Inside FICO and the Credit Bureau Cartel

by Matt Stoller | Jun 22, 2024

The attorney in a country town is as much a businessman as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis.

—William Jennings Bryan, 1896

The director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Rohit Chopra, coined the term ‘junk fee,’ and has begun restructuring how financial markets work, removing medical debt from credit reports, fostering competition in credit cards, and examining big tech’s entrance into payments. And yet, for ideological reasons, to many bankers, Chopra is a villain running a government agency full of bureaucratic demons, whose goal is to force them to do paperwork on behalf of nebulous ‘consumers.’

So it was a weird day last month when Chopra had a room full of mortgage bankers nodding their heads in furious agreement, and even angry at their own trade association for helping a monopoly take advantage of them. HousingWire’s James Kleimann and Sarah Wheeler were shocked, calling it “Must-See TV.”

The Mortgage Bankers Association annual conference started with the typical attack on the government, with President and CEO Bob Broeksmit complaining about ‘regulatory knots’ while decrying government crackdowns on junk fees. CFPB Directors often attend these conferences to communicate with the industry, and the conversations aren’t always pleasant. This one didn’t seem like it would be pleasant either. But Chopra went on stage a few hours later and discussed an increasing cost center for banks, which is the credit bureaus and FICO.

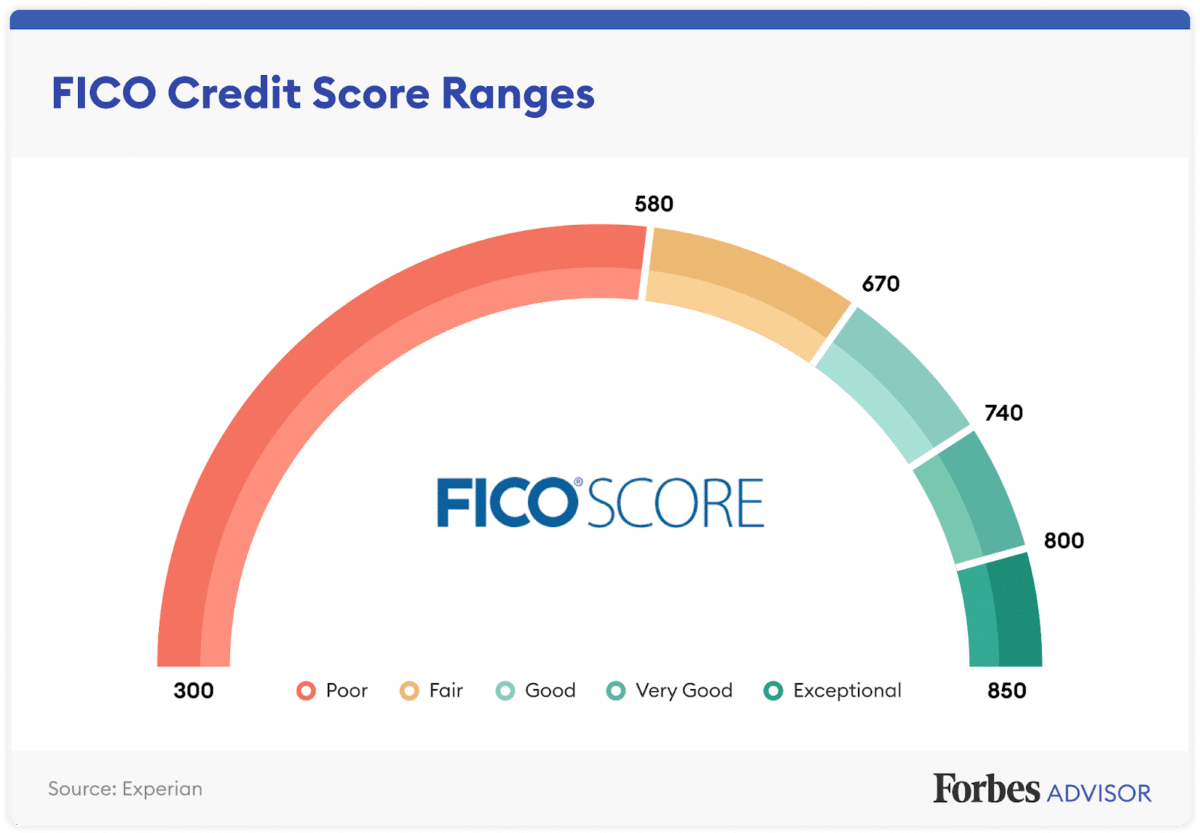

“Mortgage lenders in the U.S. increasingly face a lack of competition when it comes to accessing data and reports needed for loan origination,” he said. “In many cases, a handful of firms have cornered the market, allowing those companies to levy a tax on every mortgage application or transaction in the country.” Three firms dominate credit reporting: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. And just one company handles algorithms, the Fair Isaac Corporation, which sells the FICO score. “Mortgage lenders have shared that costs for credit reports and scores have increased,” he said. “Sometimes by 400% since 2022.” Chopra then went on to lay out some regulatory authority the CFPB has to impose price caps.

The audience, surprisingly for a free market capitalist loving group of lenders, was eating it up. Why? Well it’s the same reason app developers hate Apple and Google, or cattle ranchers dislike JBS, or producers fear Netflix. The credit bureau cartel are gatekeepers to their market. And they are being squeezed, increasingly losing money on every mortgage they issue.

Consumers pay for credit scoring, but they do so indirectly. When someone is thinking of buying a house, he or she visits a mortgage lender. That lender must buy a credit score from FICO and the bureaus to see what that person can afford. When a customer takes out a loan, that mortgage banker has to purchase another more complete report of credit information.

Even if a lender thinks the customer would be a good risk, the lender has to buy a FICO score regardless. Mortgage bankers don’t carry the capital to hold the mortgages they make. Instead they make a loan, and then send it onward to the capital markets. First, the government guarantees most mortgages through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as well as other programs for veterans and first time homebuyers. Then, the government in turn sends these guaranteed mortgages to Wall Street. This complex process relies on a standard to price the loans, and that standard is FICO, combined with the credit information from the three bureaus.

Mortgage bankers aren’t typical Wall Street bankers. While mortgage lending can be done by the big guys, real estate is an inherently localized industry with a clubby network of realtors, title insurers, and various other specialists in the home-buying process, so independent players have a strong foothold. There are roughly a thousand independent mortgage lending firms nationwide, and these lenders live everywhere. So their anger at FICO and the credit bureaus has an element of regional resentment, since they are not Wall Street traders, but are local community members trying to help people get homes.

In January of 2024, the Community Home Lenders of America discussed this dynamic with FICO, calling it a utility, which it is. The “combination of FICO’s extremely high market share, and the fact that Washington agencies require lenders to use this company’s product, means that FICO has unilateral, solid-gold market power, the type rarely seen in any US industry short of highly regulated utilities, whereby rates are set by public-utility boards or commissions.”

But the companies themselves know it and say it. In November 2011, then-CEO of Fair Isaac, Mark Greene, explained that the “network effect” of “FICO Scores . . . being sort of the standard language” and “having everybody . . . standardize on a FICO Score, that’s magic.” FICO sells 10 billion scores every year, four times the number of McDonald’s burgers and twice the number of Starbucks coffees sold annually. According to the company itself, nine out of ten lending decisions rely on FICO.

Credit scoring used to cost a relatively small amount of money, but now it can be up to $60 per pull, with the price quadrupling over the last two years for no reason whatsoever. Only one out of every ten prospective customers ends up taking out a mortgage, so higher prices fronted by mortgage bankers add up. And it’s starting to be a major expense, driving some of the mortgage lenders out of the business entirely. In other words, Chopra, though disliked for calling out junk fees charged by bankers, was actually attacking a junk fee that mortgage bankers themselves have to pay.

After his speech, Chopra and Broeksmit sat down for a public discussion, and Broeksmit pushed back on the criticism of FICO, which had led the price hike charge. And here’s where it got fascinating. Broeksmit was supposed to be representing the mortgage bankers in his association. But Chopra pointed out that, though it was a Mortgage Bankers Association event, the session itself was sponsored by FICO. “That was a wild moment right there,” recounted Wheeler on the HousingWire podcast. The head of the Mortgage Bankers Association, was being bribed by a monopolist to betray the bankers he was supposed to represent. And he was just called out for it.

Credit Is Identity

To understand the roots of this fight, we have to go back to the origins of credit reporting, which extend deep into American history. For 150 years, you could simply escape your debt by moving somewhere else, and adopting an entirely new identity. That’s the premise of the iconic American novel The Great Gatsby, the story of a mysterious East coast tycoon who has hidden his past. Today, The Great Gatsby couldn’t be written. Or if it were, it would be a one page story, in which someone runs a credit check on a rich liar named Jay Gatsby.

In other words, national credit reports are foundational to modern American society, binding us to one another financially as a nation through a network of computerized records. And that national market of identity is relatively new. Until 1970, credit reporting was localized, mostly through coops of town bankers who hired detectives to investigate borrowers, collecting gossip from snitches about who drank too much, who was a Communist, who slept around, and so forth. As the book The Naked Society noted, bureaus looked at a consumer’s “honesty, potentially dangerous habits, and manliness.” Such information was kept in large paper files, it was secret, and it could often lead to someone never being able to get a job in a certain area, and they would never know why. A Gatsby was plausible, since you could escape your debts and your very identity by leaving one state and moving to another.

Credit bureaus, like the FBI who collaborated with them, were creepy, with no limits on their data collection practices. And they saw themselves explicitly as disciplinarians. In 1968, leading credit bureau Retail Credit Corporation President Lee Burge told Congress that the “availability of record information imposes a discipline on the American citizen. He becomes more responsible for his performance whether as a driver of his car, as an employee in his job performance, or as a payor to his creditors. But this discipline is a necessary one if we are to enjoy the fruits of our economy and the present freedom of our private enterprise.”

After a lot of complaints, Congress acted. In 1970, the only woman on the Banking Committee, Leonor Sullivan, collaborated with Rep. Wright Patman and Senator William Proxmire to write and pass the Fair Credit Reporting Act. This law eliminated the collection of the gossip, which often included information on race, gender, and sexuality. FCRA gave consumers a set of rights over their credit reporting files even though these files were held by private firms, and set limits on what data could be collected and how it could be used. No longer was it acceptable to take someone’s sex life and put it in a secret file, with that information leading to the inability to get a job for years. The new law treated the credit reporting bureaus as public utilities.

FCRA was in a sense the last of the New Deal legal arrangements, passed at a moment of immense suspicion over government surveillance, part of a set of rules limiting the use of personal information by the Federal government and corporations. But FCRA also structured the national credit market, fostering the computerization of credit information nationwide, and designed to regulate the emerging industry of credit cards, which had picked up steam during the 1960s. “When a man walks into a bank to get a loan,” said a Bank of America executive in Congressional testimony, “he gives up a certain amount of privacy.” Now the bank’s ability to invade his privacy would be regulated and standardized, with the result that a loan could be done in a national market. The Gatsby era ended.

There were two thousand credit bureaus across the U.S. when FCRA passed. By the 1990s, due to this law and to a relaxation of antitrust, they consolidated into three main firms, Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. These bureaus take advantage and encourage network effects to exclude rivals. They use a “give-to-get” rule, meaning that a lender that wants credit information to determine whether to offer a loan has to give data on its customers back to the credit bureaus in return for that information. The credit bureaus, fostered by regulatory choices and consolidation, were the first wave of big data firms, laying the groundwork for corporations like Google and Facebook years later.

A different corporation, applies an algorithm to these credit bureau files to give each consumer a specific score, which is known as a FICO score. Having one number for a credit risk simplified lending and borrowing, especially as loans were split up into tranches and sold to Wall Street in large portfolios. In the 1990s, the government, through its various housing finance programs and entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, adopted FICO scores as a way to price mortgage loans. In many ways, FICO is the first artificial intelligence firm.

By the 2000s, the credit bureaus and FICO organized the national credit market, especially when it came to home buying. These firms aren’t just private entities, but have become key parts of governance. If you want to verify someone’s work and income, for instance, or manage unemployment insurance claims at scale, you use one of these bureaus, most likely Equifax (which is the successor to the Retail Credit Corporation.) That firm recently bragged it signed a billion dollar contract with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “over a billion dollars that had a price increase in it,” as well as “annual escalators.” Similarly, Experian is now running identity in our health care system with NCPDP/Experian Universal Patient Identifier.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act, the first big data governance law, has been updated multiple times, expanding it to include data furnishers, allowing consumers to get free credit information, and moving regulatory enforcement of the law in 2010 from the Federal Trade Commission to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. If you find an error in your report, you can ask for it to be corrected. However, one statutory flaw with the Fair Credit Reporting Act is that responsibility for errors rests with the consumer, not the bureau. Because of this, 44% of consumers who have looked at their credit reports found errors, which can cost credit, jobs, or government benefits.

The Original Big Data

The centralization of credit reporting and scoring had the effect of fostering market power among credit bureaus, which most consumers saw not in terms of cost, but in terms of quality and identity theft. In 2017, Equifax had one of the worst data breaches in history, one that led to Congress putting credit bureau CEOs on the hot seat in a hearing. It didn’t dent its market position, however. So even Patrick McHenry, the most favorable Wall Street Republican, criticized the bureaus. “There is no better example than the oligopoly that was created than the three that are sitting before us here today,” he said. “Our credit reporting system would be well-served by increased competition.”

The monetary cost not levied on consumers is paid by the lenders, employers, government, and other users of credit reports and identity services. And since completing a mortgage loan requires a FICO score from each one of the credit bureaus, what is known as a ‘trimerge,’ all three bureaus plus FICO have massive pricing power. FICO tends to lead the price increase, hiking its algorithm cost, which then allows credit bureaus to raise what they charge. These four firms are all doing quite well, which is odd, considering that mortgage lending is way down due to higher interest rates.

FICO, for instance, offers amazing returns to investors. FICO’s CEO, Will Lansing, has noted publicly that his firm has “quite a bit of discretion in whether we want our margins to be higher or lower or where they are.” In 2023, its operating margin was 51%, and it spent just $159 million on research vs $407.3 million of stock buybacks.

The three bureaus are benefitting as well. In the first quarter of this year Equifax CEO’s Mark Begor in a call with investors, talking about mortgage credit products stated: “Obviously, we take price up every year, which we did in 2024.” TransUnion’s CFO Ted Cello, similarly, in an investor call said “For 2024, we expect mortgage inquiries to be down roughly 5% and our revenues to increase roughly 25%, primarily” due to FICO’s pricing increase. And Experian CFO Lloyd Pitchford noted a “pricing benefit” from FICO’s price hikes. Mortgage volume at his firm collapsed by 30%, but revenue dropped by just 3%.

0 Comments