Part 1: NGO Alliances in Humanitarian Aid, Structures and Political Influence

Part 1: NGO Alliances in Humanitarian Aid, Structures and Political Influence

by The Constitutional Republic | Feb 6, 2025

Introduction

Humanitarian non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the U.S. have built a deeply entrenched, self-serving ecosystem of allied entities that allow them to expand influence, secure government contracts, and manipulate policy—all while failing to deliver results proportional to the vast sums of money they receive. These networks are deliberately structured for opacity, often including multiple tax-exempt organizations—such as public charities, social welfare groups, labor or trade associations—alongside partnerships with corporations and even for-profit subsidiaries. The primary function of these alliances is not just humanitarian aid but securing funding, increasing lobbying power, and evading accountability.

Despite their stated missions, many of these NGOs consistently fail to demonstrate meaningful impact, even as their bank accounts swell with government grants and taxpayer dollars. This report dissects how these organizations build and maintain their influence machines, leveraging dark money networks, board interlocks, and political lobbying to remain embedded in U.S. policymaking.

Case studies of Southwest Key Programs and the BCFS/FirstDay Foundation network reveal how deeply flawed and self-serving these systems have become. This report further analyzes the deceptive influence techniques used, the disturbing parallels between historical and modern NGO alliances, and the immense regulatory risks posed by this unchecked power.

Organizational Structures and Tax-Exempt Alliances

Multiple 501(c) Entities: A Legal Shell Game

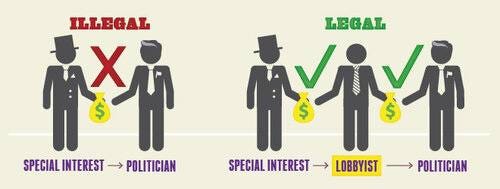

Many NGOs deliberately construct multi-entity structures to shield their finances from scrutiny while maintaining political influence. A common and highly suspect model involves pairing a 501(c)(3) public charity—which can collect tax-deductible donations and government grants—with a 501(c)(4) social welfare arm, which allows for unlimited lobbying and issue advocacy under the guise of public service.

This setup lets these organizations have it both ways: The 501(c)(3) maintains a benevolent public image while the 501(c)(4) does the political dirty work—lobbying for laws that ensure perpetual funding, favorable regulations, and protection from oversight. Meanwhile, corporations and undisclosed high-dollar donors can funnel money into these networks without revealing their identities, thanks to the IRS’s lenient donor disclosure rules for 501(c)(4)s. This means that millions, if not billions, of dollars flow into the political arena under the cover of “humanitarian work,” escaping public accountability.

Labor and Trade Associations: Co-opting Political Power for NGO Gains

NGOs further entrench themselves in the political landscape by embedding within 501(c)(5) labor unions and 501(c)(6) trade associations, allowing them to mobilize large-scale lobbying operations under the radar. Unlike 501(c)(3)s, these entities can dedicate nearly all their resources to lobbying efforts, making them powerful advocacy weapons.

These alliances are not formed for purely charitable or humanitarian reasons but to amplify financial and legislative control. A coalition of NGOs joining forces with a 501(c)(6) trade association ensures they can lobby with near-total impunity, utilizing loopholes to direct vast sums toward political influence campaigns. This creates an ecosystem where supposed humanitarian organizations are operating with the same level of political power as corporate lobbying firms.

This structure exposes a fundamental flaw in U.S. tax law: A nonprofit should not be engaging in the same levels of lobbying and influence-buying as a major corporation—yet that is exactly what is happening, and very few watchdogs are paying attention.

Private Foundations and Donor Networks: Whitewashing Influence

International humanitarian NGOs routinely manipulate their finances through alliances with private foundations and donor-advised funds that act as legal money-laundering mechanisms for influence operations. These foundations are not merely funding “research” or “policy initiatives”—they are shaping legislation, stacking committees, and determining how billions in taxpayer funds are allocated.

For example, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, one of the most powerful philanthropic entities in the world, has been known to fund policy research that aligns with its private interests—effectively creating government-backed initiatives through third-party NGOs without democratic input.

These foundations have also found ways to sidestep restrictions on direct lobbying. Since private foundations technically cannot engage in direct lobbying, they instead pour money into affiliated 501(c)(3)s, which then distribute funds to a related 501(c)(4) arm—creating a legally gray but highly effective influence pipeline.

One clear example of this deliberate obfuscation is Save the Children, which quietly operates Save the Children Action Network (SCAN), a 501(c)(4) political arm, to lobby for legislation under the guise of child advocacy. This is not about helping children; it is about controlling policy and ensuring their network remains politically relevant and financially stable.

A System Designed for Self-Preservation

While NGOs claim to exist for the greater good, their structural designs reveal something entirely different: A well-oiled, self-reinforcing machine that maximizes funding, minimizes oversight, and entrenches political influence—all while failing to deliver measurable results for the American people.

The expansion of multi-entity structures, corporate entanglements, and untraceable financial flows should concern every taxpayer, donor, and policymaker. These NGOs have become political operators first and humanitarian actors second, and without serious regulatory intervention, they will continue to siphon public funds and shape policies without accountability.

Coalitions and Umbrella Groups:

NGOs also form coalitions – sometimes incorporated as nonprofits themselves – to amplify their collective voice. For instance, InterAction is a U.S.-based alliance of international relief and development NGOs that coordinates advocacy on foreign aid and humanitarian policy. Such umbrella organizations often take on a 501(c)(3) or 501(c)(4) status depending on their advocacy role. (InterAction is a 501(c)(3) that does some lobbying; it reported spending on advocacy, though relatively modest, to preserve its charitable status.) Similarly, Refugee Council USA is a coalition of resettlement agencies that lobbies Congress and the Administration on refugee admissions policy. These networks demonstrate how NGOs band together – effectively functioning as a 501(c)(6)-like association of nonprofits – to speak with a unified voice on policy issues (e.g. advocating for higher refugee quotas or humanitarian funding).

Alliances with Corporations and For-Profit Entities: A Profit-Driven Humanitarian Complex

Humanitarian NGOs routinely blur the line between public service and profit-seeking ventures, forming alliances with corporations and for-profit entities to expand their financial and political reach. These relationships are not just about resources; they function as a mutually beneficial arrangement where corporations gain political favor, and NGOs gain expanded influence under the pretense of advocacy.

Corporate Funding and Strategic Partnerships: Masking Political Influence as Philanthropy

Corporations pump millions into NGOs, using charitable grants, cause-marketing campaigns, and strategic alliances to buy influence. These partnerships don’t just help NGOs expand their reach—they serve as a cover for political deal-making. In return for corporate support, NGOs lend credibility to corporate lobbying efforts, acting as intermediaries that soften public resistance to corporate-friendly legislation.

For example, an NGO engaged in disaster relief might partner with a logistics company to handle aid delivery, allowing that company to secure lucrative government contracts while simultaneously lobbying Congress for expanded disaster aid funding—funding that ultimately benefits both the NGO and its corporate partner. This creates a cycle where humanitarian aid becomes a pretext for increasing government expenditures that directly benefit private sector players, all while masking the transactional nature of the relationship.

The IRS’s already lax oversight of 501(c)(4) organizations allows corporations to exploit this dynamic even further. By funneling money through these entities, businesses can engage in political advocacy without publicly disclosing their involvement. What the public sees as philanthropy is, in reality, a sophisticated form of influence-peddling that circumvents campaign finance laws and ethical oversight.

For-Profit Subsidiaries and Contractors: Exploiting Government Contracts for Financial Gain

NGOs do not merely rely on donations and grants; they have found ways to integrate themselves directly into the government contracting system, creating a circular flow of taxpayer money that sustains their operations. This is achieved through for-profit subsidiaries, subcontracting schemes, and corporate partnerships that obscure financial accountability.

A glaring example of this dubious practice is the BCFS network, which funneled $4.2 billion in federal funds through a FEMA COVID-19 testing and vaccination contract to a private staffing company, Krucial Staffing LLC. In this arrangement, BCFS—a so-called nonprofit—acted as the middleman, collecting massive sums from the federal government while outsourcing the actual work to a for-profit contractor.

This arrangement creates an illusion of efficiency while enabling financial engineering that maximizes profit. If an NGO charges the government an inflated rate compared to what it actually pays a subcontractor, it can pocket the difference as surplus revenue, under the guise of administrative costs. This type of setup is alarmingly common and effectively turns government aid programs into cash cows for well-connected NGOs. Instead of fulfilling their missions, these organizations have mastered the art of using federal contracts to perpetuate their own financial growth—a reality few policymakers or taxpayers realize.

These contract-based financial structures have more in common with military contractors than with true humanitarian organizations, yet they continue to operate under the nonprofit label, shielded from the financial scrutiny that private businesses would face.

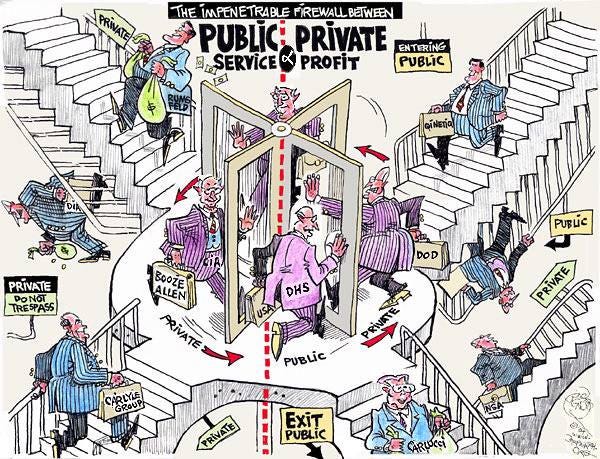

Board Interlocks and Revolving Doors: The Same Power Brokers in Different Seats

The corporate infiltration of NGOs is not limited to financial partnerships—it extends into governance, where executives rotate between nonprofit boards, corporate advisory panels, and lobbying firms. This tight-knit web of influence ensures that NGOs remain aligned with corporate and political interests rather than independent humanitarian goals.

A clear case of this revolving-door dynamic is Southwest Key Programs, whose founder, Dr. Juan Sanchez, sat on the board of UnidosUS (formerly the National Council of La Raza)—a major Latino advocacy group. This gave Southwest Key direct access to powerful advocacy networks that influence immigration policy at the federal level. However, when allegations of financial mismanagement and child abuse scandals within Southwest Key shelters surfaced, UnidosUS quickly severed ties, revealing just how fragile and politically convenient these alliances are.

The pattern is repeated across major NGOs: executives jump from government positions to nonprofit boards, from corporate CSR panels to lobbying firms, all while claiming to serve the public interest. In 2023 alone, all four of Southwest Key’s registered lobbyists were former government officials, further proving that these organizations have become extensions of the very political system they claim to be independent from.

This interchangeability between NGO executives, corporate lobbyists, and government officials enables these organizations to operate with near-total impunity, using insider access to steer funding, shape regulations, and push self-serving policy agendas.

Indirect Corporate Influence: Dark Money Channels Disguised as Social Responsibility

Corporations routinely exploit nonprofit status to channel funds into politically aligned causes while avoiding public scrutiny. Instead of direct lobbying, companies funnel money into 501(c)(4) and 501(c)(6) entities, effectively laundering their influence through nonprofit networks.

For example, a technology company interested in increasing immigration quotas might quietly fund a 501(c)(4) coalition advocating for refugee resettlement, which indirectly supports the company’s goal of expanding its talent pool. The NGO receives funding to lobby for its cause, the corporation benefits from expanded immigration policies, and the entire transaction remains legally hidden from public view.

This strategy allows corporations to wield enormous political power without leaving fingerprints. Because 501(c)(4) entities are not required to disclose donors, a company can finance issue advocacy campaigns, legislative proposals, or even activist movements while maintaining plausible deniability.

Additionally, the tax advantages of this model are undeniable. Donations to 501(c)(3) charities are tax-deductible, while lobbying expenses are not. This loophole enables companies to increase their influence without affecting their taxable income, essentially converting what would be a lobbying expense into a charitable contribution.

A prime example of this covert influence operation can be seen in the pharmaceutical industry’s partnership with global health NGOs. A major drug company might finance an NGO’s HIV treatment project while simultaneously lobbying Congress for increased global health funding. The result? Both the NGO and the corporation profit, but the public remains unaware of the backroom deal-making that made it happen.

An Engineered System of Influence and Self-Preservation

While NGOs claim to be independent actors committed to humanitarian aid, their financial structures and corporate partnerships tell a different story. These organizations have built an ecosystem that operates much like a political lobbying firm, ensuring their continued influence, financial security, and policy control.

Regulators must acknowledge the reality of this rigged system: humanitarian aid has become a political enterprise, where taxpayer money flows freely, oversight is nonexistent, and influence is sold to the highest bidder. The American people must start paying attention—because these NGOs certainly are, and they’re using every tool at their disposal to maintain power.

Subscribe to The Constitutional Republic

References:

Organizational Structures and Tax-Exempt Alliances

- IRS Guidelines on 501(c) Organizations:

- Save the Children Action Network (SCAN) Advocacy Mission:

- InterAction – Alliance of Humanitarian NGOs:

- Refugee Council USA Coalition Advocacy:

- U.S. IRS Tax Exemption Rules for Foreign NGOs:

Alliances with Corporations and For-Profit Entities

- Southwest Key Programs Financial Reports & Board Compensation:

- BCFS Health and Human Services Contracting with FEMA and COVID-19 Response:

- FirstDay Foundation & BCFS Structure: www.firstdayfoundation.org/about/

- IRS Regulations on Nonprofit-Owned LLCs: www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/eotopicb99.pdf

- The National Council of La Raza (UnidosUS) Breaks Ties with Southwest Key: www.npr.org/2018/09/22/unidosus-drops-southwest-key

- American Thinker Investigation on FirstDay Foundation Financial Reserves: www.americanthinker.com/articles/2023/firstday_foundation_slush_fund.html

0 Comments