Are “Payment Strikes” About to Become a Regular Feature of the Economic Landscape?

by | Aug 23, 2022

The reemergence of “payment strikes” is perhaps a sign that as economic conditions deteriorate, people will begin to leverage the only real power they have left in today’s hyper-consumerist societies — i.e., as consumers.

In 1990, British people did the most unBritish of things — they revolted en masse against a deeply unpopular government policy. Across the country, beginning in Scotland, hundreds of thousands of people rioted against the Thatcher government’s poll tax, which was levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual, regardless of income, resources or ability to pay. Households covering almost a third of the British population initially refused to pay the tax even though such an act could lead to prosecution. It was the largest payment strike of modern British history and ultimately sowed the seeds of Margaret Thatcher’s downfall.

Now, the UK may be about to see another, albeit very different, mass payment strike. In response to runaway energy price rises, a seemingly grassroots movement called Don’t Pay UK, modelling itself on the poll tax resistance, has called on one million of the UK’s 28 million electricity consumers to boycott the energy companies this Fall. Formed in June, the campaign has already gathered over 110,000 pledges not to pay energy bills after October 1, unless the government and large energy companies reduce bills to an affordable level.

The goal of Don’t Pay UK is simple, says the campaign’s website:

We are demanding a reduction of energy bills to an affordable level. Our leverage is that we will gather a million people to pledge not to pay if the government goes ahead with another massive hike on October 1st.

Mass non-payment is not a new idea, it happened in the UK in the late 80s and 90s, when more than 17 million people refused to pay the Poll Tax – helping bring down the government and reversing its harshest measures.

Even if a fraction of those of us who are paying by direct debit stop our payments, it will be enough to put energy companies in serious trouble, and they know this.

We want to bring them to the table and force them to end this crisis.

Even by European standards, energy prices have soared for British households over the past year. In April, the UK’s Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem)– tasked with overseeing the country’s privatized grid — hiked its price cap on energy bills (the maximum amount energy suppliers can charge each year) by 54% to £1,971. The next price cap, for October, is due to be published this Friday. Energy market intelligence consultancy Cornwall Insight has forecast it could rise by as much as 70%, taking the cap to an estimated £3,582 a year for a typical home.

From October, the price caps will change every three months instead of every six, opening the way to more regular price rises in the future. Ofgem may raise the price cap to £4,266 in January, says Cornwall Insight and to over £5,000 in April, according to Citi’s estimates.

That would represent a more than four-fold increase in energy bills in the space of just one year, at a time when most people — particularly those at the lower levels of the income scale — have seen their real salaries fall sharply. To make matters worse, as the British chartered accountant and political economist Richard Murphy notes in a piece for The Scotsman, the burden of the price rises will fall disproportionately on lower income households:

Whilst the top 20 per cent might see [energy] inflation of about seven per cent in the UK, those in the lowest twenty per cent of income earners could experience energy inflation of around 16 per cent, in the IMF’s estimation…

But why has the price for those on low incomes increased so disproportionately?

First, many in this group are forced onto pre-paid meters. Second, these have the worst tariffs. And third, the standing charges for simply having any meter in your house are disproportionately high for those on low incomes because, relatively, they consume less energy, and those standing charges have increased considerably.

There is plenty that both the government and Ofgem could do to relieve the pressure on the most vulnerable households if they wanted to, says Murphy, including scrapping the standing charge and including it in the tariff, making charges progressive to ensure that the more energy a household consumes the more they proportionately pay for that energy, and requiring that pre-paid users, who are normally on the lowest incomes, pay the lowest tariffs.

But none of these are likely to happen. Despite the gravity of the situation, with as many as two-thirds of British families and over 85% of pensioners expected to slip into fuel poverty – where at least 10% of net income is spent on fuel – by January, there is still no meaningful help on offer from the UK’s rudderless government. At the same time, many of the UK’s largest energy companies are recording bumper profits.

But hard-up consumers may end up taking matters into their own hands. And in the UK, where credit card debt is up a third in the last year, the mandatory state pension is among the lowest in Western Europe and inflation could soon hit 18%, the highest level in 50 years, they are legion.

So far, 110,000 have pledged not to pay their direct debit bill in October unless the government and energy companies drastically reduce prices. This is despite dire warnings of serious consequences from the government, charities, unions and the media. As FT Advisor notes, the protestors risk damaging their credit histories which will mean any borrowing, whether for a mortgage, personal loan or credit card, will be at a higher interest rate. Energy companies can also add interest to the debt. Worse still, non-paying customers could be forced onto much more expensive pre-pay schemes or have their energy supply disconnected, though this is “very rare”, says Citizen Advice Bureau.

The organizers of Don’t Pay UK say that if it is unable to gather a million pledges, it will call off the strike. But the pressure may already be having some effect. As the Guardian reported yesterday, the UK Treasury has agreed to work closely with energy firms in the coming weeks to ensure the public are supported in the face of rising costs, though it did not not set out what that would entail.

Mortgage Payment Strike Wreaks Havoc in China

China is already witnessing a full-fledged payment strike that is causing havoc for some of the country’s lenders and many of its embattled real estate developers. The fact this is happening amid an acute property downturn, with sales forecast to drop by as much as a third this year, hardly helps matters.

The initial inspiration for the mortgage boycott appears to be a series of protests between April and June against the freezing of roughly 40 billion renminbi (or about $6 billion dollars) of retail deposits at rural banks in Henan Province. In early-to-mid July, an online crowdsourcing group (“WeNeedHomes”) began grumbling about the failure of property developers to deliver apartments on schedule, despite the fact they had taken out — and were, at least at that point, still servicing — mortgages to pay for these as-yet-unbuilt apartments.

After WeNeedHomes followed through on its threat to withhold mortgage payments, the mortgage payment strike went viral, quickly becoming a national phenomenon. As Michael Pettis notes in a paper for Carnegie Endowment, by late July more than 320 projects in a multitude of cities were affected by the mortgage boycott. Pettis cites a report by Caixin, which lays out some of the “peculiarities” of the pre-sales process in China:

Although developers in many countries are allowed to sell homes before they finish building them, the practice in China is special in two ways. First, homebuyers have to pay in full when they decide to buy. Usually, they produce a downpayment for a mortgage and the bank covers the rest. But in other countries like the UK, buyers of presale homes only need to come up with a deposit to reserve a property. They don’t need to pay off a mortgage until their homes are delivered. This full-payment requirement has helped developers raise cash quickly, which they have burned to fund land purchases or expand their business, analysts said.

Second, until recently, Chinese developers had been allowed to use the bulk of their presale revenue for whatever they wanted. Although China has laws and regulations requiring developers to set aside enough money to finish construction on their housing projects, local governments and banks had allowed them to sidestep some of the rules, including the requirement that presale funds must be deposited into government-supervised escrow accounts. Instead, a vast amount of presale funds ended up in developers’ own accounts.

Since the default of China’s largest (and most indebted) real estate developer, Evergrande, in December 2021, fears about the health of other real estate developers have spread across the industry. And apparently with good reason: some 28 of the top 100 developers by sales have either defaulted on bonds or negotiated debt extensions with creditors over the past year, according to Teneo. China’s largest developer, Country Garden just reported a 70% slide in first half profits this year. Of course, rising fears about the health of China’s giant property sector — far and away the largest on the planet — have merely compounded the problem, prompting more and more lenders and investors to withdraw their funding. Now, hundreds of thousands of mortgage holders have done the same.

Given that presales provided a nifty means for developers to obtain cheap financing and, as Pettis points out, was used in an especially aggressive way when liquidity conditions tightened, the withdrawal of some of that funding is likely to be causing serious harm to developers.

Banks and homebuyers “are fighting over which one of them should absorb the losses created by overextended developers, who in turn were overextended because that was the only way to play the property development game successfully,” says Pettis. One way or another, one or other sector of the economy will have to bear the pain of recapitalizing China’s insolvent property developers, “whether it be the household sector, businesses, local governments, Beijing, the agricultural sector, the tradable goods sector, or someone else.”

China’s State Council recently passed a plan to establish a real estate fund worth up to 300 billion renminbi ($44.4 billion) to support at least a dozen property development companies. It has also pledged to provide relief to striking mortgage holders, but so far that relief has been largely insubstantial and temporary, reports South China Morning Post.

The Agricultural Bank of China in Zhengzhou, for example, is allowing some buyers to delay payments for a few months with no penalties or interest, a local account manager with the bank told the Post. After the grace period, homebuyers need to pay double to cover whatever they have skipped.

One unnamed mortgage striker interviewed by SCMP voiced concerns about the potential ramifications that withholding his mortgage payments could have on his credit score, which in turn could impact his daughter’s education. But he remains resolute: “December is the deadline in my mind, as it means that the home has been delayed for a year, and I am paying 4,000 yuan (just under $600) only for some air for almost three years. I have to cut my mortgage as I cannot afford 4,000 yuan for the mortgage and another 3,000 yuan for rent at the same time any longer.”

While the mortgage strike movement is so far relatively small compared to the total market, its growth has raised concerns at top levels of the government. So far, around 2.4 trillion yuan ($356 billion) in mortgage loans are at risk, according to estimates by S&P global. Small local and regional banks are particularly vulnerable, largely due to their outsized exposure to distressed developers.

Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay in USA

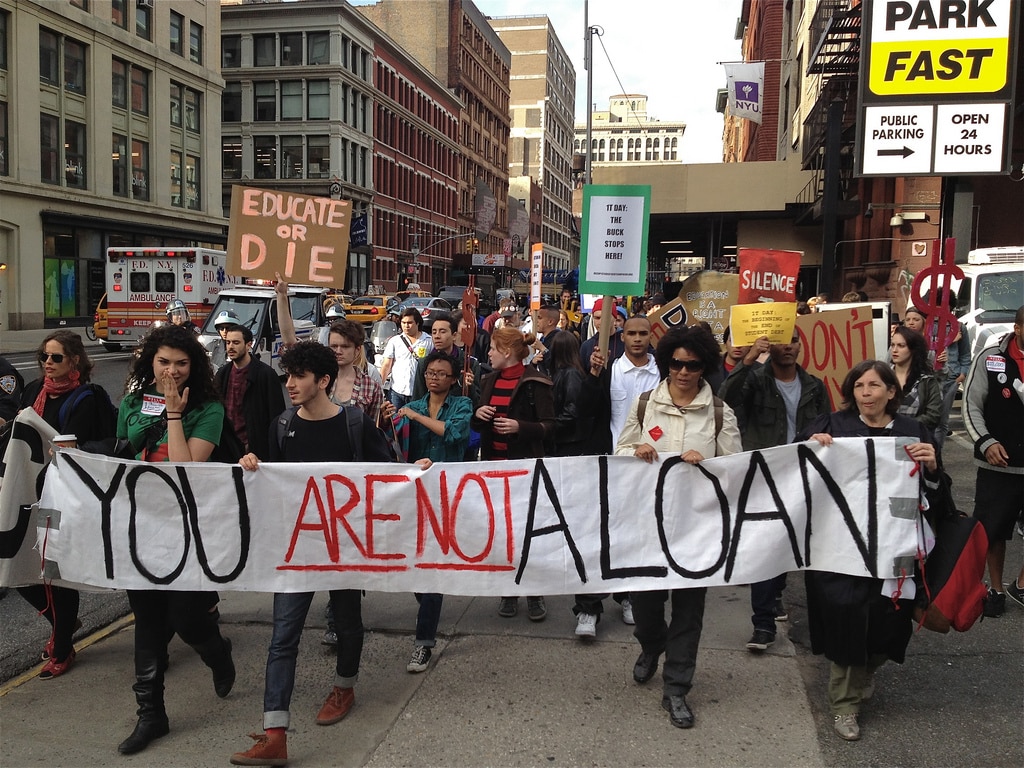

Another country where debtors are threatening to stop paying their debt is the US, where activists belonging to the Debt Collective, a debtors’ union dedicated to ending student debt, have threatened to go on strike if Joe Biden doesn’t deliver on his pledge to provide debt relief to the 45 million Americans who hold student debt. Borrower balances have effectively been frozen since the COVID-19 pandemic, but the moratorium on $1.6 trillion of student loans is set to expire on August 31.

On the campaign trail Biden had promised to cancel at least $10,000 per borrower, but has so far done taken only small targeted measures, such as cancelling debt for students of now-defunct educational institutions and temporarily expanding the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, which forgives the debt of government and non-profit workers after 10 years of payments. But it falls far short of his campaign pledges.

“To highlight the destructive impact of student debt on older Americans,” 50 student debtors over the age of 50 highlight will begin striking in September, the Debt Collective said in a press release. Many of them have already paid tens of thousands of dollars in debt payments yet the principle remains higher today than at the loan’s inception.

The strike will form part of a larger effort by the Debt Collective to stir as many borrowers as possible to withhold their student loan payments. This doesn’t entail defaulting on payments, the group says, which has unpleasant long-term side effects for student debtors. Instead, the group encourages borrowers to take every step possible to shrink their regular payments to $0, such as through public service student loan forgiveness, by applying for waivers for people who have debt from predatory for-profit schools, or other methods.

Granted, a 50-people debt boycott is unlikely to make big waves but if the Biden government were to let the moratorium expire without taking broader action on student debt, which is unlikely given the fast-approaching mid-terms, many more student debtors could end up joining the debt strike, for the simple reason that they are not in a financial position to continue servicing their debt. A survey earlier this year found that 89% of full-time employed student loan borrowers are not financially secure enough to recommence payments, and the recent months of high inflation are unlikely to have eased this problem.

Mexico’s Water Crisis

In neighboring Mexico, local politicians in Puebla have announced plans to organize popular assemblies to urge local citizens to stop paying their water bills after the city council voted to allow the private water supplier to raise water rates. The water supplier plans to hike rates by 4-7% in the coming months and will be able to adjust its charges as often as it wants, which is “totally irregular” for a public service, says Francisco Vélez Pliego, the director of the Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities of the Autonomous University of Puebla (UAP).

This is happening as Mexico’s water crisis escalates. Even as drought grips vast swathes of northern Mexico, drink manufacturers, including Heineken and Coca Cola, continue to extract over a billion liters of groundwater for their bottling plants in Monterrey. As Kurt Hackbarth documents in Jacobin, water in Mexico has long been “transformed from a public resource into a commodity to be sold for profit. It means that corporations can consume water in high quantities while people lack basic access to drinking water.”

As with all four of the payment strikes highlighted in this article (and I presume similar movements are taking place in other countries), there is an overwhelming sense of desperation as people find themselves trapped in systems that no longer serve their interests, if they ever did, and which are fast breaking down, if they haven’t already. Stripped of their power as workers and much of their influence as voters (in China’s one party state, of course, there are no voters), the emergence of payment boycotts is perhaps a sign that as economic conditions deteriorate, desperate people will begin to leverage the only real power they have left in today’s hyper-consumerist societies — i.e., as consumers.

0 Comments