The Forgotten Triumph

by Roman Bystrianyk | Mar 16, 2025

Figures often beguile me, particularly when I have the arranging of them myself; in which case the remark attributed to Disraeli would often apply with justice and force: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.”

–—Mark Twain

The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest, but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Belief in myths allows the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.

— John Fitzgerald Kennedy

The problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

― Jack Sparrow

The fear of infectious disease is woven deep into the human psyche, echoing through the centuries. From ancient plagues to modern pandemics, the notion that a single, unseen entity—a bacterium or virus—could bring death on a massive scale has long haunted our collective imagination. Today, the specter of measles resurging and sweeping through populations has once again captured the public’s attention. Yet, one must ask: how much of this fear is rooted in fact, and how much is merely the echo of age-old anxieties?

The measles vaccine was first licensed in the United States in 1963. This initial version was an aluminum-precipitated vaccine derived from formaldehyde-inactivated monkey kidney cell cultures and containing the “killed” virus. However, unforeseen complications emerged, with some recipients suffering from pneumonia and encephalopathy, a severe inflammation of the brain. Despite being administered to the public for several years, health authorities eventually recommended discontinuing this hazardous formulation.

“Pneumonia is a consistent and prominent finding. Fever is severe and persistent and the degree of headache, when present, suggests a central nervous system involvement. Indeed one patient in our series who was examined by EEG, evidence of disturbed electrical activity of the brain was found, suggestive of encephalopathy… These untoward results of inactivated measles virus immunization was unanticipated. The fact that they have occurred should impose a restriction on the use of inactivated measles virus vaccine. We now recommend that inactivated measles virus vaccine should no longer be administered.”[1]

One of the issues encountered was atypical measles, a condition that emerged in individuals who had received the inactivated measles vaccine. This severe and prolonged illness was marked by high fever, unusual skin lesions, and severe pneumonitis, often accompanied by hemorrhagic rashes, nodular lung lesions, and other systemic symptoms. Cases were reported for up to 16 years after vaccination, and administering the live virus vaccine afterward did not prevent future occurrences, often triggering severe reactions at the injection site.

“Atypical measles was characterized by a higher and more prolonged fever, unusual skin lesions and severe pneumonitis compared to measles in previously unvaccinated persons. The rash was often accompanied by evidence of hemorrhage or vesiculation. The pneumonitis included distinct nodular parenchymal lesions and hilar adenopathy. Abdominal pain, hepatic dysfunction, headache, eosinophilia, pleural effusions and edema were also described. Cases of atypical measles were reported up to 16 years after receipt of the inactivated vaccine. Administration of the live virus vaccine after 2 to 3 doses of killed vaccine did not eliminate subsequent susceptibility to atypical measles and was often associated with severe reactions at the site of live virus inoculation.”[2]

The killed vaccines were swiftly abandoned due to safety concerns. However, the live vaccines also presented significant challenges, as they caused a “modified measles” rash in nearly half of those vaccinated—essentially mimicking an actual measles infection. In fact, 48% of recipients developed a rash, while 83% experienced fevers as high as 106°F. To mitigate these reactions, measles-specific antibodies were administered via immune serum globulin alongside the live vaccine. This approach effectively dulled the otherwise obvious symptoms of fever and rash triggered by the live virus.

“However the vaccine produced a modified measles rash in 48 per cent of the children who received it and fever as high as 106 degrees in 83 per cent of them.”[3]

With the introduction of the newly refined live measles vaccine, hailed as the most effective yet in minimizing side effects, bold claims emerged. Public health officials touted the vaccine as a one-shot solution that provided lifelong immunity without serious adverse reactions. Optimism ran high, with the U.S. Public Health Service predicting the complete eradication of measles by the end of 1967. Dr. Robert J. Warren of the Communicable Disease Center asserted that vaccinating the “right” two to four million susceptible children out of the remaining 12 million could effectively wipe out the disease. However, these promises would later prove to be unfounded.

“The United States Public Health Service licensed a new, refined, live-measles vaccine. Although several live vaccines have been licensed since 1963—all of them one-shot treatments that give life immunity without serious side-effects—the new one is considered by epidemiologists as ‘the best so far in minimizing the side-effects.’”[4]

“Effective use of these vaccines during the coming winter and spring should insure the eradication of measles from the United States in 1967.” [5]

“Measles, the “harmless” childhood disease that can kill, will be nearly eradicated from most areas of the country a year from now, officials of the United States Public Health Service predict… Although there are still more than 12 million susceptible children, vaccination of the “right” two million to four million youngsters could wipe out the disease, according to Dr. Robert J. Warren of the Communicable Disease Center in Atlanta.”[6]

Given these numerous missteps and mishaps, one must pause and ask: What exactly was the problem they sought to solve? Was measles truly a deadly plague, leaving a trail of death and disability across the modern world? To find clarity, let’s first examine the mortality statistics from 1962—the year before the introduction of the killed virus vaccine that would later have to be removed from public use.

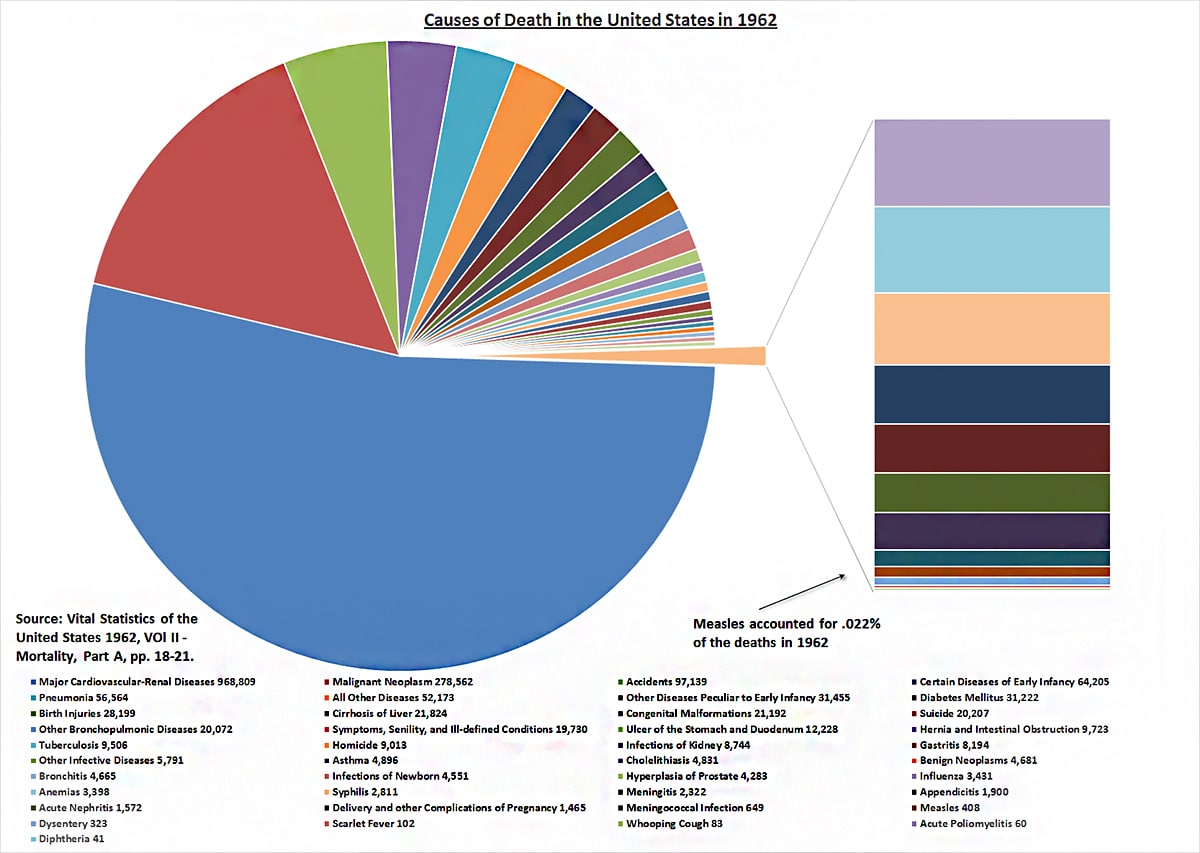

Causes of Death in the United States in 1962 — Vital Statistics of the United States, Vol II – Mortality, Part A, pp. 18-21.

Looking at the causes of death that year, we find that several diseases classified as infectious played a notable role. Tuberculosis claimed 9,506 lives, syphilis accounted for 2,811 deaths, scarlet fever took 102, while broader categories like “other infectious diseases” resulted in 5,791 fatalities and “infections of newborns” caused 4,551 deaths. Still more significant were other problems in childhood, “certain diseases of early infancy” at 64,205, and “other diseases peculiar to early infancy” at 31,455.

Yet, despite the heightened focus on measles, a relatively small 408 measles-related deaths were recorded that year, accounting for a mere 0.022% of total deaths. This places measles near the bottom of the list, prompting us to question whether it genuinely posed the major societal threat often portrayed today. A closer look at historical perspectives from various medical journals sheds light on the matter.

“In the majority of children the whole episode has been well and truly over in a week . . . In this practice measles is considered as a relatively mild and inevitable childhood ailment that is best encountered any time from 3 to 7 years of age. Over the past 10 years there have been few serious complications at any age, and all children have made complete recoveries. As a result of this reasoning no special attempts have been made at prevention even in young infants in whom the disease has not been found to be especially serious.”[7]

“In the United Kingdom and in many other countries, whooping cough (and measles) are no longer important causes of death or severe illness except in a small minority of infants who are usually otherwise disadvantaged. In these circumstances, I cannot see how it is justifiable to promote mass vaccination of children everywhere against diseases which are generally mild, which confer lasting immunity, and which most children escape or overcome easily without being vaccinated.”[8]

These reflections raise an important question: Was measles’s intense fear and widespread notoriety merely a result of the vaccine’s development, rather than a true reflection of its impact on public health?

Still, one could argue that if something can be done to save lives, why not do it?

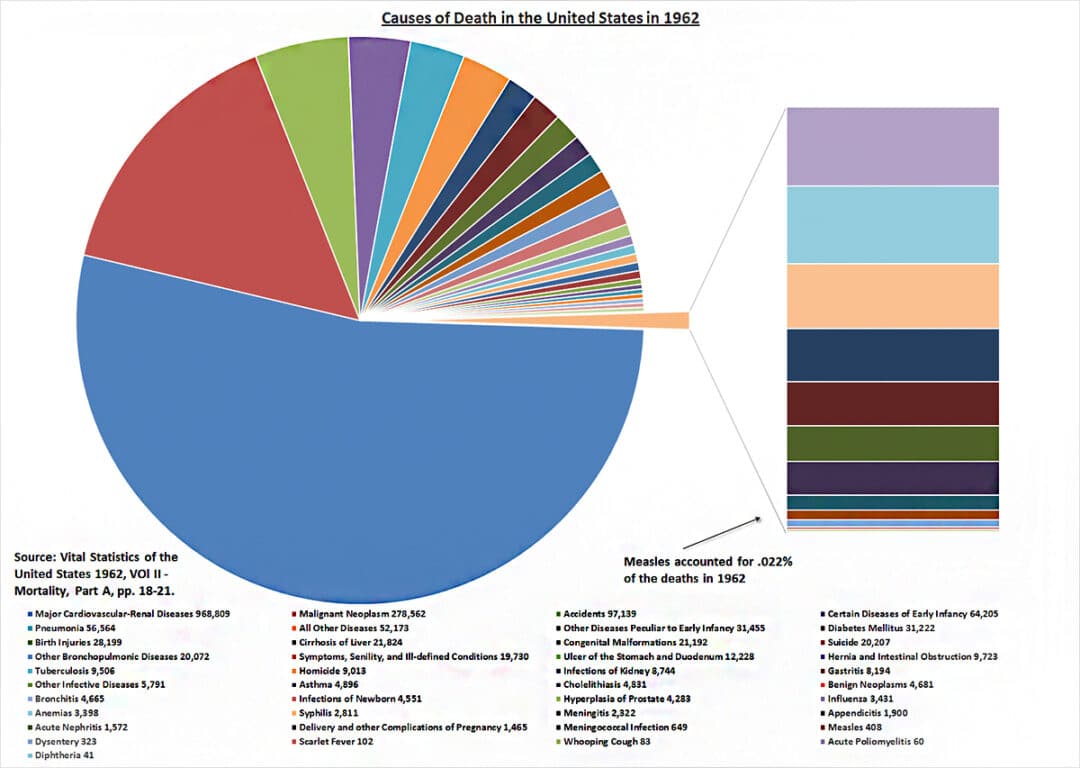

For instance, this social media post highlights a significant decrease in deaths following the vaccine’s introduction. However, the chart in question is deeply flawed:

1. The chart begins in 1939.

2. It is presented in a logarithmic format.

3. It only considers U.S. data.

4. It fails to show the broader trend of declining deaths.

Social media post on measles

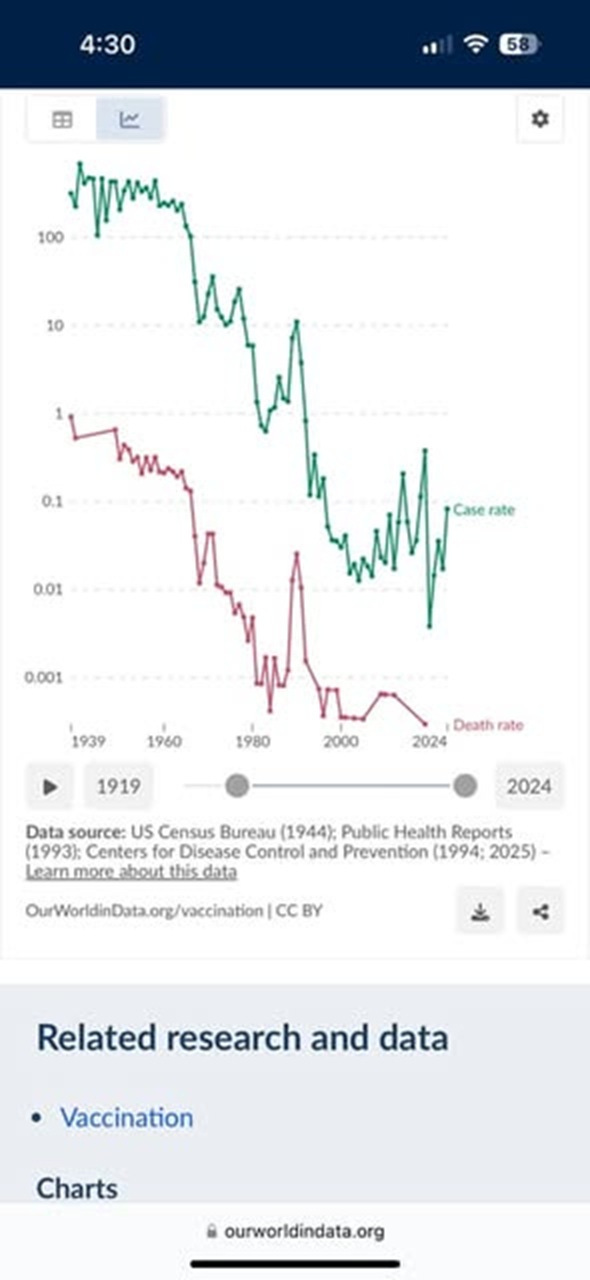

1. If we examine the full range of data available, we see that mortality rates had already plummeted before 1963, when the flawed “killed” vaccine was introduced. The most dramatic improvements occurred before 1939 and continued steadily until 1963.

United States measles mortality rate from 1900 to 1987.

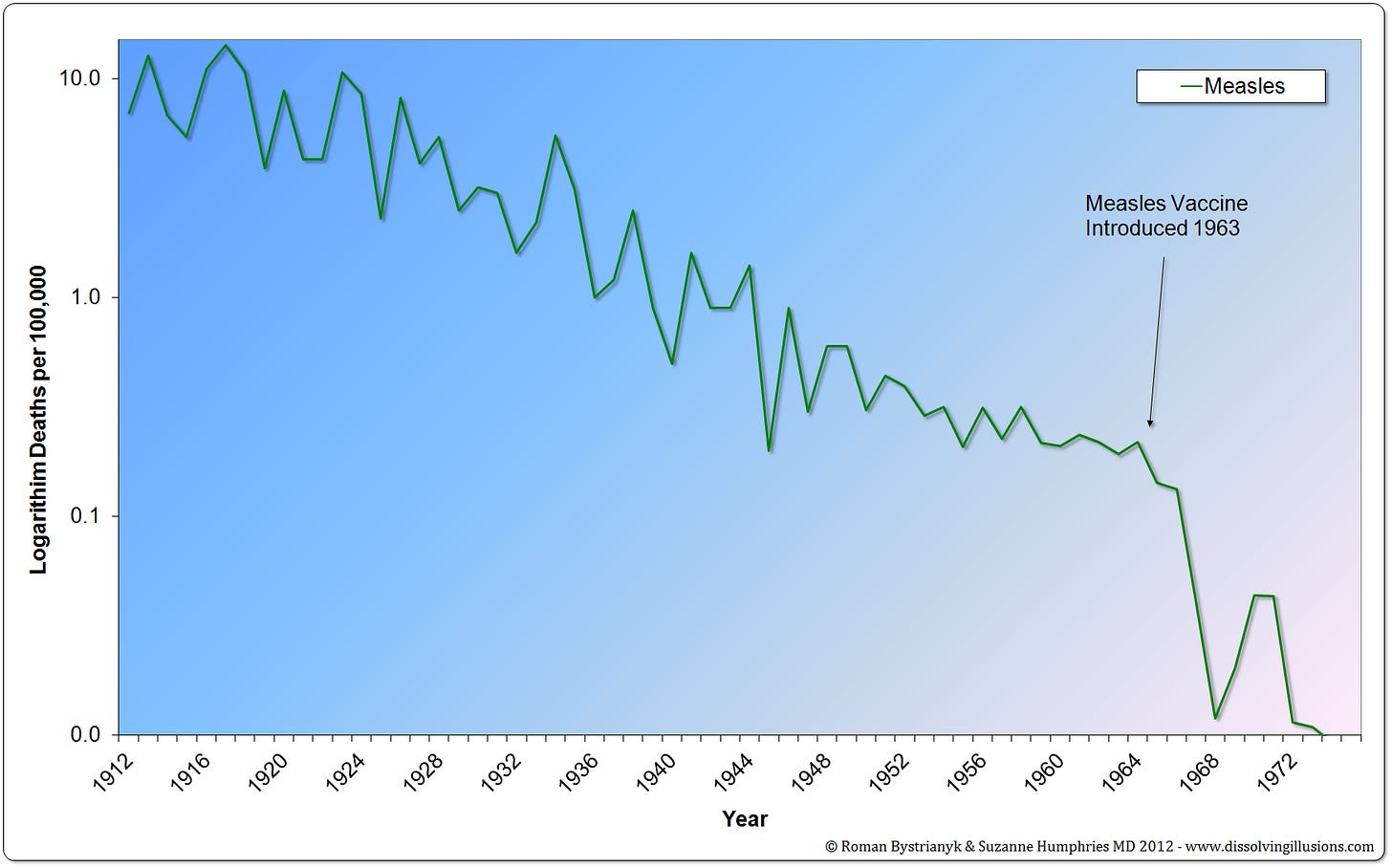

2. The log format used in the social media post exaggerates the post-1963 drop. In Dissolving Illusions, we analyzed a 1980 paper from the American Journal of Public Health, where the authors claimed:

“Death rates due to measles have paralleled measles case rates and have shown a striking decline since the licensure of measles vaccine in 1963.”[9]

However, their graph was presented logarithmically, magnifying the slight decline in deaths after 1963.

United States measles mortality rate from 1912 to 1975 on a logarithm plot.

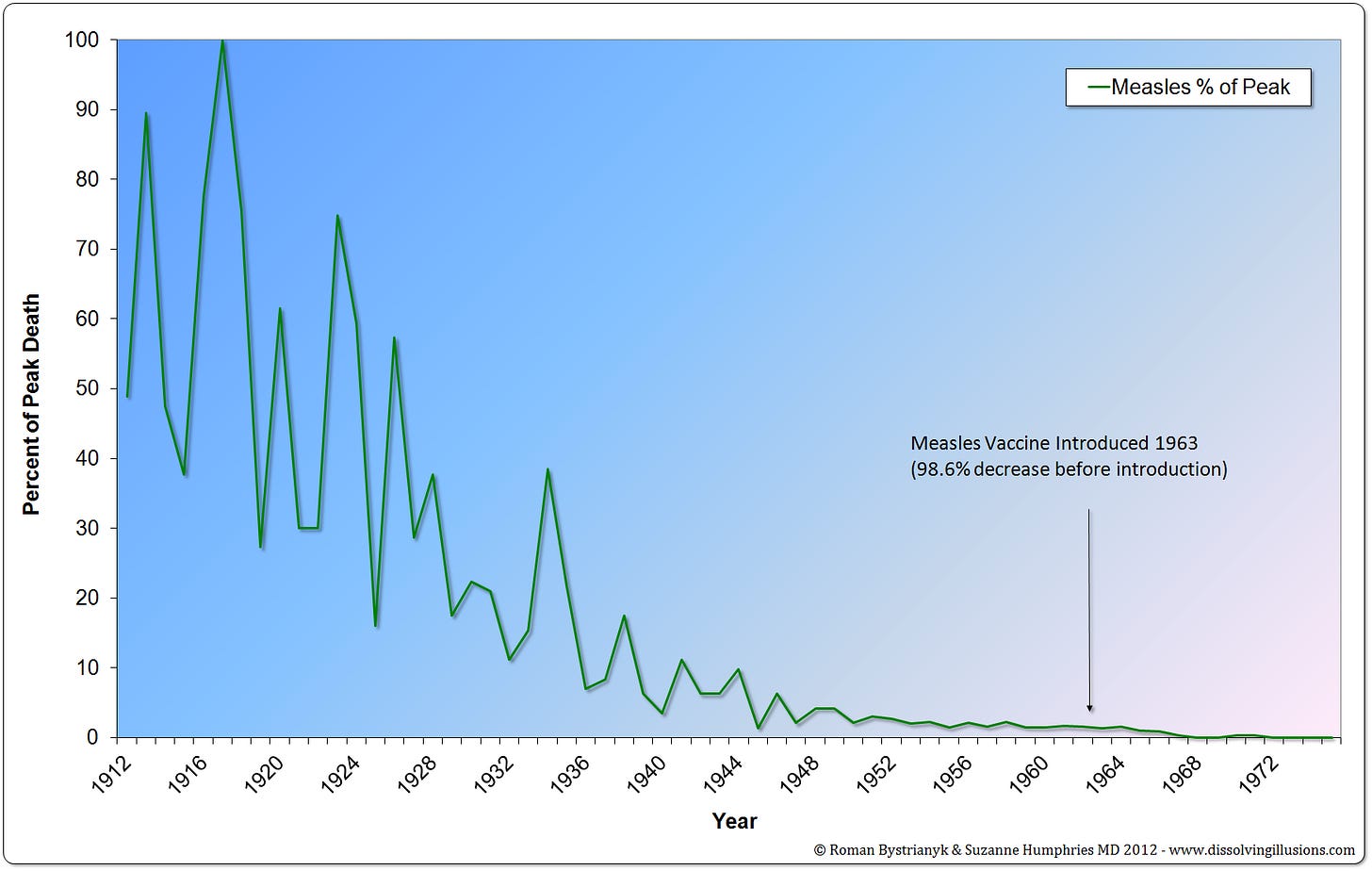

In contrast, when we graph the percent decline from peak deaths using the same data, we find that over 98% of the reduction occurred before 1963.

United States measles mortality rate from 1912 to 1975 in percent from the peak.

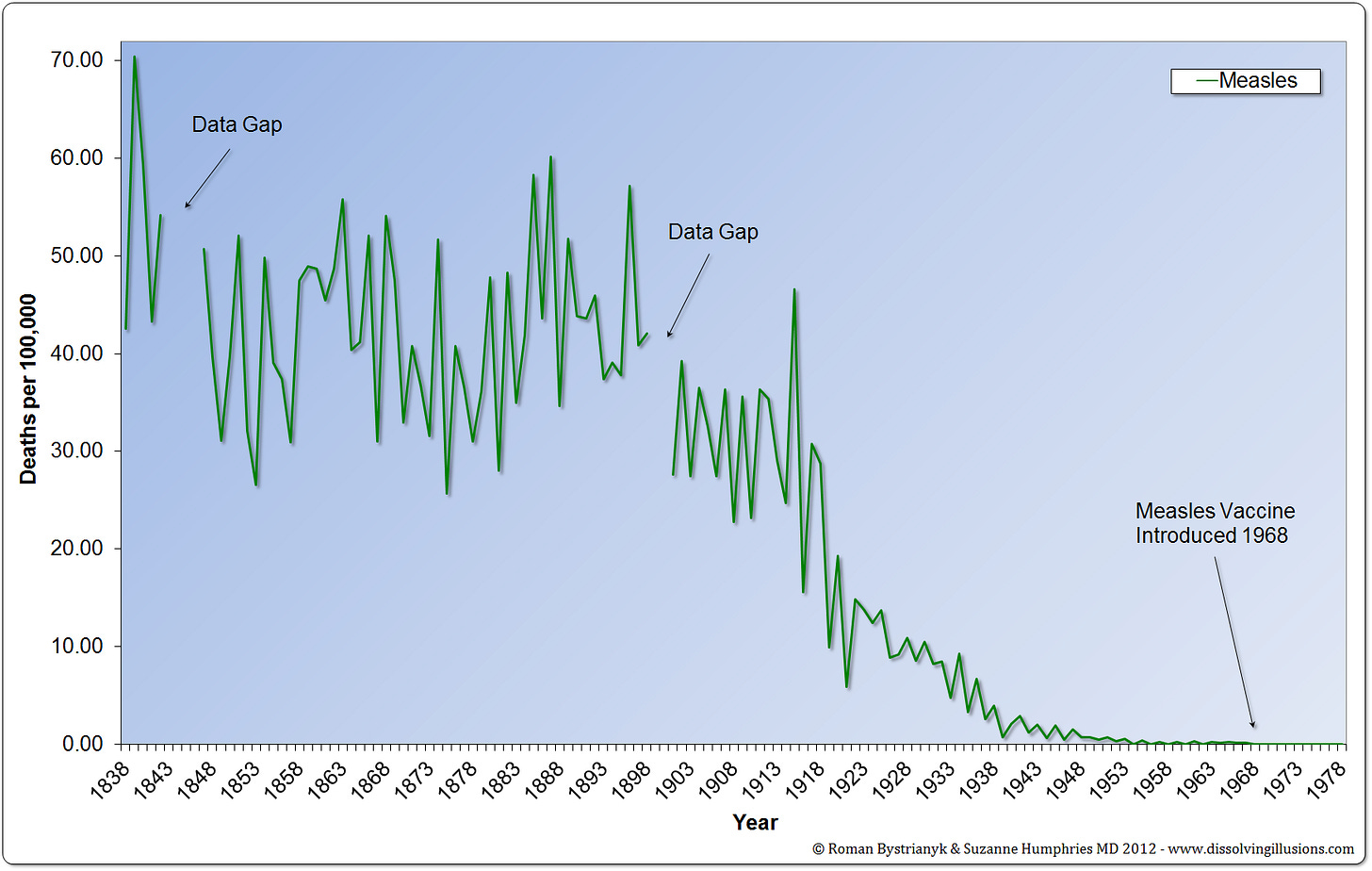

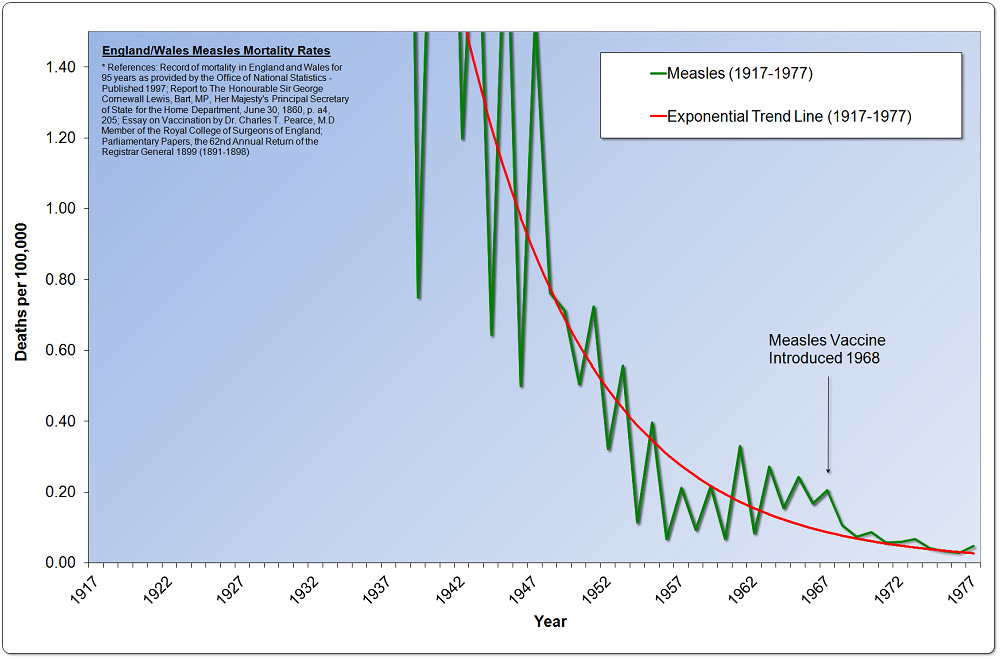

3. Moreover, data from England & Wales, which began collecting statistics in 1838—62 years earlier than the U.S.—reveal an even more striking decline in measles deaths, approaching nearly 100%.

England and Wales measles mortality rate from 1838 to 1978.

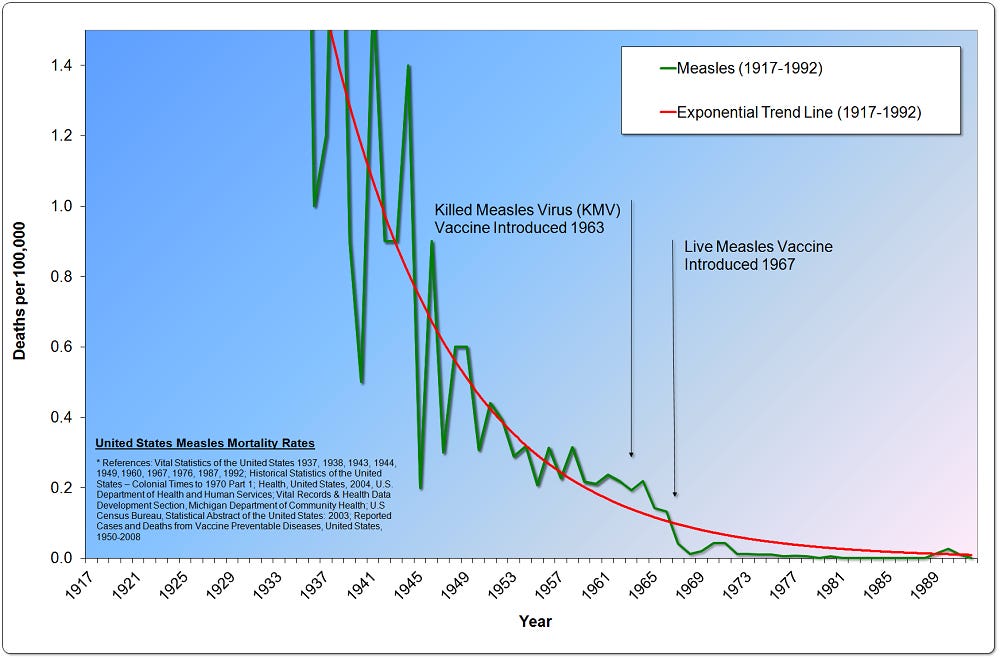

4. When examining trend lines for the U.S., we see minimal post-vaccine improvement. Similarly, for England & Wales, the change is barely perceptible, with adjustments at a scale of 0.1 per 100,000 or 1 in a million.

United States measles mortality rate from 1917 to 1992.

United States measles mortality rate from 1917 to 1992.

The historical narrative surrounding measles vaccination is complex and nuanced. The fear of infectious disease, deeply ingrained in human consciousness, has driven efforts to combat these ailments through medical innovation. However, as the data and historical accounts reveal, the decline in measles mortality preceded the vaccine’s introduction by several decades. This raises critical questions about the necessity and efficacy of mass vaccination campaigns.

The early inactivated measles vaccine, while intended to protect the public, resulted in severe adverse effects, including pneumonia, encephalopathy, and atypical measles. The live virus vaccine, although an improvement, still led to significant reactions, such as high fevers and rashes, necessitating the use of immune serum globulin to mitigate symptoms. Public health officials’ bold predictions of eradicating measles by 1967 ultimately proved unfounded, highlighting the limitations of these early vaccination efforts.

Statistical data further challenge the narrative that vaccines were solely responsible for the dramatic decline in measles mortality. By 1962, the year before the vaccine’s introduction, deaths from measles accounted for a mere 0.022% of total deaths in the United States. The most substantial reductions in mortality occurred long before vaccination efforts began, as improved sanitation, nutrition, and healthcare infrastructure played pivotal roles in enhancing public health.

“Only a comparatively few years ago the death toll from this group of diseases [Measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and diphtheria—the principal communicable diseases of childhood] was serious, but it has now been reduced to a point where their complete suppression may be expected. The public-health movement is said to be responsible for the reduction in mortality from diarrhea and enteritis, which in 1930 had a rate of 20.4 per 100,000 and in 1940 had dropped to a rate of 4.6. Advances in sanitary science, including the Pasteurization of milk, the better refrigeration of foods, and the purification of water supplies, as well as the general rise in the standard of living, are the main reasons for this improvement.”[10]

Visual evidence from historical mortality charts corroborates this trend. Data from England and Wales, dating back to 1838, show an almost complete decline in measles deaths well before the vaccine’s advent. Similarly, U.S. data reveal that over 98% of the mortality reduction occurred before 1963. The use of logarithmic scales and selective data presentation in some social media posts distorts the perceived impact of vaccination.

In light of these findings, one must critically assess the true threat posed by measles and the role of vaccines in mitigating that threat. It is essential to acknowledge the broader historical context and the multifaceted factors that have driven improvements in public health. By doing so, we can foster a more informed and balanced understanding of disease prevention and medical intervention.

A crucial yet often overlooked revelation from these charts is that the near-total decline in measles deaths occurred before the advent of the vaccine. This undeniable trend points to factors far more influential than medical interventions alone. As we meticulously demonstrate in Dissolving Illusions, the true driving force behind the dramatic reduction in mortality from measles—and indeed, from all infectious diseases: typhoid, typhus, whooping cough, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, enteric fever, tuberculosis—was not the suppression of individual pathogens but the overall health and well-being of society itself. Improved sanitation, nutrition, and living conditions laid the foundation for what stands as the greatest public health revolution in human history—one that has been tragically forgotten in the modern narrative of vaccine triumph.

[1] Vincent A. Fulginiti, MD; Jerry J. Eller, MD; Allan W. Downie, MD; and C. Henry Kempe, MD, “Altered Reactivity to Measles Virus: Atypical Measles in Children Previously Immunized with Inactivated Measles Virus Vaccines,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 202, no. 12, December 18, 1967, p. 1080.

[2] D. Griffin et al., “Measles Vaccines,” Frontiers in Bioscience, vol. 13, January 2008, pp. 1352–1370.

[3] “Measles Vaccine Effective in Test—Injections with Live Virus Protect 100 Per Cent of Children in Epidemics,” New York Times, September 14, 1961.

[4] “Thaler to Hold State Senate Hearing to Find Fastest Way to Expedite Plan,” New York Times, February 24, 1965.

[5] David J. Sencer, MD; H. Bruce Dull, MD; and Alexander D. Langmuir, MD, “Epidemiologic Basis for Eradication of Measles in 1967,” Public Health Reports, vol. 82, no. 3, March 1967, p. 256.

[6] Jane E. Brody, “Measles Will Be Nearly Ended by ’67, U.S. Health Aides Say,” New York Times, May 24, 1966.

[7] Vital Statistics, British Medical Journal, February 7, 1959, p. 381.

[8] “Whooping Cough in Relation to Other Childhood Infections in 1977–9 in the United Kingdom,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 35, 1981, p. 145.

[9] Sister Jeffrey Engelhardt; Neal A. Halsey, MD; Donald L. Eddins; and Alan R. Hinman, MD, “Measles Mortality in the United States 1971–1975,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 70, no. 11, November 1980, pp. 1166–1169.

[10] Handbook of Labor Statistics, 1941 Edition, US Department of Labor, pp. 396–397.

0 Comments