America’s Death Squads: When Police Become Judge, Jury and Executioner

By John W. Whitehead & Nisha Whitehead | Oct 11, 2022

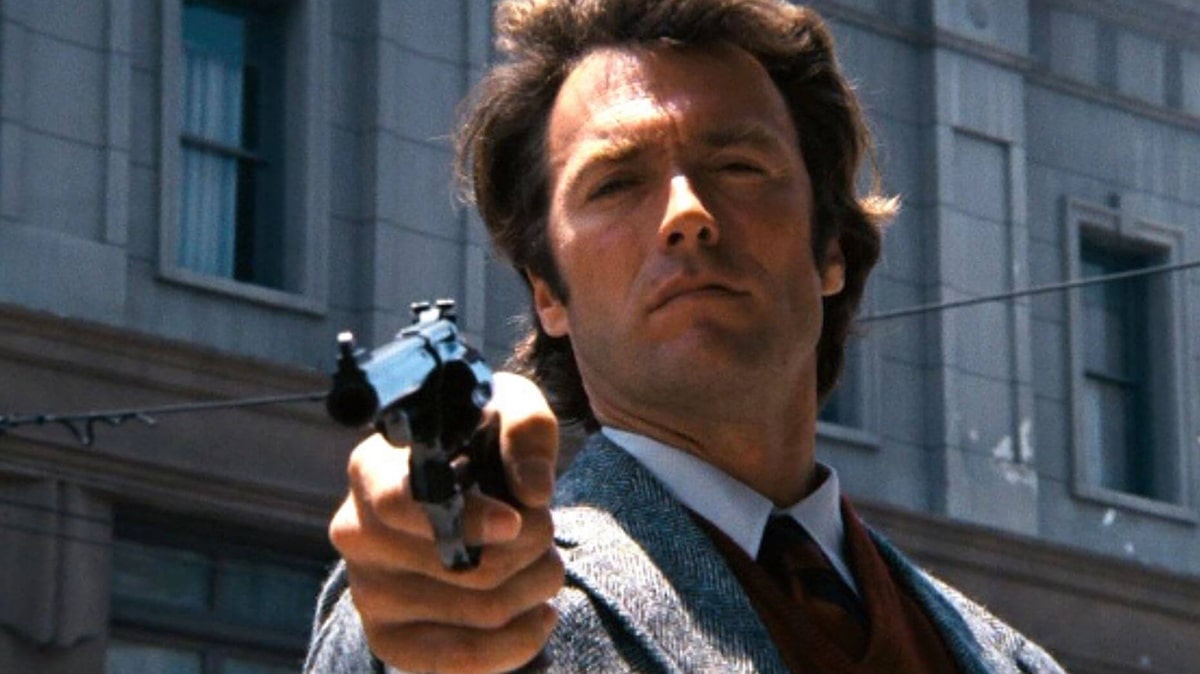

“You know, when police start becoming their own executioners, where’s it gonna end? Pretty soon, you’ll start executing people for jaywalking, and executing people for traffic violations. Then you end up executing your neighbor ‘cause his dog pisses on your lawn.”—“Dirty Harry” Callahan, Magnum Force

When I say that warrior cops—hyped up on their own authority and the power of the badge—have not made America any safer or freer, I am not disrespecting any of the fine, decent, lawful police officers who take seriously their oath of office to serve and protect their fellow citizens, uphold the Constitution, and maintain the peace.

My concern rests with the cops who feel empowered to act as judge, jury and executioner.

These death squads believe they can kill, shoot, taser, abuse and steal from American citizens in the so-called name of law and order.

Just recently, in fact, a rookie cop opened fire on the occupants of a parked car in a McDonald’s parking lot on a Sunday night in San Antonio, Texas.

The driver, 17-year-old Erik Cantu and his girlfriend, were eating burgers inside the car when the police officer—suspecting the car might have been one that fled an attempted traffic stop the night before—abruptly opened the driver side door, ordered the teenager to get out, and when he did not comply, shot ten times at the car, hitting Cantu multiple times.

Mind you, this wasn’t a life-or-death situation.

It was two teenagers eating burgers in a parking lot, and a cop fresh out of the police academy taking justice into his own hands.

This wasn’t an isolated incident, either.

In Hugo, Oklahoma, plain clothes police officers opened fire on a pickup truck parked in front of a food bank, heedless of the damage such a hail of bullets—26 shots were fired—could have on those in the vicinity. Three of the four children inside the parked vehicle were shot: a 4-year-old girl was shot in the head and ended up with a bullet in the brain; a 5-year-old boy received a skull fracture; and a 1-year-old girl had deep cuts on her face from gunfire or shattered window glass. The reason for the use of such excessive force? Police were searching for a suspect in a weeks-old robbery of a pizza parlor that netted $400.

In Minnesota, a 4-year-old girl watched from the backseat of a car as cops shot and killed her mother’s boyfriend, Philando Castile, a school cafeteria supervisor, during a routine traffic stop merely because Castile disclosed that he had a gun in his possession, for which he had a lawful conceal-and-carry permit. That’s all it took for police to shoot Castile four times as he was reaching for his license and registration.

In Arizona, a 7-year-old girl watched panic-stricken as a state trooper pointed his gun at her and her father during a traffic stop and reportedly threated to shoot her father in the back (twice) based on the mistaken belief that they were driving a stolen rental car.

This is how we have gone from a nation of laws—where the least among us had just as much right to be treated with dignity and respect as the next person (in principle, at least)—to a nation of law enforcers (revenue collectors with weapons) who treat the citizenry like suspects and criminals.

The lesson for all of us: at a time when police have almost absolute discretion to decide who is a threat, what constitutes resistance, and how harshly they can deal with the citizens they were appointed to “serve and protect”—and a “fear” for officer safety is used to justify all manner of police misconduct—“we the people” are at a severe disadvantage.

Add a traffic stop to the mix, and that disadvantage increases dramatically.

According to the Justice Department, the most common reason for a citizen to come into contact with the police is being a driver in a traffic stop.

On average, one in 10 Americans gets pulled over by police.

Of the roughly 1,100 people killed by police each year, 10% of those involve traffic stops.

Historically, police officers have been given free range to pull anyone over for a variety of reasons.

This free-handed approach to traffic stops has resulted in drivers being stopped for windows that are too heavily tinted, for driving too fast, driving too slow, failing to maintain speed, following too closely, improper lane changes, distracted driving, screeching a car’s tires, and leaving a parked car door open for too long.

Motorists can also be stopped by police for driving near a bar or on a road that has large amounts of drunk driving, driving a certain make of car (Mercedes, Grand Prix and Hummers are among the most ticketed vehicles), having anything dangling from the rearview mirror (air fresheners, handicap parking permits, toll transponders or rosaries), and displaying pro-police bumper stickers.

Incredibly, a federal appeals court actually ruled unanimously in 2014 that acne scars and driving with a stiff upright posture are reasonable grounds for being pulled over. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that driving a vehicle that has a couple air fresheners, rosaries and pro-police bumper stickers at 2 MPH over the speed limit is suspicious, meriting a traffic stop.

Equally appalling, in Heien v. North Carolina, the U.S. Supreme Court—which has largely paved the way for the police and other government agents to probe, poke, pinch, taser, search, seize, strip and generally manhandle anyone they see fit in almost any circumstance—allowed police officers to stop drivers who appear nervous, provided they provide a palatable pretext for doing so.

Black drivers are almost two times more likely than white drivers to be pulled over by police and three times more likely to have their vehicles searched. As the Washington Post concludes, “‘Driving while black’ is, indeed, a measurable phenomenon.”

In other words, drivers beware.

Traffic stops aren’t just dangerous. They can be downright deadly.

Patrick Lyoya was pulled over for having a mismatched license plate. The unarmed man was shot in the back of the head while on the ground during a subsequent struggle with a Michigan police officer.

Reportedly pulled over for a broken taillight, Walter Scott—unarmed—ran away from the police officer, who pursued and shot him from behind, first with a Taser, then with a gun. Scott was struck five times, “three times in the back, once in the upper buttocks and once in the ear — with at least one bullet entering his heart.”

Samuel Dubose, also unarmed, was pulled over for a missing front license plate. He was reportedly shot in the head after a brief struggle in which his car began rolling forward.

Levar Jones was stopped for a seatbelt offense, just as he was getting out of his car to enter a convenience store. Directed to show his license, Jones leaned into his car to get his wallet, only to be shot four times by the “fearful” officer. Jones was also unarmed.

Bobby Canipe was pulled over for having an expired registration. When the 70-year-old reached into the back of his truck for his walking cane, the officer fired several shots at him, hitting him once in the abdomen.

Dontrell Stevens was stopped “for not bicycling properly.” The officer pursuing him “thought the way Stephens rode his bike was suspicious. He thought the way Stephens got off his bike was suspicious.” Four seconds later, sheriff’s deputy Adams Lin shot Stephens four times as he pulled out a black object from his waistband. The object was his cell phone. Stephens was unarmed.

That police are choosing to fatally resolve these encounters by using their guns on fellow citizens speaks volumes about what is wrong with policing in America today, where police officers are being dressed in the trappings of war, drilled in the deadly art of combat, and trained to look upon “every individual they interact with as an armed threat and every situation as a deadly force encounter in the making.”

Keep in mind, from the moment those lights start flashing and that siren goes off, we’re all in the same boat. Yet it’s what happens after you’ve been pulled over that’s critical.

Trying to predict the outcome of any encounter with the police is a bit like playing Russian roulette: most of the time you will emerge relatively unscathed, although decidedly poorer and less secure about your rights, but there’s always the chance that an encounter will turn deadly.

Survival is key.

Technically, you have the right to remain silent (beyond the basic requirement to identify yourself and show your registration). You have the right to refuse to have your vehicle searched. You have the right to film your interaction with police. You have the right to ask to leave. You also have the right to resist an unlawful order such as a police officer directing you to extinguish your cigarette, put away your phone or stop recording them.

However, there is a price for asserting one’s rights. That price grows more costly with every passing day.

If you ask cops and their enablers what Americans should do to stay alive during encounters with police, they will tell you to comply, cooperate, obey, not resist, not argue, not make threatening gestures or statements, avoid sudden movements, and submit to a search of their person and belongings.

Unfortunately, in the American police state, compliance is no guarantee that you will survive an encounter with the police with your life and liberties intact.

Every day we hear about situations in which unarmed Americans complied and still died during an encounter with police simply because they appeared to be standing in a “shooting stance” or held a cell phone or a garden hose or carried around a baseball bat or answered the front door or held a spoon in a threatening manner or ran in an aggressive manner holding a tree branch or wandered around naked or hunched over in a defensive posture or made the mistake of wearing the same clothes as a carjacking suspect (dark pants and a basketball jersey) or dared to leave an area at the same time that a police officer showed up or had a car break down by the side of the road or were deaf or homeless or old.

More often than not, it seems as if all you have to do to be shot and killed by police is stand a certain way, or move a certain way, or hold something—anything—that police could misinterpret to be a gun, or ignite some trigger-centric fear in a police officer’s mind that has nothing to do with an actual threat to their safety.

Now politicians, police unions, law enforcement officials and individuals who are more than happy to march in lockstep with the police state make all kinds of excuses to justify these shootings. However, to suggest that a good citizen is a compliant citizen and that obedience will save us from the police state is not only recklessly irresponsible, but it is also deluded.

To begin with, and most importantly, Americans need to know their rights when it comes to interactions with the police, bearing in mind that many law enforcement officials are largely ignorant of the law themselves.

A good resource is The Rutherford Institute’s “Constitutional Q&A: Rules of Engagement for Interacting with Police.”

In a nutshell, the following are your basic rights when it comes to interactions with the police as outlined in the Bill of Rights:

You have the right under the First Amendment to ask questions and express yourself. You have the right under the Fourth Amendment to not have your person or your property searched by police or any government agent unless they have a search warrant authorizing them to do so. You have the right under the Fifth Amendment to remain silent, to not incriminate yourself and to request an attorney. Depending on which state you live in and whether your encounter with police is consensual as opposed to your being temporarily detained or arrested, you may have the right to refuse to identify yourself. Not all states require citizens to show their ID to an officer (although drivers in all states must do so).

As a rule of thumb, you should always be sure to clarify in any police encounter whether or not you are being detained, i.e., whether you have the right to walk away. That holds true whether it’s a casual “show your ID” request on a boardwalk, a stop-and-frisk search on a city street, or a traffic stop for speeding or just to check your insurance. If you feel like you can’t walk away from a police encounter of your own volition—and more often than not you can’t, especially when you’re being confronted by someone armed to the hilt with all manner of militarized weaponry and gear—then for all intents and purposes, you’re essentially under arrest from the moment a cop stops you. Still, it doesn’t hurt to clarify that distinction.

While technology is always going to be a double-edged sword, with the gadgets that are the most useful to us in our daily lives—GPS devices, cell phones, the internet—being the very tools used by the government to track us, monitor our activities, and generally spy on us, cell phones are particularly useful for recording encounters with the police and have proven to be increasingly powerful reminders to police that they are not all powerful.

Knowing your rights is only part of the battle, unfortunately.

As I point out in my book Battlefield America: The War on the American People and in its fictional counterpart The Erik Blair Diaries, the danger arises when the burden of proof is reversed, “we the people” are assumed guilty, and we have to exercise our rights while simultaneously attempting to prove our innocence to trigger-happy cops with no understanding of the Bill of Rights.

0 Comments