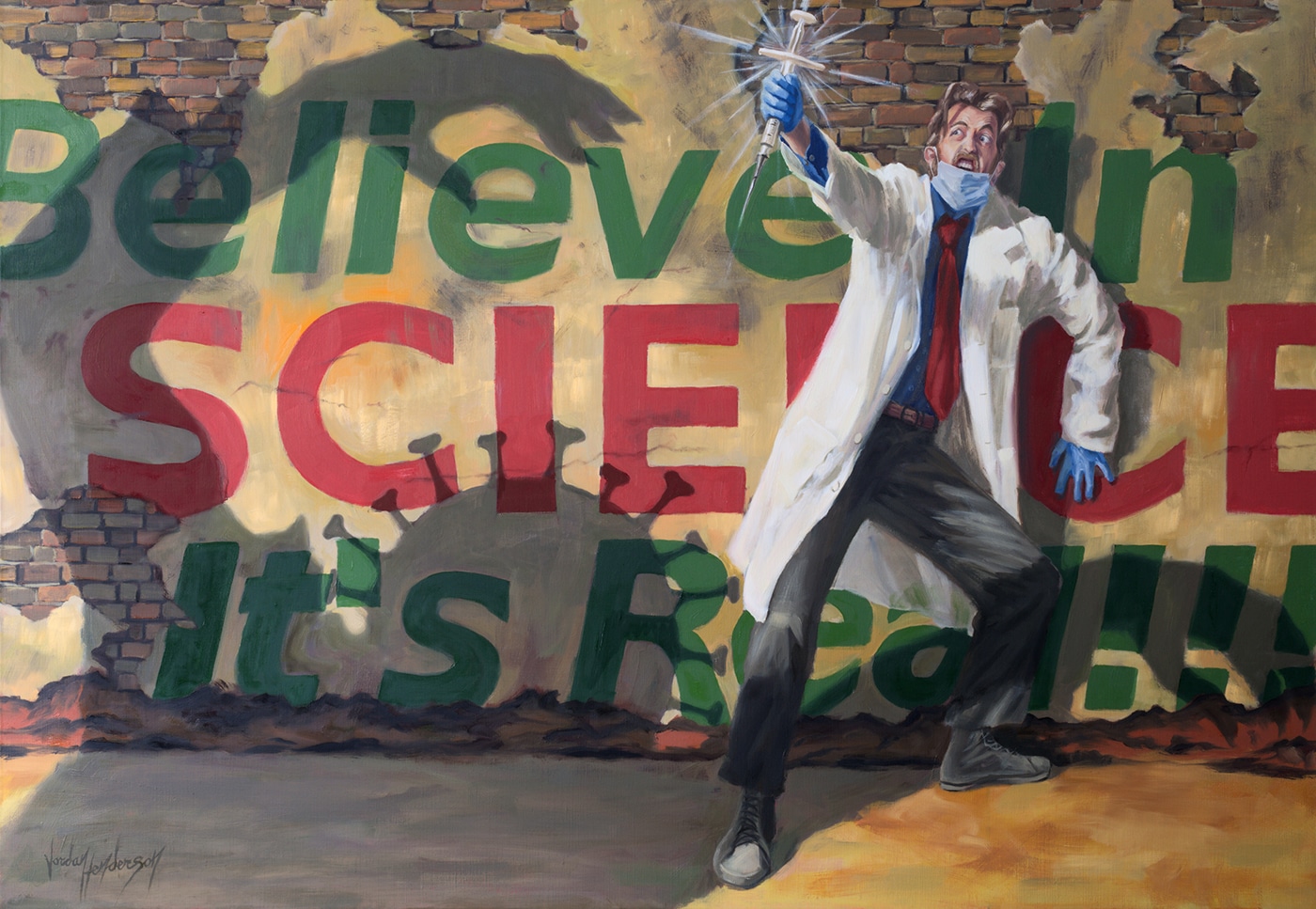

The Virus Cult – A Religion Built on Fear, Not Science

by Unbekoming | Mar 15, 2025

The “Yes Virus” narrative is the most important of them all. It matters more to The Regime than even their beloved climate change story.

Why? Because while most people don’t lose sleep over CO₂ levels they do fear viruses. That fear—the belief in invisible and “infectious” enemies lurking everywhere and in everyone—is the ultimate control mechanism. The ring to rule them all.

And yet, it’s a fiction.

Yes, I too can see the pictures of “viral” particles just like everyone else. But there is no evidence that these particles cause the diseases they’ve been accused of causing.

Cause is the real issue, not whether something exists or can be seen, and cause has most definitely not been proven.

I’ve already reviewed and summarized Mark Gober’s excellent book, The End of Upside Down Medicine, [linked here]. But if you want the most concise, devastating dismantling of the Yes Virus position, look no further than Chapter 2 of that book. It is the best single-source compilation of arguments and scientific challenges to virus theory’s central dogma.

This summary and Q&A are drawn entirely from Chapter 2—with gratitude to Mark Gober.

This Zeck Instagram carousel post is well worth a read.

There’s a rule to my mind, perhaps even a law: if everyone is talking about something, it’s to prevent discussion of something else—something truer.

There are always two stories, but it’s the third story that matters. The first two are designed to keep you from the third.

Consider the Operation Lock Step narrative: The first story was the wet market with its bats and pangolins. The second story was/is the lab leak. Like two well-trained sheepdogs, these two narratives herded collective attention away from the third story: that there was no virus at all. The whole thing was a magical illusion.

Analogy

Imagine a small town where mysterious house fires have been occurring for decades. The town’s fire department has long maintained that the fires are caused by invisible, heat-generating creatures called “pyrobugs” that enter homes through open windows. Nobody has ever actually seen a pyrobug—they’re supposedly too small and quick—but the town has built its entire fire safety system around preventing their entry.

Firefighters claim to have “isolated” pyrobugs by collecting dust from burned houses, mixing it with chemicals and sawdust in a jar, and observing that the mixture sometimes heats up. When the mixture heats, they declare “pyrobugs detected!” They’ve even created “pyrobug detectors” that beep when they sense heat, and distribute “anti-pyrobug spray” to protect homes.

A group of skeptical townsfolk begins asking questions: “If you’ve never isolated a pure pyrobug separate from other materials, how do you know they exist? What if the heating in your jar experiments is caused by the chemicals you’re adding, not invisible bugs?” One skeptic performs an experiment where she creates the same mixture but without any dust from burned houses—and it still heats up.

When skeptics file formal requests asking the fire department to provide evidence of actual pyrobugs—separate from all other materials—officials respond that “pyrobug isolation as defined in your request is not possible in fire science.” Meanwhile, the town continues enforcing strict and costly pyrobug prevention measures, requiring special window screens, mandatory anti-pyrobug spray applications, and quarantining houses where fires occur.

The skeptics aren’t denying that house fires happen—they just suggest the fires might have other explanations: faulty wiring, cooking accidents, or environmental factors. They point out that sometimes multiple houses in the same neighborhood experience fires, not because invisible bugs jumped between them, but because they all used the same defective appliances or were built with the same flammable materials.

This analogy reflects how the No Virus position challenges not just specific claims about particular viruses, but the fundamental concept that invisible, disease-causing viral particles have ever been scientifically proven to exist at all—with profound implications for how we understand disease and implement public health measures.

We are living within that “value” today.

I try to hold my ideas lightly, but I now think that virology is a meta narrative on the scale of climate change, that has been developed for long-term Empire-grade purposes.

We now know that the climate change narrative is a construct. You can read about the primary developer of that narrative here and here.

It is clear that these totalitarian meta narratives can be created, with mountains of money, plenty of co-ordination and planning and above all, time and patience.

Virology has all the hallmarks of a patiently constructed meta narrative. In that context it is far more important, powerful and valuable to Empire than even climate change.

The bio-security state that is now all around us could not exist without virology.

12-point summary

- The “No Virus” Position Fundamentally Challenges Virology: The No Virus position argues that viruses—as defined in modern medical science—do not exist because they have never been properly isolated according to the scientific method. This goes beyond merely questioning if specific viruses cause particular diseases; it challenges whether the microscopic intracellular parasites called “viruses” have ever been proven to exist at all, potentially rendering the entire field of virology a “house of cards.”

- Two Core Methodological Critiques: The No Virus position identifies two primary methodological problems in virology: 1) Viruses are not physically isolated in experiments, meaning no independent variable exists for scientific study, and 2) Virology studies lack proper controls. These issues supposedly render virology a “pseudoscience” that does not follow the scientific method.

- The Gold Standard Method Is Fundamentally Flawed: The 1954 Enders and Peebles study established the cell-culture method that became virology’s gold standard. This involves mixing patient samples with a “soup” of substances and observing cell breakdown. However, the No Virus position argues this method never isolates viruses and the cell breakdown could be caused by the experimental conditions themselves rather than by viruses. Even Enders and Peebles acknowledged their results might be due to “unknown factors.”

- Electron Microscopy Limitations: Electron microscopy, used to “see” viruses, provides only static images of dead material that’s been significantly altered through preparation processes. Researchers have admitted mistaking normal cellular structures for virus particles. The No Virus position argues that without first isolating a virus, scientists cannot know what they’re actually seeing under the microscope, creating a circular identification problem.

- Problems with Viral Genome Sequencing: Without first isolating a virus, genetic sequencing becomes problematic because researchers cannot know whether the genetic material being analyzed comes from a virus or from other cellular debris. The No Virus position argues that SARS-CoV-2’s genome was merely “assembled in silico” (computationally modeled) from genetic fragments of unknown origin, creating an artificial construct rather than mapping a physical entity.

- Government Agencies’ Admissions: Freedom of Information requests to 216 institutions across 40 countries have allegedly failed to produce records demonstrating proper virus isolation. The CDC reportedly stated that “the definition of ‘isolation’ provided in the request is outside of what is possible in virology,” which No Virus advocates interpret as an admission that virology cannot follow the scientific method.

- German Court Victories: The book cites two significant German court cases supporting the No Virus position. Dr. Stefan Lanka won a case after offering 100,000 euros to anyone who could provide scientific evidence of the measles virus, with an expert witness admitting none of the submitted papers had proper controls. In 2023, Marvin Haberland successfully challenged COVID-19 regulations by arguing that virology fails to follow the scientific method.

- Lanka’s Control Experiments: Dr. Lanka conducted experiments reproducing standard virology procedures but without adding patient samples. By simply changing nutrient conditions and antibiotic concentrations, he observed the same cell breakdown (cytopathic effect) that virologists attribute to viruses. This suggests the effects observed in virology experiments may be artifacts of the experimental conditions rather than evidence of viruses.

- Alternative Explanations for Disease: The No Virus position offers multiple alternative explanations for disease patterns typically attributed to viruses, including environmental toxins, EMF exposure, nutritional deficiencies, psychological factors, and seasonal changes. Historical examples like scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra—once thought contagious but later proven to be nutritional deficiencies—demonstrate how easily disease patterns can be misattributed.

- The Changing Definition of “Virus”: The definition of “virus” has changed dramatically throughout history. Originally meaning “poison” or “slimy liquid,” the concept transformed after Watson and Crick’s 1953 DNA discovery, when “overnight a virus was no longer a toxin, but rather a dangerous genetic sequence.” This shift occurred before technology existed that could visualize virus-sized particles, suggesting the field developed based on theoretical assumptions rather than direct observation.

- Antiviral Medications Reinterpreted: The No Virus position reframes “antiviral” drugs as “antimetabolic agents” that interfere with cellular processes rather than targeting viruses specifically. When researchers claim these drugs reduce “viral load,” they’re actually measuring cellular RNA levels while unfoundedly claiming this RNA originates from viruses, when it could be produced endogenously by the cells themselves.

- Sociopolitical Implications: The No Virus position has profound implications for public health policy. If viruses don’t exist as transmissible entities, then lockdowns, mask mandates, and other pandemic measures would be unjustified. Without an “invisible enemy,” future pandemic-based restrictions would be impossible to justify, making this “far more than an intellectual exercise” but a matter with direct relevance to civil liberties and government authority.

40 Questions & Answers

1. What is the “No Virus” position and how does it differ from other perspectives that challenge mainstream viral theory?

The “No Virus” position represents a radical challenge to modern virology, arguing that viruses—as defined in the contemporary scientific framework—do not exist at all. While many dissenters to mainstream medicine might question whether specific viruses cause particular diseases (like those who doubted HIV’s role in causing AIDS), the “No Virus” camp goes much further by asserting that the foundational methodology used to establish the existence of all viruses is fundamentally flawed. They maintain that virologists have never properly isolated virus particles according to the scientific method, and instead work with “soups” of cellular material that they merely assume contain viruses.

This position differs dramatically from other critiques of mainstream medicine that might question treatment protocols, vaccine efficacy, or specific disease mechanisms while still accepting the basic premise that viruses exist. The No Virus advocates argue that the entire field of virology is potentially a “house of cards” built on methodological errors dating back to its founding experiments. The book emphasizes that this isn’t a fringe theory limited to COVID-19 skepticism, but rather a comprehensive critique of virology’s foundations that has gathered significant support, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, with researchers like Drs. Thomas Cowan, Andrew Kaufman, and Stefan Lanka leading a growing movement that challenges the very existence of disease-causing viruses.

2. How does the book define proper virus isolation, and why is this considered a critical issue by the “No Virus” advocates?

Proper virus isolation is defined in the book as physically separating a virus from everything else, similar to how one might take a hammer out of a toolkit and separate it from other tools. Merriam-Webster’s definition is cited: “to set apart from others.” This isolation would require obtaining a purified specimen of the virus by itself, without other cellular material, which could then be photographed with an electron microscope and have its biochemical composition properly analyzed. The book cites Nobel laureate Dr. Luc Montagnier, who stated that the purpose of isolation/purification is “to make sure you have a real virus.”

This issue is considered critical because without proper isolation, scientists cannot establish that a virus exists as an independent entity, let alone determine its properties or effects. The No Virus advocates argue that if a virus hasn’t been isolated first, researchers cannot know if genetic material found in samples comes from a virus or whether effects observed in experiments are caused by a virus rather than by other factors. Without isolation, there is no independent variable that can be scientifically tested. This fundamental methodological problem means that scientists might be attributing disease to hypothetical viruses that have never been proven to exist, potentially misattributing illness to viral causes when environmental factors, toxicity, or other issues could be responsible.

3. What are the two primary methodological problems with virology studies according to the “No Virus” position?

The first fundamental methodological problem identified by the No Virus position is that viruses are not physically isolated in virology experiments. Without true isolation—separating the virus from all other cellular material—scientists cannot establish that viruses exist as independent entities. This lack of isolation means experiments lack an independent variable (the purified virus itself), making it impossible to study a virus scientifically. Instead, researchers use “soups” of cellular material and simply assume viruses are present within them, rather than separating out a virus particle and demonstrating its existence first.

The second core methodological issue is that virology studies lack proper controls. According to the No Virus advocates, this is inherently the case because without first having an independent variable (the isolated virus), proper controls cannot be conducted. The book uses an analogy of determining whether milk makes someone sick—without controlling for other variables like what glass the milk is in, the location where it’s consumed, or the timing relative to meals, simple observation isn’t sufficient to establish causation. The No Virus position maintains that virology experiments fail to eliminate these confounding variables, making it impossible to determine whether observed effects are actually caused by viruses or by other factors in the experimental setup.

4. How has the definition of a virus changed throughout history according to the book?

The book demonstrates that the definition of a virus has undergone substantial evolution over time. Originally, in the first century AD, the Roman writer Celsus used the word “virus” to mean “a slimy poison of visible origin,” drawing from Greek medical writings. This conceptualization of a virus as a poison continued for centuries. The 1940 Medical Dictionary defined a virus as “the specific living principle by which an infectious disease is transmitted,” while Webster’s Dictionary from that era simply referred to a virus as a “slimy or poisonous liquid.” Other mid-20th century sources offered varied and sometimes contradictory definitions.

A pivotal shift occurred following work on bacteriophages (virus-like entities found in bacteria cultures) in the 1940s, which received the 1969 Nobel Prize and became “the basic pattern of reproduction of all viruses.” Watson and Crick’s 1953 discovery of DNA’s double-helix structure further transformed virus theory. As Dr. Lanka puts it in the book: “From that moment on, the causes of disease were thought to be in the genes. The idea of a virus changed, and overnight a virus was no longer a toxin, but rather a dangerous genetic sequence.” The modern definition describes viruses as replicating, protein-coated pieces of genetic material that can supposedly infect living tissues, replicate inside them, damage the tissues when exiting, and transmit to other hosts—a radical departure from earlier concepts.

5. What was the significance of the 1954 Enders and Peebles study in modern virology?

The 1954 study by Thomas Peebles and Nobel laureate John Franklin Enders on the measles virus established what became the gold-standard method for isolating viruses in modern virology, known as the cell-culture method. This approach involves taking fluids from sick patients, mixing them with a “soup” of substances including antibiotics, various animal fluids, and human and monkey kidney cells, then observing whether cells break down (the cytopathic effect). This methodology became the template for virtually all subsequent virus isolation procedures and is still used in contemporary virology.

The timing of this study was particularly significant. Enders won a Nobel Prize in December 1954 for his previous work on polio, which gave tremendous credibility to the measles virus paper published just months earlier in June. As Dr. Lanka notes in the book, “This paper became a scientific fact which was never, ever questioned.” However, the No Virus position argues that this foundational study contained critical flaws that have been perpetuated throughout virology. Importantly, the book points out that Enders and Peebles themselves acknowledged limitations in their paper, stating that “cytopathic effects which superficially resemble those resulting from infection by the measles agents may possibly be induced by other viral agents present in the monkey kidney tissue…or by unknown factors.” Despite these caveats from the authors themselves, their methodology became the unquestioned foundation of modern virology.

6. What are the specific criticisms of the cell culture method used in virology?

The specific criticisms of the cell culture method revolve around its inability to establish causation and isolate a true independent variable. The No Virus position argues that when fluids from sick patients are added to cell cultures and cells break down, researchers cannot determine whether this breakdown is caused by an alleged virus or by other factors. These other factors could include the various cellular materials in the patient samples or even the experimental conditions themselves. The cell cultures contain antibiotics, reduced nutrients, and animal materials that could be toxic to cells and cause them to break down regardless of whether a virus is present.

Dr. Stefan Lanka’s experimental work directly challenges this method, as he demonstrated that cell breakdown (the cytopathic effect) occurred in control experiments where no alleged virus was added—simply by changing the nutrient medium and increasing antibiotic concentration, or by adding yeast RNA. The book argues that the cell culture method suffers from a logical fallacy known as “affirming the consequent”—assuming that if a virus causes cells to break down, then observing cell breakdown proves a virus is present, when many other factors could cause the same effect. Moreover, the method presupposes that what happens in artificial test tube environments accurately represents what occurs in complex living organisms—an assumption the No Virus advocates consider highly questionable for determining real-world disease causation.

7. How do electron microscopy limitations factor into the “No Virus” argument?

Electron microscopy limitations form a crucial component of the No Virus argument, focusing on both technical and interpretative problems. The book explains that electron microscopes only provide static images of dead material, which cannot demonstrate a virus performing all the functions required by its modern definition (entering cells, replicating, damaging tissues, and exiting). Additionally, the sample preparation process significantly alters the material being viewed—samples are embedded in resin, cut into thin slices, or frozen, potentially creating artifacts that don’t exist in living systems.

Furthermore, the No Virus position highlights the problem of misidentification. The book cites articles from Kidney360 and the CDC’s journal Emerging Infectious Diseases acknowledging that researchers have “inaccurately reported subcellular structures, including coated vesicles, multivesicular bodies, and vesiculating rough endoplasmic reticulum, as coronavirus particles.” Dr. Bailey pointedly asks how experts know what a virus looks like if they’ve never properly isolated one first. This circular reasoning is exemplified by the case of coronavirus identification, where particles are identified as viruses based on comparison to template images from previous studies that themselves lacked proper isolation. The No Virus advocates also criticize the lack of control images in electron microscopy studies, arguing that without proper controls, researchers cannot know if the particles they’re seeing would appear regardless of whether a virus was present.

8. What logical fallacy does the book claim is inherent in virology’s experimental conclusions?

The book identifies “affirming the consequent” as the key logical fallacy inherent in virology’s experimental conclusions. This fallacy is formally structured as: “If P, then Q. Q, therefore P.” Applied to virology, this becomes: “If there is a disease-causing virus in a sample, then it causes cells to break down. We observed that cells broke down in the experiment; therefore, there was a virus.” This reasoning is logically invalid because it overlooks the possibility that many other factors could cause the same effect (cell breakdown).

The flaw in this reasoning is central to the No Virus critique of the cell-culture method. When researchers observe cells breaking down after adding patient samples to cell cultures, they conclude a virus must be present. However, this ignores numerous other potential causes of cell breakdown, including the antibiotics, starvation conditions, and toxic decaying proteins in the experimental setup itself. Dr. Lanka explicitly points this out, stating that researchers are “killing those cells, intoxifying them with cytotoxic antibiotics, starving them to death, reducing the nutrition, and of course, adding material proteins which are in decay… when those cells are dying in the test tube, [the experimenters equate] it with the presence of the virus.” The No Virus position maintains that this logical error permeates the entire field of virology, leading scientists to mistakenly attribute cellular changes to hypothetical viruses rather than to the experimental conditions themselves.

9. What admissions did Dr. Luc Montagnier make regarding HIV isolation according to the book?

According to the book, Dr. Luc Montagnier, who won the Nobel Prize for discovering HIV, made the remarkable admission in a 1997 interview that in his original 1983 experiment, “we saw some particles, but they did not have the morphology typical of retroviruses….I repeat, we did not purify.” This statement directly undermines the claim that HIV was properly isolated using the scientific method. The book emphasizes that “the magnitude of this statement should not be underestimated,” as it comes from the very researcher credited with discovering the virus.

Montagnier further elaborated on why he didn’t purify the virus, claiming: “There was so little production of the virus [that] it was impossible to see what might be in a concentrate of the virus from the gradient [‘pure virus’]. There was not enough virus to do that.” The No Virus advocates highlight the contradiction in this reasoning—if there wasn’t enough virus to isolate and study, how could scientists know it was causing disease in humans? This admission from a Nobel laureate is presented as evidence that even at the highest levels of virology research, the fundamental requirement of proper viral isolation has not been met, calling into question whether HIV—and by extension other viruses—exist as described in the scientific literature.

10. What evidence from Freedom of Information requests does the book present to support the “No Virus” position?

The book presents extensive evidence from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests led by biostatistician Christine Massey that appears to support the No Virus position. By June 2023, Massey had obtained responses from 216 different institutions across 40 countries, with none able to provide records demonstrating isolation of SARS-CoV-2 directly from patient samples without mixing them with other genetic material. The most notable response came from the CDC on November 2, 2020, which stated: “A search of our records failed to reveal any documents pertaining to your request” for records describing the isolation of SARS-CoV-2 directly from patient samples.

In a subsequent response dated March 1, 2021, the CDC made an even more remarkable statement: “The definition of ‘isolation’ provided in the request is outside of what is possible in virology.” The No Virus advocates interpret this as an explicit admission that virology does not follow the scientific method, as it cannot isolate an independent variable. The book also describes FOI responses regarding other viruses, with agencies unable to provide isolation records for numerous alleged viruses including Ebola, hepatitis, herpes, HIV, measles, smallpox, and many others. Another telling response came from the UK Health Agency, which cited a “national security” exemption to avoid providing details about control methods used in virus isolation studies, claiming this would “directly contravene an explicit request from the World Health Organization.”

11. What were the outcomes of the German court cases involving Dr. Stefan Lanka and Marvin Haberland?

Dr. Stefan Lanka won a significant legal victory after initially offering 100,000 euros to anyone who could provide scientific evidence that the measles virus exists. When physician David Bardens submitted six papers that allegedly proved the virus’s existence, a lower court ordered Lanka to pay. However, Lanka appealed and ultimately won in 2016, with Germany’s highest court dismissing Bardens’ subsequent appeal. Although skeptics claimed Lanka won on a technicality, the book emphasizes that during the proceedings, Professor Andreas Podbielski from the department of medical microbiology and virology in Rostock admitted that none of the six papers submitted had been done with proper controls, leading Dr. Samantha Bailey to conclude that “the best six papers in the entire measles ‘virus’ literature didn’t follow the scientific method.”

The second German court victory came in April 2023 with engineer Marvin Haberland, who challenged COVID-19 lockdown measures by intentionally violating a mask mandate. His defense strategy focused on Germany’s Law for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in Humans, arguing that since the law required institutions to abide by science (following the scientific method), and virology doesn’t follow this method, the law’s provisions should be considered irrelevant. In a telling development, the judge chose to close Haberland’s case rather than rule on it, which Haberland interpreted as an attempt “to avoid any further damage to virology.” Four others using the same defense strategy had their cases similarly closed, suggesting to No Virus advocates that the courts were unwilling to publicly address foundational problems in virology.

12. What control experiments did Dr. Stefan Lanka conduct, and what were their results?

Dr. Stefan Lanka conducted control experiments in 2021 that directly challenged modern virology’s methodologies. His primary experiment reproduced the standard cell-culture method used in virtually all modern virus isolation studies, but with a critical difference: he never added any fluid from a sick person alleged to contain a virus. Instead, he simply changed the nutrient medium to “minimal nutrient medium” (reducing fetal calf serum from 10% to 1%) and tripled the antibiotic concentration in the cell culture. By day five of the experiment, Lanka observed the characteristic cell breakdown (cytopathic effect) that virologists typically claim proves the existence and pathogenicity of a virus—despite no alleged virus being added to the culture.

In a second trial, Lanka followed the same procedure but added yeast RNA instead of patient fluids, again observing cell breakdown. These results demonstrate that the cell breakdown effects typically attributed to viruses in standard virology experiments can occur without any virus being present, suggesting they are actually artifacts of the experimental conditions themselves. As Dr. Cowan summarizes in the book, these outcomes “can only mean that the [cell breakdown] was a result of the way the culture experiment was done and not from any virus.” While the book notes that more similar experiments and independent replications are needed, Lanka’s initial results provide compelling evidence supporting the No Virus position that standard virology methods produce misleading results that have been misinterpreted as proving viral existence.

13. How does the book explain the existence and effectiveness of “antiviral” drugs if viruses don’t exist?

The book addresses the apparent contradiction of “antiviral” drugs’ existence and effectiveness by reframing their mechanisms of action. According to Dr. Samantha Bailey, these medications don’t actually target viruses at all—they function as “antimetabolic agents” that interfere with cellular processes within the host cells. She compares them to chemotherapy, which doesn’t specifically attack cancer cells but rather disrupts metabolic processes, affecting both healthy and cancerous cells. In essence, the No Virus position maintains that these drugs are misclassified based on an incorrect understanding of their mechanism of action.

When researchers claim that antiviral drugs prevent “viruses” from replicating by measuring reduced nucleic acid levels in test tubes, they’re making an unfounded assumption about the origin of these genetic sequences. Dr. Bailey cites the example of Ivermectin studies on SARS-CoV-2, where researchers reported a “5000-fold reduction in virus” but were actually only measuring cell-culture RNA levels while unfoundedly claiming the RNA came from a virus. The No Virus perspective suggests that these genetic sequences could be produced endogenously (from within the cell) without requiring the existence of any virus. Therefore, the effects of so-called “antiviral” drugs are real but have been fundamentally misinterpreted by mainstream science because they’re working through different mechanisms than those proposed by conventional virology.

14. What alternative explanations for disease does the book offer instead of viral causation?

The book presents a multifactorial understanding of disease causation that focuses on environmental factors rather than contagious viruses. It suggests that people in the same place and time can develop similar symptoms due to shared exposure to toxic substances in food, water, air, medicines, and consumer products. Specific locations might have higher concentrations of toxins, creating clusters of illness that mimic contagion patterns. The book also highlights the role of electromagnetic fields (EMFs), especially prevalent in the wireless era, and discusses how varying electricity exposure might impact health more significantly than commonly acknowledged.

Other factors mentioned include seasonal variations in humidity, temperature, and sunlight exposure; radiation from accidents or deliberate releases; nutritional deficiencies (citing historical examples of scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra that were once thought contagious but were actually caused by vitamin deficiencies); psychological factors including mass fear; and potential government experimentation with aerosols or other unacknowledged projects. The book also raises the possibility of COVID-19 vaccine toxicity contributing to illness. The No Virus position emphasizes that modern allopathic medicine’s germ-focused approach may overlook these significant environmental and internal factors, while acknowledging that the complete explanation for disease patterns might involve elements beyond current scientific understanding, noting that scientists only understand what 4% of the universe is made of.

15. How does the book explain the issue of genetic sequencing of viruses like SARS-CoV-2?

The book fundamentally challenges the validity of viral genetic sequencing by emphasizing the necessity of first isolating a virus before determining its genetic makeup. Without properly isolating a pure virus particle, researchers cannot know whether the genetic material they’re analyzing comes from a hypothetical virus or from other cellular debris in the sample. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 specifically, Dr. Mark Bailey argues that scientists merely “assembled an in silico ‘genome’ from genetic fragments of unknown provenance, found in the crude lung washings of a single ‘case’.”

The term “in silico” is highlighted as particularly problematic—it refers to a computational model or simulation of a genome rather than a physical entity isolated from nature. Dr. Kaufman describes it as an “artificial version of something that doesn’t exist.” Furthermore, the book criticizes the lack of proper controls in the sequencing process, noting that scientists should run the sequencing on various samples, including those without the alleged virus, to validate their findings. The No Virus position maintains that viral “variants” are simply different combinations of genetic fragments compiled by computers that don’t perfectly match the original template genome. Rather than interpreting these as failures to reproduce results, researchers label them as “variants.” This entire approach to viral genomics is characterized as fundamentally flawed because it begins with assumptions about the existence and nature of viruses rather than establishing these through proper scientific methodology.

16. What is the significance of “in silico” genome assembly in the “No Virus” critique?

The concept of “in silico” genome assembly represents a core criticism in the No Virus argument. The book defines it as a computational model of a hypothesized genome that doesn’t exist in its entirety in any actual experiment. Dr. Andrew Kaufman describes it bluntly as “an artificial version of something that doesn’t exist. It is a model or a simulation” that is essentially “man-made.” This computational approach allows scientists to piece together fragments of genetic material found in samples and claim they’ve sequenced a viral genome, despite never having isolated a physical virus particle.

The significance of this critique lies in exposing the gap between what the public believes happens in viral research and what actually occurs. While most people assume scientists have physically isolated viruses and directly sequenced their genomes, the No Virus perspective argues that researchers are actually creating artificial constructs from genetic fragments of unknown origin. Dr. Mark Bailey emphasizes this point regarding SARS-CoV-2, noting that all researchers had was “a 41-year old man with pneumonia and a software-assembled model ‘genome’ made from sequences of unestablished origin found in the man’s lung washings.” This computational modeling approach is presented as a fundamental departure from proper scientific methodology that requires physical isolation of the subject being studied. The in silico approach effectively allows virologists to claim discoveries without ever demonstrating the physical existence of the viruses they purport to study.

17. What specific government agencies have allegedly failed to provide evidence of virus isolation?

The book documents a remarkably extensive list of government agencies worldwide that have allegedly failed to provide evidence of virus isolation in response to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. Most prominently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) responded on November 2, 2020, stating: “A search of our records failed to reveal any documents pertaining to your request” for isolation records of SARS-CoV-2. In a subsequent response, the CDC claimed that the definition of isolation provided in the request was “outside of what is possible in virology,” which No Virus advocates interpret as an admission that virology cannot follow the scientific method.

Other agencies mentioned include New Zealand’s Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR), which stated it “has not performed any experiments to scientifically prove the existence of SARS-CoV-2 virus.” The UK Health Agency cited a “national security” exemption to avoid providing details about control methods, claiming release would “directly contravene an explicit request from the World Health Organization.” The Public Health Agency of Canada also responded that isolation “cannot be completed without the use of another medium.” According to Christine Massey’s FOI campaign, 216 different institutions across 40 countries have failed to provide records demonstrating proper virus isolation, not just for SARS-CoV-2 but also for other alleged viruses including Ebola, measles, HIV, hepatitis, herpes, and many others. This global pattern of agencies being unable to produce isolation records is presented as compelling evidence supporting the No Virus position.

18. How does the book describe the relationship between bacteriophages and virus theory?

The book describes bacteriophages as playing a pivotal role in shaping modern virus theory, despite potentially representing a different phenomenon. According to Dr. Stefan Lanka, contemporary virus concepts were significantly influenced by work on bacteriophages—virus-like entities found in pure bacteria cultures—dating back to the 1940s. This work received the 1969 Nobel Prize in medicine, with the Nobel Prize summary declaring that bacteriophage reproduction is “now generally accepted as the basic pattern of reproduction of all viruses.”

This extrapolation from bacteriophages to human viruses is presented as a critical error in the development of virology. The book suggests that scientists observed processes in bacteriophages and then assumed, without proper verification, that similar processes must occur with alleged human viruses. However, the No Virus position distinguishes between the two, noting that bacteriophages “have been isolated. These could be photographed, isolated as whole particles, and all their components could be biochemically determined and characterized.” In contrast, Lanka asserts this “has never happened with alleged viruses of humans, animals, and plants because these do not exist.” The book also briefly mentions an alternative interpretation of bacteriophages not as agents that “infect” or “eat” bacteria, but as potential “survival mechanisms for bacteria when they are in a stressed situation,” suggesting even bacteriophages might be misunderstood within the conventional framework.

19. What does the book claim about the origins of COVID-19 symptoms if not caused by SARS-CoV-2?

The book presents a multifactorial explanation for COVID-19 symptoms while emphasizing that not having a definitive alternative explanation doesn’t prove viral causation. It suggests that the symptoms associated with COVID-19 might result from any combination of environmental toxins, EMF exposure, radiation, psychological factors like mass fear, nutritional deficiencies, or other unknown causes. The book specifically mentions that the COVID-19 vaccines themselves might be contributing to illness, noting that “most people don’t even know the ingredients of the fluid that was injected into their body, let alone what the impacts on their health might be.”

The explanation is further complicated by data problems, including false-positive test results and misattributed causes of death where “a COVID-19-positive test led to a ‘COVID-19-death’ classification.” The book also points to unexplained anomalies, such as cases where some people in the same location developed COVID-19 symptoms while others didn’t, questioning how this could happen if the virus were highly contagious. While acknowledging that the complete answer might be “beyond our current understanding of science and medicine,” the book suggests that the true explanation for COVID-19 symptoms is likely complex and multifactorial rather than reducible to a single viral cause. It emphasizes that saying “I don’t know” is sometimes more scientifically honest than clinging to an unproven viral explanation.

20. How does the “No Virus” position explain instances of apparent disease contagion?

The No Virus position challenges the conventional understanding of disease contagion by offering alternative explanations for why people in proximity might develop similar symptoms. The book emphasizes that people in the same location can get sick simultaneously due to shared environmental exposures rather than person-to-person transmission. These shared exposures might include toxins in food, water, air, or buildings; seasonal factors affecting humidity, temperature, and sunlight; concentrated EMF exposure in specific locations; or even deliberate releases of radiation or toxic aerosols (the book references historical government experiments like MK-ULTRA).

To illustrate how easily contagion can be misattributed, the book provides historical examples of conditions once thought contagious that were actually caused by nutritional deficiencies. Sailors suffering from scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) would develop severe symptoms including exhaustion, bleeding gums, and tooth loss, with many sailors in the same ship becoming ill simultaneously—appearing contagious but actually sharing the same deficient diet. Similar patterns occurred with beriberi (thiamine deficiency) and pellagra (niacin deficiency). The book also suggests that psychological factors might play a role in apparent contagion, noting how female roommates’ menstrual cycles sometimes synchronize without any germ involvement, and speculating about possible “invisible resonance between people that mimics germ-based contagion but is not understood by modern science.” These alternative frameworks challenge the need for a viral explanation of disease patterns typically attributed to contagion.

21. What is the “gold standard” method of virus isolation according to the book, and why is it considered problematic?

The gold standard method of virus isolation, according to the book, is the cell-culture method established by Thomas Peebles and Nobel laureate John Franklin Enders in their 1954 measles virus study. This method involves taking fluids from patients diagnosed with a disease, mixing those fluids with a “soup” of substances including antibiotics, various animal fluids (bovine amniotic fluid, horse serum, beef embryo extract), milk, phenol red, and human and monkey kidney cells. When cells in this mixture break down (exhibit the cytopathic effect), researchers conclude that a virus from the patient samples caused this breakdown.

This method is considered fundamentally problematic by No Virus advocates for several reasons. First, it never actually isolates a virus as an independent entity separate from all other cellular material. Instead, it relies on observing effects in a complex mixture and inferring the presence of a virus. Second, the breakdown of cells could be caused by many factors other than a hypothetical virus, including the experimental conditions themselves—the antibiotics, starvation conditions, and toxic substances in the mixture. Dr. Lanka explicitly describes how researchers are “killing those cells, intoxifying them with cytotoxic antibiotics, starving them to death” and then mistakenly attributing the resulting cell death to a virus. Third, even Enders and Peebles themselves acknowledged limitations in their paper, stating that “cytopathic effects which superficially resemble those resulting from infection by the measles agents may possibly be induced by other viral agents present in the monkey kidney tissue…or by unknown factors.” Despite these admitted limitations, this methodology became the unquestioned standard for modern virology.

22. How does the book describe the impact of Watson and Crick’s DNA work on virology?

Watson and Crick’s 1953 paper published in Nature, which announced DNA’s double-helix structure, fundamentally transformed how scientists conceptualized viruses and disease causation. According to Dr. Stefan Lanka, this discovery initiated the field of molecular biology, which examines how genes influence chemical processes within cells. The book quotes Lanka directly on this shift: “From that moment on, the causes of disease were thought to be in the genes. The idea of a virus changed, and overnight a virus was no longer a toxin, but rather a dangerous genetic sequence, a dangerous DNA, a dangerous viral strand, etc.”

This paradigm shift redirected virology from studying toxic substances to focusing on genetic material. The book suggests this reconfiguration was accompanied by substantial research funding, as “this new genetic virology was founded by young chemists who…had unlimited research money.” The implication is that Watson and Crick’s work created an entirely new framework for understanding disease causation that moved away from environmental and systemic factors toward genetic explanations. Viruses, which had previously been conceived of as poisons or toxins in various forms, were reconceptualized as infectious genetic material capable of replication. This fundamental shift in perspective underpins modern virology but, according to the No Virus position, was driven more by theoretical assumptions following Watson and Crick’s work than by proper experimental validation of these new virus concepts.

23. What historical examples of misdiagnosed diseases (like scurvy) does the book use to support its arguments?

The book presents several compelling historical examples of diseases once thought to be contagious that were later discovered to be caused by nutritional deficiencies. Scurvy is highlighted as a deadly condition that killed more than 2 million sailors starting in the Christopher Columbus era. Sailors in close proximity would develop identical severe symptoms including exhaustion, tooth loss, gum ulcerations, spontaneous bleeding, limb pain, swelling, and anemia. Though this pattern appeared to suggest contagion, scurvy was eventually proven to be caused by vitamin C deficiency and was resolved by adding citrus fruits to sailors’ diets.

Beriberi is presented as another example, a condition affecting the nerves, heart, digestion, and limbs that is now known to be caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency rather than contagion. Similarly, pellagra, which causes skin lesions along with neurological and gastrointestinal disturbances, was eventually linked to niacin (vitamin B3) deficiency after being misunderstood. These historical cases demonstrate how easily disease patterns can be misattributed to contagion when the true cause lies elsewhere. The book uses these examples to suggest that current disease patterns attributed to viruses might similarly have non-contagious origins that are being overlooked due to the dominant germ theory paradigm. This historical perspective offers a precedent for how entire medical frameworks can be based on false assumptions about disease causation for extended periods before being corrected.

24. What does the “Settling the Virus Debate” document propose, and what has been the response to it?

The “Settling the Virus Debate” document, published in July 2022 and signed by twenty doctors, scientists, and researchers who support the No Virus position, proposes specific scientific protocols that virology laboratories around the world could follow to definitively resolve the question of viral existence. The document outlines precise methodologies that would allow for proper isolation of viruses and controlled experiments that follow the scientific method, thereby addressing the core criticisms that the No Virus advocates have raised against conventional virology practices.

According to the book, more than a year after the document’s publication, there had been no response from the virology establishment. No laboratories had taken up the challenge to conduct the proposed experiments that could potentially validate or invalidate the No Virus position. The book notes that Dr. Stefan Lanka did not sign this document because he “feels that virology has already been refuted and there isn’t a need to offer virology any more challenges.” The lack of response to this formal proposal is presented as telling—suggesting that either the virology establishment is unwilling to subject its foundational claims to proper scientific scrutiny, or they recognize that such experiments might undermine the field’s basic premises. The document represents an explicit challenge to virology to prove its claims using the scientific method, with the ongoing silence interpreted as significant by the No Virus advocates.

25. How does the book explain the divide within the health freedom community regarding the “No Virus” position?

The book characterizes a significant division within the health freedom community—a group that generally challenges aspects of mainstream medicine—regarding the No Virus position. While this community typically questions vaccines, pharmaceutical interventions, and other elements of the allopathic medical model, many draw the line at the claim that viruses don’t exist at all. For most health freedom advocates, the No Virus position “goes too far,” creating an acrimonious divide among people who otherwise share many criticisms of conventional medicine.

This division is explained partially by suggesting that many health freedom advocates haven’t properly studied or understood the No Virus arguments, with the book stating that “their rebuttals often suggest that they haven’t studied the rationale for the position” and “many of them aren’t even aware of what the No Virus position is truly claiming, or why.” The book cites Henry Bauer, who foresaw this division following the HIV-AIDS debates, calling for an “extended and explicit analysis” of the matter. The book also notes that even Dr. Peter Duesberg, a prominent HIV-AIDS dissenter, strongly disagreed with the No Virus view, calling the divide “tragic.” This internal conflict is presented as particularly significant because it fragments a community that might otherwise be united in challenging medical orthodoxy, with the No Virus position representing a more fundamental challenge to the entire paradigm of allopathic medicine than many health freedom advocates are prepared to accept.

26. What criticisms does the book make about the original genetic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2?

The book presents scathing criticisms of the original genetic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2, focusing primarily on methodological failings. Dr. Mark Bailey argues that the research team merely “assembled an in silico ‘genome’ from genetic fragments of unknown provenance, found in the crude lung washings of a single ‘case'” of COVID-19. The term “in silico” is emphasized as problematic because it refers to a computational model rather than a physical entity isolated from nature. Dr. Andrew Kaufman describes this as an “artificial version of something that doesn’t exist” that is essentially “man-made.”

The fundamental criticism is that without first isolating and purifying the virus, researchers cannot determine whether the genetic material they’re analyzing comes from a virus or from other cellular material in the sample. The book argues that scientists merely assumed the genetic fragments originated from a virus without establishing this through proper isolation procedures. Additionally, the lack of proper controls in the sequencing process is highlighted as a serious methodological flaw—scientists should have run the sequencing on various samples, including those without the alleged virus, to validate their findings. Dr. Bailey summarizes this critique by noting that all researchers had was “a 41-year old man with pneumonia and a software-assembled model ‘genome'” rather than a physically isolated virus particle whose genetic material could be directly sequenced. Despite these limitations, the book argues, this computer-assembled genome was presented to the public as definitive proof of the virus’s existence and structure.

27. How does the book characterize the majority of scientists who work in virology?

The book offers a nuanced characterization of virologists, avoiding blanket accusations of deliberate deception while still fundamentally challenging their work. It states that the No Virus position “does not intend to imply that the majority of hardworking scientists and doctors are willfully conspiring and lying—although it doesn’t deny that some of them are intentionally bad actors.” Instead, it suggests that most well-meaning scientists have unknowingly inherited and perpetuated fundamental problems “baked into the foundations of virology.”

Two primary explanations are offered for why so many intelligent scientists might accept flawed methodologies. First, many simply haven’t thought to question what they were taught during their education and training. Second, those who do recognize problems might be “too afraid to challenge the establishment’s positions because the implications would be too devastating for the entire field” and for their own careers. The book employs the phrase “go along to get along” to describe how scientists might avoid confronting foundational problems to maintain professional standing. It also draws a parallel to how “many Ponzi schemes have successfully defrauded otherwise savvy investors” to illustrate how intelligent people can be collectively misled. This characterization presents most virologists not as deliberate perpetrators of scientific fraud but as unwitting participants in a field built on problematic foundations, with career incentives and institutional structures discouraging critical examination of its basic premises.

28. What are the social and political implications of the “No Virus” theory according to the book?

The book presents the social and political implications of the No Virus theory as profound and far-reaching, particularly regarding pandemic responses and public health policies. It explicitly states that “from a public-health-policy perspective, the differences are massive” between believing and not believing in transmissible viruses. If deadly viruses cannot be transmitted between people, then measures like lockdowns, mask regulations, vaccine mandates, business closures, and surveillance implemented during COVID-19 would be entirely unjustified. As the book puts it: “the deadly virus justifying the measures didn’t exist in the way that we’ve been told.”

Beyond COVID-19, the book suggests even broader implications: “without an ‘invisible enemy,’ any future pandemics—and associated tyrannical measures—wouldn’t be possible.” This frames the virus narrative as a potential tool for implementing social control, with the belief in deadly invisible pathogens enabling government overreach that would otherwise be rejected. The book characterizes this as “far more than an intellectual exercise,” implying that the No Virus position has direct relevance to preserving freedom and preventing unwarranted restrictions. This perspective reframes pandemic policies not as necessary public health measures but as “tyrannical” interventions premised on a fundamentally flawed understanding of disease causation, suggesting that accepting the No Virus position would undermine the justification for such interventions in both present and future scenarios.

29. How does the book describe the work of the Perth Group in Australia regarding HIV?

The Perth Group in Australia is described as conducting extensive analyses on HIV isolation and publishing peer-reviewed papers challenging the mainstream narrative. The book mentions that the group produced a detailed scientific paper titled “HIV—a virus like no other” (available for free on their website, theperthgroup.com) that critiques the foundational HIV studies. The Perth Group falls within the “No Virus” camp, arguing that researchers working on HIV were mixing substances in test tubes and taking microscope images, but never actually found an isolated, purified virus—only a “soup” of cellular material that they assumed contained HIV.

The book references Neville Hodgkinson, formerly a medical and science correspondent for prominent British newspapers, who published articles about the Perth Group’s work, including a summary of its six key assertions. While the book doesn’t elaborate on these specific assertions, it positions the Perth Group as significant scientific contributors to the No Virus perspective regarding HIV. Their work is presented as part of a broader scientific challenge to conventional virology rather than as fringe speculation, with their peer-reviewed publications lending credibility to the No Virus position. The Perth Group’s analyses of HIV are thus framed as important precedents for the later challenges to SARS-CoV-2 and other alleged viruses, establishing a historical continuity in the scientific critique of viral isolation methods.

30. What specific statements from the CDC and other health agencies does the book cite regarding virus isolation?

The book cites several remarkable statements from health agencies that No Virus advocates interpret as admissions that proper virus isolation has never been achieved. Most prominently, the CDC’s November 2, 2020 response to a Freedom of Information request stated: “A search of our records failed to reveal any documents pertaining to your request” for records describing the isolation of SARS-COV-2. In a subsequent March 1, 2021 response, the CDC made an even more telling statement: “The definition of ‘isolation’ provided in the request is outside of what is possible in virology.” The No Virus position interprets this as an explicit acknowledgment that virology cannot follow the scientific method’s requirement for isolating an independent variable.

New Zealand’s Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) responded on July 19, 2022, that it “has not performed any experiments to scientifically prove the existence of SARS-CoV-2 virus.” In a separate request, ESR also admitted on August 17, 2022, that it “has not performed any experiments to scientifically prove that [the] SARS-CoV-2 virus causes COVID-19.” The Public Health Agency of Canada stated on December 20, 2021, that “the isolation of a virus cannot be completed without the use of another medium….The gold standard assay used to determine the presence of intact virus in patient samples is virus isolation in cell culture.” The UK Health Agency cited a “national security” exemption to avoid providing details about control methods, claiming this would “directly contravene an explicit request from the World Health Organization.” These statements from multiple health agencies across different countries are presented as institutional admissions that proper virus isolation—as defined by the scientific method—has never been achieved.

31. How does the book explain the origin and attribution of “spike proteins” if not from viruses?

The book addresses the question of spike proteins by applying the same fundamental critique used throughout the No Virus position—without first isolating a virus, researchers cannot prove that any cellular material, including spike proteins, originates from a virus. The basic argument is that if the virus hasn’t been properly isolated as an independent entity, scientists cannot legitimately claim that spike proteins or any other genetic material comes from a hypothetical virus. The book states this principle directly: “any material alleged to ‘come from a virus’ such as ‘spike proteins’ can’t be known to come from a virus if the virus hasn’t been isolated first.”

This perspective suggests that when researchers identify and study what they call viral spike proteins, they are actually examining cellular material that may have entirely different origins having nothing to do with viruses. The book indicates that researchers are observing real biological structures or materials but misattributing their source due to preconceived theoretical frameworks. By questioning the origin of spike proteins, the No Virus position challenges not only the specific claims about SARS-CoV-2 structure but also the foundations of research focused on viral proteins, antibody responses to these proteins, and vaccine development targeting them. While the book doesn’t offer an alternative explanation for what spike proteins might be if not viral components, it maintains that claiming they come from viruses represents an unproven assumption rather than a scientifically established fact.

32. What does the book claim about virus variants and how they are identified?

The book presents a critical view of how viral variants are identified and classified, arguing they are essentially statistical artifacts rather than actual biological entities. According to the No Virus perspective, alleged “variants” are simply different combinations of genetic fragments patched together in computers to create slightly different overall results compared to previously established “template” genomes. Dr. Andrew Kaufman is quoted explaining that the identification of variants represents “an inability to find an exact match of previously patched-together genomes.”

Rather than interpreting these genetic variations as evidence of viral evolution, the No Virus position suggests they should be understood as failures to reproduce experimental results. However, instead of acknowledging these inconsistencies as problems with their methodology, virologists reframe them as discoveries of new variants. The fundamental issue remains the same as with original virus identification—without first isolating and purifying a virus, scientists cannot determine whether the genetic material they’re analyzing comes from a virus or from other cellular debris. The establishment of “template” genomes allows researchers to look for specific genetic patterns, but finding matches or near-matches to these templates doesn’t prove viral existence or evolution. Instead, the No Virus position argues that the entire framework of variant identification represents circular reasoning built upon the unproven assumption that the original template genome came from a virus.

33. How does the book explain the historical foundations of germ theory before microscopes could visualize viruses?

The book highlights the speculative nature of early germ theory, noting that scientists claimed viruses caused disease long before technology existed that could visualize particles of that size. For instance, Louis Pasteur suspected a tiny virus existed through his work on rabies in the late 19th century, but he never actually saw a virus because the microscopes of that era couldn’t detect such small particles. The book raises the question: “How did he know it was there if he didn’t see it?” suggesting that early viral theory was based on assumption rather than direct observation.

The electron microscope, which could theoretically visualize virus-sized particles, wasn’t invented until the 1930s, and wasn’t used in clinical virology until around 1948, with commercial versions becoming widely available only in the 1960s and 1970s. Despite this technological limitation, the alleged discovery of the first virus—the Tobacco Mosaic Virus—occurred in 1903 through Dmitri Ivanovsky’s work. Similarly, Peyton Rous’s 1911 research claimed to find a “transmissible agent” causing tumors in chickens (later named Rous sarcoma virus), for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1966. The book emphasizes that these early “discoveries” relied solely on indirect evidence since no virus was actually seen. From the No Virus perspective, this historical sequence reveals that the concept of disease-causing viruses was established as a theoretical framework before technology existed that could potentially verify their existence, suggesting the field began with assumptions that were never properly validated even after visualization became technically possible.

34. What does the book say about the relationship between Louis Pasteur and Antoine Béchamp?

The book briefly mentions the contentious relationship between Louis Pasteur and Antoine Béchamp as representing two opposing perspectives in the history of microbiology and disease theory. While Pasteur is widely credited with developing the germ theory of disease and is regarded as a hero in allopathic medicine, the book notes that “in other circles he is vilified as a ‘plagiarist and impostor,’ while his contemporary Antoine Béchamp is lauded as a hero.” This division reflects a historical scientific controversy that continues to influence alternative perspectives on disease causation.

The book references Ethel Hume’s 1923 book “Béchamp or Pasteur? A Lost Chapter in this History of Biology,” suggesting that this conflict represents more than a simple personality clash but rather fundamentally different scientific paradigms. Additionally, the book cites historian Gerald Geison’s 1995 book published by Princeton University Press, which evaluated Pasteur’s private notebooks and revealed “sometimes astonishing…discrepancies between the results reported in [Pasteur’s] published papers and those recorded in his private manuscripts.” This suggests potential scientific misconduct that might have influenced the development of germ theory. While not extensively developing this historical relationship, the book uses the Pasteur-Béchamp controversy to indicate that the dominance of germ theory over alternative understandings of disease was not inevitable or based solely on scientific merit, but may have been influenced by factors including questionable research practices and personality politics.

35. How does the book address the issue of proving a negative in the context of the “No Virus” position?

The book acknowledges the fundamental logical challenge faced by the No Virus position: “a negative can’t be proven. It’s not possible to prove that something doesn’t exist.” This represents an inherent limitation to any argument claiming the non-existence of something, as there always remains the possibility that “maybe we just haven’t found it yet.” The book illustrates this principle by noting that it’s similarly impossible to prove that a “flying spaghetti monster” doesn’t exist—a reference to a satirical deity created to challenge unfalsifiable religious claims.

However, rather than seeing this as invalidating the No Virus position, the book presents it as a reason why the burden of proof should rest with those claiming viruses do exist. Since virologists are making the positive claim that disease-causing viruses exist, they should be required to demonstrate this conclusively through proper scientific methodology. The No Virus position maintains that this burden has never been met due to the methodological flaws in virus isolation studies. The book presents initiatives like the “Settling the Virus Debate” document as attempts to address this issue by proposing specific scientific protocols that could potentially resolve the matter. While acknowledging the impossibility of definitively proving viruses don’t exist, the No Virus position focuses instead on demonstrating the inadequacy of the evidence presented for their existence, shifting the debate from proving a negative to evaluating the quality of evidence for a positive claim.

36. What specific challenges in isolating viruses does the book address, and how does it respond to them?

The book examines several challenges that mainstream virologists cite as reasons why they cannot isolate viruses according to the proper definition of isolation, and provides No Virus responses to each. One common claim is that “not enough of the virus is present in any bodily fluid of any sick person” to isolate it directly. Dr. Thomas Cowan responds to this by questioning: “On what theory are we then claiming the virus is making people sick?” and notes that when Dr. Kaufman asked scientists if pooling samples from 10,000 COVID patients would provide enough virus to isolate, the answer remained negative.

A second claim is that viruses are intracellular parasites and therefore cannot be found outside cells. The No Virus position counters this by pointing out that virologists simultaneously claim viruses travel between people outside of cells: “It buds out of the cell, goes into a droplet and travels to the next person.” Dr. Cowan questions why virologists can’t isolate viruses during this transmission phase. A third claim is that technology doesn’t exist to isolate particles as small as viruses, which Dr. Kaufman counters by noting that exosomes and bacteriophages of similar size have been successfully isolated. Dr. Lanka adds that bacteriophages “could be photographed, isolated as whole particles, and all their components could be biochemically determined and characterized,” proving that such isolation is technically possible. The book also mentions the HART organization’s admission that “there has never been a pure isolate of SARS-CoV-2 virus” with the remarkable suggestion that “this could be because no-one has tried hard enough.” These responses challenge the validity of the excuses offered for failing to properly isolate viruses.

37. How does the “No Virus” position explain the apparent success of vaccines if viruses don’t exist?

Interestingly, the book does not directly address how the No Virus position explains the apparent success of vaccines if viruses don’t exist. This represents a significant gap in the presentation of the No Virus argument, as the perceived effectiveness of vaccines in preventing diseases traditionally attributed to viruses would seem to present a strong challenge to the claim that such viruses don’t exist. While the book extensively discusses methodology problems in virology, alternative explanations for disease, and issues with the genetic sequencing of alleged viruses, it does not provide a specific alternative framework for understanding how vaccines might appear to work in the absence of the viruses they supposedly target.

The closest the book comes to addressing this issue is in its discussion of “antiviral” drugs, which it reframes as “antimetabolic agents” that affect cellular processes rather than targeting viruses specifically. A similar reframing might be applied to vaccines, suggesting they produce effects through mechanisms other than conferring immunity against non-existent viruses, but the book doesn’t explicitly make this argument. This omission is notable given how central vaccines are to conventional virology and public health practices. The absence of a direct explanation for vaccine effectiveness could be seen as a significant limitation in the No Virus position as presented in this text, leaving readers without clarity on how this alternative paradigm would explain one of the most commonly cited pieces of evidence for the existence and disease-causing properties of viruses.

38. What role do cellular vesicles and misidentification play in the “No Virus” argument about electron microscopy?

The book presents misidentification of cellular structures as a critical problem in viral electron microscopy, arguing that researchers often mistake normal cellular components for viruses. It cites a 2020 paper in Kidney360 titled “Appearances Can Be Deceiving—Viral-like Inclusions in COVID-19 Negative Renal Biopsies by Electron Microscopy” and an April 2021 article in the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, which admits to difficulties differentiating coronaviruses from subcellular structures. The CDC article explicitly acknowledges that investigators have “inaccurately reported subcellular structures, including coated vesicles, multivesicular bodies, and vesiculating rough endoplasmic reticulum, as coronavirus particles.”

Dr. Samantha Bailey raises a fundamental question about this situation: if experts claim to know what viruses look like under electron microscopy, how did they establish this standard without first properly isolating the virus? She explains that the template for identifying coronaviruses comes from a 1967 study that itself was looking at mixtures in cell culture soups rather than isolated viruses. These researchers declared certain particles to be viruses based on their resemblance to another alleged virus (avian infectious bronchitis virus) that had also never been properly isolated. Bailey describes these particles as “cellular vesicles of unknown significance” rather than viruses, and humorously refers to them as “UVOs (unidentified viral objects).” The No Virus position thus argues that viral identification in electron microscopy represents circular reasoning—particles are identified as viruses because they look like other particles previously called viruses, without any party ever establishing through proper isolation that the particles in question are actually viruses rather than normal cellular components.

39. How does the book explain the concept of “UVOs” (unidentified viral objects) and their significance?

The term “UVOs” (unidentified viral objects) is introduced in the book as Dr. Samantha Bailey’s humorous yet pointed characterization of particles that virologists claim are viruses in electron microscopy images. This term, playing on the acronym UFO (unidentified flying object), highlights the No Virus position that these particles have not been properly identified as viruses through scientific methodology. Bailey describes these particles as “cellular vesicles of unknown significance” rather than confirmed viral entities, suggesting they are normal cellular components being misinterpreted.

The significance of the UVO concept lies in how it challenges the entire framework of viral identification in electron microscopy. When scientists claim to see viruses under electron microscopes, they are identifying particles based on morphological similarity to template images from previous studies. However, the No Virus position argues that these template images themselves were never properly validated as showing viruses. The book cites the example of coronavirus identification, where current identification is based on a 1967 study that itself was looking at mixtures in cell cultures rather than isolated viruses. Those researchers identified particles as coronaviruses based on resemblance to “avian infectious bronchitis virus,” which also had never been properly isolated. This creates a chain of circular reasoning where particles are identified as viruses solely because they resemble other particles previously called viruses, with no point in the chain including proper isolation and verification. The UVO concept thus highlights how viral identification relies on pattern recognition based on unverified templates rather than scientific confirmation of the particles’ nature and origin.

40. What specific resources and researchers does the book recommend for further exploration of the “No Virus” position?

The book provides an extensive list of resources and researchers for those interested in exploring the No Virus position further. Dr. Mark Bailey’s “A Farewell to Virology” (September 2022) is highlighted as a “seminal, technical piece” critiquing foundational virology studies claiming to have isolated SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses, available for free at drsambailey.com. Also mentioned is “The End of COVID,” a 150-plus-hour online library of videos discussing the No Virus position launched by Alec Zeck and Mike Winner in mid-2023 at theendofcovid.com, which reportedly gained over 100,000 sign-ups in its first weeks.

Dr. Samantha Bailey, a former health presenter on New Zealand television, is recommended for her videos explaining the No Virus perspective “in an easy-to-understand manner,” available at drsambailey.com/resources. Mike Stone’s website ViroLIEgy.com is cited as covering these topics in detail. Books recommended include “Virus Mania” by Torsten Engelbrecht and colleagues (originally published in 2007, updated in 2021) and “What Really Makes You Ill?” (2019) by Dawn Lester and David Parker. Other key researchers mentioned throughout the book include Drs. Thomas Cowan, Andrew Kaufman, and Stefan Lanka, with the Perth Group in Australia noted for their work on HIV. German virologist Dr. Stefan Lanka is particularly highlighted for his experimental work and court cases challenging virus isolation claims. These resources span websites, video collections, books, scientific papers, and legal documents, providing multiple entry points for examining the No Virus perspective.

Subscribe to Lies Are Unbecoming

Related Posts

“Vax Hesitancy” and “Vax Hesitant” people did not exist before ‘covid’. It is an umbrella term that allows for no nuances… Why

was the idea introduced ?

Normal people have been studied for decades (Freud’s depth psychology; BF Skinner’s behaviour studies; neuro-psychology)… The Rulers Of The Universe didnt ‘impose’ a global lock-down, and mandate toxic injections just to test whether the Normies would react obediently and submissively –

as They already knew they would… No, They wanted to flush out any forms of ‘resistance’ so they could be studied, and methods devised so that when the time arrives to herd the masses into the global digital prison all, or nearly all of the

‘hesitants’ will comply…

There’ll be Big Brother’s Room 101 for the very few who’re still

able to refuse (Room 101 being the concentration camps (aka – quarantine centres) where they’ll be thoroughly studied, experimented on, and so on)…