Consumerism Gone Mad

by Roman Bystrianyk | Jan 04, 2025

The greatest blessings of mankind are within us and within our reach.

A wise man is content with his lot, whatever it may be, without wishing for what he has not.– Seneca

Nothing is sufficient for the person who finds sufficiency too little.

– Epicurus

Happiness

We all want to be happy with a life of satisfaction and a feeling of general well-being. It’s something that has been sought after by humanity throughout history. “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” is even enshrined in the United States Declaration of Independence as an “unalienable” right.

In Western civilization, this quality of life for many was undreamed of only a century ago. Before the early twentieth century, people longed for decent housing, clean water, sanitation, safe and hygienic workplaces, child labor laws, schools for their children, shorter workdays, and other basics to make life healthy and enjoyable. As Western societies have progressed, technological advancements and improved social structures changed life from this once abysmal drudgery and struggle to happier and more stable circumstances for millions of people.

One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She is 51 inches high, and has been in the mill for one year. Sometimes she works at night; runs 4 sides and earns 48 cents a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, “I don’t remember”, then confidentially, “I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same.” Out of 50 employees, ten are children about her size.

Since that time of wondrous transformation, there has been an explosion in the availability of consumer products. People are blasted with an almost continual onslaught of advertisements in an attempt to persuade them that buying a wider variety of different products will bring more joy into their lives. The goal is to convince the consumer that the newer, bigger television with more features, the latest fashion trend, the more expensive car, the ever-expanding oversized house, the better cell phone, that latest technological gadget, or the extravagant meal at a trendy restaurant will provide that ultimate fulfillment.

In the United States, the average child sees between 50 and 70 commercials daily on television, and the average adult sees 60 minutes of advertisements and promotions daily.[i] About $150 billion annually is spent to embed consumer advertisements in every conceivable space. The message is clear. You can have a “good life” by making lots of money and spending it on products claiming to make us all happy, loved, and esteemed.[ii]

The preoccupation with consumption as a path to happiness had its roots in stimulating economic profits. American business leaders knew that people could be convinced that, however much they had, it would never be enough.[iii] President Herbert Hoover’s Committee report on the economy published in 1929 exemplified the attitude that the public had to be manipulated to create the desire for more products to spur economic growth.

“Wants are almost insatiable. One want satisfied makes way for another… We have a boundless field before us; there are new wants that will make way endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied… by advertising and other promotional devices, by scientific fact finding, by a carefully predeveloped consumption, a measurable pull on production has been created… it would seem that we can go on with increasing activity.”[iv]

Austrian-American Edward Bernays is known as the father of public relations, a term he invented because it sounded more agreeable than referring it to as propaganda. In the early 1900s, he became an expert in influencing consumer behavior by what he called the “engineering of consent.” He pioneered the mass marketing of fashion, food, soap, cigarettes, books, and a multitude of other consumer products.[v] In his seminal work, Propaganda, he stated his belief that,

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society… We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of… In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons… who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.[vi]

Bernays and others left behind a terrible legacy. They used psychology to create an insatiable consumer demand that drives the throwaway-culture-based economic system we live with today. We live in a society where we are frequently seduced into buying a great deal of meaningless junk, which generally doesn’t bring true happiness but does create lots of waste and debt. Today, many Americans are widely convinced that they need more to be happy, and they work long hours to fulfill these mostly artificially induced desires.

Keeping Up with the Joneses comic strip is a domestic comedy following a family of social climbers, the McGinises, that ran from 1913 to 1938.

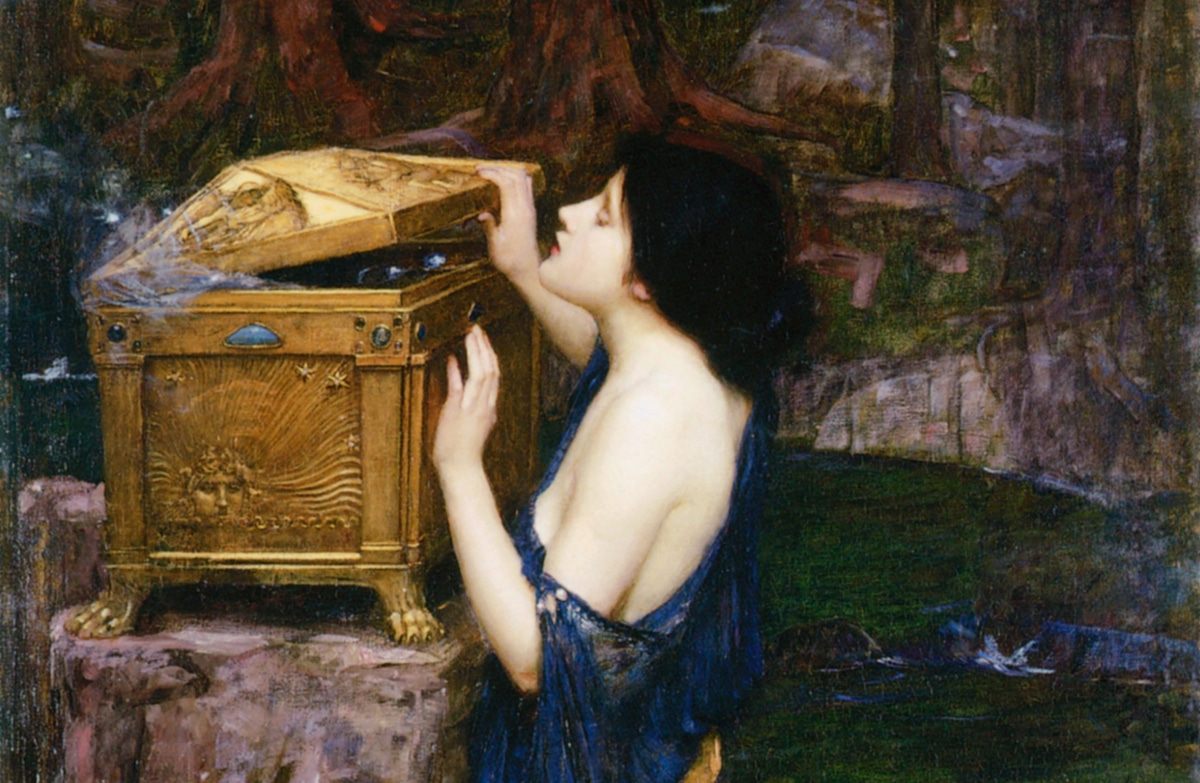

Most advertising is repetitive and misleading, sowing anxieties often by “subtle cinematic and psychological techniques concealed from the consumer.”[vii] Advertising strategies not only promote a particular product but also result in the growth of status restlessness and material consumption as natural and permanent aspects of society. The modern phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” represents the anxiety of failing to meet the same socio-economic status as your neighbors. That expression originated from an early twentieth-century comic strip of the same name.

Buy things for every occasion. Buy things to celebrate. Buy things to mourn. Buy things to keep up with the trends. Buy things while you’re buying things, and then buy a couple more things after you’re done buying things. If you want it — buy it. If you don’t want it — buy it. Don’t make it — buy it. Don’t grow it — buy it. Don’t cultivate it — buy it. We need you to buy. We don’t need you to be a human, we don’t need you to be a citizen, we don’t need you to be a capitalist, we just need you to be a consumer, a buyer.[viii]

Today, many own twice as much as Americans in the 1950s. Then, it was typical for a family to have one bathroom or two or three growing children to share a bedroom. The average American house size has more than doubled since then and now averages 2,349 square feet (218 square meters), where each person not only has their own television but also often has a private bathroom.[ix]

Yet, with all this greatly expanded material wealth, well-being has not increased. Ironically, there has actually been an increase in depression and psychological problems. According to Hope College psychologist David G. Myers, Ph.D.,

…our becoming much better off over the last four decades has not been accompanied by one iota of increased subjective well-being.[x]

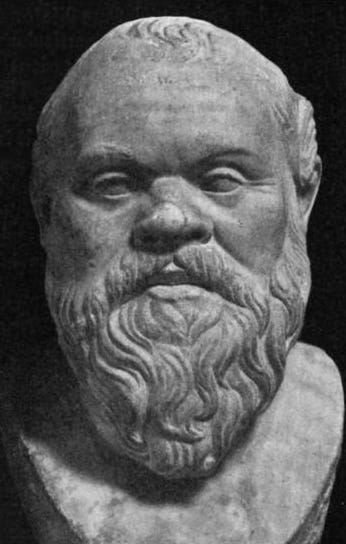

Researchers are reporting that continually buying more can damage relationships and self-esteem and increase anxiety and depression. The stress of working to afford all these material things takes away time from what research shows genuinely makes people happy, like family, friendship, and engaging work.[xi] Socrates, the classical Greek philosopher hailed as one of the most influential thinkers of all time, believed happiness didn’t come from external rewards or accolades but from the private, internal success people bestow upon themselves.[xii] His philosophy and studies show what is essential to happiness and contentment is the polar opposite of today’s pervasive buy-your-way-to-happiness mindset.

The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less. – Socrates

Indeed, to those who are poor or working many hours to make ends meet, more money to afford a comfortable life with adequate housing, food, and clothing makes people more secure and happy. So money contributes to happiness, but only to a certain degree. Beyond that point, there are diminishing returns to where the excesses become unsatisfying. Research consistently shows that the more people value materialistic aspirations and goals, the lower their happiness and life satisfaction. They have also been found to experience fewer pleasant emotions daily.[xiii] Yet materialism is widespread. Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard psychology professor, explains,

If it were the case that money made us totally miserable, we’d figure out we were wrong. But it’s wrong in a more nuanced way. We think money will bring lots of happiness for a long time, and actually, it brings a little happiness for a short time.[xiv]

YouTube, Instagram, and other social media influencers flaunt their large, beautiful, luxurious homes and lavish lifestyles. They promote a culture of consumption, wealth, and privilege that affects the consumption habits of millions who aspire to live this unattainable and unsustainable lifestyle.

Excessive consumerism acts very much like an addictive drug. Purchasing a new and often unneeded thing provides a quick burst of euphoria, which quickly fades, replaced with debt, the extra work hours required to pay it off, and the resulting time away from friends and family.

Exhausted by long hours working and commuting, people begin to wonder what happened to real happiness. Advertisers are there with the answer: You just need to spend still more on plastic surgery, antidepressants, or a new car.[xv]

The unfulfilled promise of bliss by acquiring more possessions is rarely realized because people are inundated with the continual “more is better” message. People become stuck on a psychological treadmill, confident that they will fill their internal void and be happier if only they make just a few more of the right purchases. This is often followed by an emotional letdown as the promise fails to deliver. Then, the cycle repeats. In the end, homes are cluttered with unneeded or even unused purchases, which only amplifies the stress, leaving people feeling even more anxious, helpless, and overwhelmed.[xvi]

Planet trash

Excessive materialism does not fulfill its promise of happiness and has immense societal and ecological burdens. We generally never consider where our possessions come from, what impact manufacturing them has on the world and the people who make these goods, or where they end up when we are done with them.

When people are under the sway of materialism, they also focus less on caring for the Earth. As materialistic values go up, concern for nature tends to go down. Studies show that when people strongly endorse money, image, and status, they are less likely to engage in ecologically beneficial activities like riding bikes, recycling, and reusing things in new ways.[xvii]

Through massive public relations campaigns, industries have fueled binge buying by tapping into primal feelings of fear and desire. Our modern, intense need for material things has fueled not only jobs and economic benefits but also a disposable culture of waste. The estimated amount of garbage The amount of trash humans in the world throw away each year is staggering: 2.1 billion metric tons, equivalent to the weight of 4,200 Burj Khalifas, the world’s tallest building, or over 1.4 billion cars. People in developed countries produce an average of 2.6 pounds (1.1 kilograms) of trash daily. Americans make significantly more trash, at 4.4 pounds (2 kilograms) of daily waste.[xviii]

In a nation of nearly 324 million people, that amounts to more than 700,000 tons of garbage produced daily — enough to fill around 60,000 garbage trucks. The EPA estimates that Americans generated about 254 million tons of garbage in 2013.

More than half the world’s population lives without access to regular trash collection. Trash simply piles up in unregulated or illegal dumpsites, which hold over 40% of the world’s garbage.[xix] In poor countries, waste is often dumped in low-lying areas and land adjacent to slums. Poorly collected or improperly disposed of waste can have a tremendous negative impact on the environment. Potentially infectious medical and hazardous materials can be mixed with garbage, harmful to waste pickers and the environment. Environmental threats include contamination of surface water and groundwater and air pollution from burning waste that is not properly collected and disposed of.

Dumpsites are a global health emergency. The World Health Organization and others calculated that in 2012 exposures to polluted soil, water, and air resulted in an estimated 8.9 million deaths worldwide — 8.4 million of those deaths occurred in low-and middle-income countries. By comparison, HIV/AIDS causes 1.5 million deaths per year and malaria and tuberculosis fewer than 1 million each. More than 1 in 7 deaths are the result of pollution.[xx]

In addition to the toxic environment resulting from the excessive materialism of the world’s wealthy nations, millions of modern-day slaves are used to make items to satiate the demand for cheap products. The global slavery index attempts to measure the scope and scale of slavery on the planet. Their 2018 report indicates that $354 billion of “at-risk” products were imported by the G20 countries.[xxi] The United States is the worst offender, importing $144 billion, three times the second-worst offender, Japan, at $47 billion.

“The prevalence of modern slavery is driven through conflict and oppression, but it’s also derived in more developed countries by consumer demand,” said Fiona David, executive director of research at Walk Free, the organisation that produces the global slavery index.[xxii]

The top five products at risk of modern slavery imported into the G20 are laptops, computers, and mobile phones at $200.1 billion; garments at $127.7 billion; fish at $12.9 billion; cocoa at $3.6 billion, and sugarcane at $2.1 billion. As of 2016, 40.3 million people exist as modern-day slaves, with three-quarters being female. While many slaves are found in impoverished countries, 403,000 people lived in conditions of modern slavery in the United States, a prevalence of 1.3 victims of modern slavery for every thousand in the country.[xxiii]

Wasted food

One thing that is wasted in enormous amounts across the world and that which sustains life is food. Even though there are those in the world who are hungry or starving, there is still a massive amount of food wasted daily. Nearly 800 million people worldwide suffer from hunger. At the same time, about one-third of food is squandered,[xxiv] or about 1.6 billion metric tons (1.76 billion tons) a year, equal to the weight of over 4,800 Empire State Buildings, with a value of about $1 trillion. If this wasted food were stacked in a 20-cubic meter bin, it would fill 80 million of them, enough to reach to the moon and encircle it once. The wasted food is enough to feed the hungry twice over.[xxv]

At least 1.3 billion tons of food is lost or wasted every year — in fields, during transport, in storage, at restaurants, and in markets in industrialized and developed countries alike. In rich countries alone, some 222 million tons of food [are] wasted, which is almost as much as the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa.[xxvi]

There is a vast “farm to the fork to the landfill” problem in the United States, with 40% of food going to waste and the uneaten food ending up rotting in landfills.[xxvii] Roughly 50% of all produce is thrown away, weighing 60 million tons annually, worth $160 billion.[xxviii] Families throw out approximately 25% of the food and beverages they buy.[xxix] One analysis found that students discarded roughly 40% of their fruits and 60 to 75% of their vegetables from their school lunches.[xxx]

It’s not only the wasted food but also all the water, fertilizer, pesticides, seeds, fuel, and land squandered to grow it. Globally, each year, uneaten food utilizes as much water as the entire annual flow of the Volga River, Europe’s most voluminous river.[xxxi]

About one-quarter of produced food is lost along the food-supply chain. The production of this lost and wasted food accounts for 24 percent of the freshwater resources used in food-crop production, 23 percent of total global cropland area, and 23 percent of total global fertilizer use.[xxxii]

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that more food reaches landfills and incinerators than any other single material in our everyday trash, accounting for about 21% of the waste stream.[xxxiii] Food production uses up 10% of the total energy budget, 50% of the land, and 80% of all freshwater consumed.

Growing food releases hundreds of millions of pounds of pesticides into the environment each year, leading to water quality impairment in the nation’s rivers and streams. The energy used from agriculture, transportation, processing, food sales, storage, and preparation to produce the 133 billion pounds of food that retailers and consumers throw out in the United States yearly is massive. It is equivalent to more than 70 times the oil lost in the Gulf of Mexico’s Deepwater Horizon disaster.[xxxiv]

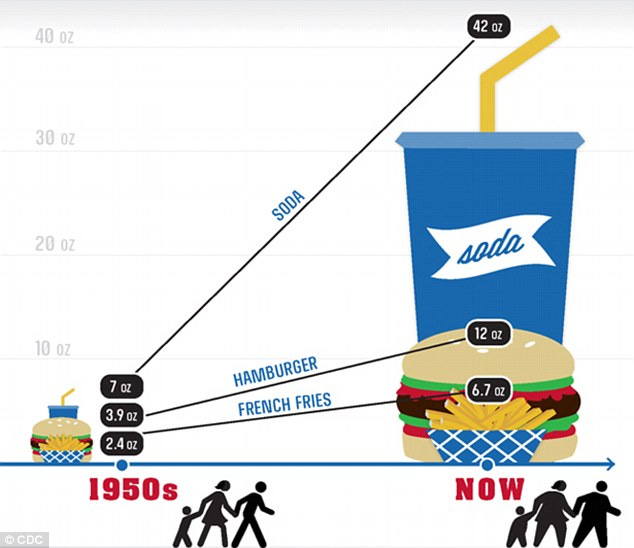

The increase in American food portion sizes over the past 30 years contributed to this food waste culture, which has helped expand food waste and waistlines. Today’s average restaurant portion is more than four times as big as in the 1950s. A cup of soda is now six times as large. Burgers and a portion of fries have both tripled in size. A chocolate bar is over 1,200% larger than in the early 1900s.[xxxv] From 1982 to 2002, the average pizza slice increased by 70% in calories, the standard chicken Caesar salad doubled in calories, and the average chocolate chip cookie quadrupled. Portion sizes can be 2 to 8 times larger than the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) or FDA (United States Food and Drug Administration) standard serving sizes.[xxxvi]

Not only have food portions increased, but the bowls, glasses, and plates have grown to match. In America, the surface area of the average dinner plate has increased by 36% since 1960.[xxxvii] In supermarkets, larger sizes have increased 10-fold between 1970 and 2000.[xxxviii] Larger packages in grocery stores, larger portions in restaurants, and larger kitchenware in homes cause an unconscious perceptual shift that makes people think it is appropriate to eat more than they should.[xxxix]

Since the Great Depression of the 1930s, with its breadlines and food rationing, many in the United States now have easy access to vast amounts of inexpensive food twenty-four hours a day. Not surprisingly, with such an abundance of readily available food, American adults have also increased in size.

Out of control: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released this graphic as part of its The New (Ab)normal campaign. It shows just how meal sizes have increased in the past 60 years.

As of 2018, 42.4% of Americans are now obese. Another 30.7% of adults were categorized as overweight, and 9.2% had severe obesity.[xl] This means that 82.3% of American adults are overweight or heavier. Those with obesity have a higher increased risk of overall mortality, high cholesterol, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, many types of cancer, depression, anxiety, body pain, and difficulty with physical functioning.[xli] As of 2019, 1,408,647 Americans died from heart disease, cancer, and stroke, or on average 3,850 every day.[xlii] Childhood obesity has reached epidemic levels in developed countries. In the United States, 18.5% of children and adolescents are obese, or nearly 1 in 5.[xliii] Medical costs due to obesity are now $190 billion per year, comprising over 21% of all healthcare costs in the country.[xliv]

With increasing portions, Americans are wasting more of the food they buy. The average American wastes 10 times as much food as someone in Southeast Asia, 50% more than Americans in the 1970s.[xlv] Unfortunately, with increasing prosperity comes a generally indifferent attitude towards readily available and easily accessible food. Since, for many people, food represents a small portion of many Americans’ overall budgets, food waste has become relatively unimportant. From an economic perspective, the more food consumers waste, the more profits are to be made by the food industry. Any waste downstream in the food supply chain means more sales and profit for anyone upstream.

American consumers have also come to expect a level of quality in the produce they purchase. A great deal of produce is culled and thrown away if it does not meet specific, unrealistic, and stringent cosmetic standards of size, color, and weight, as well as being free from blemishes.[xlvi]

A large tomato-packing house reported that in mid-season, it can fill a dump truck with 22,000 pounds of discarded tomatoes every 40 minutes. And a packer of citrus, stone fruit, and grapes estimated that 20 to 50 percent of the produce he handles is unmarketable but perfectly edible.

In recent years, supermarkets have started running their produce departments like beauty pageants. They say they are responding to customers who expect only ideal produce.[xlvii] Unfortunately, the demand for “perfect” fruit and vegetables means many are discarded and left in the field to rot, even though blemishes do not necessarily affect freshness or quality. This demand for flawless-looking fruits and vegetables results in as much as half of the food grown in the United States being thrown away.[xlviii]

“It’s all about blemish-free produce,” says Jay Johnson, who ships fresh fruit and vegetables from North Carolina and central Florida. “What happens in our business today is that it is either perfect, or it gets rejected. It is perfect to them, or they turn it down. And then you are stuck.”[xlix]

The discarded food is rarely composted and instead ends up in landfills. Food waste slowly decomposes and releases methane gas, which is considered a greenhouse gas. According to the EPA, methane causes 21 times as much warming as an equivalent mass of carbon dioxide over 100 years. The intensity is much more severe in the first 20 years after its release. During that period, methane is 84 times as potent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide.[l] In the United States, landfills account for about 20% of the total methane emissions.[li] A report from the United Kingdom estimates that the amount of greenhouse gases emitted from food scraps rotting in landfills is equivalent to the emissions of one-fifth of all the country’s cars. If food waste were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest producer of greenhouse gases, after China and the United States.[lii]

Fast fashion

The modern culture of waste is also reflected in cheap clothes. In many industrialized countries, cut-rate clothes are available everywhere. People can select from endless piles of inexpensive jeans, shirts, and other articles of clothing at retail and fast-fashion chain stores. Like food, apparel has, in no small measure, lost any real value. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 1901, clothing accounted for 14% of Americans’ total discretionary expenditures. By 1960, it had decreased to 10.4%; by 2013, it had dropped to 3.1%.[liii]

Because so much clothing can be cheaply purchased, some of it even remains unworn in closets and drawers with the sales tags still attached. In a study of women over the age of 18, the majority admitted that they had never worn at least 20% of the items in their wardrobe.[liv] A survey of 2,000 women found that most clothes were worn only seven times, and a third considered clothes “old” after being worn three times.[lv] One in seven said they were strongly influenced by a social media culture that made it unacceptable to be pictured twice in the same outfit.

In wealthy countries around the world, clothes shopping has become a widespread pastime, a powerfully pleasurable and sometimes addictive activity that exists as a constant hum in our lives, much like social media. The internet and the proliferation of inexpensive clothing have made shopping a form of cheap, endlessly available entertainment—one where the point isn’t what, or even whether, you buy, but the act of shopping itself.[lvi]

Fast and low-cost fashion feeds the immediate gratification process. Each new purchase fires up excitement in the pleasure center in a shopper’s brain with virtually no downside because of such low prices. Stores such as H&M, Forever21, and Zara are only too happy to feed this desire with an almost continuous stream of something new to look at and buy while simultaneously creating enormous profits for the people at the top of these companies. The disposable clothing industry creates demand and continuously churns out massive quantities of cheap clothes. Companies like H&M fuel binging on fashion by supplying cheap items such as women’s T-shirts for $5.99 and boys’ jeans for $9.99.[lvii]

Glossy fashion magazines eagerly declare what fashion trends “are in and out” for every year. At one time, there were the fashion seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter. Today, the fashion industry creates a buzz about 52 “micro-seasons” per year. These new fashion trends that come out every week allow the fashion industry to sell vast quantities of garments as quickly as possible.[lviii]

Along with the push of the fashion industry, the advent of digital technology has made shopping incredibly easy and pleasurable. According to the Urban Land Institute, a survey of millennials (also known as Generation Y) found that 50% of men and 70% of women consider shopping a form of entertainment.[lix] In 1991, the average American bought 34 pieces of clothing a year. By 2007, that number had doubled to 67 items a year, or about one new piece of clothing every five days.[lx]

Fashion is a huge business. In 2012, the global garment market was estimated to be worth $1.7 trillion, employing an estimated 75 million people in 2014.[lxi] China exports 30% of the world’s fast fashion, with Americans buying approximately 1 billion garments yearly, or about four pieces of clothing for every United States citizen.[lxii]

By definition, fast fashion is a phenomenon in the fashion industry in which clothes are designed to be made as quickly and cheaply as possible. These quick and generally poorly made clothes are designed to last as long as the short fashion trend remains. Fast fashion companies profit from a small markup on the hundreds of millions of garments sold yearly. If the outfit quickly falls apart, that only drives the next sale.

“You see some products, and it’s just garbage. It’s just crap,” says Simon Collins, dean of fashion at Parsons The New School for Design, on NPR. “And you sort of fold it up and you think, yeah, you’re going to wear it Saturday night to your party — and then it’s literally going to fall apart.”[lxiii]

This trend of cheap and disposable clothing has become a severe environmental problem, not only in its production but also in the massive quantities thrown out. The Council for Textile Recycling estimates that Americans throw away 32 kilograms (70 pounds) of clothes and other textiles each year. Approximately 10.5 million tons of garments end up in American landfills annually. Each year, over 80 billion pieces of clothing are produced worldwide, with 75% of them ending up in landfills or incinerated.[lxiv] Every second, the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles is dumped into a landfill or incinerated.[lxv]

Secondhand stores receive so much excess clothing that they only resell about 20% of it.[lxvi] Pietra Rivoli, a professor of international business at the McDonough School of Business of Georgetown University, notes that “there are nowhere near enough people in America to absorb the mountains of castoffs, even if they were given away.”

Every article of clothing purchased impacts the planet. The founder of the apparel company that bears her name, Eileen Fisher, has called the clothing industry “the second largest polluter in the world, second only to oil.”[lxvii] The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of humanity’s carbon emissions, producing more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined.[lxviii]

The fashion industry is the second-largest consumer of the world’s water supply.[lxix] In 2015 alone, it consumed 79 billion cubic meters of water, enough to fill 32 million Olympic-size swimming pools.[lxx] That figure is expected to increase by 50% by 2030.

Cotton, used in 40% of all clothing worldwide, is grown on just 2.4% of the world’s cropland, yet it accounts for 24% of global sales of insecticides and 11% of pesticides.[lxxi] More chemical pesticides are used for the growth of cotton than any other crop.

Cotton is a water-intensive crop, taking 2,700 liters (713 gallons) of water to make just one t-shirt[lxxii] or as much as a person would drink throughout three years. The average pair of jeans takes 7,000 liters (1,849 gallons) of water to make, with about 2 billion pairs made every year.[lxxiii] That’s 14 trillion liters (3.7 billion gallons), or enough to fill 5,600 Olympic-size swimming pools.[lxxiv] It takes 20,000 liters (5,290 gallons) of water to produce just one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of cotton.[lxxv]

Only about 1% of cotton grown worldwide is organic.[lxxvi] While organic is much more sustainable than conventional cotton, it still uses vast amounts of water and may even be dyed with chemicals and shipped globally.

The process of dyeing clothes uses 1.7 million metric tons of various chemicals.[lxxvii] Some of the hazardous chemicals used in clothing are alkylphenols, phthalates, brominated and chlorinated flame retardants, azo dyes, organotin compounds, perfluorinated chemicals, chlorobenzenes, chlorinated solvents, chlorophenols, pentachlorophenol (PCP), short-chain chlorinated paraffins, cadmium, lead, mercury, and chromium.

Waste products from a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, spill into a stagnant pond.

According to the American Apparel & Footwear Association, the United States, the world’s largest apparel market, imports over 97% of clothing and 98% of shoes purchased.[lxxviii],[lxxix] Globalization has pushed the manufacturing of cheap clothing to the world’s poorest parts with few, if any, labor laws or environmental regulations.

In Jakarta, Indonesia, the Citarum River is known as the most polluted river in the world. Unregulated factory growth since the 1980s has choked the Citarum with both human and industrial waste. Plastics and other debris float on top of the toxic water filled with dyes and chemicals, including lead, arsenic, and mercury, produced by the over 200 textile factories that line the river.[lxxx] The typically untreated dye wastewater is discharged directly into nearby rivers, eventually reaching the ocean.[lxxxi] More than a half-trillion gallons of fresh water are used in the dyeing of textiles each year.

Made from petrochemicals, polyester and nylon are not biodegradable and flood the earth with plastic microfibers, contaminating the food chain. Clothing made from polyester is estimated to take 200 years to break down in a landfill.[lxxxii] Clothes release half a million metric tons of microfibers into the ocean yearly, equivalent to over 50 billion plastic bottles.[lxxxiii]

Manufacturing synthetic fabrics is an energy-intensive process that takes enormous amounts of crude oil to make. An estimated 70 million barrels of oil are used yearly to produce the virgin polyester used in fabrics.[lxxxiv] A Massachusetts Institute of Technology study calculated that over 706 billion kilograms of greenhouse gas could be attributed to polyester production for use in textiles in 2015.[lxxxv] Those greenhouse gases are equal to the weight of over 471 million cars, over 2,100 Empire State Buildings, and equivalent to the annual emissions of 185 coal-fired power plants. Synthetic materials also emit a large amount of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas, during manufacturing. The impact of one pound of nitrous oxide on global warming is 310 times that of the same amount of carbon dioxide.[lxxxvi]

Cheap clothing has been made possible because of the virtual slave labor in poor countries such as Bangladesh. Over four million people work in Bangladesh’s garment industry, accounting for about 80% of its foreign trade. Ever-decreasing clothing prices driven by fast-fashion chains in the West keep workers’ wages at levels as low as $68 a month or about $2.25 a day.[lxxxvii]

Between 20 to 60% of clothing production is sewn at home. Millions of workers in poor countries are “hunched over, stitching and embroidering the contents of the global wardrobe… in slums where a whole family can live in a single room.”[lxxxviii] Children can work 10 hours a day in harsh conditions to earn a dollar.[lxxxix] Former child factory worker Nazma Akter founded the Awaj Foundation, which fights for labor rights in Bangladesh. Akter noted that the situation for workers had not improved even after the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, where 1,130 people died when a run-down eight-story textile factory complex collapsed.

They have higher production targets. If they cannot fulfill them, they have to work extra hours but with no overtime. It is very tough; they cannot go for toilet breaks or to drink water. They become sick. They are getting the minimum wage as per legal requirements, but they are not getting a living wage… There is too much work pressure, and they have not enough food, and they suffer malnutrition. They spend most of their youth in the garment industry for multinational retailers, and then they have to retire at 40 when their health is ruined.[xc]

Major brands such as Gap, Marks & Spencer, and Adidas use Cambodian sweatshops to stitch their clothing. Garment prices are low in the West because workers, primarily women, will sew for about 50 cents an hour.[xci] Although the legal working age is 15 years old, girls as young as 12 drop out of school and labor in Cambodian factories. According to UNICEF and the International Labor Organization, an estimated 170 million children work in the clothing industry worldwide.[xcii] That number of children equals more than half the entire population of the United States.

Electronic waste

As technical innovation has advanced and global trade has increased, the worldwide quantity of electronic devices has exploded. Electronics are now incorporated into the daily lives of most of the people on the planet. In 2007, Apple’s iPhone sales were 1.4 million worldwide. By 2015, sales had increased by over 16,400%, reaching a whopping 231.2 million.[xciii] Apple is only part of an overall massive smartphone market. Smartphone sales have skyrocketed from 122.3 million in 2007 to over 1.5 billion in 2017.[xciv] Falling prices now make electronic devices affordable for most people worldwide while encouraging early equipment replacement or new acquisitions in wealthier countries. Thousands of people sometimes wait for hours for the latest electronic gadget.[xcv] In 2020, there were 3.5 billion smartphone users.[xcvi]

Enormous amounts of modern gadgets sold—from smartphones to computers to motorized toothbrushes to greeting cards that play music to robot vacuums—are eventually thrown away. People often discard and replace electronics if a device breaks down, slows down, or a newer model is available.

Electronics have always produced waste, but the quantity and speed of discard has increased rapidly in recent years. There was a time when households would keep televisions for more than a decade. But thanks to changes in technology and consumer demand, there is hardly any device now that persists for more than a couple of years in the hands of the original owner.[xcvii]

Discarded televisions, smartphones, solar panels, refrigerators, and many other devices are classified as electronic waste, also known as e-waste. In 2016, 44.7 million metric tons (49 million tons) of e-waste were generated. [xcviii] By 2024, that number had increased to 62 million metric tons (68 million tons).[xcix] The current rate of e-waste is equivalent to throwing out 1,000 laptops every single second.[c]

In 2016 the world generated e-waste – everything from end-of-life refrigerators and television sets to solar panels, mobile phones, and computers—equal in weight to almost nine Great Pyramids of Giza, 4,500 Eiffel Towers, or 1.23 million fully loaded 18-wheel 40-ton trucks, enough to form a line from New York to Bangkok and back.[ci]

In 2016, the worldwide e-waste average was 6.1 kilograms (13.5 pounds) per person or 24.5 kilograms (54 pounds) for a family of four. In the United States or Canada, the figure was 3.3 times higher. This surging global trend makes e-waste the fastest-growing part of the world’s domestic waste stream.[cii] The carbon impact of the entire Information and Communication Industry (ICT), including personal computers, laptops, monitors, smartphones, and servers, is rapidly increasing. In 2007, ICT represented 1% of the carbon footprint, tripled by 2018, and is set to exceed 14% by 2040.[ciii]

Not only are electronics trashed, but all the valuable materials initially mined and procured with them. Metals such as gold, silver, copper, platinum, and palladium thrown out with e-waste were worth $64.61 billion in 2016.[civ] Ruediger Kuehr, head of the United Nations University’s Sustainable Cycles Programme, noted that only 20% of e-waste goes into the official collection and recycling schemes.[cv]

Smartphones are particularly insidious for a few reasons. With a two-year average life cycle, they’re more or less disposable. The problem is that building a new smartphone–and specifically, mining the rare materials inside them–represents 85% to 95% of the device’s total CO2 emissions for two years. That means buying one new phone takes as much energy as recharging and operating a smartphone for an entire decade. [cvi]

Cobalt is used to build rechargeable lithium-ion batteries in smartphones and other electronic devices. Most of the world’s global cobalt production comes from the Katanga region in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The DRC is home to the world’s largest-known cobalt reserves and is responsible for about two-thirds of its cobalt production.[cvii] In 2017, 64,000 metric tons of cobalt were mined, far ahead of the world’s second-largest cobalt producer that year, Russia, with 5,600 metric tons. Some of the cobalt is extracted by artisanal (or informal) miners.[cviii] According to UNICEF, an estimated 40,000 boys and girls work digging for cobalt for electronic devices. Some artisanal miners use chisels and other hand tools to excavate holes tens of meters deep, while others handpick rocks rich in cobalt ore at the surface. What a 13-year-old boy named Arthur, who was a miner from age 9 to 11, said is reminiscent of what Western children experienced a century or so ago,

I worked in the mines because my parents couldn’t afford to pay for food and clothes for me. Papa is unemployed, and mama sells charcoal.

Children endure long hours of up to 12 hours a day working at the mines, hauling back-breaking cobalt loads of between 20 and 40 kilograms (44 to 88 pounds) for $1-2 per day. Many children are frequently ill, inhaling cobalt dust, which can cause hard metal lung disease, a potentially fatal condition. In addition, some children are killed in tunnel collapses, while others are paralyzed or suffer life-changing injuries from accidents.[cix]

Worker at an e-waste recovery site in Guiyu, Guangdong Province, China.

Most e-waste ends up in technology graveyards in poor countries in West Africa and Asia, causing significant environmental pollution and health risks for local populations. Around 41,500 metric tons (45,745 tons) of used electronic items were shipped into Nigeria from Europe and the United States, hidden inside cars, buses, and trucks. Large quantities of photocopiers, smartphones, desktop computers and laptops, kettles, irons, air conditioners, power generators, microwave ovens, washing machines, and electric cookers often end up in open dumpsites.[cx] Electronic products are made up of hundreds of different materials and contain toxic substances such as lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic, and flame retardants. Once in a landfill, these toxic materials seep into the environment, contaminating land, water, and air. Also, devices are often dismantled in primitive conditions, with those who work at these sites suffering frequent bouts of illness.[cxi]

About 70% of globally generated electronic waste ends up in China, primarily through illegal channels.[cxii] Guiyu, in Guangdong Province, China, is possibly the world’s largest e-waste disposal site. In small workshops and the open countryside, thousands of men, women, and children take apart old computers, monitors, printers, DVD players, photocopying machines, telephones and phone chargers, music speakers, car batteries, and microwave ovens, stripping them down to the smallest components.[cxiii] Hundreds of thousands here have become experts at dismantling the world’s discarded electronics.

They use primitive methods that leave them exposed to environmental hazards. For example, circuit boards and other computer parts are burned, individually, over open fires to extract metals. This smelting process releases large amounts of toxic gases into the air. Plastics are graded by quality, and other parts are burned to separate plastic from scrap metal. After this thorough dismembering, any remaining combustibles are left to burn in open fires, filling the air with the acrid stench of plastic, rubber, and paint. [cxiv]

The workers at Guiyu are poor migrants, and they and their children live and work near the smoldering waste that creates clouds of toxic smoke. The groundwater in Guiyu is undrinkable. Streams are black and pungent and choked with industrial waste. The tested streams were found to have acid baths leaching into them, with the water so acidic that it disintegrated a penny after a few hours.[cxv]

Over 95% of the e-waste is treated and processed in the majority of urban slums of the country, where untrained workers carry out the dangerous procedures without personal protective equipment, which are detrimental not only to their health but also to the environment.[cxvi]

Globalization

While globalization seems like a great thing because we can get our products from all over the world, the environmental and health costs are enormous. Your foreign-made creation likely traveled halfway around the world in a container ship fueled by the dirtiest fossil fuels. These ships burn fuel made from the dregs of the oil refining process. Marine heavy fuel, also known as “bunker fuel,” is pitch black, thick as molasses, and has up to 2,000 times the sulfur content of diesel fuel used in the United States and European automobiles. These ships leave behind a trail of potentially lethal chemicals of sulfur and smoke linked to breathing problems, inflammation, cancer, and heart disease.[cxvii] According to a Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) report, one container ship operating along the coast of China emits as much diesel pollution as 500,000 new Chinese trucks in a single day.[cxviii]

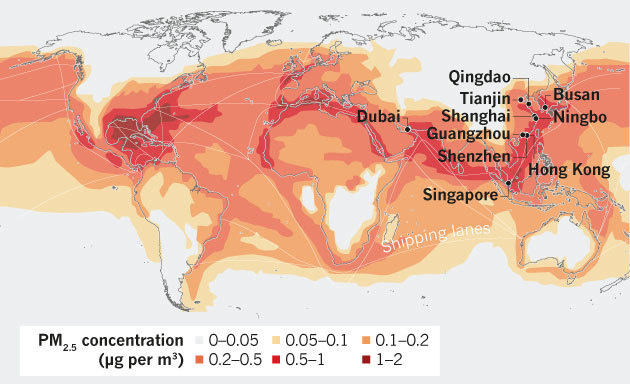

Concentrations of air pollution along global shipping routes. Until recently, most of the world’s 10 busiest ports — nine of which are in Asia — had no limits on emissions. PM2.5 refers to atmospheric particulate matter (PM) that have a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers, which is about 3% the diameter of a human hair.

As populations increase and global economies expand, the amount of cargo that ships transport has vastly increased. From the 1970s to 2016, shipping volumes have increased by 300%, making cargo ships one of the world’s largest sources of air pollution. Ship-related health impacts include approximately 400,000 premature deaths from lung cancer and cardiovascular disease and 14 million childhood asthma cases annually.[cxix] However, as increasing evidence indicates the enormous risks of burning bunker fuel, the global maritime industry is overhauling cargo ship fuel supplies. Starting January 1, 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) required ships to use fuel no more than 0.5% sulfur, down from 3.5%. This is projected to prevent roughly 150,000 premature deaths and 7.6 million childhood asthma cases each year, although it will still result in 250,000 premature deaths and 6.4 million childhood asthma cases.[cxx]

Shipping traffic can also be a significant source of tiny plastic particles that end up in our oceans.[cxxi] Binders, part of marine paint, are applied to the hulls to protect the ships and slowly chip away, resulting in significant ocean pollution. Ships leave microplastic pollution in the water much as tire wear particles from cars are on land.

In the European Union alone, several thousand tons of paint end up in the marine environment every year. With potentially harmful consequences for the environment: coatings and paints used on ships contain heavy metals and other additives that are toxic to many organisms. These antifouling components are used to protect ships’ hulls from barnacles and other subaquatic organisms and are constantly rubbed off by the wind and waves.[cxxii]

Throwaway society

In 1955, LIFE magazine published an article titled “Throwaway Living. Disposable items cut down household chores.” The new promise was that, as a modern society, we didn’t have to be bothered with the mundane chores of cleaning items when those items could just be thrown out. That notion has vastly escalated ever since that time. Our ever-expanding “throwaway living” is characterized by rampant consumerism and the ever-increasing trend to easily discard things and buy something new. With consumers primarily interested in price and quality, environmental and social costs are rarely considered. Industries interested in increasing sales and providing for their customers’ wants also have little incentive to consider those costs. Advertisers who help compel people to purchase things they don’t necessarily need are also oblivious or uncaring to these costs.

1955 LIFE magazine article – “Throwaway Living.” The objects flying through the air in this picture would take 40 hours to clean-except that no housewife need bother. They are all meant to be thrown away after use.

As affluence increases and prices fall, often through the use of cheap labor in countries with lax or nonexistent labor and environmental laws, the actual value of food, clothing, electronics, and other products is lost. With the actual costs of what people buy hidden, it propels the notion that things are disposable. The primarily invisible costs continue to build and magnify, with industries, media, and governments rarely interested in exposing the enormous downsides to a world economic system dependent on growth, waste, and exploitation. Yet this perpetual expansion system of consumption and waste is simply unsustainable and leaves a massive wake of human and environmental destruction. According to Story of Stuff creator Annie Leonard,

It is a linear system, and we live on a finite planet. You cannot run a linear system on a finite planet indefinitely. Too often, the environment is seen as one small piece of the economy. But it’s not just one little thing, it’s what every single thing in our life depends upon.[cxxiii]

Shopping is a way that people often search for themselves and their place in the world. Because people often conflate the search for self with the search for stuff, they ultimately never really find true happiness. The good news is that sustainable happiness is achievable. It could be available to everyone, and it doesn’t have to cost the planet. It turns out that we don’t need to use up and wear out the world in a mad rush to produce the stuff that is supposed to make us happy. We don’t need people working in sweatshop conditions to manufacture cheap stuff to feed an endless appetite for possessions. It begins by assuring that everyone can obtain a basic level of material security, and it requires an understanding that excessive acquisition of things isn’t the path to happiness.

Mindfulness—the focused awareness of the present moment, which can be cultivated through meditation and contemplative practice—may be an effective remedy for empty or compulsive consumption. Research shows that a sense of meaning and deep satisfaction isn’t achieved through mass accumulation; instead, it comes from other sources. We need loving relationships, thriving natural and human communities, meaningful work opportunities, and a few simple practices like gratitude and mindfulness. With that definition of sustainable happiness, we really can have it all.

What you can do!

The human legacy of waste and greed destroys the environment, ruins people’s health, and enslaves others to make cheap products while not increasing happiness for those who are overconsuming. Here are some simple steps that you can take at a personal level to make a difference.

Avoid advertising—Watching television and other media, you are bombarded with advertisements. All these commercials attempt to influence you to purchase products you often don’t need. Turn off the television and avoid ads as much as possible. Anytime you encounter an advertisement, be aware that they are designed to manipulate you to buy their product. Don’t succumb to their often false promises of happiness. Once you are aware of the manipulation, you will be far less susceptible to their influence, which will be better for you and the planet.

Decrease food waste—When food is wasted, all the resources that go into producing, manufacturing, packaging, and transporting it are also squandered. By being aware, only buying the amount you need and cutting down that waste will reduce the amount of land and resources used to grow the food. This will reduce the fertilizers, pesticides, and everything associated with raising that food. As a result, water and land quality improve. Starting your own organic food garden gives you a greater appreciation for food and further reduces waste. Consider creating a compost bin for leftover food scraps. If you go to a restaurant, bring a glass or other container to pack away leftovers and take them home.

Avoid buying new clothing—New clothing takes enormous amounts of resources to produce. Massive quantities of used clothing are available in consignment shops, which are often more unique and generally of superior quality. If you buy new clothes, consider the most sustainable and environmentally friendly materials, such as hemp and bamboo. Maintain your quality clothing by learning how to sow and donating anything you don’t need anymore.

Donate or dispose of electronics properly—If the electronic device is still working, consider donating it to a school, library, or daycare. If the product is at the end of its life, check with e-Stewards or other organizations to properly dispose of it. Always consider repairing instead of replacing if possible.

Donate or dispose of white goods—White goods are large domestic appliances, such as refrigerators or washing machines. They contain significant amounts of metal, plastic, insulating material, refrigerant gases, and other non-renewable and valuable materials. Some charities or furniture reuse organizations accept donations of white goods, and many offer collection services. Recycling keeps these materials in the economy. It also helps prevent toxic substances such as flame-retardants from entering the environment. Check your area for home collection services; shops often collect your unwanted electricals when they deliver a new one.

Use online local buy-sell sites—Many times, items you can no longer use can be utilized by someone else. Reusing items reduces the environmental cost of making new things and the environmental cost of disposing of them. There are websites that promote local buy, sell, and swap online.

Join a local repair café—There are thousands of local repair cafés worldwide. Repair cafes are places where volunteers in the community help you repair household electrical and mechanical devices, computers, bicycles, clothing, and other items. It’s fun, and you can learn how to fix your devices instead of disposing of them.

Avoid novelty electronics—music-playing greeting cards, light-up shoes, LED glasses, smart belts, smart floss dispensers, Bluetooth-enabled “smart forks,” and a device that monitors whether you need to buy more eggs are some of the largely needless novelties and gadgets available to purchase. They are part of an ever-growing number of products of little value but add to the massive amount of e-waste generated. Avoiding these products will reduce pollution and save you money.

Buy the essentials—Too frequently, we buy what we really don’t need, filling our homes with clutter. Taking the time to think about what you really need and avoiding impulse buying will reduce stress on the planet, improve your quality of life, and save you money.

Avoid keeping up with the Joneses—Consumer buying habits on tech have been to dispose of our electronics as soon as they are perceived to be “old.” In the world of tech, that change happens at a very rapid rate. We need to ask ourselves if we are really getting the full lifespan and potential out of our products. Do we really need the newest, smallest, fastest, latest, and greatest, or are we merely suffering from a fear of missing out or not keeping up with others?

The latest fashion trend, the new upgraded technology, or other trendy products impact the environment and cost you money. While a particular product might make you feel better for a short while, in the end, it probably really won’t, leaving you and the planet more impoverished. So carefully consider purchases and why you are buying something. It might be wise to reconsider if buying something is to maintain the same lifestyle as your neighbors or peers.

Find happiness—Happiness comes from within, not from the latest snacks, electronic gadgets, clothing trends, automobiles, or anything else you can buy. You don’t need to compete with your neighbors and friends to get the biggest television or fanciest car. Instead, engage in life by spending time with your family and friends, finding hobbies that interest you, reading and learning, working on your health, volunteering to help those less fortunate than you, creating a piece of art, and involving yourself with many other beneficial activities. Once you break away from the materialistic mindset, you may realize just how trapped you may have been. You can find real happiness, spend less money, and help decrease the enormous stress on our small world.

Roman Bystrianyk’s research and writing are made possible by reader support. To stay informed and help sustain my work, consider subscribing—either for free or with a paid membership. Thank you!

Subscribe to Roman Bystrianyk

References:

[i] Sarah van Gelder, “A Brief History of Happiness: How America Lost Track of the Good Life—and Where to Find It Now,” Yes Magazine, May 15, 2015, http://www.yesmagazine.org/happiness/how-america-lost-track-of-the-good-life-and-where-to-find-it-now

[ii] Tim Kasser, “The High Price of Materialism – how our culture of consumerism undermines our well-being,” https://newdream.org/videos/high-price-of-materialism

[iii] John Buell, Politics, Religion, and Culture in an Anxious Age, 2011, Palgrave Macmillan.

[iv] Sarah van Gelder, “A Brief History of Happiness: How America Lost Track of the Good Life—and Where to Find It Now,” Yes Magazine, May 15, 2015, http://www.yesmagazine.org/happiness/how-america-lost-track-of-the-good-life-and-where-to-find-it-now

[v] Allen J Frances M.D., “How Psychoanalysis and Behaviorism Helped Create Advertising,” Psychology Today, January 9, 2017

[vi] “The manipulation of the American mind: Edward Bernays and the birth of public relations,” The Conversation, July 9, 2015

[vii] John Buell, Politics, Religion, and Culture in an Anxious Age, 2011, Palgrave Macmillan.

[viii] Matt Walsh, “If You Shop on Thanksgiving, You Are Part of the Problem,” Huffington Post, November 20, 2013, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/matt-walsh/shopping-on-thanksgiving_b_4310109.html

[ix] “Behind the Ever-Expanding American Dream House,” NPR, July 4, 2006, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5525283

[x] Tori DeAngelis, “Consumerism and its discontents – Materialistic values may stem from early insecurities and are linked to lower life satisfaction, psychologists find. Accruing more wealth may provide only a partial fix,” American Psychological Association, June 2004, vol. 35, no. 6.

[xi] Carey Goldberg, “Materialism is bad for you, studies say”, New York Times, February 8, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/08/health/materialism-is-badfor-you-studies-say.html

[xii] Weller, Chris, “16 of history’s greatest philosophers reveal the secret to happiness,” Business Insider, October 17, 2016, http://www.businessinsider.com/philosophers-quotes-on-happiness-2016-10

[xiii] Professor of Psychology Tim Kasser, “The High Price of Materialism – how our culture of consumerism undermines our well-being,” https://newdream.org/videos/high-price-of-materialism

[xiv] Carey Goldberg, “Materialism is bad for you, studies say”, New York Times, February 8, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/08/health/materialism-is-badfor-you-studies-say.html

[xv] Sarah van Gelder, “A Brief History of Happiness: How America Lost Track of the Good Life—and Where to Find It Now,” Yes Magazine, May 15, 2015, http://www.yesmagazine.org/happiness/how-america-lost-track-of-the-good-life-and-where-to-find-it-now

[xvi] Sherrie Bourg Carter, “Why Mess Causes Stress: 8 Reasons, 8 Remedies: The mental cost of clutter,” Psychology Today, March 14, 2012, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/high-octane-women/201203/why-mess-causes-stress-8-reasons-8-remedies

[xvii] Professor of Psychology Tim Kasser, “The High Price of Materialism – how our culture of consumerism undermines our well-being,” https://newdream.org/videos/high-price-of-materialism

[xviii] Reynard Loki, “America is a wasteland: The U.S. produces a shocking amount of garbage,” Salon, July 15, 2016, https://www.salon.com/2016/07/15/america_is_a_wasteland_the_u_s_produces_a_shocking_amount_of_garbage_partner

[xix] “Waste Not, Want Not – Solid Waste at the Heart of Sustainable Development,” The World Bank, March 3, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/03/03/waste-not-want-not—solid-waste-at-the-heart-of-sustainable-development

[xx] A Roadmap for closing Waste Dumpsites The World’s most Polluted Places, (ISWA) International Solid Waste Association, September 2012, p. 34.

[xxi] “Global Slavery Index: 2018 Findings,” https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/findings/highlights

[xxii] Annie Kelly, “British public bought £14bn of goods made by slaves in 2017, claims report,” The Guardian, July 18, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jul/19/british-public-14bn-goods-slaves-global-slavery-index

[xxiii] “Global Slavery Index: 2018 Findings Country Studies” United States,” https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/findings/country-studies/united-states

[xxiv] Suzanne Goldenberg, “Half of all US food produce is thrown away, new research suggests,” The Guardian, July 13, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/13/us-food-waste-ugly-fruit-vegetables-perfect

[xxv] Elizabeth Royte, “How ‘Ugly’ Fruits and Vegetables Can Help Solve World Hunger,” National Geographic, March 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/global-food-waste-statistics

[xxvi] Reynard Loki, “America is a wasteland: The U.S. produces a shocking amount of garbage,” Salon, July 15, 2016, https://www.salon.com/2016/07/15/america_is_a_wasteland_the_u_s_produces_a_shocking_amount_of_garbage_partner

[xxvii] Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill, Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012.

[xxviii] Adam Chandler, “Why Americans Lead the World in Food Waste,” The Atlantic, July 15, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/07/american-food-waste/491513

[xxix] Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill, Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012.

[xxx] Ariana Eunjung Cha, “Why the healthy school lunch program is in trouble. Before/after photos of what students ate,” Washington Post, August 26, 2015.

[xxxi] Elizabeth Royte, “How ‘Ugly’ Fruits and Vegetables Can Help Solve World Hunger,” National Geographic, March 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/global-food-waste-statistics

[xxxii] Water pollution from agriculture: a global review – Executive summary, FAO & IWMI, 2017.

[xxxiii] United States 2030 Food Loss and Waste Reduction Goal, EPA (Environmental Protection Agency)

[xxxiv] Elizabeth Royte, “How ‘Ugly’ Fruits and Vegetables Can Help Solve World Hunger,” National Geographic, March 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/global-food-waste-statistics

[xxxv] “How the size of an average restaurant meal has QUADRUPLED since the 1950s – with U.S. burgers now three times as big,” Daily Mail, May 23 2012, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2148970/How-size-average-restaurant-meal-QUADRUPLED-1950s–U-S-burgers-times-big.html

[xxxvi] Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill, Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012.

[xxxvii] Lisa F. Berkman, Ichiro Kawachi, and M. Maria Glymour, Social Epidemiology, Oxford University Press, 2014

[xxxviii] Paul Insel, et al., Nutrition – Fourth Edition, 2011, p. 48.

[xxxix] Brian Wansink, Phd and Koert Van Ittersum, Phd, “Portion Size Me: Downsizing Our Consumption

Norms,” Journal of the American Dieteic Association, July 2007, vol. 107, no. 7, pp. 1103-1106.

[xl] Zeena Mackerdien PhD, “Obesity Rates Continue to Rise Among Americans,” https://www.medpagetoday.org/primarycare/obesity/90456

[xli] “The Health Effects of Overweight & Obesity,” https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html

[xlii] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm

[xliii] Mahshid Dehghan, Noori Akhtar-Danesh and Anwar T Merchant, “Childhood obesity, prevalence and prevention,” Nutrition Journal, September 2005

[xliv] Susan Kelley, “Obesity accounts for 21 percent of U.S. health care costs,” Cornell Chronicle, April 4, 2012, http://news.cornell.edu/stories/2012/04/obesity-accounts-21-percent-medical-care-costs

[xlv] Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill, Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012.

[xlvi] Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill, Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012.

[xlvii] Elizabeth Royte, “How ‘Ugly’ Fruits and Vegetables Can Help Solve World Hunger,” National Geographic, March 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/global-food-waste-statistics

[xlviii] Suzanne Goldenberg, “Half of all US food produce is thrown away, new research suggests,” The Guardian, July 13, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/13/us-food-waste-ugly-fruit-vegetables-perfect

[xlix] Suzanne Goldenberg, “The US throws away as much as half its food produce,” Wired, July 14, 2016, https://www.wired.com/2016/07/us-throws-away-much-half-food-produce

[l] Reynard Loki, “America is a wasteland: The U.S. produces a shocking amount of garbage,” Salon, July 15, 2016, https://www.salon.com/2016/07/15/america_is_a_wasteland_the_u_s_produces_a_shocking_amount_of_garbage_partner

[li] United States 2030 Food Loss and Waste Reduction Goal, EPA (Environmental Protection Agency)

[lii] Elizabeth Royte, “How ‘Ugly’ Fruits and Vegetables Can Help Solve World Hunger,” National Geographic, March 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/global-food-waste-statistics

[liii] Marc Bain, “Consumer culture has found its perfect match in our mobile-first, fast-fashion lifestyles,” Quartz, March 21, 2015, https://qz.com/359040/the-internet-and-cheap-clothes-have-made-us-sport-shoppers

[liv] Jamie Feldman, “The Average Woman Owns Over $500 Worth Of Unworn Clothing, New Survey Reports,” Huffington Post, August 27, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/28/unworn-clothing-survey_n_5048486.html

[lv] Maybelle Morgan, “Throwaway fashion: Women have adopted a ‘wear it once culture,’ binning clothes after only a few wears (so they aren’t pictured in same outfit twice on social media),” Daily Mail, June 9, 2015, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-3116962/Throwaway-fashion-Women-adopted-wear-culture-binning-clothes-wears-aren-t-pictured-outfit-twice-social-media.html

[lvi] Marc Bain, “Consumer culture has found its perfect match in our mobile-first, fast-fashion lifestyles,” Quartz, March 21, 2015, https://qz.com/359040/the-internet-and-cheap-clothes-have-made-us-sport-shoppers

[lvii] Marc Gunther, “Pressure mounts on retailers to reform throwaway clothing culture,” The Guardian, August 10, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/10/pressure-mounts-on-retailers-to-reform-throwaway-clothing-culture

[lviii] Shannon Whitehead, “5 Truths the Fast Fashion Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know,” Huffington Post, August 19, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/shannon-whitehead/5-truths-the-fast-fashion_b_5690575.html

[lix] M. Leanne Lachman and Deborah L. Brett, Generation Y: Shopping and Entertainment in the Digital Age, Urban Land Institute, 2013.

[lx] Shuk-Wah Chung, “Fast fashion is “drowning” the world. We need a Fashion Revolution!” Greenpeace, April 21, 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7539/fast-fashion-is-drowning-the-world-we-need-a-fashion-revolution

[lxi] Sam Williams, “The Environmental Impact Of Clothing,” Huffington Post UK, December 2016, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/sam-williams1/the-environmental-impact-_1_b_13546078.html

[lxii] “Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry,” Environmental Health Perspectives, September 2007, vo. 115, no.9, pp. A449-A454.

[lxiii] Shannon Whitehead, “5 Truths the Fast Fashion Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know,” Huffington Post, August 19, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/shannon-whitehead/5-truths-the-fast-fashion_b_5690575.html

[lxiv] Shuk-Wah Chung, “Fast fashion is “drowning” the world. We need a Fashion Revolution!” Greenpeace, April 21, 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7539/fast-fashion-is-drowning-the-world-we-need-a-fashion-revolution

[lxv] “One garbage truck of textiles wasted every second: report creates vision for change,” Ellen MacArthur Foundation, November 28, 2017, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/news/one-garbage-truck-of-textiles-wasted-every-second-report-creates-vision-for-change

[lxvi] Marc Bain, “Consumer culture has found its perfect match in our mobile-first, fast-fashion lifestyles,” Quartz, March 21, 2015, https://qz.com/359040/the-internet-and-cheap-clothes-have-made-us-sport-shoppers

[lxvii] Marc Gunther, “Pressure mounts on retailers to reform throwaway clothing culture,” The Guardian, August 10, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/10/pressure-mounts-on-retailers-to-reform-throwaway-clothing-culture

[lxviii] Morgan McFall-Johnsen, “The fashion industry emits more carbon than international flights and maritime shipping combined. Here are the biggest ways it impacts the planet,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/fast-fashion-environmental-impact-pollution-emissions-waste-water-2019-10

[lxix] Morgan McFall-Johnsen, “These facts show how unsustainable the fashion industry is,” World Economic Forum, January 21, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/fashion-industry-carbon-unsustainable-environment-pollution

[lxx] Sophie Benson, “It Takes 2,720 Litres Of Water To Make ONE T-Shirt – As Much As You’d Drink In 3 Years,” Refinery 29, March 22, 2018, https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/water-consumption-fashion-industry

[lxxi] Gunther, Marc, “Pressure mounts on retailers to reform throwaway clothing culture,” The Guardian, August 10, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/10/pressure-mounts-on-retailers-to-reform-throwaway-clothing-culture

[lxxii] “Cotton’s Water Footprint: How One T-Shirt Makes A Huge Impact On The Environment,” Huffington Post, January 27, 2013, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/01/27/cottons-water-footprint-world-wildlife-fund_n_2506076.html

[lxxiii] Shuk-Wah Chung, “Fast fashion is “drowning” the world. We need a Fashion Revolution!” Greenpeace, April 21, 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7539/fast-fashion-is-drowning-the-world-we-need-a-fashion-revolution

[lxxiv] Olympic-size swimming pool, Wikipedia.

[lxxv] Sophie Benson, “It Takes 2,720 Litres Of Water To Make ONE T-Shirt – As Much As You’d Drink In 3 Years,” Refinery 29, March 22, 2018, https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/water-consumption-fashion-industry

[lxxvi] “Get the facts about Organic Cotton,” Organic Trade Association, https://ota.com/advocacy/fiber-and-textiles/get-facts-about-organic-cotton

[lxxvii] Shuk-Wah Chung, “Fast fashion is “drowning” the world. We need a Fashion Revolution!” Greenpeace, April 21, 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7539/fast-fashion-is-drowning-the-world-we-need-a-fashion-revolution

[lxxviii] Bain, Marc, “Consumer culture has found its perfect match in our mobile-first, fast-fashion lifestyles,” Quartz, March 21, 2015, https://qz.com/359040/the-internet-and-cheap-clothes-have-made-us-sport-shoppers

[lxxix] Wee, Heesun, “‘Made in USA’ fuels new manufacturing hubs in apparel,” CNBC, September 23, 2013, https://www.cnbc.com/2013/09/23/inside-made-in-the-usa-showcasing-skilled-garment-workers.html

[lxxx] Yallop, Olivia, “Citarum, the most polluted river in the world?” The Telegraph, April 11, 2014, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/environment/10761077/Citarum-the-most-polluted-river-in-the-world.html

[lxxxi] Sweeny, Glynis, “Fast Fashion Is the Second Dirtiest Industry in the World, Next to Big Oil,” EcoWatch, August 17, 2015, https://www.ecowatch.com/fast-fashion-is-the-second-dirtiest-industry-in-the-world-next-to-big–1882083445.html

[lxxxii] “Fast fashion: Rivers turning blue and 500,000 tonnes in landfill,” ABC News Australia, March 28, 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-28/the-price-of-fast-fashion-rivers-turn-blue-tonnes-in-landfill/8389156

[lxxxiii] “One garbage truck of textiles wasted every second: report creates vision for change,” Ellen MacArthur Foundation, November 28, 2017, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/news/one-garbage-truck-of-textiles-wasted-every-second-report-creates-vision-for-change

[lxxxiv] Sweeny, Glynis, “Fast Fashion Is the Second Dirtiest Industry in the World, Next to Big Oil,” EcoWatch, August 17, 2015, https://www.ecowatch.com/fast-fashion-is-the-second-dirtiest-industry-in-the-world-next-to-big–1882083445.html

[lxxxv] Kirchain, Randolph, et al., “Sustainable Apparel Materials,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 22, 2015, p. 17.

[lxxxvi] Williams, Sam, “The Environmental Impact Of Clothing,” Huffington Post UK, December 2016, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/sam-williams1/the-environmental-impact-_1_b_13546078.html

[lxxxvii] Parry, Simon, “The true cost of your cheap clothes: slave wages for Bangladesh factory workers,” Post Magazine, June 11, 2016, http://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1970431/true-cost-your-cheap-clothes-slave-wages-bangladesh-factory

[lxxxviii] Whitehead, Shannon, “5 Truths the Fast Fashion Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know,” Huffington Post, August 19, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/shannon-whitehead/5-truths-the-fast-fashion_b_5690575.html

[lxxxix] “Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry,” Environmental Health Perspectives, September 2007, vo. 115, no.9, pp. A449-A454.

[xc] Parry, Simon, “The true cost of your cheap clothes: slave wages for Bangladesh factory workers,” Post Magazine, June 11, 2016, http://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1970431/true-cost-your-cheap-clothes-slave-wages-bangladesh-factory

[xci] Winn, Patrick, “The slave labor behind your favorite clothing brands: Gap, H&M and more exposed,” Salon, March 22, 2015, https://www.salon.com/2015/03/22/the_slave_labor_behind_your_favorite_clothing_brands_gap_hm_and_more_exposed_partner

[xcii] Quinn, Shannon, “10 Truly Troubling Facts About The Clothing Industry,” List Verse, March 17, 2017, https://listverse.com/2017/03/17/10-truly-troubling-facts-about-the-clothing-industry

[xciii] Apple iPhone sales worldwide 2007-2017, Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/276306/global-apple-iphone-sales-since-fiscal-year-2007

[xciv] Number of smartphones sold to end users worldwide from 2007 to 2017, Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/263437/global-smartphone-sales-to-end-users-since-2007

[xcv] Juli Clover, “Thousands of Customers Waiting in Line at Apple Retail Stores for iPhone XS, XS Max and Apple Watch Series 4 as Global Launch Continues,” MacRumors, September 20, 2018, https://www.macrumors.com/2018/09/20/iphone-xs-apple-watch-launch-day-lines

[xcvi] S. O’Dea, “Number of smartphone users from 2016 to 2021,” Statista, August 20, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide

[xcvii] Syed Faraz Ahmed, “The Global Cost of Electronic Waste,” The Atlantic, September 29, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/09/the-global-cost-of-electronic-waste/502019

[xcviii] Kyree Leary, “The World’s E-Waste Is Piling Up at an Alarming Rate, Says New Report,” Science Alert, December 13, 2017, https://www.sciencealert.com/global-electronic-waste-growth-report-2017-significant-increase

[xcix] Luckyson Zavazava, “The world generated 62 million tonnes of electronic waste in just one year and recycled way too little, UN agencies warn,” Fortune, April 8, 2025, https://fortune.com/2024/04/08/world-generated-62-million-tonnes-electronic-waste-year-un-agencies-warn-tech-environment

[c] “Electronic waste facts,” http://www.theworldcounts.com/counters/waste_pollution_facts/electronic_waste_facts

[ci] “World e-waste rises 8 percent by weight in 2 years as incomes rise, prices fall: UN-backed report,” EurekAlert! December 13, 2017, https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-12/tca-wer120817.php

[cii] Leestma, David, “Electronic Waste Study Finds $65 Billion in Raw Materials Discarded in Just One Year,” EcoWatch, December 14, 2017, https://www.ecowatch.com/electronic-waste-united-nations-2517390624.html

[ciii] Wilson, Mark, “Smartphones Are Killing The Planet Faster Than Anyone Expected,” Fast Company, March 27, 2018, https://www.fastcompany.com/90165365/smartphones-are-wrecking-the-planet-faster-than-anyone-expected

[civ] Leestma, David, “Electronic Waste Study Finds $65 Billion in Raw Materials Discarded in Just One Year,” EcoWatch, December 14, 2017, https://www.ecowatch.com/electronic-waste-united-nations-2517390624.html

[cv] Doyle, Alister, “Electronic waste at new high, squandering gold, other metals: study,” Reuters, December 13, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-environment-waste/electronic-waste-at-new-high-squandering-gold-other-metals-study-idUSKBN1E721G

[cvi] Wilson, Mark, “Smartphones Are Killing The Planet Faster Than Anyone Expected,” Fast Company, March 27, 2018, https://www.fastcompany.com/90165365/smartphones-are-wrecking-the-planet-faster-than-anyone-expected

[cvii] “Responsible Mining: The Value of Cobalt Production Outside of the DRC,” December 3, 2018, Investing News, https://investingnews.com/innspired/cobalt-production-outside-dr-congo-ethical-mining-battery-metals

[cviii] “Is my phone powered by child labour?” Amnesty International, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2016/06/drc-cobalt-child-labour

[cix] Annie Kelly, “Apple and Google named in US lawsuit over Congolese child cobalt mining deaths,” The Guardian, December 16, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/dec/16/apple-and-google-named-in-us-lawsuit-over-congolese-child-cobalt-mining-deaths

[cx] Howard, Emma, “Photocopiers, fridges and flat screen TVs: how second-hand cars are being used to smuggle toxic e-waste,” Unearthed, April 19, 2018, https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2018/04/19/photocopiers-fridges-and-flatscreen-tvs-how-second-hand-cars-are-being-used-to-smuggle-toxic-e-waste

[cxi] Vidal, John, “Toxic E-Waste Dumped in Poor Nations, Says United Nations,” United Nations University, December 16, 2013, https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/toxic-e-waste-dumped-in-poor-nations-says-united-nations

[cxii] Watson, Ivan, “China: The electronic wastebasket of the world,” CNN, May 30, 2013, https://www.cnn.com/2013/05/30/world/asia/china-electronic-waste-e-waste/index.html

[cxiii] “Guiyu: An E-Waste Nightmare,” Greenpeace, http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/campaigns/toxics/problems/e-waste/guiyu

[cxiv] Watson, Ivan, “China: The electronic wastebasket of the world,” CNN, May 30, 2013, https://www.cnn.com/2013/05/30/world/asia/china-electronic-waste-e-waste/index.html

[cxv] “Guiyu: An E-Waste Nightmare,” Greenpeace, http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/campaigns/toxics/problems/e-waste/guiyu

[cxvi] Jayapradha Annamalai, “Occupational health hazards related to informal recycling of E-waste in India: An overview,” Indian Journal of Environmental Medicine, 2015, pp. 61-65, doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.157013

[cxvii] Pearce, Fred, “How 16 ships create as much pollution as all the cars in the world,” Daily Mail, November 21, 2009, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1229857/How-16-ships-create-pollution-cars-world.html

[cxviii] “New NRDC Report: China’s Ports Play Major Role in Country’s Air Pollution Problems,” Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), October 28, 2014, https://www.nrdc.org/media/2014/141028

[cxix] Mikhail Sofiev, “Cleaner fuels for ships provide public health benefits with climate tradeoffs,” Nature Communications, February 6, 2019, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02774-9