Beyond the Law

by Matt Taibbi | Sep 14, 2024

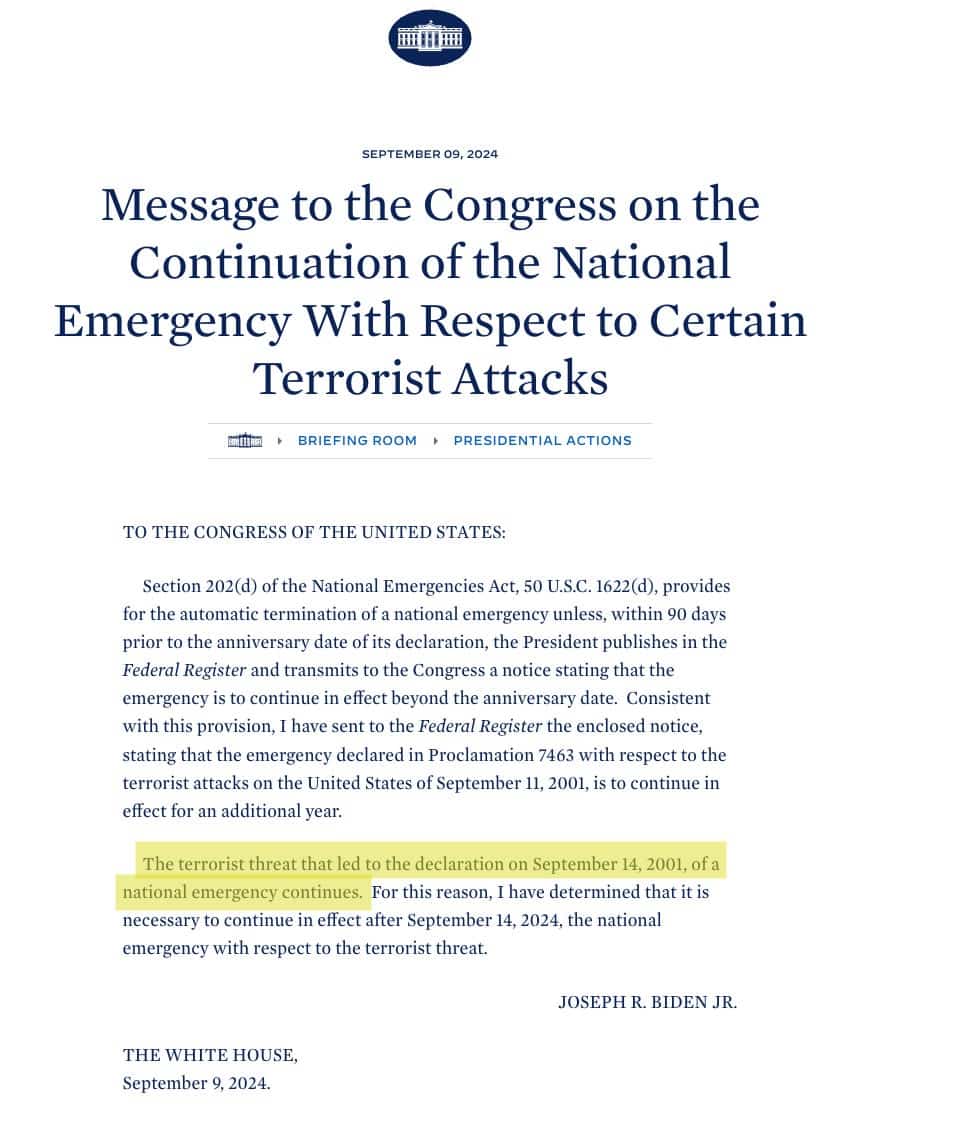

On September 14th, 2001, President George W. Bush signed Proclamation 7463 declaring a “National Emergency by Reason of Certain Terrorist Attacks.” The measure activates over 400 additional provisions of executive authority and has been re-signed every year by every succeeding president, including four times by Donald Trump. As discussed on the new America This Week, Joe Biden just signed its latest renewal, effective tomorrow, noting the threat of twenty-three years ago “continues”:

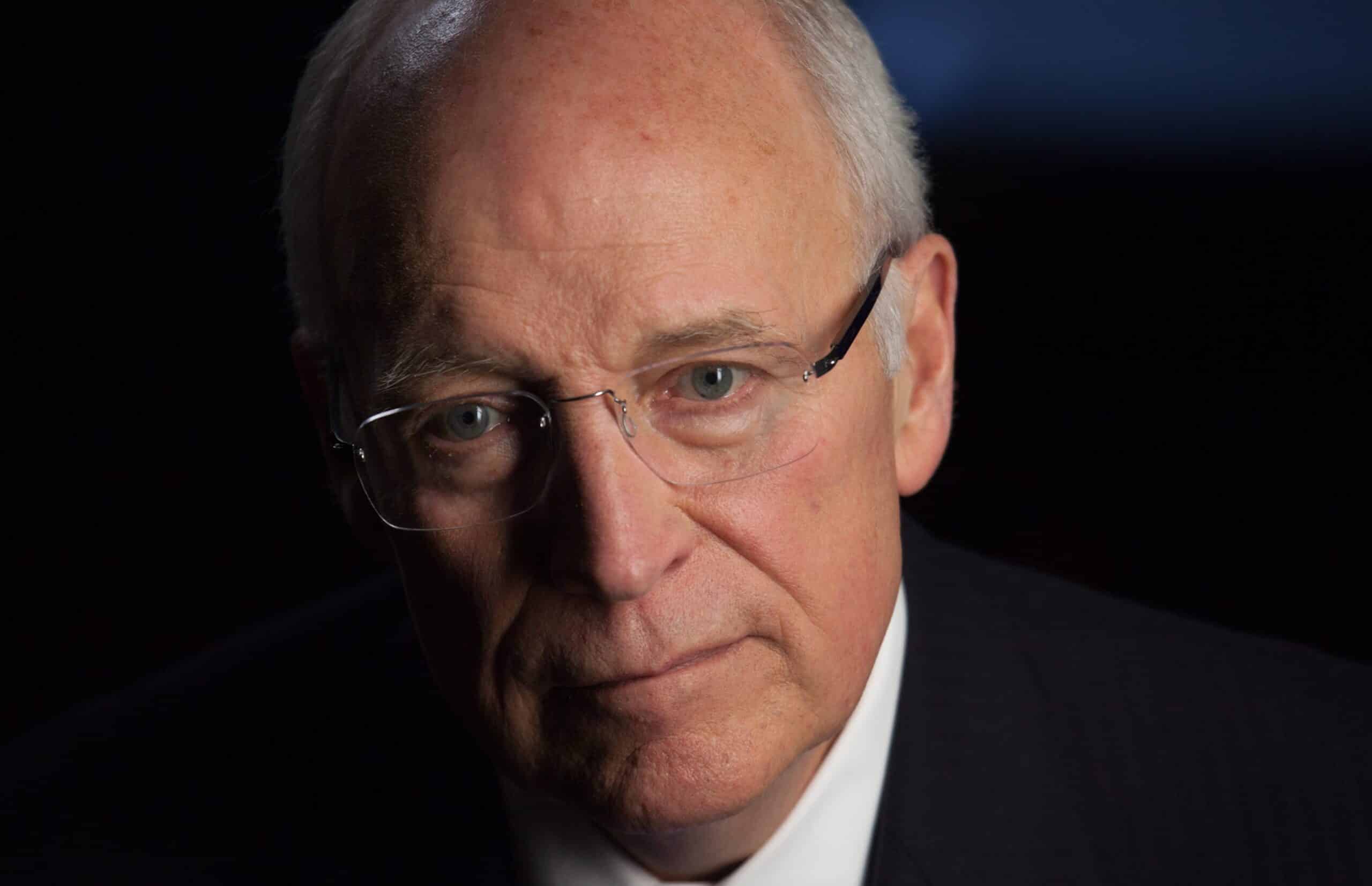

Along with 200 other Republicans, former Vice President Dick Cheney and former Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez just endorsed Kamala Harris. Gonzalez, who as George W. Bush’s counsel received and signed the infamous torture memos and dismissed the Geneva conventions as “quaint,” said in a Politico essay his reason was that Donald Trump represented a “threat to the rule of law.”

Cheney said Trump tried to use “lies and violence” to stay in power. Beyond pushing “enhanced interrogation” and conducting affairs of state through extralegal mechanisms like the Office of Special Plans, Cheney perfected the institutional whopper. His lies weren’t crazy and off-the-cuff, but monstrous and effective, like saying Saddam Hussein “is actively pursuing nuclear weapons” or had “high-level contacts with Al Qaeda going back a decade.” Putting a Trump lie in a class with one of Cheney’s is like comparing a flatus and a methane planet.

It’s the right metaphor, because that doesn’t mean the Trump experience smells great. But we’ve forgotten the scale of the other thing:

Along with 200 other Republicans, former Vice President Dick Cheney and former Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez just endorsed Kamala Harris. Gonzalez, who as George W. Bush’s counsel received and signed the infamous torture memos and dismissed the Geneva conventions as “quaint,” said in a Politico essay his reason was that Donald Trump represented a “threat to the rule of law.”

Cheney said Trump tried to use “lies and violence” to stay in power. Beyond pushing “enhanced interrogation” and conducting affairs of state through extralegal mechanisms like the Office of Special Plans, Cheney perfected the institutional whopper. His lies weren’t crazy and off-the-cuff, but monstrous and effective, like saying Saddam Hussein “is actively pursuing nuclear weapons” or had “high-level contacts with Al Qaeda going back a decade.” Putting a Trump lie in a class with one of Cheney’s is like comparing a flatus and a methane planet.

It’s the right metaphor, because that doesn’t mean the Trump experience smells great. But we’ve forgotten the scale of the other thing:

As New York smoldered 23 years ago, previously unimaginable debates entered American life. A glimpse into new obsessions appeared on October 21st, 2001, in a Washington Post article titled, “Silence of 4 Terror Probe Suspects Poses Dilemma for FBI.” Walter Pincus quoted FBI agents expressing “frustration” with an inability to generate leads through legal means. “We’re into this thing for 35 days and nobody is talking,” the official said, adding, “We’re known for humanitarian treatment… but it could get to that spot where we could go to pressure… where we won’t have a choice.”

At first it seemed the battle lines in the ensuing torture debate would be drawn as you’d expect: for and against.

The “for” position appeared (emphasis on appeared) to be argued by Harvard professor Alan Dershowitz, who was not yet a bugbear caricature to center-left America. Famous for stumping for due process rights of reviled individuals like Klaus von Bulow and Leona Helmsley, Dershowitz wrote a 2002 book called Why Terrorism Works thatasked if torture should be used in a “ticking time bomb” situation.

Torture was unconstitutional, but the United States was doing it, outsourcing the work by “rendering” suspects to places like Egypt and Jordan. Dershowitz believed “off the books” or “below the radar screen” practices were “antithetical to the theory and practice of democracy,” so his proposal was a formal system of warrants, which he believed would “decrease the amount of violence directed against suspects.”

Some conservatives cheered, more for the torture than the warrants, previewing years of advocacy by the likes of Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity. Amnesty International Director William Schultz headed the opposing view in an article in The Nation denouncing Dershowitz called “The Torturer’s Apprentice.” Schultz called torture “universally condemned and inherently abhorrent,” which was why “under international law, torturers are considered hostis humani generis, enemies of all humanity.”

In the end, neither side won. A bizarre third door emerged, through which American officialdom strode. Call it radical hypocrisy: a vision that didn’t fit traditional left-right paradigms, but was destined to dominate. A leading advocate was federal Judge Richard Posner, who made a show of opposition to Dershowitz, saying his ideas were “tinged with sadism.” But Posner lapped Dershowitz in creating a usable template for torture. First in a New Republic article and then in a series of books Posner argued that the rationale for torture was self-evident.

“If the stakes are high enough, torture is permissible,” he wrote. “No one who doubts that this is the case should be in a position of responsibility.” Posner went on, in a 2006 book called Not a Suicide Pact (as in, the Constitution is not a suicide pact!) to make an argument that took my breath away:

There is a long tradition of civil disobedience… Lincoln was engaged in civil disobedience when he suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War “on his own authority and when he defied an order by the chief justice of the United States granting habeas corpus to a Confederate sympathizer in the face of the suspension. But he was as right to disobey the law in his situation as Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were right to do so in their situations…

In the era of weapons of mass destruction, torture may sometimes be the only means of averting the death of thousands, even millions, of Americans… it would be the moral and political duty of the president to authorize torture.

We find permission to commit torture in the teachings of Gandhi was among the first expressions of the Orwellian mania destined to overtake American political thought. Posner also argued that because “consciences will not be shocked at the use of torture when it will ward off a great evil,” the question arises whether “we should relax the prohibition against torture in such a case, or trust public officers to perceive and act on a moral duty that is higher than their legal duty. I favor the latter course.”

In other words, torture should remain prohibited, but “public officers” should be encouraged to act on their “higher” moral duty when needed. Posner acknowledged allowing leaders to break the law this risked bringing it into “disrepute,” so he advocated defining torture narrowly. This would allow “necessary violations of law” while keeping those from becoming “routine.” The notion that torture should remain illegal but necessary became conventional wisdom. As Cornell’s Martin Sheffer put it, “during an emergency, the law of necessity supersedes the law of the Constitution.”

Dick Cheney’s War on Terror was built in the same shadow between illegality and necessity. Only the executive in possession of requisite character could know when or why a “public officer” needed to practice the “civil disobedience” of torture or assassination. The exercise of this authority required denying the privilege to everyone else. Courts and voters were by definition incompetent to judge those protecting national security. In other words, long before Trump was a blip on the radar of national politics, this “illegal but necessary” doctrine foresaw that the executive in possession of expanded power would need at least theoretical protection from a “rogue prosecutor or judge,” and eventually, from voters themselves.

Radical hypocrisy sooner or later requires a formal rejection of whatever prohibitions the executive is permitted to ignore. While officials may be content to live forever in a gray area between the law and “necessary violations,” the rest of the country will quickly grate at having to follow rules that no longer exist. There’s a reason we don’t dress judges in clown suits. The law can’t be a joke.

From the moment the public knew the government was engaging in torture, the Eighth Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment turned to plucked fruit, ripening to absurdity. Same with the right against unreasonable searches and seizures. Once NSA mass surveillance was exposed, source Edward Snowden was right to declare, “The Fourth Amendment… no longer exists.” (Snowden’s continued exile underscores the point.) The Fifth Amendment guarantee of due process has been rotting since Barack Obama’s government wrote memos giving itself permission to ignore it to drone American Anwar al-Aulaqi. More recently the Twitter and Facebook files, and admissions like Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s letter complaining of being “repeatedly pressured… to censor,” let citizens know the First Amendment has become a federal pissoir.

Illegal but necessary might sound pithy in the mind of someone like Richard Posner, but practically it makes voters want to stampede to the ballot to vote out the self-appointed Gandhis above. A government that openly proclaims the right to ignore restrictions on its power will inspire a protest movement. It could be led by Trump or a Trotsky, but it must happen. At that point, the “law of necessity” either has to be abandoned or formalized. We’re at that moment now, it seems. Either the emergency ends, or it becomes permanent. Who saw this coming all those years ago?

0 Comments