Unnatural Economics

by W.D. James | Feb 26, 2025

We like to dislike financiers (and usually lawyers).

In a sense, this is odd. Personally, my interactions with bankers have mainly been positive; then again, I’ve never had anything I own foreclosed upon or repossessed. That’s largely because I’m very conservative financially: the only things I have ever financed were vehicles (to meet actual transportation needs), a home to live in, and my education – never luxury goods, vacations, capital to gamble or ‘speculate’ with, etc…, and I’ve been fortunate to avoid serious disability or some other circumstance that would negatively impact my ability to earn revenue, like a major depression. All have been pretty sound investments and I am grateful I could borrow money to acquire these items. Anyway, the issue is not with specific people working in the banking sector but with overarching economic structures. My interactions with lawyers have been less salutary, but that is another story (though, again, my interactions with attorneys as friends is positive, but lawyers acting in their official capacity – not pleasant).

On the other hand, I know many people have more negative interactions: Woody Guthrie told the truth when he said some men will rob you with a six-gun and some with a fountain pen. So, there is some real distinction between a productive loan one might take out in a sort of win-win manner and a more predatory situation where really only the banker wins.

To delve into the intricacies of this in our modern economy gets really complex really quickly and I’m no economist or financier and am barely credible as an ethicist. I will not even broach the intricacies of international finance, the sort of financial commodities that led to the 2008 economic crisis, financial schemes that are really landgrabs, or the global system that maintains some nations in perpetual debtor status.

So why this animus against financiers? Some of it may be experiential (personal or historical experience of the rich and powerful of the world and their manipulations and domination). Some of it may be cultural such as literary depictions of financiers like Shakespeare’s Shylock and his pound of flesh. I think a good part of it though is a deep intuition that something is fishy with finance, per se.

Critical Economic Theory

Some might think that Proudhon or Marx were the first critical economists. However, critical economic theory goes back to the beginnings of the Western intellectual tradition and actually predates a non-critical economic theory: people have always had a gripe with the economic arrangements of their day!

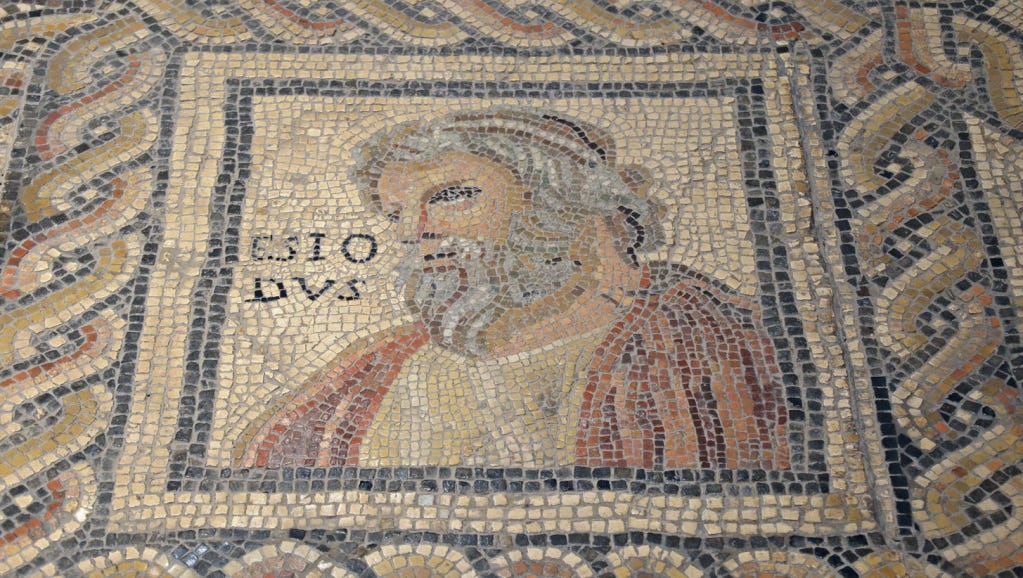

Hesiod, who, along with his rough contemporary Homer, gave us the first comprehensive written account of the Greek gods (in his Theogony), also gave us the first economic critique in his Works and Days, which includes some practical farming advice about planting and harvesting vis a vis the phases of the moon and what not. It’s really about how his brother legally cheated him out of his share of their inheritance though (perhaps the earliest record of the dislike of legal maneuvering, though there weren’t really lawyers yet).

Though not really a theorist properly speaking, he has a deeply rooted sense of natural justice and when applied to economics his sense is that a fair day’s labor entitles one to a day’s sustenance. If one labors and gets less one is either the victim of fate (drought, locusts, natural disaster, angry gods, etc…) or one has essentially been cheated – someone else got part of what you worked for. If you labor and get more you have been really blessed or you were on the cheating end of the equation. This seems to be a deeply rooted moral intuition: if one works one should be able to eat (and if one does not work one should probably go without – even affirmed by St. Paul in the New Testament, though of course there are many mitigating factors).

That is, Hesiod thinks nature has a hand in our economic activity and the moral norms which should govern it – it isn’t just convention (legal, cultural, or historical).

Natural Law Economics

So, if you know my thinking at all, by the time I’ve mentioned ‘nature’ and anything Greek, I’m probably about to turn to Aristotle (or maybe the Stoics) and so it is in this case.

In Book One of his Politics, Aristotle gives us an account of ‘acquisition’ and what forms of it are according to nature and which are contrary to nature (all of the below quotes and references can be found in chapters 8 through 10 of Book One). We need to keep in mind that when Aristotle speaks of something happening naturally or according to nature, he typically means two things. First, it is how we will observe nature, as a complex, self-sustaining whole, in fact operating: for instance, each living sort of thing comes into existence, reproduces itself, then passes away. It will also mean the characteristic way in which each thing realizes its own species’ nature: how dogs are doggy and palm trees palm treey. Further, these two are always in harmony: nature as a whole is sustained by each type of being being the sort of being it is and playing its role in the overall symphony.

Aristotle starts by observing that nature provides a means of subsistence for each species consistent with its nature. Some species are naturally herding animals, some not. Some are predators, some prey, some combine both roles. Each has a unique “way of life.” He observes: “It is the business of nature to furnish subsistence for each being brought into the world…”. Each has a way of gaining its subsistence consistent with its way of life: hunting in packs, grubbing off the bottom of bodies of water, etc… For humans, each community adapts to its environment, with some naturally being hunters, some fishers, and some farmers. This may just seem like a truism: yes, nature provides for each species to gain its sustenance, if it didn’t that species would starve and go out of existence. But Aristotle has discerned a sort of natural standard for economic (getting our living) activity: sufficiency. In the human sphere, if some in the community start to fall below that level or others start to rise much above it, an Aristotelian will start to look carefully at what is going on.

Humans are different from most other species in that we can innovate and plan more intentionally (say stocking up a reserve for future lean years). Also, we are the only species that can choose to act unnaturally. We can do this in the moral sphere by choosing to violate the natural law of our species and we can choose to do this economically by choosing to follow natural modes of acquisition or choosing to follow modes contrary to our nature.

The natural mode Aristotle subsumes under the topic of “household management” as households, families, are held to be natural by Aristotle (the natural forms of association being the family, the village, and the polis).i Essentially, natural acquisition will aim at sustaining this natural association aimed at the natural human telos, or aim of our lives, of “flourishing” (morally, socially, individually). Only acquisition aimed at supporting these naturally given aspects of our existence constitute true wealth on his account because they contribute to our ultimate good. To provide a down-to-earth contemporary application of this, Aristotle would affirm it is natural, and therefore good (conforming to our human nature), for the people in a household to acquire sufficient resources to allow them to meet all their needs (clothing, shelter, education, healthcare, culture, etc…) in a way consistent with the overall good operation of the household. So, unnatural means would be ones that compromise that. Perhaps members of the household spend more time physically outside the home than is consistent with their other non-economic duties to the family. Perhaps they put so much effort into acquiring a surplus (over and above sufficiency) that they are not able to carry out the other tasks associated with the flourishing of their nature. Perhaps the children are worked so hard that their education or health are sacrificed. Aristotle is insisting that commodities or money gained in a way that is not consistent with our overall flourishing should not be considered ‘wealth’ as they undermine, rather than contribute to, our flourishing.

This is also giving more content to the notion of a ‘sufficiency.’ For creatures of our sort, bare material existence is actually not sufficient: we must make provision for the social, cultural, moral, and religious aspects of our natures as well. As one example, consider the ‘high-achieving’ professional of our day who puts in 80 or more hours per week at the office or who travels continuously. Presumably they do this to gain the large pay check (and I assume the esteem that goes with that sort of work). Aristotle would refuse to call them wealthy because their mode of acquisition is overbalanced in gaining money and under balanced toward active engagement with the family in the household. Also, leisure has its place in human existence.

There are a couple of mistakes such a person is making. First, they have failed to give the natural aims of human existence overarching significance. I think our entire modern civilization probably makes this mistake. Secondly, they have failed to notice that nature sets a natural limit to acquisition: what is sufficient to meet all genuine human needs. Finally, this disguises the great economic error/evil on Aristotle’s account: the idea that there is no limit to good acquisition. Is $100,000 better than $50,000? Is $5,000,000 better than $1,000,000? Is $100B better than $75B? Our mathematical ability pushes us to affirm the superiority of the larger amount in each pairing. Aristotle wants to show us though that more does not always equate to better (one being a measure of quantity, the other of quality).

Let’s say you would need $75,000 to meet all the natural needs of your family and have a pack of flourishing humans. In that case acquiring $60,000 is probably better than acquiring only $50,000 as you will be able to meet more needs and flourish to a greater extent. This is assuming the funds are acquired honestly and in ways not socially detrimental to the broader community (because as social beings we also depend on the larger community to fully flourish and so the good of the human community must be factored in as well). However, when we make decisions that will lead to acquiring $100,000 we have to start asking ourselves what are we sacrificing to obtain that surplus and how does it bear on our family’s overall flourishing? Aristotle is not a Puritan or a strict follower of mere moral rules and certainly no ascetic. Maybe the decision is consistent with overall flourishing and maybe it isn’t: it depends on the circumstances. But the mistake we make is to assume there is no limit to acquisition and more is always better – that error we must always, individually and socially, guard against. This is the great error, even sin, of unnatural modes of acquisition, what our medieval forebears would have termed contra naturam. At an even higher level of analysis, Jesus asked what does it profit you if you gain the whole world but lose your soul? It’s the same impeccable logic, just applied to a different framework of value.

Natural Exchange

Aristotle distinguished between the use value of a thing and its price in retail exchange. As something of a side note, this bears a striking similarity to Marx’s distinction between use and exchange value of a commodity (its utility in satisfying a human need and its value on the market which often diverge significantly). Also, Marx’s conception of ‘Species Being’ represents a slight echo of Aristotle’s understanding of species natures. Finally, Marx openly developed and enriched Aristotle’s conception of potentiality (our ability to fulfill our nature and thereby flourish) by layering on historical constraints: how the economic system of a particular time impacts our ability to develop our potentiality.

Based on this distinction, Aristotle was able to distinguish between natural and unnatural exchange. Natural exchange occurs when people exchange products which each serve to meet actual, natural, human needs: I give you some of the bread I have made in exchange for some of the cheese you have made. Further, natural exchange is characterized by justice. In this case, justice means the exchanges are of equal value. Aristotle held that the natural value of a product is the amount of labor it takes to produce it, so a fair and just exchange would be me giving you the amount of bread it took me X hours to bake in exchange for the amount of cheese you made in X hours. An unequal exchange would be operating under the imperative of profit, not use.

Why would that be a bad thing? Profit is our God, or at least the lifeblood of a capitalist economy. The reason is that our economic activity is supposed to operate under the overarching aim of living well, living a good flourishing life. Use values contribute in a direct fashion to that. Profit introduces a foreign factor. For one, it entails unequal exchanges so it cannot be consonant with the overall flourishing of the whole community. More importantly it substitutes a non-moral (or probably immoral) aim for economic activity. When we make and trade based on profit (gaining money) instead of satisfying our natural needs we have adopted the wrong standard and this will tend to undermine our flourishing. Unlike natural physical laws (such as gravity), you can break natural moral laws all day long. However, you can never escape the consequences of breaking natural laws of either sort; they occur inexorably: jumping off a cliff will leave you splatted at the bottom and acting contrary to natural morality will damage your being.

So, Aristotle sees something unnatural in all economic activity conducted for profit. The empire of profit ignores and is contrary to the regime of human flourishing. What of that commonsense intuition that there was something wrong with financiers we opened with? Aristotle notes: “Hence we can understand why, of all modes of acquisition, usury is the most unnatural.” How so?

- Usury is unjust. It is not an equal exchange: it demands on the loan of X amount of currency a repayment of X+Y amount;ii

- This denatures currency which Aristotle understands as a means of exchange, not a means of obtaining profit;iii

- Currency is dead matter and to expect it to increase is an unnatural expectation; a boy and girl cow left to their own devices may well produce more cows, two bars of gold left alone to their own devices will not produce a third;

- Usury denies natural limits to accumulation; and

- Hence, it represents the adoption of the false standard of profit in the most unnatural way.

All of this is very alien to our modern ways of thinking about economics. Obviously, modern capitalism did not exist during Aristotle’s time. This is not to suggest that if Aristotle showed up today he might change his mind or be just fine with our new, improved modern ways. For modern economics to develop, Europe had to go through a process of banishing Aristotelian thought and natural ethics. If Aristotle showed up today I think he would be like: ‘no wonder you’re so screwed up; you are very unnatural.’ ‘You are governed by oligarchs (who by definition have the wrong standard of values). The more your GDP increases the more depressed and socially dysfunctional you become. Your economy is structured on the false assumption that money has value in and of itself, disconnected from the satisfaction of natural human needs. It is so bad you’ve even forgotten your actual nature. How can you hope to be happy (flourishing)?’

Subscribe to Philosopher’s Holler

Footnotes:

i For a much more thorough look at Aristotle’s conception of human nature, natural association, and the natural aims of human living see my previous “Revolutionary Aristotelianism” series. I have used the classic Ernest Barker translation.

ii In a modern finance economy this becomes more complicated. This complication is reflected in the evolving teaching of the Catholic Church (which remains essentially Aristotelian). In the medieval period, all lending at interest between Christians was morally prohibited. The exemption created of lending between Jews and Christians is momentous. Usury has almost disappeared from Canon Law, but remains in the Catechism of the Catholic Church as a grave sin, though mainly in the context of international finance which produces hardship and even death for those in the borrowing country. It’s complicated, but the basic thing that changed economically was that once upon a time the monetary resources one would have had basically just had to sit around in one’s back room or inside one’s mattress. When it becomes possible to invest money for a return, then there is an actual cost to the lender (the forgone money made by the investment) which it is just to expect the borrower to cover. Also, I think the Church has gotten a bit soft on this matter, especially in its own dealings.

iii The thought of John Locke is central to understanding the modern rejection of Aristotelian economic ethics. Locke shared his ‘labor theory of value’ but redefined the role of currency from a medium of exchange to a non-spoiling store of value. I hope to examine this in detail at some point. By doing so, Locke seeks to justify unlimited accumulation. For now, I’ll just note that Locke’s fundamental mistake is to banish natural human ends (our telos, a conception of flourishing tied to our nature) from his political and economic thought. All of modern liberalism follows him.

0 Comments