How landlords became monsters

by Nicholas Harris | Jun 7, 2023

Everyone under the age of 40 has their landlord horror story. We trade them, like old war wounds. My own, in retrospect, is rather pleasingly metaphorical, something of a capsule (or cubicle) scatological comedy. At one point, as part of a flatshare, I was renting a room in a basement flat in Finsbury Park, little more than a breezeblock bog of damp and mould. (We didn’t just have mould growing on our walls. We had mould growing on our clothes. We had mould growing in our shoes.) My abiding memory of the place is buckets of bleachy water turning green-black as we soaped the mildew off our crumbly home.

But then, at one point through our winter in this toxic swill, our bathroom ceiling caved in. The cause was wonderfully disgusting. The upstairs toilet’s “out” pipe (that’s the one bearing the shit) had been leaking into our ceiling for some interminable length of time. The waste (the shit) had then slowly seeped into the plaster and terracotta above until it became structurally unsound. One day in January, a great yawning gash opened up, and the next it fell in. It then took our landlord around two weeks to clean and repair this mess, which meant washing and bathing surrounded by the debris: shit-saturated shards of plaster and terracotta. We gave our notice in those soiled days and moved out about a month later.

It was a dispiriting exit. But even in the moment, being shat upon from a great height spoke more effectively than any mountainous graph to what is unjust about the current housing crisis. People (especially young people) live in very poor conditions, kept there by private landlords who suffer from near-criminal levels of apathy, for which we are expected to pay handsomely (my annual rent in the shit-flat was around 40% of the London Living Wage at the time — just under £10k). But the problem is, since everyone has a similar story, you’ve probably already heard it, if not lived it.

The political gravity of this situation lies not in its specifics, though, but in its generalities. Over the past week, in its house journals and attendant think tanks, the Conservative Party’s leading intellectuals have been puzzling over the fact that young people hate them. And they intimate that this has something to do with housing. They have finally listened to the housing scientists, with their heavy dossiers of facts and figures. A narrative has been acknowledged: the privatisation of state housing, followed by the transformation of property into a financial asset, has made housing and especially renting cripplingly expensive. This is far too late to redress or ameliorate — the best it can become is a historical lesson. The question that the Tories should be asking is a deeper and more threatening one. What is housing inequality doing to the political psychology of those living through it? What has it already done to us?

My answer is look to the language; look at the language we use for those we blame. Landlords — parasitic, indolent, unscrupulous landlords. In our oaths and curses, we reduce property owners to an existence of pure economic extractionism. Even landlords don’t want to be called landlords anymore. At the National Landlord Investment Show, a kind of bizarre lettings TUC, they threw around some alternatives — “Property investor”? “Accommodation provider”? — designed to help them slip back into anodyne anonymity. This cultural slander, found at all levels of output, from TikTok to acclaimed non-fiction, is the linguistic wing of something more profound. It is the first, experimental stirring of something rather anachronistic in our hyper-political age: social, tribal solidarity. Something a bit like class consciousness.

This isn’t class understood in the cod-Marxist sense, with society sliced like a layer cake between worker, owner and aristocrat. Such arbitrary categories have long been discarded. Instead, as E.P Thompson wrote in The Making of the English Working Class, class is something that “happens”. And it happens when “some men, as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against other men whose interests are different from (and usually opposed to) theirs”. Class does not pre-exist, but is spun in the language people live and create.

Since the turn of the millennium, the number of private renters has doubled to 11 million people. And this growth has been driven by the young. A third of those aged between 35 and 45 rent privately, as opposed to a tenth in 1997, a proportion which rises the younger you are. And many of those not renting are living with parents, which would make private renting their direct alternative. In other words, across income levels, private renting has become as near to an economic universality as one can find in our atomised society. But most important: under present trends, this is never going to change. High marginal tax rates, low wages and rising house prices mean that those who do not receive a large windfall from generous or dead family members will never buy a house. They will retire with a landlord, paying the bulk of their salary and perhaps their pension to a people they have spent their adult life despising. They who “love to reap where they never sowed” as Marx had it.

So much writing about our housing situation is self-pityingly childish, whinging over intrusive mezzanines and landlords’ disastrous DIY. It curries little favour with the older generation it is directed towards. But, left unchecked, the weight of sentiment is symptomatic of a more powerful force — the sense of existing in an unfair productive relationship. Like all great political vibes, it has the benefit of being both felt and true. And most transformative processes in British history have been the product of such a concoction, a wrong that can be mathematically proven and then communicably sketched.

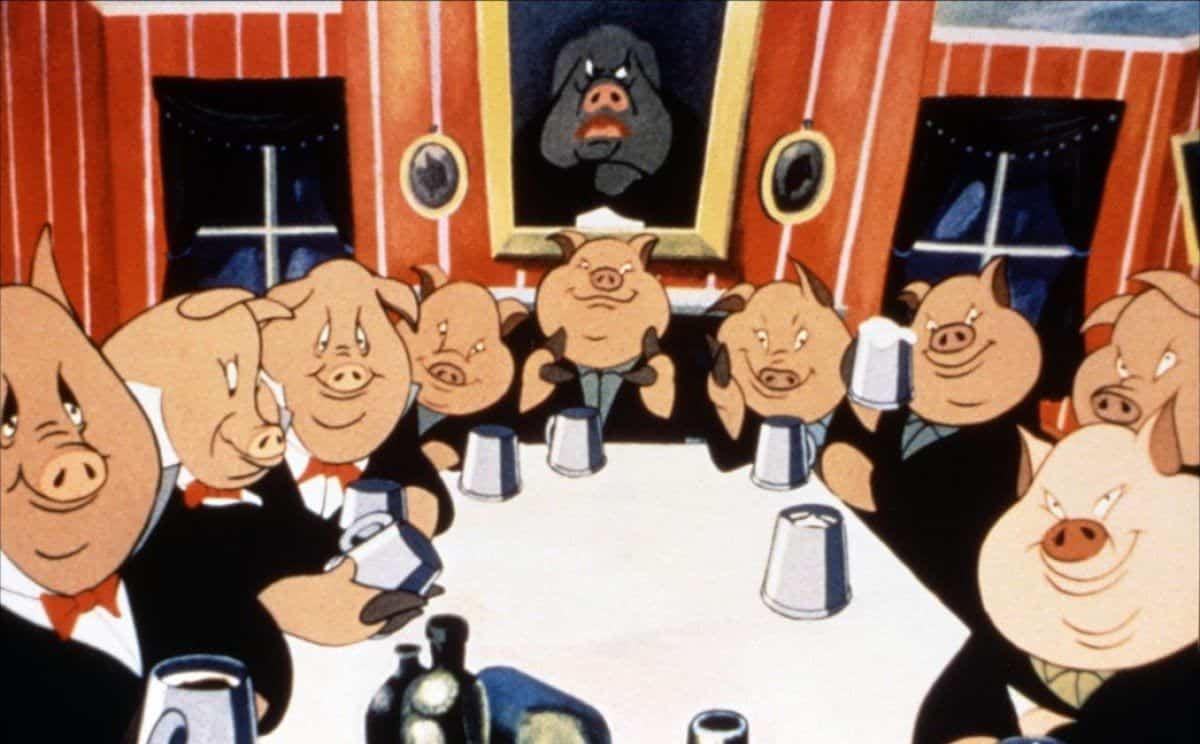

Because the popular timeline of our past is one of political nightmares, stalked by political ghouls and monsters who provide a horror mask for our deeper concerns. Recently, our darkest dreams have been peopled by crooked Luxembourgian Eurocrats. Before that, we relocked our doors and windows, woken by the march of donkey-jacketed trade unionists. But reach back into the distant interwar period and a dynamic more like our own emerges. Between the pause of one world war and resumption of the next, Britain was learning to think of itself as a “democracy” for the first time. And in this age of new and nervous egalitarianism, two of the most repellent economic caricatures in popular culture were socially-useless mountebanks: the profiteer and the rentier. Like landlords in our housing crisis, both were linked to moments of social distress which they had somehow turned to their advantage.

John Maynard Keynes was obsessed with this plutocratic individual who in his conception lived off the national debt, furnishing his Depression with public money. And the cheater, the social swindler, was the constant villain of the era’s more politicised fiction. He crops up in the otherwise sunny books of J.B Priestley, but particularly in the works of A.J. Cronin, the novelist who was most representative of the Thirties mood. (His 1937 novel The Citadel is credited by some with establishing the emotional need for an NHS.) But in his earlier book The Stars Look Down, a contest is established between an autodidactic Labour MP and his double, a profiteer-chancer who avoids war service and cheats his way into arms-trading and factory-ownership through underhand business dealings.

It was not long before such evocations reached the lips of politicians themselves. In Clement Atlee’s 1945 election broadcast, he established his opposition to those who benefitted from “private enterprise, private profit and private interests”, and who demanded “more rent, interest and profit”. The dichotomy was clearly intended to appeal to a public already aware of the difference between its productive many and its exploitative few. That Labour government was the most ambitious reforming government of the century, and brought about the greatest programme of house-building and home-improvement the country had ever seen. The Conservative government that followed only imitated and expanded upon it.

Language tracks the governing ideology of its day. After Thatcherism brought a halt to anything like the forward march of labour, Britain developed converse cultural neuroses. We gnashed at scroungers and skivers; we valorised the entrepreneur. As William Davies recently described, the working-class hero devolved from the punk, the disruptor or the organiser (Arthur Scargill), towards something more like the tamed yob, the capitalist-enthusiast (Chris Evans, Keith Allen). Britain, though, is more than capable of producing a culture that punches up. Think how harshly the word “banker” was hissed in the immediate post-2008 reconciliation. But despite the best efforts of the Occupy movement, bankers were fortified in their City towers, too lofty to organise against. Landlords, by contrast, inhabit a space much closer to home — our homes.

Today, millennials are approaching a sort of maturity. But in an arc that frustrates analysts of such matters, they stubbornly refuse to mature politically and shift Right-wards. Not only this — they are leaning markedly to the Left, especially on economic issues. Reared on a lifetime of economic vulnerability, of course they find redistribution appealing and resent the predatory potential of private ownership. Over the grim interwar, it took decades for this yearning to consummate itself. At the next election, millennials will predominate in the majority of constituencies. All those years of removal vans and disconcerting stains, of lost deposits and scratching mice, may finally find their voice.

0 Comments