Wars, resets and the global criminocracy

by Paul Cudenec | Jun 10, 2024

Over the last few years, I have been doing a bit of research into the connections and parallels between the Great Reset and war.

Although my focus has been mostly on the First World War, I have come to the conclusion – shocking for some, perhaps, but utterly unsurprising for others – that the agenda behind all modern wars is the same as that behind the Great Reset, Fourth Industrial Revolution, New World Order or whatever else you choose to call it.

This agenda – a long-term and multi-faceted agenda – is that of the entity I have taken to calling the criminocracy, a global mafia which, as I explained in my booklet Enemies of the People, is dominated by the Rothschild financial and industrial empire.

The overall aim is the consolidation and expansion of the criminocracy’s power and wealth, the two terms being virtually synonymous in this corrupted era that René Guénon termed the Reign of Quantity.

We can break this down into three aspects:

Short-term goals – ie: given that the whole thing is ultimately about money, immediate financial advantage.

Medium-term goals – ie: the setting-up of forthcoming financial advantage.

Long-term goals – the creation of the social conditions which will be to the financial advantage of the criminocracy in decades to come.

As far as short-term financial advantages to the Great Reset are concerned, as reflected in its initial Covid phase, they are quite obvious.

Firstly there were the profits from the sale of the so-called vaccines themselves – purchased and indemnified across the world by public authorities in an atmosphere in which there was no room for democratic scrutiny or debate.

Secondly, there was all the new equipment that could be sold, again globally, on the back of the so-called pandemic: face masks, plastic screens, handwash, signage, PCR tests and so on.

Thirdly there was the financial advantage gained by large businesses, particularly those operating online, from the lockdowns that severely affected smaller businesses.

In fact, Klaus Schwab of the WEF openly boasted about this in his 2020 book Covid-19: The Great Reset.

He wrote: “In the US, Amazon and Walmart hired a combined 250,000 workers to keep up with the increase in demand and built massive infrastructure to deliver online. This accelerating growth of e-commerce means that the giants of the online retail industry are likely to emerge from the crisis even stronger than they were in the pre-pandemic era… It is not by accident that firms like Alibaba, Amazon, Netflix or Zoom emerged as ‘winners’ from the lockdowns”. [1]

In terms of war the most obvious cause of quick profit is from sales of armaments.

The arms trade is a key part of the criminocratic empire – as revealed by the term “military-industrial complex”.

At the time of the First World War, for example, Britain’s arms trade was controlled by a monopolising ring based around Vickers Ltd; Armstrong, Whitworth and Co Ltd; John Brown and Co Ltd; Cammell, Laird & Co, and the Nobel Dynamite Trust.

Historians Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor, who show how the criminocrats created and prolonged the war for their own profit, note: “The ring equated to a vast financial network in which apparently independent firms were strengthened by absorption and linked together by an intricate system of joint shareholding and common directorships.

“It was an industry that challenged the Treasury, influenced the Admiralty, maintained high prices and manipulated public opinion”. [2]

War also calls for vast amounts of raw materials, not just to manufacture the guns, ammunition, tanks, ships and aircraft, and all the associated paraphernalia, but also to transport goods and men over oceans and continents.

The Rothschild gang’s dominant role in the global oil industry, as well as in iron and steel and in railways, meant their cash tills were ringing heartily from this huge surge in demand – on both sides of the 1914-18 conflict.

There are other aspects of immediate financial gain, in the past and in the present, that are hard to identify with precision, because they fall into the realm of clearly criminal behaviour and thus are even more carefully concealed than other forms of skullduggery.

Two centuries ago, during the Napoleonic wars, the Rothschilds took advantage of food shortages and spiralling prices to operate on the black market in their home city of Frankfurt and sold provisions to armies at a considerable profit.

British goods, including cotton fabric, sugar, indigo and tobacco, were also transported across the Channel, via the Rothschilds’ warehouses, in defiance of Napoleon’s blockade.

War-related sanctions can be a profitable affair for those with the right contacts.

“Humanitarian” relief in wartime is often a convenient cover for massive and highly dubious transfers of money.

Docherty and Macgregor explain how, in the First World War, “aid” to Belgium amounted to “one of the world’s greatest con jobs”. [3]

The Commission for Relief in Belgium hailed itself as “the greatest humanitarian undertaking that the world had ever seen”. [4]

It later claimed to have spent over $13,000,000,000 on relief for the people of Belgium, a truly staggering figure for the period.

The man in charge was Herbert Clark Hoover (pictured), later president of the USA, whom the two authors do not hesitate to describe as “a confidence trickster and a crook”.[5]

With a certain inevitability, it turns out that he was deeply connected to the circles that had planned the very disaster which he was now allegedly alleviating.

Explain Docherty and Macgregor: “The American-born mining engineer lived in London for years and was a business colleague of the Rothschilds… He held shares in the Rothschilds’ Rio Tinto Company and was associated with the same all-powerful Rothschild dynasty which invested in his Zinc Corporation”. [6]

“When Herbert Hoover negotiated the massive loans for Belgian Relief from Allied governments he used the J.P. Morgan organizations in America, co-ordinated through Morgan Guaranty Trust of New York which, in turn, made the requisite transfer to London”. [7]

“Financial muscle was never far from his center of power. The Morgan/Rothschild axis was wrapped around the entire project”. [8]

According to a report from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy earlier this year, 2024, global aid to Ukraine had already reached $278 billion, and billions more dollars are being lined up. [9]

It is interesting to note that, back in 2007, The New York Times predicted that a member of the young Rothschild generation, Nathaniel, (pictured) “may become the richest Rothschild of them all” thanks to “bold bets in this era’s new-money investment vehicles” and the family’s traditional geopolitical foresight. [10]

It added: “The man in line to be the fifth Baron Rothschild is close to becoming a billionaire through a web of private equity investments in Ukraine”.

The medium-term source of financial profit from such grandiose rackets arises from the huge amounts of public money that are thrown into them under the pretext of an “emergency”.

The “magic money tree” of public spending suddenly becomes infinitely bountiful when faced with the all-eclipsing “crisis” of pandemic, war, terrorism or climate change.

For instance, the British government estimates the total cost of its Covid-19 measures as ranging from £310 billion to £410 billion. [11]

Some of the most expensive schemes included the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (sometimes called the furlough scheme) and NHS Test and Trace.

As to the key question of where exactly this money came from, with tax revenue down because of lockdowns, it reports that it increased borrowing to £313 billion in 2020/21 alone.

Borrowing from the global bankers, that is.

Lucrative loans to governments for waging wars have been part of the Rothschilds’ racketeering playbook since Napoleonic times.

Historian Niall Ferguson notes that the banking family found themselves “repeatedly on both sides of decisive conflicts which were to recast the map of Europe”. [12]

The aftermath of war was also a great source of profit. In 1871, the Rothschilds were on hand to lend massive amounts of money to the French state to pay off its reparations after defeat to Prussia, in what Ferguson describes as “the biggest financial operation of the century”. [13]

The post-war dividend also comes from loans and contracts for the “building back better” of devastated countries.

The third way in which the criminocrats profit from wars, as from the Great Reset, is the long-term effect such events have on society.

The cash-starved states involved, up to the neck in debt, have no choice but to go along with the bankers’ idea of how best to rebuild their countries.

After both world wars, the idea of a “post-war” reality, to which people had to adapt, was used to ramp up industrialism and modernity, destroying traditional agriculture and communities and declaring old ways of thinking and living as being unsuited to the brave new normal.

Schwab hoped that Covid would have the same effect, creating a new historical separation between “the pre-pandemic era” and “the post-pandemic world”. [14]

All such showcase events, including most so-called “revolutions” and so-called terrorist attacks like 9/11, are, in my view, merely “shock and awe” operations designed to push traumatised populations further into the prison-camp society favoured by the criminocrats.

Rootless, helpless, disorientated, brainwashed people, entirely dependent on the system for their every need, cut off from each other, from nature, from reality and from spiritual belonging, are the ideal fodder for the criminocrats’ money-making machine.

With this in mind, is not surprising that in each case we see the same means being rolled out to ensure that populations go along with the agenda.

Most obvious is the full-on propaganda from all the state and corporate media.

In 2020 it was the tone and extent of this propaganda, as encountered via French state radio, that indicated to me that the Covid “pandemic” was a psy-ops.

This propaganda has to go so far as to create a sense of absolute moral conviction in the population and thus a conditioned fear or hatred of anyone who refuses to toe the line.

In times of war, dissenters and doubters are portrayed as cowards, traitors, fifth-columnists working on behalf of the despised enemy and during the Covid scam we were represented as irresponsible and selfish idiots, putting the lives of others at risk and perhaps following some insidious “far-right” agenda.

To help impose this moral conformity, the system deploys groups which it apparently does not control and whose positions carry moral weight with certain key parts of the population.

During Covid, the “left” not only echoed every part of the official narratives concerning lockdowns, social distancing and so-called vaccines, but also adopted a very aggressive stance towards dissidents, vilifying and ostracising anyone, even from their own ranks, who dared sympathise with pro-freedom protesters – as I myself experienced, in fact.

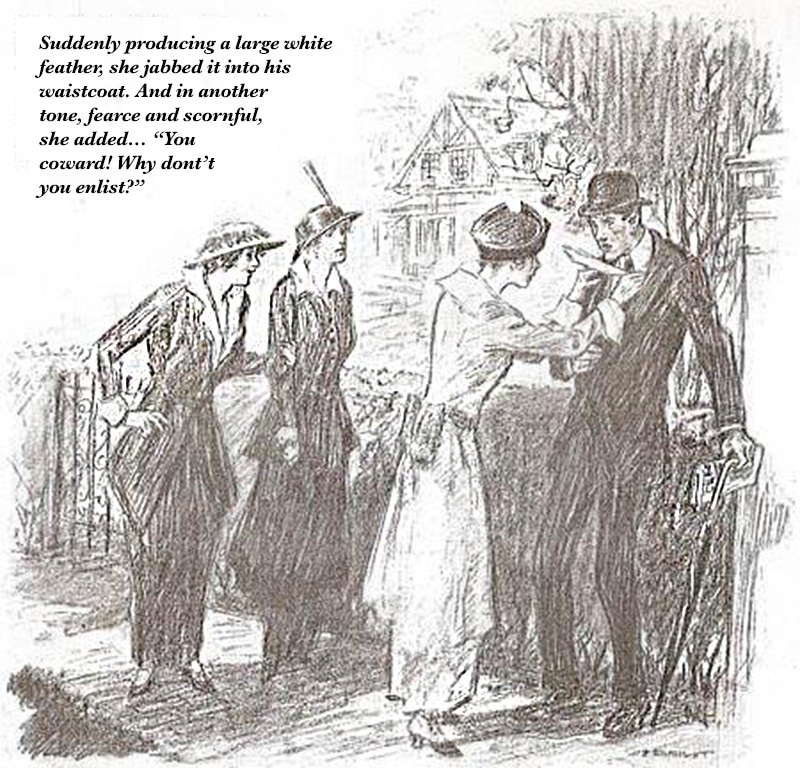

During the First World War, one of the groups wheeled out to support the criminocratic agenda was a wing of the Suffragette movement.

Apparently in return for agreeing to stop their militant activities, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst were handed a government grant.

Emmeline declared her support for the war effort and began to demand military conscription for British men, while Christabel Pankhurst demanded the “internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores”. [15]

And the suffragettes were among those women who handed white feathers to males not in uniform, including teenage boys as young as 16.

Along with propaganda, comes censorship, considered quite normal and acceptable in times of war and justified during so-called pandemics in the name of the public good.

But today the mission of the “fact-checkers” introduced during Covid is evolving into a broader attempt to defend the criminocratic agenda.

With so-called “hate” laws being hurriedly rolled out all over the place, the main target seems to be those of us who have seen through the lies and propaganda, who have joined the dots to make out the shape of the long-term plan being imposed on us by duplicitous means.

We are described as “conspiracy theorists”, which apparently automatically means we are “far right”. Our commitment to truth and freedom is interpreted as “hate” and identifying the leading role of the Rothschilds in the criminocratic empire amounts, necessarily it seems, to so-called “anti-semitism”.

The reality is, of course, very different. It is that control of our national and international institutions, as well as of the entire industrial-financial system, has fallen, by foul means, into the hands of a veritable mafia.

Because this global domination is profoundly anti-democratic and entirely illegitimate – based as it is on criminal activity and the concealment of that wrong-doing – it has to be kept secret.

The criminocracy knows that there can never be clear-sighted and united opposition to its rule while people remain trapped in its tricks and illusions and fail to even recognise its existence, let alone start talking about how to bring it down.

Our most important first task is therefore to expose its activities, to break down the multiple walls of its defences, to ignore its threats and taboos and to shout from the rooftops what it is and what it is doing to us.

Subscribe to Paul Cudenec

NOTES

For more detailed discussion of these subject matters, and full references, see my essay ‘A crime against humanity: The Great Reset of 1914-1918’ and my booklet Enemies of the People: The Rothschilds and their corrupt global empire.

[1] Klaus Schwab, Thierry Malleret, Covid-19: The Great Reset (Geneva: WEF, 2020), e-book. Edition 1.0, 63%.

[2] Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor, Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War (Edinburgh & London: Mainstream Publishing, 2013), p. 139.

[3] Jim Macgregor and Gerry Docherty, Prolonging the Agony: How the Anglo-American Establishment Deliberately Extended WWI by Three-and-a-Half Years (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2018), p. 233.

[4] George H Nash, Herbert Hoover The Great Humanitarian 1914-1917, p. x, cit. Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 202.

[5] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 204.

[6] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, pp. 204-05.

[7] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 229.

[8] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 231.

[10] https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/09/business/09rothschild.html

[11] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9309/

[12] Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: The World’s Greatest

Banker 1849-1999 (New York: Penguin, 2000), p. 89.

[13] Ferguson, p. 205.

[14] Schwab, 89%, 90%

0 Comments