Welcome to the Surveillance Renaissance

by Didi Rankovic | May 9, 2024

A scandal is shaping up in the US, linked to the use by law enforcement of Cybercheck’s AI (machine learning) software, owned by Canada’s Global Intelligence.

Cybercheck has been used almost 8,000 times by hundreds of police departments and prosecutors in 40 states, to help them shed light on serious crimes like murder and human trafficking.

But despite the officials “embracing” the software, and its makers defending it, those on the other side of the legal process, defense attorneys, are leveling some serious accusations.

Imagine a scenario where your entire digital life is visible to an algorithm that’s constantly judging whether you might be a criminal. Cybercheck can dissect vast swathes of internet data with ease, prying into personal lives without a warrant or a whisper of consent. The potential for abuse is not just a paranoid fantasy but a pressing concern.

The reliability of the software, transparency, and the trustworthiness of Cybercheck founder Adam Mosher are all being called into question.

Cybercheck is supposed to help gather evidence by providing data extracted from publicly available sources – something the company refers to as “open source intelligence.”

That means email addresses and accounts on social media, and other components from the trail of personal information people leave on the internet. The purpose is to physically locate suspects, and provide other data needed by law enforcement.

But the problem, according to critics, is that despite its widespread use and the consequences – namely, putting people in prison for serious crimes – Cybercheck continues to by and large fly under the radar.

Not surprising, given that the “open source intelligence” gathering software is itself closed-source and proprietary. And that means nobody except those behind it know exactly what methods it uses and how accurate it is.

On top of that, Mosher himself is accused of lying under oath about his own expert skills and the way the tool has been used.

That is the point that defense attorneys have formally made via a motion filed in Ohio, which demands that Cybercheck’s algorithms and code be made available for inspection.

Naturally, Mosher argued this was not possible because that technology is proprietary. The motion is part of a murder case handled by the Akron Police Department.

The Akron case saw two men who men, who deny committing the crime, indicted on what Mosher calls “entirely circumstantial” evidence (shell casings at the scene originating from a gun that was in one of the suspect’s homes, and a car, registered to the other, spotted on security camera footage near the scene).

But there was also evidence that came from Cybercheck, who tied the suspects’ physical location to the scene of the robbery and shooting by letting algorithms go through their social profiles and searching the web for other information.

In the end, a network address from a device connected to the internet obtained from a security camera’s Wi-Fi is what was taken as part of evidence sufficient to indict.

And although a camera was involved, no footage of the deadly incident exists. Another thing that doesn’t exist is information about how exactly Cybercheck, to quote an NBC report, “found the camera’s network address or how it verified that the device was at the scene.”

More details that forensic experts hired by the defense weren’t able to ascertain is how Cybercheck verified an email address as allegedly used by both suspects, and these experts also could not “locate” a social account mentioned in a report prepared by Cybercheck.

It looks like police and prosecutors were happy to take not only this evidence – or “evidence” – at face value, but also take Mosher’s word for it, when he testified that Cybercheck’s accuracy is “98.2%.”

Yet, there is no information how he arrived at this number. But Cybercheck founder did – in this filing from the summer of 2023 and a previous one – share that the software has not undergone peer-review at any point.

However, in a third murder case, also in Akron, Mosher last fall claimed that the University of Saskatchewan did in fact peer-review it. But the 2019 document “appears to be an instructional document for the software and doesn’t say who performed the review or include their findings,” reports NBC.

A spokesman for the university denied that the document was ever peer-reviewed.

Now it is up to the judge to decide whether to force Mosher to reveal the code powering the controversial tool.

Civil liberties are not just under threat; they’re on the chopping block. Cybercheck’s prowess in data mining could be weaponized to suppress free speech and keep tabs on political dissenters. It’s a short walk from using tech to track criminals to using it to monitor anyone who doesn’t toe the line. In the digital echo chamber, this tool could silently smother voices of dissent under the guise of public safety.

The mechanics of Cybercheck remain shrouded in secrecy. What decides the algorithm’s targets? Who ensures it doesn’t cross the line? The absence of transparency fuels a legitimate fear of a digital panopticon where algorithms have the final say over your data’s narrative. This shadow over how decisions are made and data is interpreted spells a dire need for open regulations and public oversight.

Currently, there’s something of a corporate commotion on the market for mass surveillance used by US law enforcement. The commotion is really just plain old consolidation of a lucrative market.

And this consolidation seems to be taking part like it often does in a booming industry; through mergers and acquisitions striving to cement and put the (economic) power in as few hands as possible.

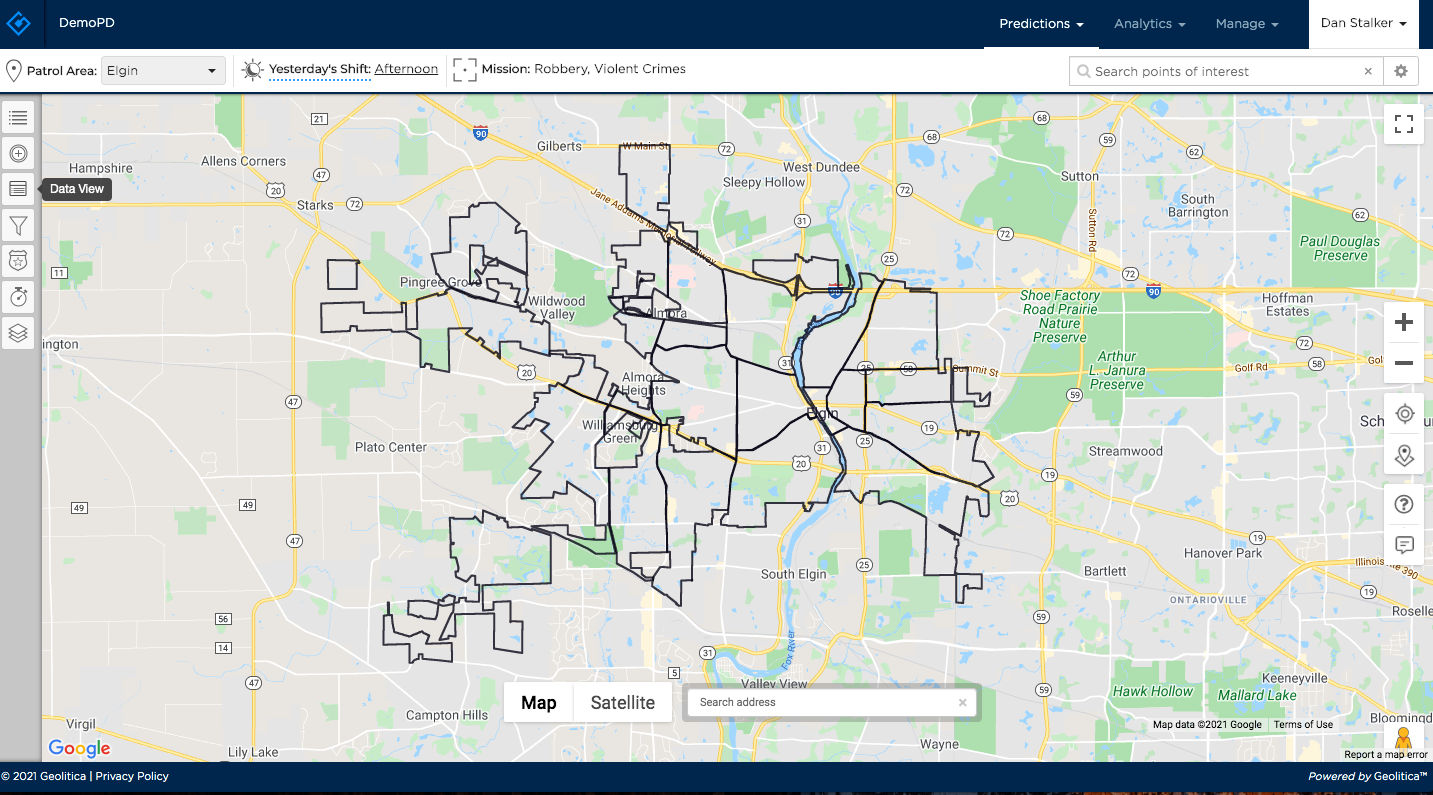

This time, it’s SoundThinking that is acquiring some segments of Geolitica, which developed PredPol (this was also the company’s name in the past), a predictive policing technology.

It looks like a classic tech industry takeover – picking apart a successful company, to buy its most valuable parts: engineers and patents.

“We are in a consolidation moment with big police tech companies getting bigger, and this move is one step in that process,” American University law professor Andrew Ferguson was once quoted as saying by Wired.

No offense to Ferguson’s credentials – he wrote The Rise of Big Data Policing – but his conclusion regarding this latest takeover is hardly rocket science-grade analysis. I.e., it’s pretty obvious what is going on here.

However, without going into more of the obvious – the significance on people’s privacy and therefore ultimately, if somewhat ironically, safety, let’s first meet the players here.

Even though these companies, often by design, by-and-large labor in obscurity, the main player, SoundThinking, doesn’t seem to need much introduction. Not if reports are already dubbing it “the Google of crime fighting” (“crime fighting” being a generous way of putting it).

No, the suggestion is that the company is amassing products and services in its particular industry just like Google has managed to do in its own. And that’s just not a good thing.

There’s been a lot of “rebranding” going on here, for good reason, because this type of business even if kept on the sidelines of mainstream media, has still managed to make a bad name for itself.

And so what SoundThinking once straight up called “predictive policing” – and the key product it sells to enable law enforcement to “achieve” this goal – is now referred to as “resource management for police departments.”

This player – not least with its upbeat, positive, wholesome name – “SoundThinking” – appears to be a shifty customer. And buyer.

The object of acquisition this time is Geolitica. Their website will tell you nothing – it is apparently a purveyor of “trusted services

for safer communities.”

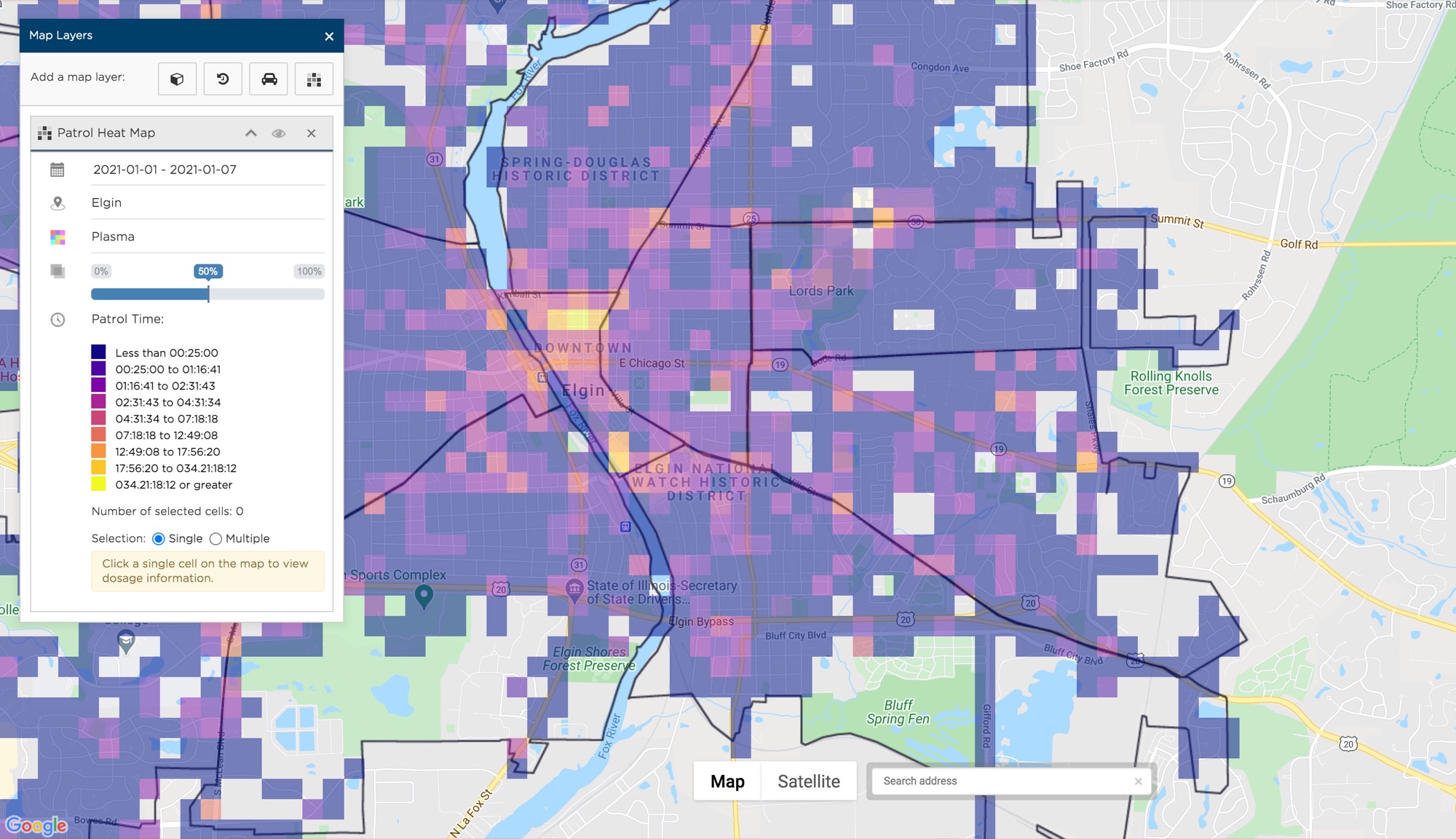

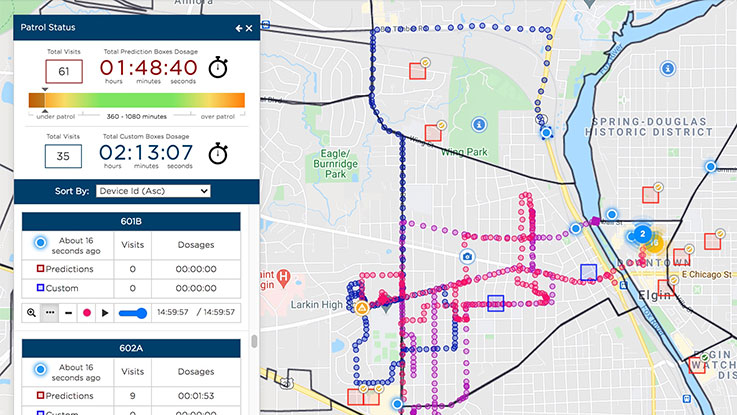

Digging just a little deeper into the corporate jargon, though, reveals, in roundabout ways, what this outfit is about: analyzing daily patrol patterns, managing patrol operations in real time, creating patrol heat maps, identifying resource hotspots.

There’s two key questions here, or perhaps three: does it work? Why does it need to be outsourced? And, how did the “Google of mass police surveillance” decide it was worth an acquisition (in part).

SoundThinking CEO Ralph Clark said in August that Geolitica’s patrol management clients would now become SoundThinking’s.

“We have already hired their engineering team (… it would) facilitate our application of AI and machine learning technology to public safety,” Clark at the time said during an earnings call with the company’s investors.

And yet, this is more than just a “post mortem” of some corporate deal. Some observers believe that what’s going on here is just one example, a brick in the wall, if you will, of what will eventually prove to have been a deep and comprehensive – not to mention controversial – shift in which the US government intends to proceed with the business of policing its communities.

Even that aside – for all the optimistic pronouncements about the value of a company like Geolitica (never forget, formerly called PredPol – and you don’t have to be an Orwell enthusiast to figure that contracted word out, nor its purpose and business) – there are misgivings.

And they go back as far as 2011, when – PredPol – first made it onto the scene, and went straight for using historical crime data to make current predictions.

“For years, critics and academics have argued that since the PredPol algorithm relies on historical and unreliable crime data, it reproduces and reinforces biased policing patterns” – that’s how a Wired report summed it up.

And yet it seems that in the years ahead, it is perhaps not the exact same technology, but no doubt – because why not, it is basically rewarded for “failing upwards” – this type of tools and services will “rule the waves” of US policing, where the current government looks suspiciously (no pun) prone to outsource it to private entities.

Highly likely – when all’s said, done, poured over, and investigated – to controversy with no end.

Tools like Geolitica are reminiscent of various technologies, and are designed to collect, analyze, and map vast amounts of geospatial data, creating detailed profiles that could be used by entities ranging from marketing agencies to government bodies. While such tools promise enhanced analytics, security, and targeted services, they simultaneously pose stark challenges to individual privacy and freedoms.

To understand the controversy, one must first understand Geolitica’s functionality. Imagine a tool capable of tracking movements, analyzing patterns, and predicting future locations of individuals based on a myriad of data points collected from smartphones, IoT devices, public cameras, and more. By merging artificial intelligence, big data, and geospatial technology, Geolitica creates a digital tapestry of an individual’s life with alarming accuracy.

The commercialization of personal data, known as surveillance capitalism, is another contentious point. Corporations harness tools like Geolitica to engage in relentless digital surveillance to gather behavioral data—often without explicit informed consent. This data is commoditized for targeted advertising, influencing buying behavior, and even manipulating opinions, stripping individuals of their privacy for commercial gain. Such practices not only foster a power imbalance between corporations and consumers but also create data monopolies that threaten market competition.

The use of Geolitica-like tools by governments raises the specter of “Big Brother” surveillance. The capability to track citizens’ whereabouts in real-time, under the guise of national security or public health, for example, presents a slippery slope toward authoritarianism. History is replete with examples where tools meant for protection were repurposed for citizen suppression. Unchecked, these technologies could be used to stifle dissent, target vulnerable communities, and unfairly advantage certain political agendas, fundamentally undermining democratic principles and civil liberties.

Law enforcement agencies increasingly rely on technological advancements to prevent crime and maintain public safety. One such advancement, predictive policing—exemplified by tools that we’ve covered before like PredPol—utilizes algorithms and data analytics to foresee where crimes are likely to occur.

Predictive policing doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It’s often part of a larger surveillance network, including CCTVs, license plate readers, and facial recognition technologies. While PredPol primarily analyzes patterns in historical crime data, the integration of more personal data sources can lead to significant privacy invasions.

Example: In Chicago, the police department’s use of a predictive system called the “heat list” or Strategic Subject List, which identified people likely to be involved in future crimes, raised alarms because it wasn’t clear how individuals were added to the list. People on the list were not notified but were subject to additional surveillance, an act seen as a direct violation of their privacy rights.

By focusing law enforcement attention on designated hotspots, predictive policing inadvertently restricts individuals’ freedom of movement. Residents in areas frequently marked as hotspots may experience repeated police interactions and unwarranted stops, creating a virtual fence that discourages free movement and contributes to community alienation.

Example: In New York City, a report showed that individuals in neighborhoods frequently targeted by predictive policing felt they were under constant surveillance and were less likely to engage in everyday activities, like visiting friends or attending community meetings, for fear of unwarranted police attention.

Knowing that certain behaviors or movements might trigger law enforcement attention, individuals might refrain from exercising their rights to assembly, speech, and association. This self-censorship, known as the chilling effect, can disrupt community bonds and civic engagement.

Subscribe to Reclaim the Net

Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Sitemap

© 2025 FM Media Enterprises, Ltd.

0 Comments