The Supreme Court Punts on Censorship

by Matt Taibbi | Jun 26, 2024

The Supreme Court today punted on Internet censorship, sending free speech advocates back to the drawing board while Joe Biden’s White House celebrated.

“The Supreme Court’s decision,” said White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, “helps ensure the Biden administration can continue our important work with technology companies to protect the safety and security of the American people.”

That “important work,” of course, includes White House officials sending emails to companies like Facebook, with notes saying things like “Wanted to flag the below tweet and am wondering if we can get moving on having it removed ASAP.” The Supreme Court sidestepped ruling on the constitutionality of this kind of behavior in the Murthy v. Missouri case with one blunt sentence: “Neither the individual nor the state plaintiffs have established Article III standing to seek an injunction against any defendant.”

The great War on Terror cop-out, standing — which killed cases like Clapper v. Amnesty International and ACLU v. NSA — reared its head again. In the last two decades we’ve gotten used to the problem of legal challenges to new government programs being shot down precisely because their secret nature makes collecting evidence or showing standing or injury difficult, and Murthy proved no different.

I’m not going to lie. It’s a bummer. For plaintiffs like Drs. Jay Bhattacharya and Aaron Kheriaty, for their lawyers and the Attorneys General of Louisiana and Missouri who brought the case, and for those of us who worked on the related Twitter Files stories, this is certainly a disappointment. Given that the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security reportedly resumed contact with Internet platforms after oral arguments in this case in March led them to expect a favorable ruling, it’s logical to assume the Big Brothering will now resume in earnest.

The court zeroed in on the issue of “traceability,” i.e. the ability of plaintiffs to demonstrate that suppression of their content was “traceable to the Government defendants” like the FBI, the Surgeon General, the White House, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). After summarizing the issues with each defendant, the court wrote:

We begin—and end—with standing. At this stage, neither the individual nor the state plaintiffs have established standing to seek an injunction against any defendant. We therefore lack jurisdiction to reach the merits of the dispute.

I wish I could report that the court did not, in fact, discuss the “merits of the dispute.” In more than one section the court did have things to say about the evidence in the case. I’ll get into this in more depth later, especially after I’ve had a chance to talk to parties in the case, but the decision contained passages that stung, for example:

And while the record reflects that the Government defendants played a role in at least some of the platforms’ moderation choices, the evidence indicates that the platforms had independent incentives to moderate content and often exercised their own judgment. The Fifth Circuit, by attributing every platform decision at least in part to the defendants, glossed over complexities in the evidence.

This suggests the court was impressed by the popular argument that because the platforms only followed through with government flags or requests at a roughly 50% clip, and “often” exercised their own judgment, communications from the state were not inherently coercive. To me this suggests all the state has to do to circumvent First Amendment restrictions is make flagging requests in quantity, and leave platforms room to kick a few. I wonder if the court would have been more inclined to focus on the “merits” if they saw, say, one out of two FBI claims honored, instead of the much bigger numbers presented. Moving on:

On this record, it appears that the frequent, intense communications that took place in 2021 between the Government defendants and the platforms had considerably subsided by 2022, when Hines filed suit.

The idea that “frequent, intense communications” had “considerably subsided” by the time the suit was filed is a head-scratcher. The court spent a lot of time on the issue of the plaintiffs’ failure to show “likely future harm,” noting “the past is relevant only insofar as it is a launching pad for a showing of imminent future injury.” From a non-legal perspective it may seem obvious that continued pressure from state enforcement agencies will result in injury to someone, or many someones, but the Justices wanted more specificity with regard to individual defendants. Lastly, a smattering of comments from the reviews of various defendants like the CDC, FBI, and CISA:

The platforms often asked the agency for fact checks on specific claims. (CDC)

These agencies communicated with the platforms about election-related misinformation. (FBI/CISA)

Until mid-2022, CISA, through its “switchboarding” operations, forwarded third-party reports of election-related misinformation to the platforms. (CISA)

The Director of Digital Strategy and members of the COVID–19 response team interacted with the platforms about their efforts to suppress vaccine misinformation. They expressed concern that Facebook in particular was “one of the top drivers of vaccine hesitancy,” due to the spread of allegedly false or misleading claims on the platform. (White House)

The court appeared to completely accept the idea that communications from the state were in reaction to “misinformation” and that agencies like CDC were correct arbiters of fact. They missed or ignored the glaring central issue of the case, which was that the state was often wrong, and voices like those of Harvard’s Martin Kulldorff, Stanford’s Bhattacharya, and Kheriaty of the University of California were likely suppressed for correct disagreement with state directives on issues like Covid-19 mortality rate or the efficacy of lockdowns or natural immunity.

As a matter of law I don’t think it matters if the government violates the First Amendment to suppress false information versus the truth, but from the standpoint of the court of public opinion, I believe it matters quite a bit. Censorship advocates have been very successful in keeping the public conversation away from the fact that the state (and especially the health authorities during the pandemic) has so often been factually incorrect in its efforts to suppress content.

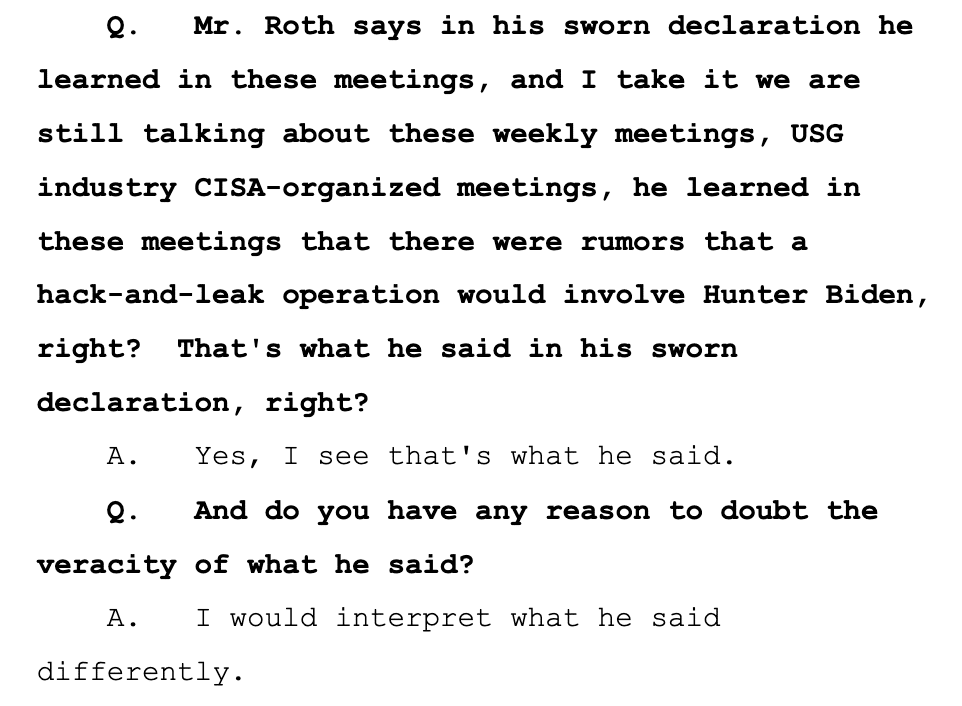

The related matter that Senators Mike Lee and Eric Schmitt tweeted about just last night, i.e. the FBI’s false briefing to the Senate telling them the Hunter Biden story was Russian disinformation, is another key element to this story. Schmitt, who brought the original case on behalf of the state of Missouri, noted that he’d deposed FBI agent Elvis Chan, and added: “The FBI was peddling the same lie to Big Tech to pre-bunk the story in advance of the 2020 election.”

This ties into the First Amendment issue because if agencies that are assumed to be authorities like the FBI are in fact spreading misinformation or disinformation, it’s particularly important to protect the rights of citizens or media who might choose to publicly contest that disinformation. The issues with suppression of medical professionals around Covid-19 touches on the same problem. In other words, irrespective of the standing issue the Supreme Court cites, which may or may not be valid, the pretense that all the suppressed content in the case was misinformation — which is definitely incorrect — was ratified in the way Justices described the case.

Murthy v. Missouri may not have been a perfect challenge to digital censorship, but I’m struck by the difference in the way the appellate judges in the Fifth Circuit responded to the evidence, as opposed to the Supreme Court. The appellate judges reacted like people. They read profanity-laden tirades directed at the platforms from the White House, and blithe recommendations regarding exactly how much this or that media figure should be deamplified and expressed instinctive revulsion and outrage, before collecting themselves and delivering a careful and limited ruling. The Supremes clearly did not find this conduct surprising or upsetting in the slightest, which is the problem.

The Supreme Court, irrespective of its partisan construction, has been shrugging at outrages to the Bill of Rights since 9/11. The national security establishment increasingly becoming a black box during that time has made these challenges harder. But kudos to the plaintiffs and their lawyers for attacking anyway, because terms like “traceability” and “nonjusticiable” and “special factors” are all the spy state has in its defense.

They’re wrong, they know it, and thanks to this case, the public knows it too, no matter what reprieve the high court gave them today.

0 Comments