‘Kids deserve to see COVID-era school closures litigated again and again until there is a full accounting of who was responsible’KAREN DUCEY/GETTY IMAGES

The Recess of Responsibility

In 2018 I had a painfully shy sixth grade student who could not respond to questions such as “When is your birthday?” or “What is your sister’s name?” She knew the answers but struggled to retrieve the words she needed, so she would anxiously say, “I don’t know,” or simply look away. Over the next year and a half, through a great deal of effort and hard work, she gained confidence, learned how to hold a basic conversation, and started to make friends.

The following school year, on March 13, 2020, California’s public schools closed. When she returned in person in April 2021, I found that she had lost most of the social and verbal progress she had made. As she prepared to go to high school she was again struggling to talk to both students and adults and could not answer simple questions. When she did manage to muster up a few words, her voice was muffled by her mask and no one could understand what she was saying.

Another one of my students had consistent attendance in sixth and seventh grades, but in eighth grade stopped attending his online classes entirely. Virtual learning had stripped school of the elements that were compelling to him—socialization, community, and extracurriculars. He ran away from home multiple times and ended up going to juvenile hall.

I had a student with autism who used to draw constantly all over his schoolwork and was the best artist his age I had ever met. During remote learning he stopped drawing and started to spend more time on his phone. Even after he returned to school in person, his mom told me that he was still not drawing; he now exclusively wanted to play video games. I had a student who was homeless and sometimes attended Zoom class from a tent, a student who was removed from her primary guardian’s house due to abuse during lockdown, and multiple students who exhibited signs of depression. Kids told me on a regular basis that they really wanted to see their friends again and asked, “When will we be able to go back to school?” or “When will COVID be over?”

All of my students were children of color in a special education program run by the Oakland Unified School District, and were from some of the poorest zip codes in Oakland, California. School closures permanently altered the trajectory of their lives. In March 2021, one of my former students was fatally shot. From my perspective, there was a chance he might not have been if schools had been open. He needed structure, a sense of purpose, and a place to go every day. Instead, school closures sent him the message that his future and his life did not matter.

I had been advocating for school reopening since the summer of 2020, but this incident confirmed to me that the damage done to some kids was irreparable. There was simply no coming back from it.

While my students were experiencing these significant hardships, schools in most of Europe and in many U.S. states had already successfully reopened. Bars, restaurants, and gyms in California opened in January 2021, and local private schools were offering in-person instruction. Nearby in wealthy Marin County, public schools reopened crucial special education services in May 2020. My students wouldn’t get the chance to be back in school until almost a year later.

Throughout 2020 and 2021, media outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post were publishing pieces on “The racist effects of school reopening during the pandemic – by a teacher,” “Can we stop telling ‘COVID kids’ how little they are learning?” “Does it hurt children to measure pandemic learning loss?” and “Actually wearing a mask can help kids learn.” Today, these outlets regularly publish pieces detailing the damage done by school closures, and they admit that the most vulnerable students incurred the heaviest losses.

When I criticized school closures over two years ago, I had my job and credentials threatened by strangers, lost most of my friends, and was generally treated as morally or intellectually deficient. So it’s difficult to describe the sense of whiplash I feel now seeing the harms caused by closures treated as self-evident by the very individuals and organizations that promoted this policy.

Currently, entire urban school systems are plagued by high rates of chronic absence, dismal test scores, and student violence. Pediatric hospitals are still seeing enormous surges in mental health emergencies and suicidal thoughts. Over a million students have left U.S. public schools and enrollment may continue to decline. The policy of school closures was not a one-year event—it broke the already fragile American public education system and initiated a tailspin of profound and worsening dysfunction among children and adolescents.

Despite this, not a single official or politician responsible has resigned, apologized, or been held accountable in any way. There is also a complete lack of self-reflection among the experts who pushed for this disaster and normalized remote learning. On Nov. 27, 2022, when asked on Face the Nation if we should expect more closures, Dr. Anthony Fauci answered “I don’t know … I’m not sure,” and said that school districts could decide locally based on community transmission levels. In the absence of any accountability, Fauci is still supporting this harmful and unproven approach.

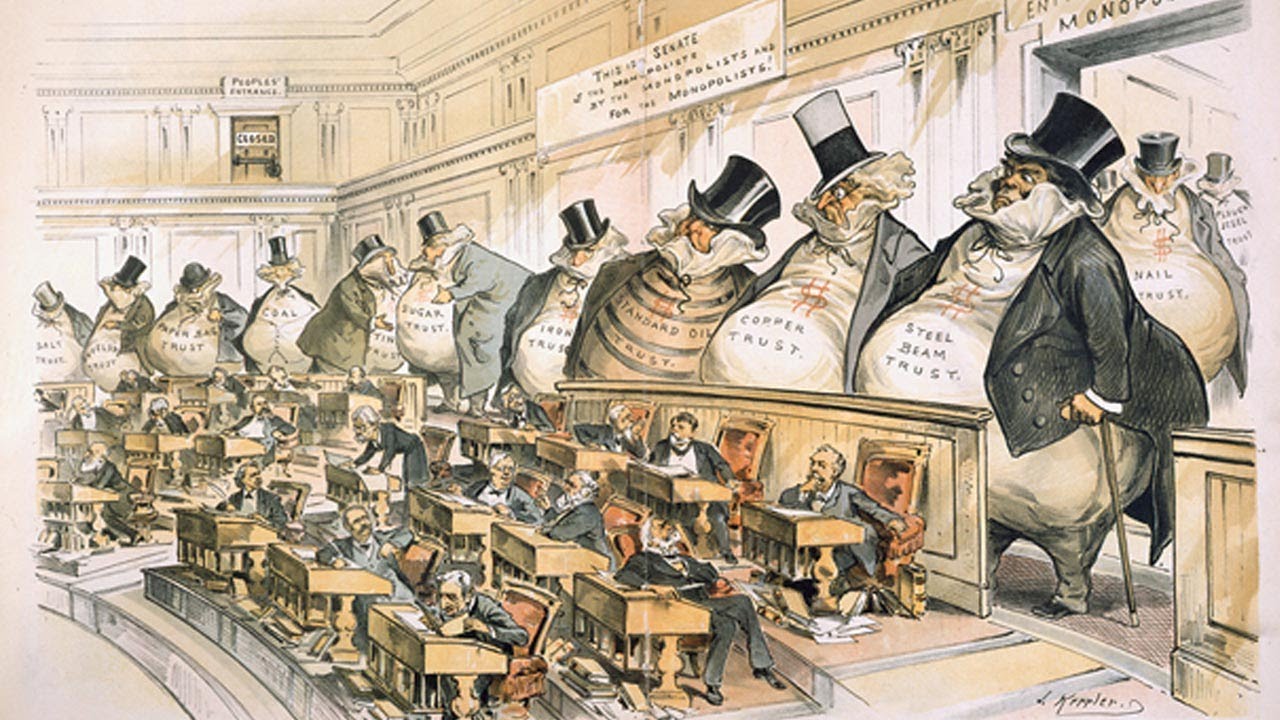

So why, despite all the evidence, have we not seen a true reckoning? When results from the 2022 “Nation’s Report Card,” showed plummeting math and reading scores, some reporters and analysts acknowledged the clear link between school closures and learning loss. Yet others continued to blame “the pandemic” rather than pandemic policies. This is consistent with a general reluctance to assign blame or explain how this happened. NPR education reporter Anya Kamenetz exemplified this tendency in her book The Stolen Year, in which she wrote that her intention was “not to relitigate this mess or point fingers.” But let’s be honest—if school closures could easily be blamed on Trump supporters, white suburban moms, “anti-vaxxers,” or any of the other usual scapegoats, most commentators would be eager to point fingers. The reason they don’t want to do so is because fault actually lies with their own favored groups and institutions: public health experts, academics, Democratic politicians, teachers unions, social justice activists, and journalists themselves.

This refusal to take responsibility or even name those responsible is a way to protect the feelings of adults over the basic rights of children. It is a way to protect victimizers by hiding the truth. The restrictions placed on vulnerable children for two and a half years were akin to institutionalized abuse and emotional torture—kids deserve to see these restrictions litigated again and again until there is a full accounting of what happened to them, why it happened, and who did it.

The refusal to take responsibility is a way to once again protect the feelings of adults over the basic rights of children.

Although elected officials gave the initial school closure orders, these closures had strong popular support in liberal areas for a long time—popular support that stemmed from systematic misinformation and continued as a form of ego preservation. In talking to other teachers in 2020, by far the greatest barrier to discussing reopening was misinformation coming from experts, government agencies, and mainstream news.

In the spring of 2020, for instance, Sweden opened schools for 1.8 million students without masks for three months. At that point Sweden saw zero COVID deaths in children and did not find that teachers were at higher risk than other workers. Unless American teachers engaged in the highly discouraged practice of “doing their own research,” they had almost no way of knowing this. Instead, reporters told us that Sweden (which ended up having one of the lowest COVID mortality rates in Europe) failed, that children were at high risk for mysterious and severe COVID outcomes, and that ending lockdowns was an “experiment in human sacrifice.” As a result, I heard teachers say we couldn’t open schools because “you can’t teach a dead body.”

In July 2020 I wrote an email to leaders in my local union, saying that students with disabilities needed to be back in school. “Distance learning is not feasible and I am willing to teach them in person,” I wrote. “I cannot in good conscience support an effort to withhold services from these students.” The response I received from a leader in the union called the idea of going back “terrifying” and speculated that my students could die or be put on ventilators if I was allowed to teach them. She had a completely fictitious understanding of children’s COVID risks, but it was an understanding that was fully aligned with coverage from CNN, MSNBC, and The New York Times.

Some teachers (such as those claiming to “write wills”) may have been genuinely fearful at first, but their overestimation of risk was not the only factor that kept school closures going. The position of public health experts and teachers unions also stemmed from a desire to oppose Trump, who had voiced support for reopening. One editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine cited the “impending U.S. federal election” as a factor that “limited the ability of public health practitioners to seriously discuss the trade-offs involved in COVID-related decisions” like school closures. In other words, the public health establishment avoided discussing the downsides of COVID restrictions due to the potential political fallout this could create for Democrats.

For this reason, it’s clear that proponents of school closures did not have universally good intentions. What may have started as real concern very quickly became an issue of political arrogance and willful blindness. Multiple studies found that a community’s party affiliation predicted the likelihood of reopening, and many activists simply cared more about “resisting” Trump and virtue signaling than about the welfare of children.

In the summer of 2020, an administrator told me that my district had stopped pursuing reopening plans in part because survey data showed that white parents wanted schools to reopen more than other racial groups. So even though some nonwhite parents did want schools to reopen, school was going to be withheld from all children because white parents wanted reopening the most (and apparently their concerns just didn’t matter). Absurdly, teachers union leaders and academics used this kind of survey data to popularize the idea that the effort to reopen schools was racist even though closures harmed Black and Latino students most, and even though many students in these demographics relied heavily on school for basic services such as meals and health clinics.

A recent poorly controlled study in The New England Journal of Medicine even claimed that mask mandates can decrease “structural racism” in schools. In October 2022, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, a professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, argued in The New Yorker that the debate about learning loss demonstrates an “indifference to Black suffering” caused by COVID. She suggests that school closures were an appropriate measure due to Black parents’ concerns about health and safety. However, it has been made clear by countless available studies from around the world that closures did not have an effect on the incidence of COVID cases or deaths. In the U.S., it was abundantly clear by the fall of 2020 that open schools did not spread COVID, and it was a great injustice that many parents were not made aware of such data. This has been the playbook of academics and experts since 2020: First assume the efficacy of a policy without providing any evidence; then suppress counterevidence and demonize people as “racist,” “right wing,” or “indifferent to suffering” if they question the policy or point out its detrimental effects.

In February 2021, the CDC issued reopening guidelines (written in collaboration with the American Federation of Teachers) that created extensive “safety” barriers and obstacles. This was a way to effectively keep schools closed longer. Currently, however, the concept of “safe reopening” provides cover for Democrats and school closure proponents like the American Federation of Teachers’ President Randi Weingarten, who claims that they always wanted schools to open but were simply making sure the right mitigation measures were in place. To this day, though, the $122 billion in federal money that schools received to fund reopening have gone largely unspent.

Masking, testing, distancing, and quarantine policies were never shown to be more effective than just telling students and staff to stay home when sick. Hygiene theater and the demand for federal funds served little purpose other than to uphold the myth of imminent danger—a myth that, if dispelled, would force teachers and their unions to confront the fact that they severely harmed students. For many teachers in blue states, this is not just a question of admitting error, but of their entire self-image and the need to protect their own psyches. I know that the alternative—facing the fact that your own “team” has done something unforgivable—would be shattering for them.

I know this because I went through this process myself. Before school closures I was a union representative and volunteered for the Bernie Sanders campaign. I did not fit the caricature of the “open schools” advocate: I wasn’t conservative, anti-union, a believer in privatization, or even a parent. I was just a typical public school teacher. Watching my own community needlessly hurt children for more than two years uprooted my entire worldview and sense of identity. So I can understand why somone like Kamenetz, NPR’s education reporter, does not want to point fingers. If she did, she would have to come to terms with what really happened to students: the worst forms of racism, elitism, and ableism all committed by those claiming to stand for “racial and social justice.”

This trend was typified by Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of the United Teachers of Los Angeles, who argued that school reopening would deepen inequities and that “there’s no such thing as learning loss.“

Our kids didn’t lose anything. It’s OK that our babies may not have learned all their times tables. They learned resilience. They learned survival. They learned critical-thinking skills. They know the difference between a riot and a protest. They know the words insurrection and coup.

Myart-Cruz was wrong. Students did not learn “resilience” during school closures. The most vulnerable children in the country learned that school was “not essential” for them, that their affluent peers deserved an education but they did not, that open bars were more important than open classrooms, that fearing disease should be their No. 1 priority in life, and that their suffering was “health.”

Real solutions for this fiasco cannot be enacted without accountability for the perpetrators: Democratic governors, teachers union leaders, and politically motivated news agencies and experts. But blame does not just lie with a few individuals. Many regular people simply went along with something morally reprehensible because they believed their own side to be infallible and because they were too smug to face reality. As a society, we sacrificed the well-being of children for the comfort and ego gratification of adults. The very least we can do now is stop making excuses and be honest about it.

0 Comments