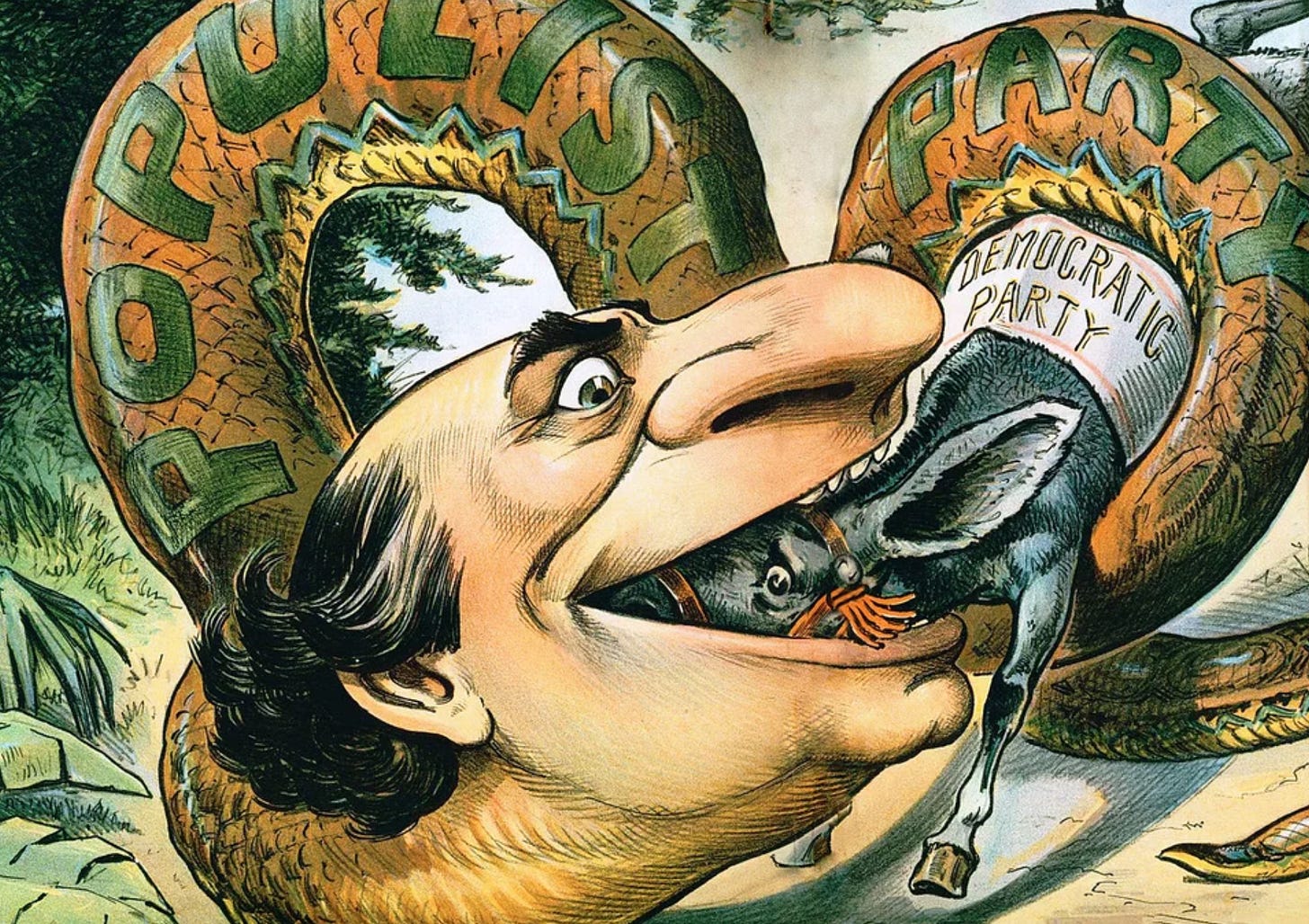

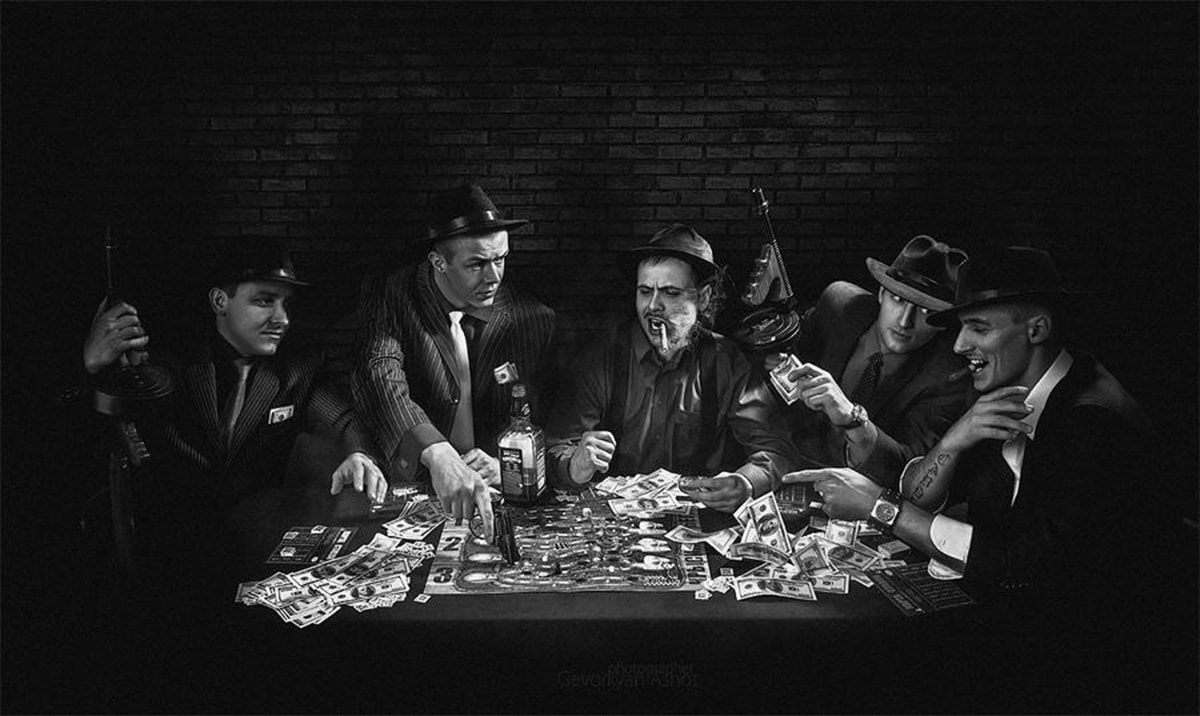

The “Lords of Easy Money,” clockwise from top left: Ben Bernanke prepares his cryogenic journey, Jay Powell accidentally signals five more rate hikes, Alan Greenspan cheered by an ancient memory of refusing a child beggar, Janet Yellen attends Halloween Party as George Washington

The People Versus The Unelected

by Matt Taibbi | Sep, 2022

Review of The Lords of Easy Money, by Christopher Leonard, Simon and Schuster, 384 pages

Click here for Q&A with the author.

In Chicago on July 8, 1896, a former Nebraska congressman named William Jennings Bryan strode onstage at the Democratic National Convention and delivered one of the most famous speeches in American history. A populist and free silver advocate, Jennings stood in opposition to the Wall Street-backed Republican Party, which sought more power for creditors by supporting a gold standard. “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns,” Bryan thundered, to close his address. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

Bryan’s speech can feel inaccessible today because it belonged to an era when “managing the money supply was still in the public realm of democratic action,” as author Christopher Leonard puts it in his remarkable book The Lords of Easy Money. The fights that now take place in the secrecy of the Federal Reserve were then a near-constant concern of congress and a source of bitter conflict between east and west, rich and poor, city-dwellers and farmers. Silver dollars had the de facto impact of increasing the money supply and making farm or prospecting debt easier to repay, while the “organized wealth” Bryan opposed sought a gold standard to keep returns on those loans high. The “Cross of Gold” speech came just after a Great Financial Panic in 1893, and though he would lose to William McKinley, Bryan set the terms for generations of controversies about who got to control the levers of finance.

On May 15, 2010, at a similar juncture a few years removed from a financial crash, a little-known Federal Reserve Bank president from Kansas City named Thomas Hoenig gave a controversial interview to the Wall Street Journal, called “The Fed’s Monetary Dissident.” Hoenig spoke as the economy was pulling out of the 2008 emergency, and as a voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee or FOMC, which helps set interest rates, he took the rare step of publicly disagreeing with peers. “We’ve gotten through the crisis,” he said. “We ought to be thinking about the long run.” Hoenig violated an unspoken taboo, reminding readers that the Fed’s work isn’t just a technocratic process, but “also an allocative policy,” i.e. one that helped pick society’s economic winners and losers — the stuff of politics.

Under the leadership of its soft-spoken, bearded, nebbishy new chairman Ben Bernanke, the central bank had just undertaken the financial equivalent of a Normandy invasion in response to the 2008 crash, adding $1.2 trillion to the money supply in two years, or more than it had in total in every year between 1913 and 2008. Hoenig was concerned because instead of taking early signs of recovery as a chance to pull back, Bernanke was pouring more troops into theater, flooding the economy with money with plans to keep borrowing rates at or near zero for “an extended period” (it would turn out to be ten years). Hoenig worried the Fed was addicting Wall Street to cheap cash, upsetting the delicate balance of financial power he’d spent a life trying to maintain. “I can’t guarantee the carpenter down the street a margin,” he said. “I really don’t think we should be guaranteeing Wall Street… by guaranteeing them a zero or near zero interest rate environment.”

Hoenig’s clipped remarks didn’t land with the fanfare of Bryan’s grandiloquent oratory. In fact, it’s hard to imagine two men with less in common, stylistically. Hoenig was and is a reserved former soldier and number-cruncher who disdained limelight and believed in economy in all things, including words, while Bryan was a man born for the soapbox. Moreover, in a misdiagnosis that that persists to this day, Hoenig’s remarks were criticized as the tightwad meanderings of a hard-money reactionary, an impression that grew stronger when “The Fed’s dissident” was lionized in congressional hearings by the likes of “End the Fed” campaigner and gold-standard advocate Ron Paul. If Bryan wanted to loosen the money supply, and Hoenig wanted to rein it in, what linked them? What could American history’s prototype populist possibly share with a fusty economic traditionalist like Hoenig?

In fact there were similarities. Hoenig’s critics tended to see things backwards, pegging beliefs of his we’d now recognize as economic populism as conservatism, and more importantly mis-labeling the bank-friendly, trickle-down policies of Bernanke as liberal progressivism. This radical switcheroo, turning traditional perceptions of liberalism and conservatism on their head, soon spread to non-financial arenas, as elite officials pitched themselves as progressives, deriding opponents as conspiracist reactionaries. Hoenig is essentially patient zero of this phenomenon, and his story is explained brilliantly in The Lords of Easy Money, in my mind the first book that makes the inner workings of the Fed truly accessible to ordinary readers.

Leonard gets particularly high marks because the Fed — whose officials always used dullness and inscrutability to deflect public scrutiny — is nearly impossible to make interesting and understandable. Leonard pulls it off. A neophyte will come away from The Lords of Easy Money understanding the mechanics of money creation, and the bank’s awesome influence in widening the wealth gap and driving political divisions.

Leonard was a business journalist of repute before, having published at The Washington Post and Fortune and written well-received books about the food business (The Meat Racket) and Koch Industries (Kochland). But sometimes a writer is struck like a thunderbolt by just the right subject at just the right time, and this seems to have happened to Leonard with the Fed. He tells his story through his tremendous source Hoenig, who provides the reader with a tour of the Federal Reserve bureaucracy that’s as clear as a glass-bottomed boat ride. Sometimes also history takes a turn before publication that gives a book a chance to be iconic in its timeliness, and here, too, Hoenig’s post-2008 warnings unfortunately look more prophetic by the minute.

Generations of news consumers had been trained to think the Fed’s decisions to raise or lower interest rates as a narrowly construed, mechanical process. When inflation was high, officials like the famed Paul Volcker raised rates. When inflation was low, and/or the economy needed a boost, wise officials like Alan Greenspan lowered them. We were told this was all we needed to know.

Greenspan in particular was instrumental in designing an intellectual cloaking device called “Fedspeak,” speaking in a language as inaccessible to ordinary people as Klingon, while reinforcing a myth that the Fed’s business was difficult, technical, and apolitical. “Any average citizens who heard snippets of Greenspan’s comments,” Leonard quips, “couldn’t be blamed if they came to believe that whatever the Fed was doing, it must be so complex that no normal human could dare to talk about it, let alone criticize it.” Leonard cites a hilarious example of Greenspan’s peculiar brand of non-English, from congressional testimony:

The fact that economic performance strengthened as inflation subsided should not have been surprising, given that risk premiums and economic disincentives to invest in productive capital diminish as product prices become more stable. But the extent to which strong growth and high resource utilization have been joined with low inflation over an extended period is nevertheless extraordinary…

While at least some Americans could wrap their heads around price inflation, i.e. the idea that the prices of bread or gasoline could rise as banks introduced more money into the system, they knew little (and were encouraged to know little) about the parallel issue of asset inflation. Hoenig, who rose as a bank examiner in the Kansas City Fed, saw how Fed policy created deadly asset bubbles, inexorably herding banks, farmers, and oil producers alike toward cycles of economic ruin.

When the Fed kept money “too cheap for too long,” as Leonard put it, it forced the hands of everyone in a business ecosystem. Leonard explains what Hoenig saw happen to farmers when the Federal Open Market Committee — essentially, the closed society of Fed officials who set rates — kept the price of money down:

When the FOMC kept interest rates low, it encouraged farmers to take on more cheap debt and buy more land. This, in turn, stoked demand for farmland, which pushed up land prices. The higher land prices encouraged more people to borrow and buy yet more land. The bankers’ logic followed a similar path. The bankers saw farmland as collateral on the loans, and they believed the collateral would only rise in value. More lending led to more buying, which led to higher prices, which led to more lending.

For a period of his career, Hoenig had a job comparable to cops or soldiers who make death notifications to families, or to the infamous “Turk” who roams the halls of NFL stadiums on cut-down day. When an enterprise was no longer considered viable enough to be eligible for emergency loans under the Fed’s discount window, Hoenig would have to travel in person to deliver the bad news to company leaders, news that often meant the deaths of companies and by extension, sometimes, the communities who depended upon their jobs. The business leaders often took the news badly. “You could empathize,” Hoenig said. “Lives were destroyed.”

Hoenig seemed suited for this unpleasant duty, but along the way he began to be troubled by some of the underlying dynamics. For instance, he was charged with breaking the bad news to Penn Square, an Oklahoma-based bank that over-extended itself by making reams of risky loans to energy producers on the premise that oil prices would rise indefinitely. The bank of course was at fault, but an not-entirely-illogical answer was beginning to come back:

Tom Hoenig had the duty of breaking the news to Penn Square. The bankers’ response fit the pattern that Hoenig had grown accustomed to. “They would say: ‘It’s your fault that we’re failing. If you gave us more time we could work out of this,” he recalled.

It was getting harder to ignore the argument that by causing asset prices to rise, the Fed’s easy money essentially compelled farmers to buy more land, or banks to invest in risky oil wells. Worse, once the Fed itself was caught in the cycle, it felt more and more pressure to keep the firehose on full blast. Once bubbles begin to inflate, and the prices of farmland or oil wells or internet stocks or residential housing or really anything at all begin to ascend, the slightest downturn in the available credit would send the edifice crumbling.

Now, proximity to the Fed’s money supply became a determining factor in survival. Big banks choked with systemic risk either had to become too big to fail or be permitted to “drink themselves sober” after crashes with cheap Fed financing, as Greenspan biographer William Fleckenstein once put it. But individual savers, smaller firms and ex-factory towns ruined by burst bubbles don’t recover.

This dynamic caused a cataclysm in 2008, the ultimate example of an asset bubble. Easy money massively inflated the value of mortgage securities, and storied companies like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers went all-in on catastrophic bets on ascending home values. The crash ironically was accelerated by a panicked Fed reaction to the bubble, in which Bernanke (who had just replaced Greenspan as chair) abruptly hiked rates to nearly 5 percent in the spring of 2006, sending housing prices plummeting. Hoenig opposed this sudden slamming on of the brakes — the pattern of Fed officials first accelerating too fast and later slamming the money faucet off too suddenly is consistent through the present moment — but the damage had been done. Full meltdown ensued in September of 2008, threatening to grind the entire global financial system to a halt. Subsequent bailout efforts revealed a major change in American governance.

Specifically, the Fed had replaced congress and the White House as the main driver of economic policy, being able to act more quickly and in greater volume in a crisis than the old fiscal authorities. Conservative movements like the Tea Party that focused on “government spending” and Treasury-led bailouts like the TARP program were really looking in the wrong place, as the Fed was executing much huger relief programs essentially in secret. When Barack Obama was elected and made former New York Fed chief Tim Geithner his Treasury Secretary, it guaranteed absolute continuity with these less heralded bailout schemes Geithner had begun at the end of the Bush presidency. As Leonard notes, these policies had a specific aim:

Geithner’s approach to the crisis embodied the modern Democratic Party’s theory of bank regulation. The top priority was to protect the financial stability of banks rather than to close them down or restructure them as FDR had done during the Great Depression.

This was a nuclear-powered version of the trickle-down economics liberals had panned in the Reagan years. The bailouts were designed to prioritize recapitalizing the same financial sector that had just overinflated history’s hugest bubble, on the theory that this would unfreeze a panicked lending environment and create jobs. However, only half of that plan panned out. Though banks were back making monster profits in under a year — Goldman, Sachs doubled projections with a $1.7 billion profit in the first quarter of 2009, less than six months after needing an emergency application for lifesaving cash from the Fed’s discount window to survive — unemployment stayed high, surging to 9.8% by the close of 2010. This set the stage for another unprecedented intervention called Quantitative Easing. This Bernanke-led program would add roughly $4 trillion to the money supply, at the time the largest economic stimulus program in history.

QE was sold to the public as a measure to “rescue the economy,” and the mainstream press framed Bernanke’s actions as the work of a man who was willing to spend what it took to put ordinary people back to work. Leonard describes how Scott Pelley at 60 Minutes depicted Bernanke as a man of the people, showing him hanging out at a drugstore in his home town of Dillon, South Carolina. “I come from Main Street,’“ he said. “This is my background.”

This propaganda belied a profound, ugly truth about both QE and the ten years of zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) Bernanke used to pump the finance sector full of money: it didn’t work. Whether by accident or design, ZIRP and QE — which were premised on the highly dubious belief that creating a “wealth effect” in the upper ranks of society would bleed downward — not only incentivized extreme risk-taking and punished ordinary savers, but more importantly provided direct incentive to hoard money rather than create jobs. In a key passage, Leonard describes the frank admission of a major business leader, as told to Dallas Fed chief Richard Fisher:

Fisher said that he had recently spoken with the chief financial officer of Texas Instruments, who explained how the company was managing money in the age of ZIRP. The company had just borrowed $1.5 billion in cheap debt, but it didn’t plan to use the cash to build a factory, invest in research, or hire workers. Instead, the company used the money to buy back shares of its own stock.

This made sense because the stocks paid a dividend of 2.5 percent, while the debt only cost between 0.45 percent and 1.6 percent to borrow. It was a finely played maneuver of financial engineering that increased the company’s debt, drove up its stock price, and gave a handsome reward to shareholders. Fisher drove home the point by relating his conversation with the CFO. “He said—and I have his permission to quote—‘I’m not going to use it to create a single job.’ ”

This was and is the essence of the QE era. Though the Fed was ostensibly trying to combat unemployment and stimulate growth, its post-2008 plan ended up a thinly disguised subsidy for the very wealthy, leaving the bulk of the population to suck eggs. “It was entirely clear to leaders at the Fed,” Leonard notes, “that to achieve the wealth effect, ZIRP must first and foremost benefit the very richest people in the country.” It should have been obvious that a devastating problem was built into a policy whose chief by-product was asset inflation, namely that it only worked for people with assets:

In early 2012, the richest 1 percent of Americans owned about 25 percent of all assets. The bottom half of all Americans owned only 6.5 percent of all assets. When the Fed stoked asset prices, it was helping a vanishingly small group of people at the top.

The economy evolved much as Hoenig and other critics warned it would, committing the Fed to “near-permanent intervention” and widening the wealth gap. As a result, he’d be introduced to the same kind of withering criticism once directed at Bryan.

As the inimitable Thomas Frank wrote about in The People, No, Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech ushered in generations of savage propaganda from “sound money” advocates in Wall Street and Washington. Jennings himself was alternately depicted in magazines as Satan, a bloodthirsty pirate, and a serpent swallowing the Democratic Party itself:

Hoenig didn’t come in for treatment quite so harsh, but was an early witness to a new and vicious style of neo-aristocratic politics. Hoenig was no Bryan, and would likely blanch at being called a populist, but he was suggesting a danger in concentrating so much influence in the hands of banking powers. More than that, he committed the cardinal sin of the new elite religion, publicly suggesting fallibility of the expert class, criticizing the bank’s policies in the Wall Street Journal. In one of the more infuriating passages of the book, Leonard recreates through transcripts the seething bureaucratic cold of a key meeting of the FOMC from November 2, 2010, in which the assembled pseudo-oligarchs blasted Hoenig for this public breach of decorum.

Bernanke spoke in more comprehensible English than his predecessor, but he replaced Greenspan’s inscrutability with a grating false modesty and an off-putting habit of indirectness, often presenting his own dictates as consensus. He started his criticism of Hoenig by saying he wanted to introduce a “squishy” topic: the “tendency for people to take very strong, very inflexible positions on policy matters prior to the meetings at which those decisions will be made.” As if offhandedly, he suggested the group should look at the “protocol for public statements” and see if “a more cooperative solution” to such outbursts could be found.

Member Janet Yellen, then comparatively unknown, heartily agreed with the boss, saying the group’s “external communications” were “damaging our credibility and our reputation.” Hoenig was being introduced to the vibe now standard everywhere from op-ed pages to campuses to the White House briefing room, where unanimity is expected and dissent considered dangerous and a betrayal.

Leonard was finishing his book just as the Fed was embarking on a boffo sequel to Quantitative Easing, obliterating records for monetary intervention by pumping a staggering $4.6 trillion into the economy in response to the Covid disaster. America’s billionaires roughly doubled their net worth across the two years of extreme asset inflation that ensued, cashing in on yet another period of wild yield-chasing in which insiders reaped huge rewards from speculative investments in everything from corporate takeovers to crypto to pre-IPO fundraising for electric air taxis or health and wellness companies fronted by Sammy Hagar. Now the party is ending and Bernanke’s successor Jay Powell is repeating the pattern of suddenly slamming on the brakes after years of reckless stimulus. Once again, the wealth gap widened significantly on the back of aggressive monetary policy, and renters, savers, and the poor are being set up to take the pain in the coming period of belt-tightening.

As famed Secrets of the Temple author Bill Grieder once observed, the Fed’s bureaucratic structure eerily mirrors the Vatican’s, featuring a Pope, a college of cardinals, and a curia in the form of administrative staff, all communicating with the world through smoke signals about the latest divinations of America’s last true national religion, the magical process of money creation. Leonard in his interview describes zeroing in on Hoenig out of pure journalistic instinct, sensing a great story underneath, and he was right. In The Lords of Easy Money he found a story anyone can understand, that of a man cast out by a corrupt church for the crime of trying to bring the religion to the people, while the unelected Bernankes, Powells, and Yellens of the world sought to keep their work shrouded in Latin. Leonard does right by his excellent source by translating this epic story in clear, convincing language, demystifying an infamously impenetrable bureaucracy in the process and helping introduce us to the real political paradigm of our age, the one destined to replace blue versus red — that of insiders versus outsiders.

0 Comments