sent to Africa, with Lem Billings. I spent a lot of the summer with Tom Mboya, who was a Kenyan labor leader who loved my father. He was in line to be the successor to Jomo Kenyatta. And he was then assassinated.

I remember one of your cousins once told me about going to your house, I guess it would’ve been in the early ’70s. And they remembered it as being quite literally a zoo. I remember them saying, “Bobby had animals everywhere. And then kids were climbing out onto the roof from the windows. And my mom was like, ‘No more visits because it’s fucking out of control.’” Was that the way it was?

I think my mom liked that chaos and she endorsed risk-taking, and there were a lot of emergency room visits. And then she liked the animals, too. I mean, we had a seal living in our pool for a long time. We had a lot of other animals. We had a full farm yard of cows and coats and geese and ducks and pigeons. We had nine horses. I had a basement filled with possums and raccoons and coatimundis. Then I had all my hawks.

So what did you need heroin for?

Listen, I was 16 years old. I would say I was out of control. At that point, drugs did not have the same kind of stigma that they have today. We’re talking about—

I had 15 years where I was high every day, so I am not judging you or your 27-year-old self.

I was what I’d call an addict for 14 years. I was using drugs for 14 years before I got sober.

I became an addict the same reason most people do, which is they have a big empty hole inside, and that was the one thing that would fill it.

How did you get clean?

I went to 12 steps.

You just went to meetings or did you go to the—

No, I went to a rehab, but I didn’t go to a 12-step rehab. I went to something called Fair Oaks.

I lived with heroin addicts. I don’t know how anybody quits heroin. It becomes part of you. Being able to quit that as a young man and stay off it is—

Those other people who do it probably start off a little bit more reckless than your average alcoholic.

You built an integrated life.

How the Kennedys Gave Us Barack Obama

Tell me more about Tom Mboya

Tom Mboya was a Luo. I had first met him in 1960, when he came to our house on the Cape, to try to airlift kids to America, to attend college. It’s an interesting story because he was then the only Kenyan who had attended college. He’d been to Oxford for two years. He was a labor leader and he had been part of the Mau Mau with Kenyatta. But he came from a little tiny tribe called the Luo. And they’re a fish-eating tribe up in Lake Victoria. And they’re known as super smart, but also peacemakers.

In 1960, he came to my house because he had realized the British had said, OK, we’re going to give you independence. You got five years to get your act together. He had looked around and he said, “There’s not a single kid in this country who has a college education. How are we going to govern ourselves?“

So he wrote letters to 200 American colleges and he said, “Will you give a free ride, a full scholarship to a Kenyan kid? I’m going to choose the 200 smartest kids in Kenya.“

He got 200 colleges to agree, including Harvard. And he got all these kids. And then in the middle of the summer, he realized he didn’t have any money to get them over.

So he flew over, went to the State Department, said, “Will you give us money to bring these kids over?“ And Nixon was VP, running for president, and thought if he airlifted Blacks from Africa, they would kill him in the South. And Blacks in the South were a key vote because they could go either way. At that point, they had been traditional Republicans, but Roosevelt had gotten a lot of them to switch over. But you didn’t want to screw around with the whites in the South, who were also up for grabs.

And so then Tom Mboya went to see Martin Luther King. And Martin Luther King said, “Maybe you should go to John Kennedy because he’s on the African subcommittee and he’s a big African nationalist.“

And he introduced Mboya to Harry Belafonte. And Harry Belafonte, who was friends with my parents and Jack, he brought him to our house and we all got to meet him.

Now I had been obsessed with Africa since I was 7. My father had brought home a film called Africa Speaks, and put it on our screen in our basement, a 16-millimeter screen. And I had read every book about Africa. I had read all the Tarzan books. I read The Blue Nile, The White Nile, everything. So to meet a real African was a huge thrill.

Then I went over in ’64 with Sargent Shriver, and we spent a lot of time with Tom Mboya and his son, Bobby. We went and I spent the summer over there.

And then when my father died, I spent the summer there and we spent most of the summer with Tom Mboya. And in August of ’69, Tom Mboya was assassinated, by Daniel arap Moi.

Who then became president for Life.

Right. So then in 2004, I gave one of the keynote speeches at the Democratic Convention in Boston. I was living with Larry David, at that time, in Martha’s Vineyard. And they asked me to give this speech on the environment, which is now a big Democratic issue.

Right. Along with Barack Obama.

Yeah. So Larry and I flew up. And Larry gave me a ride up in his plane. And then we spent the day on the floor of the convention.

And in the green room, before I spoke, we met Barack. And I spoke, and then he spoke. And we saw him speak, and he just blew the roof off the thing. Nobody ever heard of him. He’d only been one year in the Senate. But then we talked to him afterwards and we were having a lot of fun. And we said, “Where are you headed?“