Democracy Is Dead! Long Live Democracy

by Iain Davis Apr 8, 2022

The word “democracy” (demokratia) derives from “demos” (people) and “kratos” (power). Literally translated it means “people power.” It is the the best model of governance ever devised. So it is a shame that no one alive on Earth lives in a democracy.

Sadly, most people don’t know what democracy is. As a result, they can be deceived into believing that so-called “representative democracy” is democracy. The electorate are told that representative democracy enables them to exercise “democratic oversight” and that this has something to do with democracy. What a deception—and perhaps a deliberate one.

Not only is representative democracy anti-democratic, its precepts are ignored by governments anyway. Indeed, there is no democracy to be found in any nation. Governments, based upon the idea that representatives are empowered to make laws, are not democracies.

In this article we will discuss the problems inherent in representative democracy and explore what could be the best possible remedy: real democracy.

The Death of Representative Democracy

Democracy has nothing to do with voting to elect representatives. The reason citizens do not need to be represented by politicians is that in a democracy the people make all political decisions themselves.

Many national governments pretend to value democratic principles. They often assert the right to defend democracy in their country or to promote democracy in other countries. None of the governments that make such claims are democratic. Their pretensions often result in war.

As mentioned above, no nation-state currently practices democracy, but many of them foist representative democracy on their citizens. In a democracy, the people are the government. They protect themselves from their own potential errors and excesses through the checks and balances built into the rule of law, which is determined solely by the people.

In a representative democracy, on the other hand, the government claims the authority to “govern” the people and forms an autocratic state for that purpose. So-called representative government “allows” the populace to select their political leaders once every four or five years.

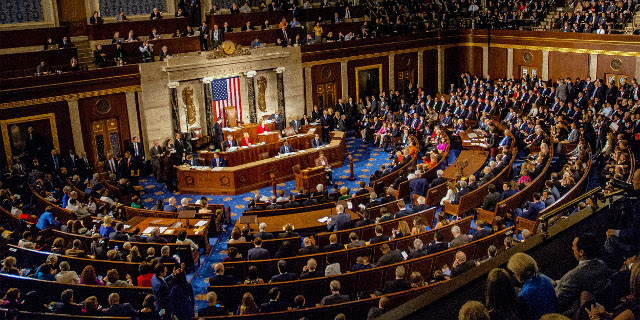

In the years between elections, these “representatives,” few in number, exercise the executive power to rule over everyone else. This form of government is called an oligarchy, and it is the antithesis of a democracy.

The UK Oligarchy

Nonetheless, the people have been “educated” to believe that an oligarchy is a democracy and have become attached to this system. They believe the oligarchy, which they call their “representative government,” honours some foundational principles that are in and of themselves worthy. These principles are often referred to as democratic ideals.

Democratic ideals have been shaped over thousands of years by political leaders, reformists and philosophers. British sociologist T. H. Marshall described democratic ideals in his 1949 essay Citizenship and Social Class. He called them a functioning system of rights. Even though democratic ideals are far from an adequate substitute for democracy, Marshall recognized that they offer a representative democracy’s citizens at least some protection from the whims of the oligarchy whom they’re permitted to elect.

Democratic ideals embrace certain rights—the right to freedom of thought and expression, including speech and peaceful protest, and the right to equal justice and equal opportunity under the law. Apparently these rights are essential and inalienable, for without them representative democracy cannot function.

Oligarchs govern with the aim of protecting and promoting the interests of the establishment. They are put in high political positions to ensure that a nation-state is ruled, from behind the scenes, by the wealthiest individuals and families, the multinational corporations they own, the non-governmental organisations they fund and the banks they control.

The establishment achieve their ends by using their wealth to lobby and corrupt politicians, political parties and the political processes that collectively constitute so-called government. They also form partnerships with this thing called “government.” Through government, public-private partnerships afford members of the establishment direct access to executive power while denying it to everyone else.

Although a representative democracy has supposedly even-handed judges and justices, their decisions often do not reflect good judgement or actual justice for the common man or woman. True, not all judges are corrupt, but a defendant generally needs a lot of money to win a case—proof that the primary purpose of the judicial system in a representative democracy is to protect the authority of the establishment.

Often the people are the victims of court rulings. Jury trials are permitted to a limited extent, but the judge controls and interferes in the process by “instructing” the jurors. Members of the establishment can “appoint” the right judge to the right case and use the courts to persecute citizens, thus warning others not to threaten their authority or interests.

Although a representative democracy has lawmakers, its “rule of law” does not apply to all equally. “Lex iniusta non est lex” (an unjust law is not a law) is supposedly a foundational principle of all of these “legal systems.” Therefore, the alleged rule of law operated by governments cannot be considered to be any law at all.

While some protests are allowed, even encouraged, by representative governments, other protests are not only considered unacceptable but are even attacked by the establishment’s media and suppressed by their “partners” in government. Moreover, representative governments use the venal courts to unlawfully imprison protestors. Procured politicians have also been known to make up powers in order to unlawfully seize protestors’ assets.

Representative governments couldn’t care less about freedom of speech. If a media outlet doesn’t report the authorised news, it is banned or censored in some other way, including having its broadcast license removed. Representative governments routinely work with their establishment partners to actively suppress free speech.

The UK Parliament notes that, for its system of representative democracy to exist, certain liberties have to be maintained:

Freedom of association and freedom of expression are fiercely protected rights. We rightly expect people to be able to say things which challenge or even shock, and to be able to organise, campaign and lobby. Democracy [read: representative democracy] would not function without these rights.

Such language presents advocates of representative democracies with a quandary, because the very oligarchs they have elected and are defending don’t actually respect any of these liberties or alleged rights. Thus, absent any attempt to maintain democratic ideals, representative democracy is, by its own definition, an impossibility.

We need a solution, and democracy offers one.

Inalienable Rights vs Human Rights

Democracy is based upon inalienable rights, not on the political construct of “human rights” which representative democracies claim to bestow upon their citizens. Inalienable rights are “qualified” by nothing other than Natural Law. They are not granted by government.

Inalienable rights are self-limiting, since they require every human being to observe, honour and protect—and never infringe—the inalienable rights of all other human beings. They precede genuine democracy instead of arising from it. Governance exists only by virtue of the people exercising their inalienable rights.

The UK oligarchy itself explains why the aberration of representative democracy doesn’t remotely resemble democracy:

Conversely, democracy [read: representative democracy], along with the rule of law, itself is a precondition for functioning human rights. Few rights are absolute; many are limited or qualified. Sometimes a given context will require different rights to be balanced against one another.

This description is an inversion of the true nature of rights. Inalienable rights are shared equally by all, without exception. No one can add rights or have more rights than another, neither can anyone subtract rights or have fewer rights than another.

No human being has the prerogative to define or to “qualify” the rights of another human being, even if they claim that their so-called “law” allows it. Defining and limiting rights is not a function of democratic governance. It is merely an unjustified claim of right made by authoritarian representative governments. In reality, additional rights do not exist. The belief that they do is a monstrous deceit.

By claiming the non-existent right to create or limit “functioning human rights,” representative oligarchies assume the authority to permit or deny said “rights.” One could say, then, that human rights are not rights but rather government permits.

Representative democracies like the UK parliament assert that they are “sovereign.” They want their constituents to believe that they possess yet another additional—albeit impossible—right to be the supreme legal authority. This is an anti-democratic power grab based upon yet another lie. No, the institutions of government are not sovereign in a democracy; the people are sovereign.

We don’t have to put up with the tyranny of representative democracies or the governments that operate them. There is a better political system called democracy. Let’s explore the latter in more depth.

What Is Democracy?

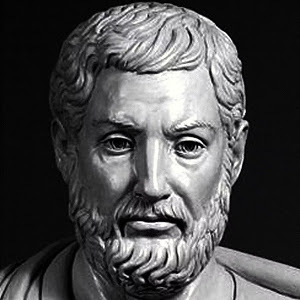

If Solon (c. 630–560 BCE) can be credited with creating the first republic then it is he who can be seen as the father of so-called representative democracy. Solon’s reforms enabled the people to influence their leaders and codified the system of law. However, this was not “democracy.”

Democracy is a political system first and formally established in ancient Greece by Cleisthenes (c. 570–500 BCE). Following the overthrow of the last tyrant of Athens (Hippias) in c. 508 BCE, Cleisthenes led the political and legal reforms that created the Hellenic Athenian Constitution.

Cleisthenes introduced “sortition,” which was the random selection of citizens whose names were drawn by lot. Under his reforms, the Boule proposed legislation (statute law), and the Ecclesia (assembly) would then debate the proposed laws and vote on their implementation. The citizen members of the Boule and the Ecclesia were selected by sortition.

Once their work was done, the Boule and the Ecclesia were disbanded. The people would return to their everyday lives. The next time the Boule and the Ecclesia were needed, sortition would again be used and a different group of people selected.

Sortition was also used to form the juries, whose citizen members sat in the Dikasteria (courts). The jury in the Dikasteria represented the highest law in the land. It could overturn the enactments of the Ecclesia. This political system enabled the people to create legislation (statute law) as well as law derived from precedent (case law).

Ancient Greece wasn’t an egalitarian society in the modern sense. For instance, full citizenship was restricted to non-slave male Athenian landowners. These citizens, selected through sortition, regularly attended the Ecclesia (assembly) on the mount at Phynx. This marketplace of ideas, and other civil activities, was called the Agora.

Proposed statute law (bills) would be presented to the Ecclesia by the Boule. The gathered assembly (Ecclesia) would then vote to either pass or reject proposed bills or suggest amendments. If an amendment were suggested, the bill would be passed back to the Boule for further deliberation.

Crucially, Cleisthenes empowered the Dikasteria (the law courts) to overrule (annul) any law that was found in a trial by jury to be unjust. There were no judges. Magistrates were merely administrators for the court. If the defendant was found guilty, both the judgement (ruling) and the nature of the punishment (sentence) were decided by the citizen jurors.

If the full application of the law (including legislation) did not serve justice, the jury could annul it. The defendant may have technically contravened the law but could still be found not guilty if the jury believed the defendant had acted honourably, without any intent to cause harm or loss (mens rea).

In such a circumstance, it was the law, not the accused, that would be found at fault. Any faulty legislation would be wiped from the statute scrolls, and the Boule would have to amend or abolish the law in light of the Dikasteria’s ruling.

Aristotle would later describe the Athenian Constitution. Unfortunately, when the partial record of Aristotle’s writings was discovered in 1870, his explanation of many of Cleisthenes’ most crucial reforms was missing.

Justice James Wilson, one of the Founding Fathers of the US Constitution, noted the true purpose of the Athenian Constitution:

In Athens the citizens were all equally admitted to vote in the public assembly, and in the courts of justice, whether civil or criminal. [. . .] It [the jury] was favourable to liberty because it could not be influenced by intrigues. In every particular cause the jurors were chosen and sworn anew [. . .] No one might mix with them, or corrupt them, or influence their decisions. [. . .] They were an important body of men, vested with great powers, patrons of liberty, enemies to tyranny.

Wilson added an account of how this system empowered the citizenry. Each citizen, he wrote, had an equal share of political power, for each was vested with . . .

[. . .] Judicial authority[,] as Jurors in Trial by Jury[,] in which laws and measures passed by legislatorial majorities in the assembly could be judged, overruled and annulled whenever this was deemed by the Jurors necessary to serve justice, liberty, and the interests of the people. [. . .] The Jury must do their duty and their whole duty: they must decide the law as well as the fact.

Cleisthenes created a system of government in which the rule of law was created by a sortition of the people. A separate sortition of citizens would then apply the law through the mechanism of trial by jury.

The randomly selected jury of the people was the supreme law of the land. The people were sovereign. This political system, governance by trial by jury, was called demokratia (democracy).

Who do they really represent?

The Implications of A Modern Democracy

As democracy ensures that a governance is conducted by the citizenry, it naturally serves the will of all citizens. Through the system of sortition, citizens chosen at random are briefly given some legislative authority. Then they make way for the next round of sortition. All new legislation is tested in trials by jury. If found wanting, any law can be annulled by a sortition of the people.

As a result, no government has authority over the people. There is no institution with the ability to rule unjustly. Governance is merely the apparatus through which the people administer their affairs and address any issues that may arise. Democracy is the rule of law without rulers.

Citizens who live in a democracy cannot devolve their responsibility for decision-making to someone else. Each citizen is equally responsible for every decision made and for the conduct of society as a whole. Democracy is truly governance of the people, by the people and for the people. It redefines what we mean by the word “government.”

Officers of the law, such as police, magistrates and other administrators, are employed by the people to implement and serve the will of the people. The will of the people is constantly tested and, where circumstances dictate, it adapts.

A democratic society requires the active and constant participation of each and every citizen. Any citizen can at any moment be called up to take his or her place in the Boule, in the Ecclesia or in a jury in the Dikasteria. Citizens are perpetually engaged in the process of governance, both at the national and the local level. All citizens in a democracy have a duty to remain informed and to actively pursue justice.

Consequently, in a democracy the primary objective of education is to develop critical thinking skills. Democracy demands that every adult citizen—today’s citizens include women and are not necessarily landowners—be ready to swear their solemn oath to protect and serve justice. All democratic people must prepare themselves to practice the rule of law.

Because democracy places a duty upon all citizens to be critical thinkers who are able to understand potentially complex issues, examine evidence and act judiciously, propaganda spun by the news media is largely non-existent. There simply isn’t a market for it.

Granted, some citizens in a democracy would still band together to form interest groups and attempt to influence public opinion through propaganda, but the majority of people, schooled in critical thinking, wouldn’t be easily fooled by such deceptions. Sortition greatly reduces the likelihood of propaganda swaying political decisions.

Delivering justice is the primary function of a democratic society. This requires an extensive court system (Dikasterias). The Dikasteria network must be funded in such a way that access to justice is free to all at their point of need. Otherwise, wealth would still dictate access to justice.

Purchased justice is not justice and, as unequal justice cannot exist in a democracy, voluntary arrangements to fund the Dikesteria would need to afford justice to those who lacked the means. Perhaps via some form of means test required to access funds provided through voluntary insurance coverage. Boules and Ecclesia could be funded in the same way.

Democracy decentralises power to the individual. It also necessitates that the institutions of governance (government) are decentralised. No one court (Dikasteria) has primacy. A ruling made in a county or town to annul national legislation carries the same authority as a decision made in the national capital.

In order to operate democracy on a large scale, enabling it to serve a population of many millions, a national Boule, Ecclesia and Dikasteria might be set up to enact primary legislation that shapes the rule of law. The decentralised authority of each local Boule, Ecclesia and Dikasteria would work within this nationwide legislative framework.

Each local Boule and Ecclesia would be free to create local laws that meet local needs, providing that their legislation doesn’t contravene the rule of law. Similarly, these local decisions would be constantly checked and verified by the local Dikasteria. A local decision to annul may affect only local legislation, compelling the local Boule to reconsider a ruling.

In such a system, the overarching rule of law must be just—fair and applied equally to all. Without justice, it would be virtually impossible for the national Boule to function.

Primary legislation must be acceptable to all citizens, no matter their social status. Thus, the legislative framework at the national level would have to be confined to defining principles of law rather than creating specific acts that regulate the entire population. Both the scope and scale of legislation and regulation is miniscule in a democracy compared to a representative democracy or any other form of “government.”

Through the Dikasteria, the question of guilt or innocence is the only determinant of justice. Guilt is found only if the crime violates the principles of Natural Law. Did the accused act with the intention of causing harm or loss? Or was the accused guilty of negligence, thus causing harm or loss? The ruling on a case must not contravene Natural Law. If it does, it will be annulled.

In a democracy all citizens possess immutable, inalienable rights from birth. They are free to exercise those inalienable rights in an honourable way—in harmony with Natural Law. Should they cause harm or loss, thereby infringing another citizen’s inalienable rights, they would be subject to judgement in the Dikasteria.

The use of sortition (the random selection of citizens) and the temporary nature of each citizen’s decision-making power ensure that no political factions can be formed. No alliance, no seeking to advance personal interests, can influence a governance in a democracy.

In any event, there would be no point in trying to do so. Unjust legislation and legal precedent, subsequently judged to have failed to deliver justice, would be annulled through the supreme rule of law, exercised by juries in the Dikasterias across the land.

Politicians and political parties would serve no purpose in a democracy. No one person or party leads a truly democratic government. Democratic decisions cannot be ordered or controlled by any power base.

A democracy doesn’t prohibit citizens from campaigning for change. On the contrary, people are free to petition their local or national Boule. A democratic society is shaped by new ideas and responds to crises as required.

Despite the absence of politicians, people in a democracy might still choose to follow leading campaigners, skilled orators or knowledgeable leaders. What they cannot do is exploit any collective power their association might afford them or succeed in any attempt to coerce or corrupt the legislative process. Sortition precludes the possibility.

Democracy eradicates political power. It would be practically incorruptible.

Democratic Regulation

Secondary legislation, meaning the delegation of political authority to individuals empowered by primary legislation, is an impossibility in a democracy. There is no such thing as democratic executive power.

All are equal under the rule of law, and no individual, group or organisation can be imbued with rights that do not exist. That includes any claimed right to make autocratic regulations.

This does not mean that regulations cannot operate in a democracy. The Ecclesia may, for example, pass regulation on food or drug safety standards. This protects the health of the citizens and is congruent with Natural Law. The democratic rule of law dictates that these regulations must not infringe anyone’s inalienable rights nor cause any harm or loss.

If any regulation unfairly disadvantages some producers and manufacturers, while handing a market advantage to others, it could cause potential harm or loss. Those impacted would be free to bring a case to the Dikasteria, who would then rule on the justice of the regulation.

In any given democracy, it is up to the people to decide how to strike the proper balance. The commercial interests of farmers, retailers and pharmaceutical corporations, for instance, are judged against the need to uphold all peoples’ inalienable right to live healthy lives. Ultimately, this may disadvantage the commercial interests of some, but no one has the inalienable right make a profit by poisoning others.

In a democracy, market regulation can never unjustly cause harm or loss to some simply to protect the interests to others. Any such regulation would swiftly be dispatched in a Dikasteria.

Democracy lends itself well to the operation of a genuinely free market—something that, like democracy, does not currently exist. Free markets produce order without design.

This free market would extend to all aspects of society including the offices of the law. We might envisage security services competing for local policing markets, magistrate companies tendering to provide administration services to the Dikesteria market, and so on.

There is no inalienable right to prosper in a free market. Some will be more successful than others. For example, a policing service that engaged in corruption or racism would soon lose its contract and be replaced by a preferable service provider. Competition between security and other services would increase accountability and improve standards.

Democracy does not stop individuals from accruing wealth, nor does it remove the risk of falling into poverty. However, democracy excludes the possibility that wealth can influence justice or the decisions of a government.

The current imposition of representative oligarchy enables the wealthy and the powerful to influence legislation and regulations to protect their interests and limit the market access of others. In a democracy they would not be able to do this.

Regulations governing markets are minimal in a democracy. No groups can be formed to act as regulators and to potentially build cozy relationships with corporations. Instead, regulations in a democratic society would be made through one process only: the people administering the rule of law.

Democracy allows an authentic free market to blossom and enables innovation to flourish. In such a system, there is no centralised control of industries—healthcare, engineering, technology, agriculture—or of science or of academia. Orthodoxy would become a thing of the past.

Democracy wouldn’t necessarily prevent a corporation from being formed as a sole person in law. However, that is precisely how a corporation would be treated—as an individual entity, with no more or no fewer rights than any other individual human being. Incorporation would not afford a company any additional inalienable rights. Thus, neither money nor connections could skew justice or influence a government. There would be no politician or regulator to connect to, so there would be no one corrupt!

Indeed, corrupt legislation or regulation cannot survive in a democracy. For example, if the Ecclesia passed a law that effectively banned physicians or scientists from researching cancer treatments simply to protect the profits of pharmaceutical corporations, this law would certainly be annulled in a Dikasteria.

Providing equal access to justice is the core objective of a real “democratic government.” Consequently, there is no financial impediment for any individual citizen to bring a case against a corporate “person.” One human person standing before the jury in the Dikasteria would have exactly the same access to justice as any wealthy corporate “person.”

Conclusion?

We are faced with a choice. It is clear that representative democracy does not serve the people. On the contrary, it is an oligarchical system that oppresses the people. Even by the tenets of their own authoritarian doctrine, so-called representative governments no longer practice what they preach, if they ever did. Representative democracy, as the majority of us understand it, is most assuredly dead.

So what are we going to replace it with?

It is obvious what the globalist oligarchs wish to transition us into. They envisage a system of global governance operating as a technocracy, powered by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a Great Reset, Central Bank Digital Currency, and other centralized, digital forms of controlling the masses. Put another way, the oligarchy of today is openly and swiftly moving towards extreme neo-feudalism with the express intention of enslaving humanity.

We must oppose this technocratic nightmare through mass noncompliance. Moreover, we must individually take action every day to move ourselves towards decentralisation and freedom and away from centralised tyranny. But there is little point in opposing one political system or another if we have nothing better to offer in its stead.

If we wish to resist slavery, then, we have to stand for something that defeats slavery. Why not Natural Law and the rule of law through trial by jury?

Why not democracy?

0 Comments