Denying reality: a dangerous delusion

You can tell a lot about the metaphysical health of a society from the philosophical questions it asks itself.

In the case of our own culture, one of the best-known such questions is: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” The answer is quite obviously “yes” and the question is ridiculous on more than one level. For one thing, it is blindly anthropocentric, assuming that the presence of a human being somehow makes a unique difference to the reality of sound.

But even if the “no one” in the question includes the whole range of non-human living creatures that might have heard the hypothetical tree, the whole thing is still inherently absurd. The tree cannot fall silently. It will make a noise as it hits the ground, regardless of whether or not this is witnessed.

This so-called “philosophical puzzle” reflects a deep underlying problem with contemporary thinking, in that it potentially denies the existence of objective reality, suggesting that the crashing sound made by the tree may only become real if it is subjectively experienced by some “one”.

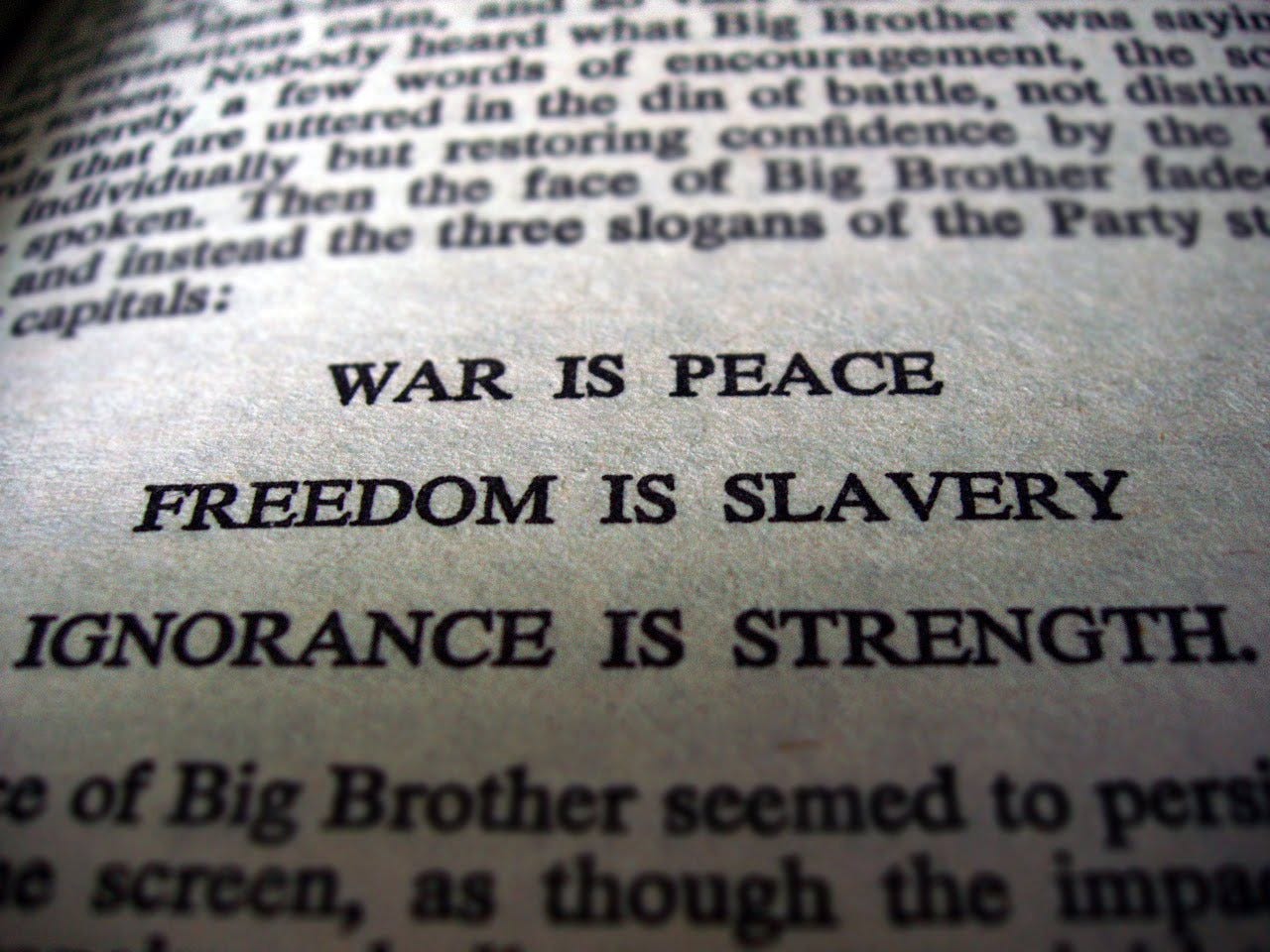

This denial of objective truth is identified as a dangerous delusion by George Orwell in his book 1984. Although presented as a science-fiction warning of a totalitarian society to come, Orwell’s classic novel is, of course, a commentary on mid-20th century realities, exaggerated and projected on to a fictional future. Thus the propaganda machineries of the Ministry of Truth are very much inspired by the author’s personal experiences working for the BBC in London during the Second World War. Likewise with Orwell’s astute observations on a more abstract philosophical level – he is warning us of the way things are heading.

In the novel, Ingsoc’s Big Brother dictatorship has established near-complete control of the population not merely on a physical level, but on a psychological one too – it is able to manipulate the experience of those it dominates, by denying the possibility of any objective reality. “Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense… If both the past and external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable – what then?”1

When O’Brien, the Inner Party stalwart, is torturing the novel’s hero, Winston Smith, he tells him: “You believe that reality is something objective, external, existing in its own right… But I tell you, Winston, that reality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else”.2 Later, he again stresses: “Nothing exists except through human consciousness”.3

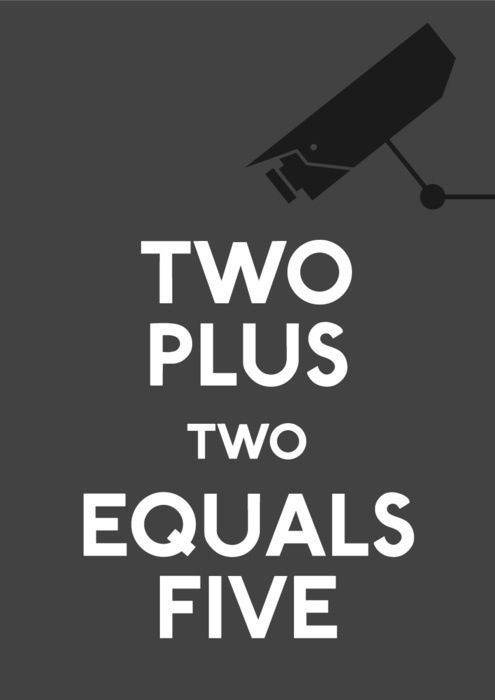

Winston’s struggle to keep a grip on objective reality, to know that two plus two makes four whatever the ideological demands of the Party, is a central theme of Orwell’s novel. Early on in the story the character tells himself: “Truisms are true, hold on to that! The solid world exists, its laws do not change. Stones are hard, water is wet, objects unsupported fall towards the earth’s centre”.4 Orwell has him conclude: “There was truth and there was untruth. And if you clung to the truth even against the whole world, you were not mad”.5

But thanks to all the torture and brainwashing doled out by O’Brien and his comrades, Winston ends up becoming a defeated conformist goodthinker and deciding that this idea of objective truth was an obvious fallacy because “it presupposed that somewhere or other, outside oneself, there was a ‘real’ world where ‘real’ things happened. But how could there be such a world? What knowledge have we of anything, save through our own minds? All happenings are in the mind”.6 Having rid himself of the oldthink notion of objective truth, the way is clear for him to accept that two and two does indeed make five – or any other number that the Party demands.

There seems to be something very modern about this strange delusion that truth is brought into being by someone thinking it, that the sound of a tree falling is purely the result of someone hearing it, that the result of a mathematical process is whatever we want it to be. But I suspect that its origins can be traced back to the latter part of the Middle Ages and the emergence of nominalism.

Nominalism, or the via moderna as it was known for a while, represented a challenge to the certainties of the original oldthink – or via antiqua – which had been inherited from classical Greek philosophy and before that from a catena aurea or golden chain of thought stretching back into remotest antiquity.

This traditional approach, known as realism at the time and today usually termed essentialism, holds that there is an essential reality behind the specifics that surround us in everyday life. This essential reality casts the shadows on the wall of the cave in Plato’s famous philosophical tale. The prisoners mistake the moving shapes for actual reality in the same way that we might mistake temporary physical manifestations of essential reality for the real thing.

The concept is most clearly imagined in terms of numbers. The number “three” exists in abstract form, without the need for the existence of three actual things. The possibility of there being three of something (or seven or nineteen) is always present. The numbers themselves can therefore be described as “existing” – or “subsisting” – on a level more abstract and less transient than that of physical reality.

Likewise, the possibilities of “duration” in time or of “extension” in physical space clearly exist in the same way that mathematical concepts exist, even though they cannot be seen, touched, smelled or heard. The same was held to be true of terms such as “dark” or “light”, “cold” or “hot” and so on – there was an idea that existed in a real but non-physical way, as a kind of necessary potentiality behind actual physical things.

The new thinking challenged the notion that these abstract “universals” actually existed as “things” on some level. Fourteenth century thinker William of Ockham said that all such categories were, instead, concepts formed in the human mind, while fully-fledged nominalists said these categories were just words – hence “nominalism”, from nomen, the Latin for “name”.

The nominalists were not disputing the existence of objective reality as such, just the existence or subsistence of universals, which they regarded as categories which had merely been created in our heads. However, with historical hindsight, this was a significant step towards the human narcissism that was to characterise the centuries to come. We were starting to imagine certain intangible non-human aspects of the world around us as merely the constructs of human minds and language.

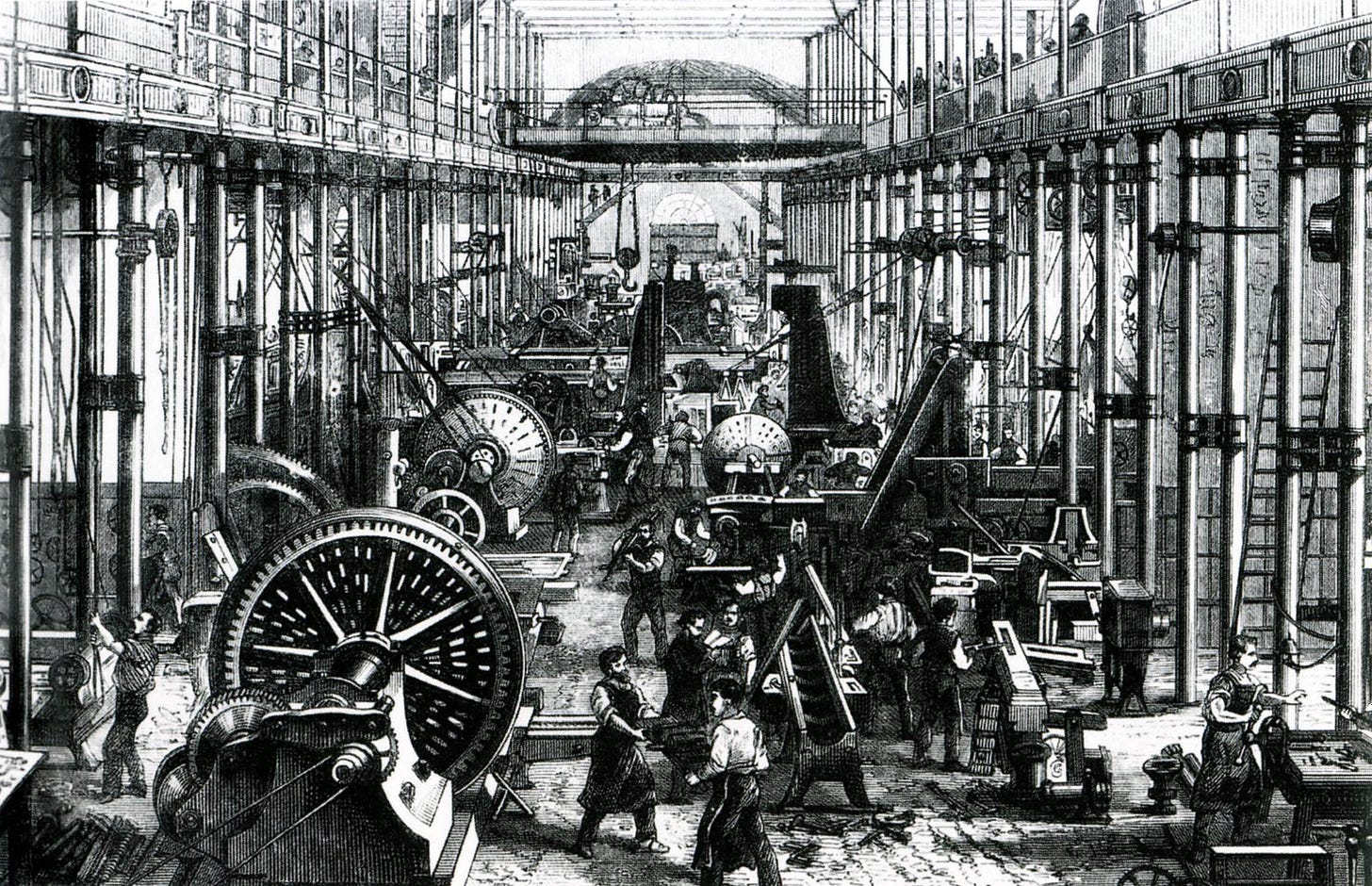

Our thinking has also been industrialised

As humans were increasingly separated from the rest of nature by the industrialisation of society, the process was justified by the new ways of thinking. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) redefined the interconnected organic natural world as a brutal battlefield between selfish individual creatures, while John Locke (1632-1704) effectively denied that humans even formed part of nature, but claimed they were born with no innate qualities at all. This, of course, made them the entirely-malleable products of the specific human society into which they were born.

This industrial-scientific thinking, in the form of positivism, dominated European thought for centuries and paved the way for the massive social changes, termed “progress”, which have created the world we find ourselves in today. If humans were not part of nature, it was simply there to be exploited for our own benefit. If human communities did not exist, but were just collections of individuals, there was no problem in destroying them.

Inevitably, though, there has been some reaction to the rigidity of this scientific-capitalist outlook (which also, unfortunately, infected supposedly oppositional philosophies such as socialism and anarchism7). Some of this reaction took the form of what Michael Löwy describes as “Romantic anti-capitalism”8 and related currents of thought reclaiming the connection to the natural world denied by positivism.

Another angle involved a deep analysis of the relationships and structures within human society, which revealed realities overlooked by over-simplistic economic and social analysis. This very much appealed to anarchists, whose broad critique of contemporary capitalist society had always reached down below the surface of economic life into the murky zone of all those assumptions and formulations which make up the system of domination. Gustav Landauer, for instance, had been pointing out as early as 1910 that “The state is a social relationship; a certain way of people relating to one another. It can be destroyed by creating new social relationships; i.e., by people relating to one another differently”.9

Gustav Landauer

The criticism of mass society pioneered by the Frankfurt School and the Situationists was taken in interesting new directions by Michel Foucault and other postmodern thinkers. They identified hidden power structures embedded in society – within the mental health system, prisons, education, families and in gender definitions, for instance. In many ways this analysis sat well with anarchist thinking, in that it exposed and challenged means of social control that were not obvious on the “political” surface. Saul Newman, in his influential essay The Politics of Postanarchism, claims that postanarchism, which is part of this general trend, has performed “a salvage operation on classical anarchism” and broadened its philosophical horizons.10

But this approach also brought with it certain problems and in many instances served to undermine, rather than underwrite, left-wing criticism of capitalist society. This phenomenon is discussed in some detail by Renaud Garcia in his 2015 book Le désert de la critique.11 Here he offers an invaluable analysis of the effect of the postmodern approach, particularly the intellectual impact of Foucaultian thought on anarchist and left-wing thinking.

Of particular concern is the way that the postanarchists have continued where the post-medieval nominalists left off, in denying the existence of certain notions which were previously considered to be real. Foucault himself even used the label “nominalist” to describe his approach.12

This deconstruction of reality goes well beyond the anarchist insight of denying fake concepts which are used to deceive and dominate – such as “property” or “law” or “nation”. It questions the actual existence of any dominant entity or structure which exploits and dominates us. In fact, the very context in which Foucault describes himself as a “nominalist” is in arguing that it is naive to think you can fight repressive external “power” , since it only exists within inter-personal relationships.13

Michel Foucault

Newman likewise refutes the old-fashioned anarchist notion of there being “a subject whose natural human essence is repressed by power” and claims that “this form of subjectivity is actually an effect of power”. He argues: “This subjectivity has been produced in such a way that it sees itself as having an essence that is repressed – so that its liberation is actually concomitant with its continued domination”.14 This comes dangerously close to a declaration that “Liberation is Domination” – a slogan worthy of being placed alongside “War is Peace” and “Slavery is Freedom” in the lexicon of Orwellian goodthink!

On a metaphysical level, postanarchists, like all postmodernists, deny that there is any essence behind anything in the world. Nothing in the human mind is innate and there is no such thing as human nature. The very idea of “humanity” as a universal concept is rejected. In his essay, Newman specifically opposes the notion of “a universal human essence with rational and moral characteristics”15 which, as he notes, forms the basis of Kropotkin and Bakunin’s anarchism. Indeed, not only do the postmodernists insist that universals do not exist, but they claim that the very idea of universals is part of the domination that we have to resist. Anything that smacks of “essentialism” is not only questionable, but dangerous.

It is at this point that the approach of the postanarchists starts to combine a version of nominalism with the manipulative dogmatism of Orwell’s fictional Ingsoc totalitarians. The meaning of terms is contaminated in order to make their continued usage unacceptable in goodthinking circles. Thus, for many contemporary left-wingers influenced by postmodernism, “essentialism” no longer indicates the metaphysical position held by Plotinus, Plato and generations of thinkers before them, but something more akin to a rigid social conservatism. For them, an “essentialist” is a reactionary who believes that each of us is born into a certain slot in society determined by our heredity, ethnicity, sex and so on.

The difference is purely a construct

“Human nature” is likewise seen by Foucaultians as nothing but a construct, which is used to justify the narrow limits imposed on individual potential by a system of domination. This idea of “human nature” might dictate, for instance, that people should live in family units, pair off in monogamous heterosexual couples, restrict their own sense of identity to those deemed “natural” by that particular society.

From this postmodern point of view, the possibility of anything being “innate” to human beings is regarded as absurd, threatening and close to racism – it denies us the absolute freedom of constructing our own selves. The idea of something being “universal” is seen as an imposition from above, an attempt to eradicate diversity in the name of some all-embracing constructed standard. Even the concept of “humanity” itself is seen as being suspect by this school of thought and regarded as a plurality-denying device with which to bring people under a theoretical umbrella of domination.

However, these postanarchist definitions of essentialism, human nature or universality are nothing but caricatures, based on the narrowest and most reactionary usage of each term and imposing the worst-possible interpretation of the intent behind them (isn’t it possible that someone who expands his or her personal vision to include the whole of humankind might be motivated by an open-hearted desire for inclusion rather than a manipulative urge for repression?).

They are straw man definitions – deliberately inadequate representations of a certain point of view set up by an opponent for the sole purpose of being easily knocked down. As a result, the real philosophies behind these fake versions can no longer easily be distinguished and once the terms in question have successfully been contaminated, it becomes impossible to use them without immediately appearing to be expressing the completely unacceptable views with which they are now automatically associated.

Orwell describes this linguistic blocking process in his novel: “All mans are equal was a possible Newspeak sentence, but only in the same sense in which All men are redhaired is a possible Oldspeak sentence. It did not contain a grammatical error, but it expressed a palpable untruth, i.e., that all men are of equal size, weight or strength. The concept of political equality no longer existed, and this secondary meaning had accordingly been purged out of the word equal”.16

Contemporary “anti-naturalists” (to use Garcia’s term) in fact pull off the impressive ideological gymnastic feat of endorsing right-wing definitions of words in order to dismiss as right-wing all those trying to use the words in different ways.

Thus left-wing anarchist definitions of human nature (as intrinsically co-operative rather than competitive, as something potentially broad and diverse that has been stifled by the repressive limits of contemporary society) are ignored and replaced by narrow right-wing neo-Darwinist notions. Any use of the term “human nature” is thereafter interpreted as an endorsement of the right-wing version adopted by the postmodernists themselves. It becomes impossible to use “human nature” in a left-wing anarchist sense. You would think Kropotkin had never existed!

All of this manipulation is built on a misunderstanding of the relationship between human language and actual reality. It is simply not true to say that “nature”, for instance, is only a word. It is a word, and thus capable of containing all sorts of meaning dictated by the cultural context in which it is used. But, like all words, it is also used to designate something beyond the word itself. Just because “nature” is a word does not mean it is not also a real thing. Sometimes, of course, words do not relate to something real at all. But the existence of a word certainly does not preclude the existence of a real thing, even though when a word describes something that is not empirically observable, the relationship between the word and the thing it designates becomes more difficult to grasp.

Window – “just a word” or a real thing as well?

If I use the word “window”, I am still using a mere word. The concept of “window” is large enough to include a variety of different kinds of window and one person’s mental picture of what that window might look like will no doubt vary from another’s. However, nobody would suggest that because “window” is only a word, there is no such thing as a window in reality. In fact we are talking about two different phenomena here, operating on two distinct levels. On the level of language there is the word “window” and on the level of reality there is the actual thing that is a window, in all its various specific manifestations.

Supposing for some reason a society had misused the word “window” in some way – perhaps, for instance, by applying it solely to stained-glass windows of the kind used in churches. The word “window” as used by that society would therefore become suspect and loaded with an artificial and ecclesiastical restriction to its meaning. In the same way we might say that the word “nature” as used by 19th century right-wing neo-Darwinists also became suspect. But the suspect definition of the word “window” in that imaginary society would not mean that actual windows, as we know them, would have suddenly ceased to exist! There is no direct causal relationship here between the use of a specific word and the nature of objective reality.

You can distort the meaning of the word “window” all you like, redefine it to mean “cabbage” if you choose, but the window next to me as I write these words will remain the same. Likewise, nature remains nature, regardless of how the mere word “nature” might be manipulated or misused. Nature is not in any way dependent on the human word “nature” for its existence or essence.

Postmodernists have fallen into the nominalist trap of believing that the reality of human language and thought – the subjective truth of human beings – is more real than actual objective truth. They mistake word for reality, shadow for object. This is not a question of whether or not we can adequately understand abstract realities, like “nature” or “universals”. From our limited human perspective that may not be possible. But it is a mistake to imagine that something we cannot observe or define, or which we usually designate with a word that is loaded with our own limited subjective social assumptions, consequently does not exist at all.

This mistake is like a small child playing “hide and seek” for the first time, who imagines that if he closes his eyes and thus cannot see his playmates, his playmates will not be able to see him either. This child has not grasped that his own subjective experience of reality is not the same as objective reality. This mistake is also like a contemporary philosopher who ponders long and hard over whether a tree crashing loudly to the earth in a forest can really be said to have made any sound, if this has not been subjectively experienced by a human being like him.

The political implications of this metaphysical mess are worrying. We have now reached the sorry point where it seems that any mention of the essence behind something, or of anything remotely universal, sets the ideological alarm bells ringing.

We are apparently expected to censor ourselves in advance by never uttering such terms and by deploying what Orwell terms crimestop – “the faculty of stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought”.17 This even now seems to apply to the classic anarchist argument, as put forward by Kropotkin, that humanity (stop!) is innately (stop!!) disposed to co-operation and mutual aid and thus could naturally (stop!!!) live perfectly well without state management.

In 1984, one of the Party members developing Newspeak tells Winston Smith: “You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words – scores of them, hundreds of them, every day”.18 He explains: “Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thought-crime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it… By 2050 – earlier, probably – all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed”.19

In destroying the full metaphysical meaning of words like “essence”, “nature” or “universal” by means of their straw man constructs, the conformists of contemporary goodthink are destroying our connection to reality. Because they ideologically object to everything beyond subjective individual experience, they are destroying, in particular, our connection to the reality that we human beings are more than individuals.

They are destroying our understanding that our individual freedom and well-being are in fact dependent on a collective level of existence as part of a community, as part of a species and as part of nature as a whole. They are thus destroying our capacity to see what has been stolen from us by the alienation and separation of the industrial capitalist system and what it is that we must reclaim. “If one is to rule, and to continue ruling,” declares Orwell’s Emmanuel Goldstein, “one must be able to dislocate the sense of reality”.20

A philosophically dislocated anti-capitalist movement that has lost all sense of what it is fighting against and what it is fighting for will never be able to persuade the rest of the population of its arguments and thus will never represent any kind of threat to the dominant system.

Hopelessly naive, according to contemporary sophisticates

Another part of this ideological dislocation is the undermining of our belief that the world of which we dream could one day come about. The abstract (and thus physically “unreal”) possibility of a future anarchist society – without domination, exploitation and alienation – is something that has always sustained us in our struggle.

Another world is possible, we like to remind ourselves. Convincing rebels that this possibility does not and cannot exist, that their resistance is futile, is an obvious counter-revolutionary strategy. O’Brien tells Smith in 1984: “If you have ever cherished any dreams of violent insurrection, you must abandon them. There is no way in which the Party can be overthrown. The rule of the Party is forever. Make that the starting point of your thoughts”.21

A similar message is being delivered by the postmodernists and spreading as a self-destructive meme within what should be the anti-capitalist movement. This tells us that the system we oppose does not even exist as an external objective reality but that, in Newman’s words, we should instead look to “our complicity in relations and practices of power that often dominate us”.22 The reality of our repression and exploitation by a solidly-existing ruling elite is not only questioned in this way, but turned into an accusation against would-be rebels.

The convoluted reasoning, cited earlier, which leads Newman to conclude that “the universal human subject that is central to anarchism is itself a mechanism of domination”23 is not one that inspires revolutionary engagement. What would be the point, if we are dominated primarily by our own mistaken belief that we are being dominated? In any case, for Newman, history is just “a series of haphazard accidents and contingencies, without origin or purpose” and “we have to assume that there is no essentialist outside to power — no firm ontological or epistemological ground for resistance, beyond the order of power”.24

This is your reality, so get used to it

For postanarchists, there is no objective reality beyond the fixtures and fittings of the society we know today – no universal human spirit, no innate desire for freedom, no essential belonging to community, species or planet and, therefore, no possibility of ever rediscovering that belonging.

As David Graeber and others have pointed out, there is little that ultimately separates this vision of the world from the dominant neoliberal ideology.25 Both world-views preach a general acceptance of the one and only reality of fragmented industrial-capitalist society and locate freedom within the individual “choices” that can be made inside that “haphazard” world.

All we have to do is to sit back and enjoy the ride into the industrial capitalist future that is the only possible future available to us, give up all hope of revolution, accept the defeatist newthink of the Party’s post-philosophers, reject the idea of objective truth, understand that two and two makes five and learn to love Big Brother.

Subscribe to Nevermore Media

(This is the second essay in my latest book, Nature, Essence and Anarchy, published by Winter Oak Press)

- George Orwell, 1984, (New York: Signet, 1950) p. 80. The original UK title is Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Orwell, p. 249.

- Orwell, p. 265.

- Orwell, p. 81.

- Orwell, p. 217.

- Orwell, p. 278.

- See José Ardillo, Les illusions renouvelables (Paris: L’Échappée, 2015).

- Michael Löwy, Rédemption et utopie: le judaïsme libertaire en Europe centrale, (Paris: Éditions du Sandre, 2009) p. 40.

- Gustav Landauer, Weak Statesmen, Weaker People! in Revolution and Other Writings: A Political Reader, ed. and trans. by Gabriel Kuhn, (Oakland: PM Press, 2010) p. 214.

- Saul Newman, The Politics of Postanarchism, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/saul-newman-the-politics-of-postanarchism

- Renaud Garcia, Le désert de la critique: Déconstruction et politique (Paris: L’Échappée, 2015).

- Garcia, p. 117.

- Ibid.

- Newman.

- Ibid.

- Orwell, p. 310.

- Orwell, p. 212.

- Orwell, pp. 50-51.

- Orwell, pp. 52-3.

- Orwell, p. 215.

- Orwell, pp. 261-62.

- Newman.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David Graeber, Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our Own Dreams (New York: Palgrave, 2001).

0 Comments