Empire of Hypocrisy

by Paul Cudenec | May 15, 2022

1. The nice imperialists

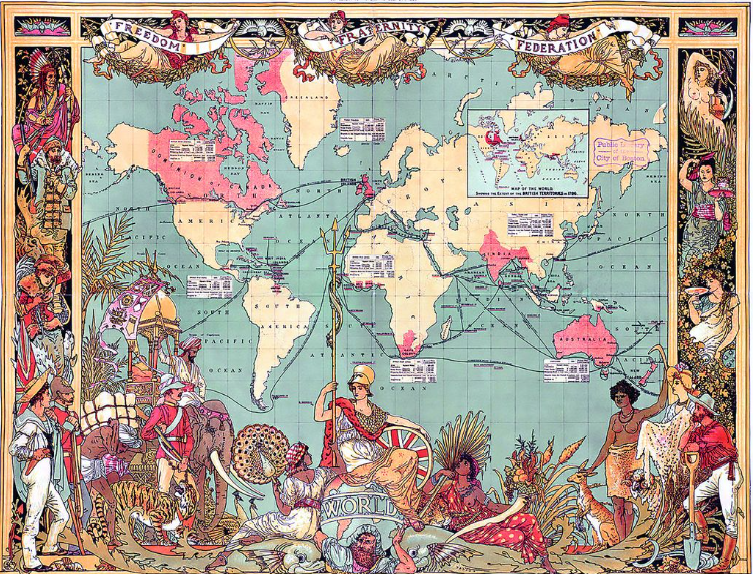

In the middle of the 19th century, the British Empire ran into what what would today be termed a “public relations crisis”.

Influential domestic voices were starting to criticise its industrial system and worldwide domination on ethical grounds, not least the art critic John Ruskin

He wrote that all he had found at the heart of what was supposedly a great civilization was “insane religion, degraded art, merciless war, sullen toil, detestable pleasure, and vain or vile hope”. (1)

Lack of public support for the empire at home from the wave of “Little Englander” sentiment also risked affecting the way Britain’s activities were viewed abroad.

As Carroll Quigley writes, its success was partly due to “its ability to present itself to the world as the defender of the freedoms and rights of small nations and of diverse social and religious groups”. (2)

It was therefore decided, by a powerful group based around Cecil Rhodes and Lord Milner, along with aristocrats such as Lord Esher, Lord Rothschild and Lord Balfour, (3) to rethink the form and appearance of Britain’s economic sphere of influence.

Gradually, the Crown’s possessions were encouraged to become supposedly independent nations, though very much remaining under Britain’s wing, and eventually, after the Second World War, The Empire was rebranded The Commonwealth, whose current flag features at the top of this page.

In her foreword to a very useful 2019 collection of the Commonwealth’s declarations, its current secretary-general, Patricia Scotland (pictured), writes: “The 1949 London Declaration marks the opening of a new movement, maintaining the familiar harmony, yet developing it in ways never before attempted – the transformation of an empire into a mutually supporting family of nations and peoples. It was this brief yet visionary declaration which brought into being the Commonwealth we know today”. (4)

Today we are very familiar with the two-faced language of power, which is constantly deployed to hide unpalatable truth from the public.

Whether in the form of corporate greenwashing, warmongering “humanitarian interventions” or censorship disguised as “fact-checking”, this cynical misuse of words has long since surpassed the satire of George Orwell’s mendacious Ministry of Truth.

The phenomenon is global now, but Britain can look back with pride at its leading role in developing this fraudulent double-speak.

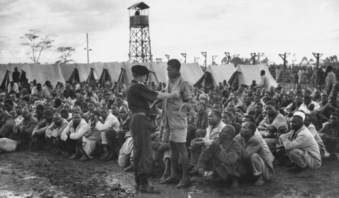

The British Empire’s self-declared commitment to “the protection and advancement of the native races” (5) did not stop it from opening fire on unarmed Gandhi-supporting Indian independence protesters in Amritsar in 1919, killing 379 people, (6) or from using mass murder, torture and concentration camps to crush the anti-imperialist Mau Mau revolt in Kenya between 1948 and 1955.

The self-righteous defender of worldwide freedom acquiesced in the rise of Hitler’s Germany, simultaneously denounced (in public) and tolerated (in private) Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia and did all it could to hinder resistance to Franco’s far-right coup in Spain in 1936, despite its own public’s overwhelming support for the other side.

“Britain’s attitude was so devious that it can hardly be untangled,” (7) writes Quigley about this period. “The motives of the government were clearly not the same as the motives of the people, and in no country has secrecy and anonymity been carried so far or been so well preserved as in Britain”. (8)

Over the 70-plus years of his existence, The Commonwealth has proudly continued this official practice of manipulative and virtue-signalling language.

Back in 1944, the nascent entity declared: “We seek no advantages for ourselves at the cost of others. We desire the welfare and social advance of all nations and that they may help each other to better and broader days”. (9)

“An ethic of non-violence must be at the heart of all efforts to ensure peace and harmony in the world”

In 1971 The Commonwealth absurdly claimed to “oppose all forms of colonial domination” (10) and in 1983 this new cuddly version of the British Empire even had the gall to announce that “an ethic of non-violence must be at the heart of all efforts to ensure peace and harmony in the world”. (11)

All it wanted in 2002 was “a better world for our children”, (12) with secretary-general Scotland confirming in recent years that the aim was purely and simply “to build a more equal, just and peaceful world” (13) and “to achieve practical progress for the good of all”. (14)

In her fanciful framing, The Commonwealth, which embraces 54 countries and 2.5 billion people, is not an empire but “a vibrant geopolitical ecosystem”. (15)

And, according to The Commonwealth’s own charter, it is “a compelling force for good” dedicated to “international understanding and world peace”.

However, the same document also describes the organisation as “an effective network for co-operation and for promoting development” and here we catch a glimpse of the reality behind the rose-tinted verbiage.

Aso Rock

The same is true of a 2003 declaration in which Commonwealth leaders (pictured here) committed themselves to “strengthen development and democracy, through partnership for peace and prosperity”. (16)

Through the use of alliterative pairings, the authors of this text obviously aimed to give the impression that “development and democracy” are but two sides of the same coin, as are “peace and prosperity”.

But this is mere verbal manipulation and the four words would perhaps better be re-arranged as a contrast between the idealistic packaging of “democracy and peace” and the essential contents of “development and prosperity” – terms which, although themselves euphemisms, point us towards the real core Commonwealth agenda.

Needless to say, from The Commonwealth’s point of view, “development” is a good thing and it even claims that there is such a thing as “pro-poor development”. (17)

Likewise, globalisation, which is just the extension of the same process, is not seen as the cause of worldwide misery but as the magic “solution” to the “problem” termed “poverty”.

“The benefits of globalisation must be shared more widely”, insisted a Commonwealth declaration in 2002. (18)

The Commonwealth likes to tell people that they are poor and “underdeveloped” and that they are being unfairly deprived of what it calls “the right to development”. (19)

But this, as the Mexican activist Gustavo Esteva has pointed out, is “a manipulative trick to involve people in struggles for getting what the powerful want to impose on them”. (20)

He adds: “The metaphor of development gave global hegemony to a purely Western genealogy of history, robbing peoples of different cultures of the opportunity to define the forms of their social life”. (21)

In the same way, “sustainable development” is presented as additionally being a “solution” for the environmental degradation inflicted by the original “pro-poor development”.

However, as Esteva observed, “sustainable development has been explicitly conceived as a strategy for sustaining ‘development’, not for supporting the flourishing and enduring of an infinitely diverse natural and social life”. (22)

The German researcher and author Wolfgang Sachs also warned the world about so-called sustainable development back in 1992.

He wrote: “This is nothing less than the repeat of a proven ruse: every time in the last thirty years when the destructive effects of development were recognized, the concept was stretched in such a way as to include both injury and therapy.

“For example, when it became obvious, around 1970, that the pursuit of development actually intensified poverty, the notion of ‘equitable development’ was invented so as to reconcile the irreconcilable: the creation of poverty with the abolition of poverty.

“In the same vein, the Brundtland Report incorporated concern for the environment into the concept of development by erecting ‘sustainable development’ as the conceptual roof for both violating and healing the environment”. (23)

Once again, we are witnessing the old imperial trick of cynically using deceptively positive-sounding terms to mask a negative reality.

As we will discover later, The Commonwealth and its friends are now intent on pushing their holy cow of “development” into chilling new areas.

But first, let’s have a look at the organisation’s political agenda as revealed by its own literature.

2. A global agenda

The Commonwealth makes no secret of the fact that its mission is a globalising one, even referring to a mysterious something called “the world community”. (24)

In this respect it very much doffs its hat to the United Nations.

Already in 1951 it was announcing: “Our support of the United Nations needs no re-affirmation. The Commonwealth and the United Nations are not inconsistent bodies. On the contrary, the existence of the Commonwealth, linked together by ties of friendship, common purpose and common endeavour, is a source of power behind the Charter”. (25)

A 1985 declaration stressed “the need for world order and the central importance of the United Nations system”. (26)

It added that it placed The Commonwealth’s resources “at the service of the United Nations and of all efforts to make it more effective” because “in the future of the United Nations lies the future of humanity”. (27)

Dr Musarrat Maisha Reza writes in The Commonwealth’s 2020 Global Youth Development Report of the critical need to “reach our Agenda 2030 and to deliver national and global goals”. (28)

It is also notable that the version of reality presented by The Commonwealth, along with the language it uses to convey it, is almost indistinguishable from that of another global organisation, namely the World Economic Forum and its subsidiary tentacles like the Global Shapers.

It is also notable that the version of reality presented by The Commonwealth, along with the language it uses to convey it, is almost indistinguishable from that of another global organisation, namely the World Economic Forum and its subsidiary tentacles like the Global Shapers.

This is perhaps none too surprising, given that the WEF’s Great Reset was launched by the future head of The Commonwealth, as we reported in this recent article.

And, of course, some of the most extreme and draconian Covid-facilitated repression since 2020 has been in the Commonwealth nations of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The Commonwealth is fully on message with the whole Great Reset agenda: its youth development report welcomes a Fourth Industrial Revolution which is “blurring the distinction between the digital and physical worlds” (29) and deploys the phrase “build back better” on four separate occasions.

Despite voicing pious concerns about the negative effects of “the pandemic”, it clearly joins the WEF’s Klaus Schwab in regarding Covid as rather good news.

On one level the crisis created a new “problem” for which “solutions” can be sold via the mechanisms associated with “development”.

Mamta Murthi of the World Bank Group, a guest contributor to The Commonwealth’s youth report, is delighted to relate that his organisation is “taking fast, comprehensive action to fight the impacts of the pandemic”. (30)

He continues: “Between April 2020 and June 2021, WBG financing commitments reached over $150 billion, including an unprecedented $12 billion response to improve social protection and create employment opportunities in 56 developing countries, including 15 countries facing fragility and conflict”.

He continues: “Between April 2020 and June 2021, WBG financing commitments reached over $150 billion, including an unprecedented $12 billion response to improve social protection and create employment opportunities in 56 developing countries, including 15 countries facing fragility and conflict”.

Murthi also sees a positive in the fact that “the pandemic has intensified the pace of change in the labor market and the demand for new skills”. (31)

The report’s Executive Summary likewise enthuses that Covid “has created new opportunities for online work”. (32)

“The pandemic has fast-tracked our reliance on digital communication, business and retail technologies, and centred the need for pervasive digitisation”, adds another article. (33)

This aspect, in fact, seems to be the chief cause for Covid celebration at Marlborough House, The Commonwealth’s headquarters on London’s swanky Pall Mall.

They are in awe of “the scope, speed and scale” of changes which will create for young people “an entirely different world to that experienced by previous generations” and they stress that “at the core of this change is the digitalisation of the economic system”. (34)

Being what it is, The Commonwealth has always felt the need to dress up this digital agenda in hypocritical fakespeak.

Thus a 2002 declaration spoke of the need to “bridge the information and communications technology gap between rich and poor”, (35) while the 2018 Commonwealth Cyber Declaration poured on the saccharine wokeness with its commitment to “take steps towards expanding digital access and digital inclusion for all communities without discrimination and regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age, geographic location or language”. (36)

Its list of Commonwealth Youth COVID-19 Heroes, “who are positive lights in the pandemic” (37) reveals the same theme.

One young woman in India is praised for having set up “a virtual learning programme in 6 community libraries” and for having worked with doctors “to create informative posters in regional languages to tackle health misinformation” and a “hero” in Pakistan “partnered with private institutions to provide telemedicine services to the public”.

One young woman in India is praised for having set up “a virtual learning programme in 6 community libraries” and for having worked with doctors “to create informative posters in regional languages to tackle health misinformation” and a “hero” in Pakistan “partnered with private institutions to provide telemedicine services to the public”.

A young New Zealander helped her community by launching “GirlBoss Edge – a virtual career accelerator”, a Nigerian man “translated COVID-19 health messages from WHO into more than 100 languages, reaching over 1.5 million people” and “launched an Artificial Intelligence-driven app and chatbot”, while a Commonwealth hero in Jamaica “co-launched an online app helping 100,000 people find their nearest COVID-19 testing sites”.

When The Commonwealth’s youth report argues that “greater investment in skilling for the digital economy will be required” (38) for the sake of “disadvantaged youth’s career prospects”, (39) it is hard not to think of the original British Empire’s avowed mission to “civilize the natives”.

And, lo and behold, The Commonwealth has chosen to recycle that very term for the 2020s, stating: “The need for young people to become digital natives has never been more important”. (40)

It even promotes a “digital natives indicator, which measures young people’s skills and online engagement”. (41)

The report looks at the project of “redesigning work with a digital future in mind” (42) and contributors Swartz and Krish Chetty, from South Africa, even provide a list of suitable jobs for young people in the post-Covid New Normal.

They could work in “3-D printed designs”, “Recycling through smart tagging”, “Smart farming through Internet of Things (IoT) applications”, “Online retail”, “IoT applications linked to construction projects”, “FinTech applications” (finance), “X-tech” (new innovations) or as a “solar cell manufacturer”. (43)

Once again, we find The Commonwealth’s aims perfectly aligned with those of the global banking and “development” mafia

The one thing they cannot do, of course, in this “entirely different world to that experienced by previous generations” will be to live a traditional lifestyle close to the land.

This was already being spelled out in a 2003 declaration, made in Nigeria: “It is the strategic goal of the Commonwealth to help their pre-industrial members to transition into skilled working- and middle-class societies, recognising that their domestic policies must be conducive to such transitions”. (44)

And the same message was repeated in 2007, with talk of “the objective of speeding up the transition from rural-based towards skilled, middle class-based, industrialised and diversified societies”. (45)

In traditional societies, women usually have a very close connection to the land. But the 2018 Commonwealth Cyber Declaration prefers “to develop skills in the workforce, particularly for women and girls”. (46)

Once again, we find The Commonwealth’s aims perfectly aligned with those of the global banking and “development” mafia.

The World Bank has admitted in its own words that its favoured policy of rural development is “designed to increase production and raise productivity. It is concerned with the monetization and modernization of society, and with its transition from traditional isolation to integration with the national economy”. (47)

To achieve this “transition”, advocates of a global Fourth Industrial Revolution would have to pull off a massive feat of social engineering similar to that imposed on the people of England during the First Industrial Revolution, when the “lower orders” were thrown off the land of their ancestors by the ruling classes.

The dispossessed masses were herded into the slums and factories of domestic industrial “development” or used to advance the empire’s “development” overseas, whether in the armed forces, the merchant navy or colonial administration and policing.

As C. Douglas Lummis, author of the book Radical Democracy, observed: “To ‘mobilize’ (i.e. to conscript) peoples and cultures into the world economic system would require the same disembedding of economic man, the same uprooting, as occurred in the migrations to the US or in the land enclosure movement in England. Only this time, the scale is awesome”. (48)

There is a definite link between the desire to turn young Africans and Asians into “digital natives” and the current global “conservation” agenda aimed at “protecting nature” by depopulating vast swathes of the world.

This insidious project, known variously as The New Deal for Nature, Nature Positive, Global Goal for Nature or 30×30, is backed by the world’s most powerful corporations and financial institutions, as well as by the WEF, which teamed up with the UN in 2019 to push its Sustainable Development Goals or Global Goals.

The charge for the “deal”, an imperialist land grab from the most self-sufficient peoples on the planet, is being led by the human rights violating WWF, which just happens to be an official Commonwealth partner.

3. Human capital

From the heartless perspective of the global development machine, “human beings are perceived as simply one of the many resources required by economy for its own needs” writes Majid Rahnema, a one-time employee of the United Nations Development Programme who became an important and outspoken critic of their global agenda. (49)

The terms used to describe this callous reality have changed over the decades. In 1991 The Commonwealth was still calling for “the development of human resources”. (50)

But, by then, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) had already published, in 1990, its first Human Development Report (51) and this term was soon taken up by The Commonwealth.

The phrases “human development” and “people-centred economic development” featured in Commonwealth declarations in 1999 (52) and in 2002. (53)

In the 2020s the language has gone a step further. Murthi of the World Bank, where he specialises in “human development”, writes in The Commonwealth’s youth report that “protecting and investing in young people builds human capital”. (54)

In the 2020s the language has gone a step further. Murthi of the World Bank, where he specialises in “human development”, writes in The Commonwealth’s youth report that “protecting and investing in young people builds human capital”. (54)

Secretary general Scotland also mentions “human capital development” in her foreword (55) and the term “human capital” appears no fewer than ten times in the report.

What most attracts these financial blood-suckers is the tender flesh of the “more than 1.2 billion young people between the ages of 15 and 29 years who live in our 54 member countries”. (56)

Licking its metaphorical lips, The Commonwealth declared in 2013: “With over 60 per cent of its population aged under 30, the Commonwealth is well placed to reap a demographic dividend”. (57)

It added: “Investing in young people today is the foundation for a prosperous and equitable tomorrow”. (58)

Prosperous for whom, exactly?

A similar question is raised by the words of The Commonwealth’s 2020 youth report: “Today’s global youth boom represents a much-needed opportunity”. (59)

An opportunity for whom? To do what?

The Commonwealth deploys all the usual verbal camouflage to conceal the answers to such questions, affirming, for instance, in 2018 its “commitment to making trade and investment truly inclusive by encouraging the participation of women and youth in business activities”. (60)

In true gaslighting style, it even pretends that young people are crying out to be exploited: “We also hear young people’s call to be facilitated as drivers of economic development”. (61)

The duplicitous term “youth-led”, giving the false impression that its insidious schemes are arising from below rather than being imposed from above, is rolled out a magnificent 40 times in the youth report.

But the truth behind the hype is clearly stated by two particular contributors to that same publication.

Firstly, there is Chris Morris, manager of the Asian Development Bank’s Youth for Asia initiative, whose participation in the report is, in itself, somewhat revealing.

Firstly, there is Chris Morris, manager of the Asian Development Bank’s Youth for Asia initiative, whose participation in the report is, in itself, somewhat revealing.

He writes that “accelerating progress towards a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific will require mobilizing the potential of its one billion young people”. (62)

Secondly, there is Tijani Christian, chairperson of the Commonwealth Youth Council, who says: “Today, the world has the largest population of youth people [sic] in existence, with the Commonwealth alone having 60 per cent of its population below the age of 30.

“These extremely important assets must be protected and upskilled for countries to truly advance their economic growth and development agendas”. (63)

The real relationship between The Commonwealth and its “family of nations and peoples” here becomes starkly clear.

When the City of London vampires look at men, women and children in Africa, Asia or elsewhere, they don’t see fellow human beings but “assets” with “potential”, “human capital” from which they hope to derive a highly lucrative “demographic dividend”.

4. Impact outcomes

The principal tool with which the global imperialists aim to force future generations into a UN-approved “resilient and sustainable future” (64) is digital data.

This was already being announced in 1991, when The Commonwealth declared its intention “to improve the collection of data – quantitative and qualitative – and the development of methods and statistical indicators, globally and nationally”. (65)

Florence Nakiwala Kiyingi, chair of the Commonwealth Youth Ministerial Task Force, recalls that at the 9th Meeting of Commonwealth Youth Ministers in 2017, they committed to “developing new ideas for financing youth development and improving data for monitoring our progress on pursuing positive outcomes for youth in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”. (66)

Regular Winter Oak readers will have immediately have spotted that we are dealing here with “impact” imperialism, the means by which financial interests hope to make their profiteering domination “sustainable” and “resilient” in the decades to come.

As we have explained elsewhere (see the links here), the aim is not only to privatise social interventions once handled by the state, but to bundle people’s lives into tradable commodities on which financiers can speculate.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals constitute the framework through which this new digital form of slavery is to be legitimised and imposed worldwide.

For this to work, those in charge have to be able to measure the “outcome”, the success or failure of their asset, either of which can be profitable for wily speculators.

Because impact investments involve areas of life which have not until now been readily quantifiable, every detail of a human commodity’s ongoing “development” must be electronically recorded and tracked, preferably in real time.

So it was that, in 2009, The Commonwealth’s leaders committed themselves to “the strengthening and creation of partnerships and networks to increase development effectiveness, emphasising high-impact initiatives with clearly measurable outcomes”. (67)

Secretary general Scotland wrote in 2021: “Continuing progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals is vital to building the world we want to see, and to do so we need to be able reliably and progressively to measure and monitor the ways in which young people live, learn and work in our communities”. (68)

“Impactful youth development programmes” (69) and associated “pragmatic remote evaluation tools” (70) are very much part of the agenda of The Commonwealth’s 2020 report.

Indeed, its full title is “Global Youth Development Index and Report” and alongside its enlightening articles are pages of statistical data.

Speaking before the report’s release, Scotland began with the usual platitudes about giving young people “a future that is more just, inclusive, sustainable and resilient”.

But then she added: “By measuring their contributions and needs with hard data, our advocacy for their development becomes more powerful, and we are then able incrementally to increase the positive impact…”

“The measurement of differential impact is critical”, declares the brochure’s Executive Summary. (71)

The twisted mentality behind the impact industry is hard to take in. Everything in life is reduced to statistical “scores” linked to financial return.

In an opening section of the brochure, a member of the Commonwealth Secretariat reports that “the scores for HIV, self-harm, alcohol abuse and tobacco consumption rates improved by less than 2 per cent each”. (72)

In the warped impact world, people’s mental health becomes a source for potential profit.

One article states: “Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health was becoming better understood and prioritised as a development outcome”. (73)

A development outcome? Really?

And here again the parasites seem to find “the pandemic” has served their pecuniary purposes, with the brochure informing us that “mental health has gained even greater significance since the COVID-19 pandemic” (74) and has been “yielding positive outcomes”. (75)

As we have previously shown, there is a strong proven connection between impact capitalism, the UN Sustainabile Development Goals and the “intersectionality” which is such a key part of the contemporary corporate-friendly cult of “wokeness”.

So it is no surprise that The Commonwealth is proud to have produced “the first global index on youth inclusion, with an important emphasis on gender equality”. (76)

We learn: “The domain is designed to measure multiple aspects of inclusion, recognising that the factors that create social exclusion for young people are diverse and intersectional and have wide-ranging impacts”. (77)

Writing about “applying inter-sectionality”, Commonwealth collaborator Puja Bajad explains: “Participation processes and frameworks can be responsive only if they consider the intersections of race, sexuality, gender, class, caste, ethnicity and economic status that could obstruct inclusive youth participation”. (78)

Beneath this language lurks, as ever, the underlying reality of “development partners” who want to “invest to optimise the ‘youth dividend’ by pursuing innovation, creativity and risk for youth cohorts to participate” and who need to “build an evidence base to show the impact of youth engagement”. (79)

A rather frank guest contribution by an organisation called Generation Unlimited introduces The Youth Agency Marketplace (Yoma), “a digital ecosystem platform where youth grow, learn and thrive through engaging in social impact initiatives and are linked to skilling and economic opportunities”. (80)

A rather frank guest contribution by an organisation called Generation Unlimited introduces The Youth Agency Marketplace (Yoma), “a digital ecosystem platform where youth grow, learn and thrive through engaging in social impact initiatives and are linked to skilling and economic opportunities”. (80)

It says: “Initiatives on the platform align with the SDGs, creating a vibrant youth marketplace for skills, digital profiles, employment and entrepreneurship.

“Yoma offers the opportunity for public and private partner organisations to reach and interact with youth to support and tap their potential”. (81)

To tap young people’s potential is apparently to “create value” – to make money in anybody else’s terms!

Worse still, this “digital ecosystem platform” aims to push its victims still further into the nightmare future of digital tyranny being rolled out under the Great Reset.

The article reveals: “As youth engage in the opportunities offered by Yoma, their active involvement and skills acquired is recorded on a verifiable digital CV with certified credentials using blockchain technology.

“Their efforts are further rewarded and incentivised with the platform’s digital currency (ZLTO), a digital token, that can be spent in the Yoma marketplace to purchase goods and services”. (82)

5. Vast fortunes

We have written on this site about the similarities between Klaus Schwab’s public-private “stakeholder capitalism” and the economic model of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

But the arrangement was also a feature of the economic “liberalism” practised by the British Empire.

By the start of the 1600s it was clear to the merchants of London that “there were big profits to be made in overseas trade”, as historian Christopher Hill writes. (83)

The East India Company, formed in 1601, was making a profit of 500% by 1607 and basically administered India in a public-private arrangement with the British state until 1858.

Hill notes that the company, like The Royal African Company, “enjoyed the peculiar patronage of the government” and that both were “deeply involved in politics”. (84)

In A People’s History of England, A.L. Morton describes the firm as “the real founder of British rule in India”, (85) being “the first important joint stock company” which allowed it “a continuous development”. (86)

In A People’s History of England, A.L. Morton describes the firm as “the real founder of British rule in India”, (85) being “the first important joint stock company” which allowed it “a continuous development”. (86)

A “sustainable development” in today’s language, perhaps?

The East India Company (whose flag is pictured here) was also notoriously corrupt and violent, to the point that in the 18th century even the company’s own directors were forced to condemn the fact that “vast fortunes” had been obtained by “the most tyrannic and oppressive conduct that was ever known in any country”. (87)

Enabling the advance of private profit and the accumulation of “vast fortunes” is unmistakably a key part of The Commonwealth’s mission.

In the words of its own dead-eyed corporate blurb, this means that it should “play a dynamic role in promoting trade and investment so as to enhance prosperity, accelerate economic growth and development and advance the eradication of poverty in the 21st century”. (88)

In 1997 it explicitly insisted that “wealth creation requires partnerships between governments and the private sector” (89) which it trendily decided to call “smart partnerships”. (90)

It seeks “more effective ways of meeting infrastructure financing gaps that engage the private sector” (91) and has set up schemes such as the Commonwealth Private Investment Initiative “to support a greater flow of investment to developing member countries”. (92)

Despite all its pseudo-environmental talk, The Commonwealth has always been adamant that “to achieve sustainable development, economic growth is a compelling necessity”. (93).

It warned sternly, in the same 1989 statement: “Environmental concerns should not be used to introduce a new form of conditionality, nor as a pretext for creating unjustified barriers to trade”.

At the end of the 1990s The Commonwealth seems to have become a little rattled by the rise of the anti-globalisation movement and felt the need to announce: “Globalisation is creating unprecedented opportunities for wealth creation and for the betterment of the human condition. Reduced barriers to trade and enhanced capital flows are fuelling economic growth”. (94)

Recognising that there were some issues arising from globalisation, it insisted: “The solution does not lie in abandoning a commitment to market principles or in wishing away the powerful forces of technological change. Globalisation is a reality and can only increase in its impact.

“We fully believe in the importance of upholding labour standards and protecting the environment. But…”

Forgive us an ironic chuckle here.

“… But these must be addressed in an appropriate way that does not, by linking them to trade liberalisation, end up effectively impeding free trade and causing injustice to developing countries”. (95)

Good grief! We can’t have free trade impeded! What about the poor natives in Africa who are simply crying out to have their economic potential developed by our friends at the World Bank?

In more recent years The Commonwealth has, of course, been greatly excited by the profitable potential of “climate finance”, looking forward in 2009 to “a Copenhagen Launch Fund starting in 2010 and building to a level of resources of US$10 billion annually by 2012”. (96)

It “places a great emphasis on facilitating the capacity development of member countries to access climate finance” (97) and likes the idea of “governments exploring with development banks in facilitating the provision of more accessible financing facilities for youth-led climate research projects”. (98)

“A total of USD$28 million of climate finance with another USD$460 million in the pipeline”

To this public-private effect, it is proud to have set up the Commonwealth Climate Finance Access Hub, which “deploys climate finance experts in government departments”. (99)

We learn from the Commonwealth Innovation website that “in its short time of operation, the Hub has already recorded remarkable results for Commonwealth countries, securing a total of USD$28 million of climate finance with another USD$460 million in the pipeline”.

The site provides helpful links to two completely different climate finance organisations.

One is the Global Environment Facility, which was initially set up in 1992 to promote “sustainable development” within the structure of the World Bank.

The other is Adaption Fund, an organisation “helping developing countries build resilience and adapt to climate change”, whose sole trustee is… the World Bank.

Oh. Perhaps “completely different” wasn’t quite the right term.

6. Devoted to deceit

Since its beginnings, the Commonwealth has been based on a double deception, a concealment on two levels.

Behind the facade of “a mutually supporting family of nations and peoples” (100) is the reality of a ruthless empire designed to grab the land, loot the resources and profit from the “human capital” of the peoples it has annexed.

And hiding behind that empire have always been the nefarious financial interests historically centred in that great stinking den of greed and corruption, the City of London.

Quigley writes that Britain became “the center of world finance as well as the center of world commerce”. (101).

And he notes that one of the key factors in Britain’s historical global domination was “the skill in financial manipulation, especially on the international scene, which the small group of merchant bankers of London had acquired in the period of commercial and industrial capitalism and which lay ready for use when the need for financial capitalist innovation became urgent”. (102)

He describes them as being “devoted to secrecy and the secret use of financial influence in political life” and as “persons of tremendous public power who dreaded public knowledge of their activities”. (103)

The Commonwealth likes to boast of its “enduring values”, depicting itself as “an organisation which draws on its history”. (104)

The Commonwealth likes to boast of its “enduring values”, depicting itself as “an organisation which draws on its history”. (104)

Its secretary general, Scotland (pictured), writes of the “dynamism combined with continuity” involved in “maintaining the familiar harmony, yet developing it in ways never before attempted”. (105)

She says that the “brief yet visionary” 1949 London Declaration which brought into being the Commonwealth we know today “meant that nothing had changed and yet everything had changed”. (106)

It is interesting to consider this remark in the context of the 27 “partner” organisations listed by her body on its Commonwealth Innovation platform.

Sitting proudly at the top of the list is the World Health Organization, followed by the African Development Bank Group, the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, the United Nations and five of its various sub-organisations.

We also find the likes of Bloomberg Philanthropies (founded by US billionaire Michael Bloomberg), the International Trade Centre (“a multilateral agency with a joint mandate with the World Trade Organization and the United Nations through the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development”), Global Innovation Fund, an impact investment specialist, and NDC Partnership, a big player in the world of “climate finance”.

Alongside the other connections revealed in this article, this confirms that what hasn’t changed is that financial interests still very much direct the activities of the empire.

What has changed is that the British empire is no longer the principal “public-private” instrument through which these interests pursue their agenda of all-inclusive exploitation.

Instead, we can discern the vague outlines of a global network or entity whose centre is difficult to identify but whose key institutions clearly include the United Nations, the WHO, the WEF, the World Bank and the less-discussed Bank for International Settlements, as well as the good old Commonwealth.

This contemporary entity is more than happy to use the “nice guy” deceit first developed in the days of the original British Empire in order to hide its existence and its activities.

The philanthropic, do-gooding, sustainably “woke” posturing of the institutions behind which it hides is meant to see off the possibility of any serious scrutiny or criticism.

Indeed, this device even enables it to rally to its support the very people (on the “left”) who should be opposing it.

Not only is their potential dissent disabled, but they are also used to attack the entity’s remaining enemies from what appears to be the moral high ground.

Anyone who dares to expose and challenge their sugar-coated sociopathy is likely to be denounced as a selfish, reactionary, right-wing conspiracy theorist.

After all, what decent citizen could possibly have a problem with an empire which is “a compelling force for good” working to “eradicate poverty”, to bring about “peace and harmony” and “a better world for our children”?

Subscribe to The Acorn

Subscribe to The Acorn

Notes

1. John Ruskin, ‘Athena Keramitis’, The Genius of John Ruskin: Selections from his Writings, ed. by John D. Rosenberg (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1964), p. 361.

2. Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope: A History of The World in Our Time (New York: Macmillan, 1966. Reprint. New Millennium Edition), p. 31.

3. Quigley, p. 83.

4. Patricia Scotland, secretary-general of the Commonwealth, Foreword, Commonwealth Declarations (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2019), p. ix.

5. Kenya White Paper, 1923, cit; Quigley, p. 96.

6. Quigley, p. 109.

7. Quigley, p. 379.

8. Quigley, p. 365.

9. Declaration Signed by the Five Prime Ministers, United Kingdom, 1944, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 2.

10. The Declaration of Commonwealth Principles Singapore, 1971, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 9.

11. The Goa Declaration on International Security, India, 1983, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 16.

12. The Coolum Declaration, Australia, 2002, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 53.

13. Patricia Scotland, Foreword, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020 (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2021), p. vi.

14. Scotland, Commonwealth Declarations, p. ix.

15. Scotland, Commonwealth Declarations, p. ix.

16. The Aso Rock Commonwealth Declaration Nigeria, 2003, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 55.

17. The Aso Rock Commonwealth Declaration Nigeria, 2003, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 56.

18. The Coolum Declaration Australia, 2002, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 51.

19. Colombo Declaration on Sustainable, Inclusive and Equitable Development, Sri Lanka, 2013, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 88.

20. Gustavo Esteva, ‘Development’, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, ed. Wolfgang Sachs (London/New York, Zed Books, Second Edition, 2010, first published 1992), p. 3.

21. Esteva, ‘Development’, The Development Dictionary, p. 5.

22. Esteva, ‘Development’, The Development Dictionary, p. 13.

23. Wolfgang Sachs, ‘Environment’, The Development Dictionary, p. 28.

24. The Nassau Declaration on World Order, The Bahamas, 1985, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 19.

25. Declaration by Commonwealth Prime Ministers United Kingdom, 1951, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 6.

26. The Nassau Declaration on World Order, The Bahamas, 1985, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 17.

27. The Nassau Declaration on World Order, The Bahamas, 1985, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 19.

28. Dr Musarrat Maisha Reza, Chair, Commonwealth Students’ Association, and Lecturer, University of Exeter, UK, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 72.

29. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 134.

30. Mamta Murthi, Vice President of Human Development, World Bank, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 75.

31. Murthi, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 75.

32. Executive Summary, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. xxvi.

33. Swartz and Krish Chetty, Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa, Youth Education and Employment in the Digital Economy, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 117.

34. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 134.

35. The Coolum Declaration Australia, 2002, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 54.

36. Commonwealth Cyber Declaration, United Kingdom, 2018, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 92.

37. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, pp. 97-98.

38. Executive Summary, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. xxvi.

39. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 16.

40. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 16

41. Swartz and Krish Chetty, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 117.

42. Swartz and Krish Chetty, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 120.

43. Swartz and Krish Chetty, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, pp. 121-22.

44. The Aso Rock Commonwealth Declaration, Nigeria, 2003, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 55.

45. Kampala Declaration on Transforming Societies to Achieve Political, Economic and Human Development, Uganda, 2007, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 66.

46. Commonwealth Cyber Declaration, United Kingdom, 2018, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 93.

47. World Bank, Assault on World Poverty (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), p. 16, cit. Arturo Escobar, ‘Planning’, The Development Dictionary, p. 153.

48. C. Douglas Lummis, ‘Equality’, The Development Dictionary, p. 46.

49. Majid Rahnema, ‘Poverty’, The Development Dictionary, p. 187.

50. The Harare Commonwealth Declaration, Zimbabwe, 1991, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 29.

51. Esteva, ‘Development’, The Development Dictionary, p. 13.

52. The Fancourt Commonwealth Declaration on Globalisation and People-Centred Development, South Africa, 1999, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 49.

53. The Coolum Declaration, Australia, 2002, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 53.

54. Murthi, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 75.

55. Scotland, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. vi.

56. Scotland, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. vi.

57. The Magampura Declaration of Commitment to Young People, Sri Lanka, 2013, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 83.

58. The Magampura Declaration of Commitment to Young People, Sri Lanka, 2013, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 83.

59. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 2.

60. Declaration on the Commonwealth Connectivity Agenda for Trade and Investment, United Kingdom, 2018, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 97.

61. A Declaration on Young People, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 2009, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 77.

62. Chris Morris, Head of NGO and Civil Society Center and Concurrent Manager of the Asian Development Bank’s Youth for Asia initiative, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 73.

63. Tijani Christian, Chairperson of the Commonwealth Youth Council, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. viii.

64. Bora Kamwanya, Deputy Secretary General, Pan-African Youth Union, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 71.

65. Ottawa Declaration on Women and Structural Adjustment Zimbabwe, 1991, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 33.

66. Florence Nakiwala Kiyingi, chair of the Commonwealth Youth Ministerial Task Force, Foreword, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. vii.

67. The Declaration of Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 2009, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 74.

68. Scotland, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. vi.

69. Tim Conibear of Waves for Change and Sallu Kamuskay and Margaedah Michaella Samai of the Messeh Leone Trust with the Wave Alliance Sierra Leone, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 83.

70. Conibear et al, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 82.

71. Executive Summary, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. xxviii.

72. Layne Robinson, Head of Social Policy Development, Economic Youth and Sustainable Development Directorate, Commonwealth Secretariat, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. x.

73. Conibear et al, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 82.

74. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 80.

75. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 81.

76. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 9.

77. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 9.

78. Puja Bajad, Consultant, youth and social policy, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 63.

79. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 31.

80. Generation Unlimited, The Youth Agency Marketplace (Yoma): Designed by youth and

led by youth, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 145.

81. Generation Unlimited, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 145.

82. Generation Unlimited, Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 145.

83. Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution 1603-1714 (London: Sphere, 1969), p. 42.

84. Hill, p. 188.

85. A.L. Morton, A People’s History of England (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1995), p. 174.

86. Morton, p. 175.

87. Morton, p. 261.

88. Edinburgh Commonwealth Economic Declaration, United Kingdom, 1997, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 46.

89. Edinburgh Commonwealth Economic Declaration United Kingdom, 1997, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 40.

90. Edinburgh Commonwealth Economic Declaration, United Kingdom, 1997, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 44.

91. Perth Declaration on Food Security Principles, Australia, 2011, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 81.

92. The Millbrook Commonwealth Action Programme on the Harare Declaration, New Zealand, 1995, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 38.

93. Langkawi Declaration on the Environment Malaysia, 1989, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 23.

94. The Fancourt Commonwealth Declaration on Globalisation and People-Centred Development, South Africa, 1999, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 47.

95. The Fancourt Commonwealth Declaration on Globalisation and PeopleCentred Development, South Africa, 1999, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 48.

96. The Commonwealth Climate Change Declaration, Trinidad and Tobago, 2009, Commonwealth Declarations, p. 71.

97. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 170.

98. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 170.

99. Global Youth Development Index and Report 2020, p. 171.

100. Scotland, Commonwealth Declarations, p. ix.

101. Quigley, p. 45.

102. Quigley, pp. 33-34.

103. Quigley, p. 34.

104. The Coolum Declaration, Australia, 2002, Commonwealth Declarations, pp. 52-53.

105. Scotland, Commonwealth Declarations, p. ix.

106. Scotland, Commonwealth Declarations, p. ix.

0 Comments