School of the Americas protest, November 2006. (Ashleigh Nushawg, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The FBI ‘Visits’ Scott Ritter

by Andrew P. Napolitano | Aug 15, 204

Among the lesser-known holes in the U.S. Constitution cut by the Patriot Act of 2001 was the destruction of the “wall” between federal law enforcement and federal spies.

The wall was erected in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which statutorily limited all federal domestic spying to that which was authorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA).

The wall was intended to prevent law enforcement from accessing and using data gathered by America’s domestic spying agencies.

Government spying is rampant in the U.S., and the feds regularly engage in it as part of law enforcement’s well-known antipathy to the Fourth Amendment.

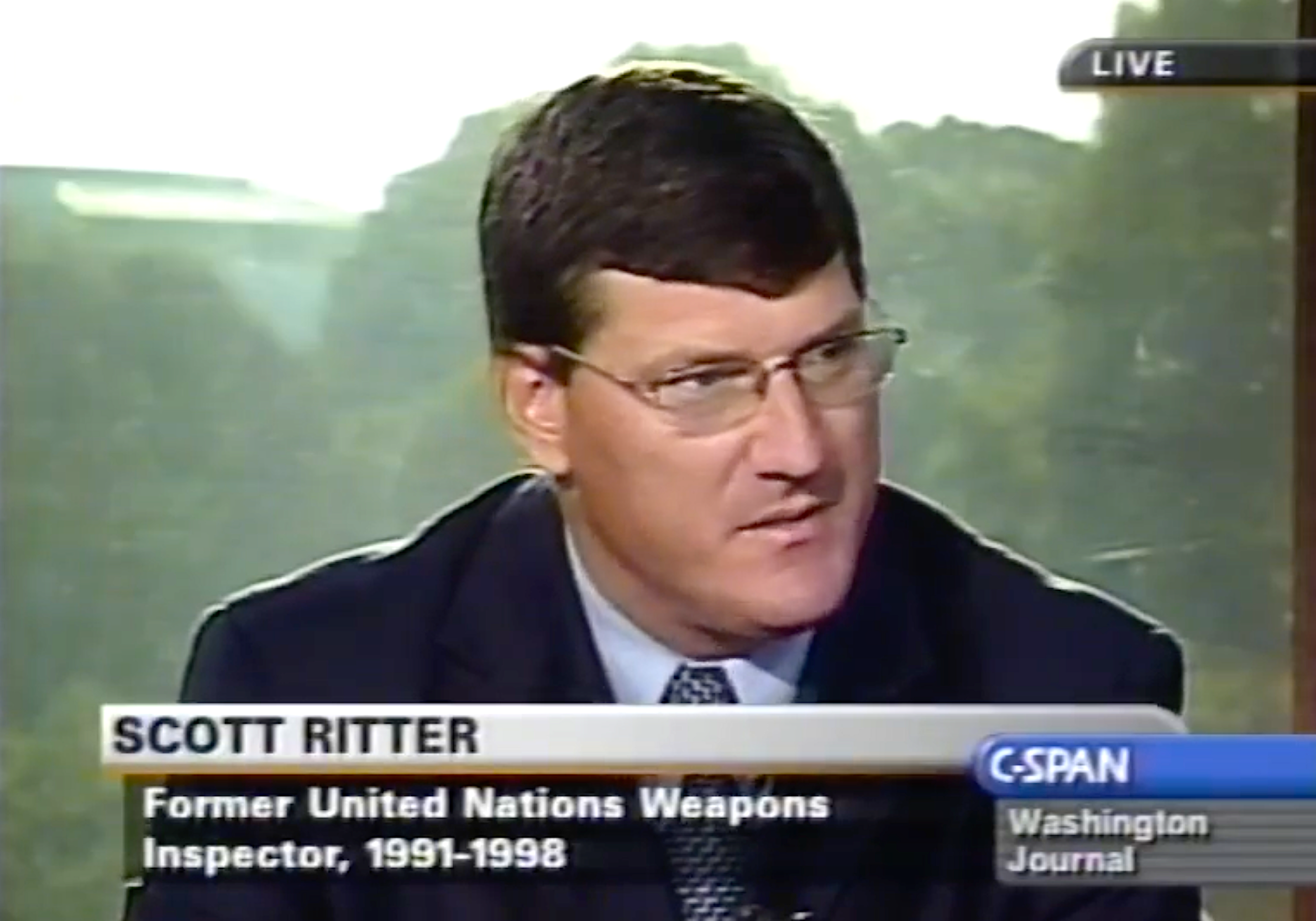

Last week, the F.B.I. admitted as much when it raided the home of former chief U.N. weapons inspector Scott Ritter. Scott is a courageous and gifted former Marine. He is also a fierce and articulate antiwar warrior.

Here is the backstory.

After President Richard Nixon resigned the presidency, Congress investigated his use of the F.B.I. and C.I.A. as domestic spying agencies. Some of the spying was on political dissenters and some on political opponents. None of it was lawful.

What is lawful spying? The modern Supreme Court has made it clear that domestic spying is a “search” and the acquisition of data from a search is a “seizure” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

That amendment requires a warrant issued by a judge based on probable cause of crime presented under oath to the judge for a search or seizure to be lawful. The amendment also requires that all search warrants specifically describe the place to be searched and the person or thing to be seized.

Colonial-Era General Warrants

The language in the Fourth Amendment is the most precise in the Constitution because of the colonial disgust with British general warrants. A general warrant was issued to British agents by a secret court in London. General warrants did not require probable cause, only “governmental needs.” That, of course, was no standard whatsoever, as whatever the government wants it will claim that it needs.

General warrants authorized government agents to search wherever they wished and to seize whatever they found — stated differently, to engage in fishing expeditions.

FISA required that all domestic spying be authorized by the new and secret FISA Court. Congress then unconstitutionally lowered the probable cause of crime standard for the FISA Court to probable cause of speaking to a foreign agent, and it permitted the FISA Court to issue general warrants.

Yet, the FISA compromise that was engineered in order to attract congressional votes was the wall. The wall prohibited whatever data was acquired from surveillance conducted pursuant to a FISA warrant to be shared with law enforcement.

So, if a janitor in the Russian embassy was really an intelligence agent who was distributing illegal drugs as lures to get Americans to spy for him, any telephonic evidence of his drug dealing could not be given to the F.B.I.

The purpose of the wall was not to protect foreign agents from domestic criminal prosecutions; it was to prevent American law enforcement from violating personal privacy by spying on Americans without search warrants.

President George W. Bush signing the USA Patriot Act in the White House on Oct. 26, 2001. (U.S. National Archives)

Fast forward to the weeks after 9/11 when, with no serious debate, Congress enacted the Patriot Act. It removed the wall between law enforcement and spying. And by 2001, the FISA Court had on its own lowered the standard for issuing a search warrant from probable cause of speaking to a foreign agent to probable cause of speaking to a foreign person.

This, too, was unlawful and unconstitutional.

The language removing the wall sounds benign, as it requires that the purpose of the spying must be national security and the discovered criminal evidence — if any — must be accidental or inadvertent. In January 2023, the F.B.I. admitted that it intentionally uses the C.I.A. and the NSA to spy on Americans as to whom it has neither probable cause of crime nor even articulable suspicion of criminal behavior.

Articulable suspicion is the linchpin of commencing all criminal investigations. Without requiring suspicion, we are back to fishing expeditions.

The FBI’s New Rulebook

The F.B.I.’s admission that it uses the C.I.A. and the NSA to spy for it came in the form of a 906-page F.B.I. rulebook written during the Trump administration, disseminated to federal agents in 2021 and made known to Congress last year.

Last week, when F.B.I. agents searched Ritter’s home in upstate New York, in addition to trucks, guns, a SWAT team and a bomb squad, they arrived with printed copies of two years’ of Ritter’s emails and texts that they obtained without a search warrant.

Ritter in August 2002. (C-Span screenshot)

To do this, they either hacked into Ritter’s electronic devices — a felony — or they relied on their cousins, the C.I.A. and the NSA, to do so, also a felony.

But the C.I.A. charter prohibits its employees from engaging in domestic surveillance and law enforcement. Nevertheless, we know the C.I.A. is physically or virtually present in all of the 50 U.S. statehouses. And the NSA is required to go to the FISA Court when it wants to spy.

We know that this, too, is a charade, as the NSA regularly captures every keystroke triggered on every mobile device and desktop computer in the U.S., 24/7, without warrants.

The search warrant for Ritter’s home specified only electronic devices, of which he had three. Yet, the 40 F.B.I. agents there stole a truckload of materials from him, including his notes from his U.N. inspector years in the 2000s, a draft of a book he is in the midst of writing and some of his wife’s personal property.

The invasion of Scott Ritter’s home was a perversion of the Fourth Amendment, a criminal theft of his private property and an effort to chill his free speech. But it was not surprising.

This is what has become of federal law enforcement today. The folks we have hired to protect the Constitution are destroying it.

0 Comments