On the Brink

by Scott Ritter | Nov 23, 2024

There’s an old saying, “Fool around and find out.” On November 19, Ukraine fired six US-made missiles at a target located on Russian soil. On November 20, Ukraine fired up to a dozen British-made Storm Shadow cruise missiles against a target on Russian soil. On November 21, Russia fired a new intermediate-range missile against a target of Ukrainian soil.

Ukraine and its American and British allies fooled around.

And now they have found out: if you attack Mother Russia, you will pay a heavy price.

In the early morning hours of November 21, Russia launched a missile which struck the Yuzmash factory in the Ukrainian city of Dnipropetrovsk. Hours after this missile, which was fired from the Russian missile test range in Kapustin Yar, struck its target, Russian President Vladimir Putin appeared on Russian television, where he announced that the missile fired by Russia, which both the media and western intelligence had classified as an experimental modification of the RS-26 missile, which had been mothballed by Russia in 2017, was, in fact, a completely new weapon known as the “Oreshnik,” which in Russian means “hazelnut.” Putin noted that the missile was still in its testing phase, and that the combat launch against Ukraine was part of the test, which was, in his words, “successful.”

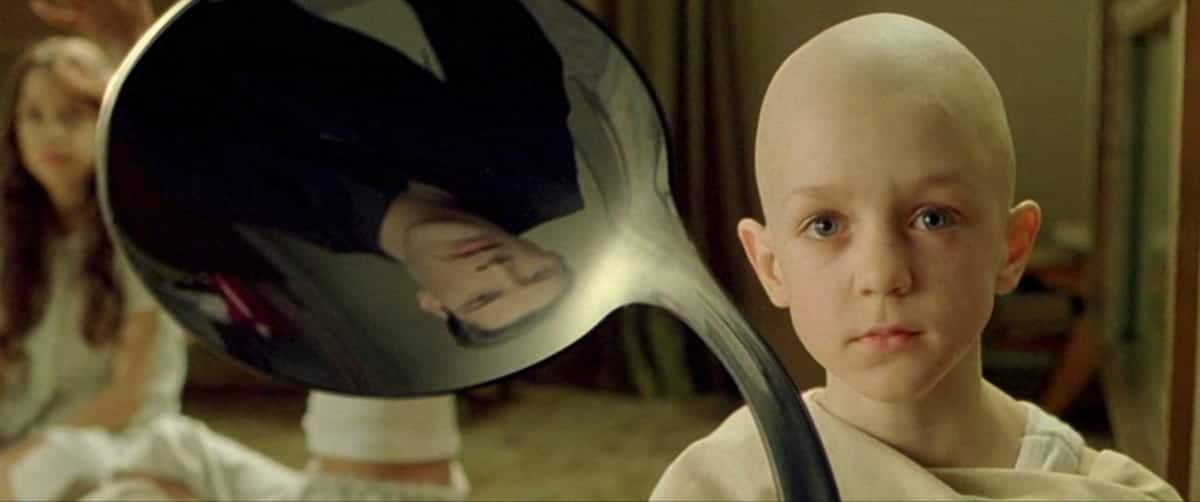

Russian President Putin announces the launching of the Oreshnik missile in a live television address

Putin declared that the missile, which flew to its target at more than ten times the speed of sound, was invincible. “Modern air defense systems that exist in the world, and anti-missile defenses created by the Americans in Europe, can’t intercept such missiles,” Putin said.

Putin said the Oreshnik was developed in response to the planned deployment by the United States of the Dark Eagle hypersonic missile, itself an intermediate-range missile. The Oreshnik was designed to “mirror” US and NATO capabilities.

The next day, November 22, Putin met with the Commander-in-Chief of the Strategic Missile Forces, Sergey Karakayev, where it was announced that the Oreshnik missile would immediately enter serial production. According to General Karakayev, the Oreshnik, when deployed, could strike any target in Europe without fear of being intercepted. According to Karakayev, the Oreshnik missile system expanded the combat capabilities of the Russian Strategic Missile Forces to destroy various types of targets in accordance with their assigned tasks, both in non-nuclear and nuclear warheads. The high operational readiness of the system, Karakayev said, allows for retargeting and destroying any designated target in the shortest possible time.

Scott will discuss this article and answer audience questions on Ep. 215 of Ask The Inspector.

“Missiles will speak for themselves”

The circumstances which led Russia to fire, what can only be described as a strategic weapons system against Ukraine, unfolded over the course of the past three months. On September 6, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin traveled to Ramstein, Germany, where he met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who pressed upon Lloyd the importance of the US granting Ukraine permission to use the US-made Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missile on targets located inside the pre-2014 borders of Russia (these weapons had been previously used by Ukraine against territory claimed by Russia, but which is considered under dispute—Crimea, Kherson, Zaporizhia, Donetsk, and Lugansk). Zelensky also made the case for US concurrence regarding similar permissions to be granted regarding the British-made Storm Shadow cruise missile.

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin (left) and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (right)

Ukraine was in possession of these weapons and had made use of them against the Russian territories in dispute. Other than garnering a few headlines, these weapons had virtually zero discernable impact on the battlefield, where Russian forces were prevailing in battle against stubborn Ukrainian defenders.

Secretary Austin listened while Zelensky made his case for the greenlight to use ATACMS and Storm Shadow against Russian targets. “We need to have this long-range capability, not only on the divided territory of Ukraine but also on Russian territory so that Russia is motivated to seek peace,” Zelensky argued, adding that, “We need to make Russian cities and even Russian soldiers think about what they need: peace or Putin.”

Austin rejected the Ukrainian President’s request, noting that no single military weapon would be decisive in the ongoing fighting between Ukraine and Russia, emphasizing that the use of US and British weapons to attack targets inside Russia would only increase the chances for escalating the conflict, bringing a nuclear-armed Russia into direct combat against NATO forces.

On September 11, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, accompanied by British Foreign Secretary David Lammy, traveled to the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, where Zelensky once again pressured both men regarding permission to use ATACMS and Storm Shadow on targets inside Russia. Both men demurred, leaving the matter for a meeting scheduled between US President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Kier Starmer, on Friday, September 13.

The next day, September 12, Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to the press in Saint Petersburg, Russia, where he addressed the question of the potential use by Ukraine of US- and British-made weapons. “This will mean that NATO countries – the United States and European countries – are at war with Russia,” Putin said. “And if this is the case, then, bearing in mind the change in the essence of the conflict, we will make appropriate decisions in response to the threats that will be posed to us.”

President Biden took heed of the Russian President’s words, and despite being pressured by Prime Minister Starmer to greenlight the use of ATACMS and Storm Shadow by Ukraine, opted to continue the US policy of prohibiting such actions.

And there things stood, until November 18, when President Biden, responding to reports that North Korea had dispatched thousands of troops to Russia to join in the fighting against Ukrainian forces, reversed course, allowing US-provided intelligence to be converted into data used to guide both the ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles to their targets. These targets had been provided by Zelensky to the US back in September, when the Ukrainian President visited Biden at the White House. Zelensky had made striking these targets with ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles a key part of his so-called “victory plan.”

After the approval had been given by the US, Zelensky spoke to the press. “Today, there is a lot of talk in the media about us receiving a permit for respective actions,” he said. “Hits are not made with words. Such things don’t need announcements. Missiles will speak for themselves.”

The next day, November 19, Ukraine fired six ATACMS against targets near the Russian city of Bryansk. The day after—November 20—Ukraine fired Storm Shadow missiles against a Russian command post in the Kursk province of Russia.

The Ukrainian missiles had spoken.

The Russian response

Shortly after the Storm Shadow attacks on Kursk occurred, Ukrainian social media accounts began reporting that Ukrainian intelligence had determined that the Russians were preparing an RS-26 Rubezh missile for launch against Ukraine. These reports suggested that the intelligence came from US-provided warnings, including imagery, as well as intercepted radio communications from the Kapustin Yar missile test facility, located east of the Russian city of Astrakhan.

Test launch of an RS-26 missile

The RS-26 was a missile that, depending on its payload configuration, could either be classified as an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM, meaning it could reach ranges of over 5,500 kilometers) or an intermediate-range missile (IRBM, meaning it could fly between 1,000 and 3,000 kilometers). Given that the missile was developed and tested from 2012-2016, this meant the RS-26 would either be declared as an ICBM and be counted as part of the New Start Treaty, or as an IRBM, and as such be prohibited by the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The INF Treaty had been in force since July 1988 and had successfully mandated the elimination of an entire category of nuclear-armed weapons deemed to be among the most destabilizing in the world.

In 2017, the Russian government decided to halt the further development of the RS-26 given the complexities brought on by the competing arms control restrictions.

In 2019, then-President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the INF Treaty. The US immediately began testing intermediate-range cruise missiles and announced its intention to develop a new family of hypersonic intermediate range missiles known as Dark Eagle.

Despite this provocation, the Russian government announced a unilateral moratorium of producing and deploying IRBMs, declaring that this moratorium would remain in place until the US or NATO deployed an IRBM on European soil.

In September 2023, the US deployed a new containerized missile launch system capable of firing the Tomahawk cruise missile to Denmark as part of a NATO training exercise. The US withdrew the launcher from Denmark upon conclusion of the training.

In late June 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia would resume production of intermediate-range missiles, citing the US deployment of intermediate-range missiles to Denmark. “We need to start production of these strike systems and then, based on the actual situation, make decisions about where — if necessary to ensure our safety — to place them,” Putin said.

At that time the western media speculated about the mothballed RS-26 being brought back into production.

When Ukraine announced that it had detected an RS-26 being prepared for launch on November 20, many observers (including me) accepted this possibility, given the June announcement by President Putin and the associated speculation. As such, when on the night on November 21, the Ukrainians announced that an RS-26 missile had been launched from Kapustin Yar against a missile production facility in the city of Dnipropetrovsk, these reports were taken at face value.

As it turned out, we were all wrong.

Ukrainian intelligence, after examining missile debris from the attack, seems to support this assertion. Whereas the RS-26 was a derivative of the SS-27M ICBM, making use of its first and second stages, the Orezhnik, according to the Ukrainians, made use of the first and second stages of the new “Kedr” (Cedar) ICBM, which is in the early stages of development. Moreover, the weapons delivery system appears to be taken from the newly developed Yars-M, which uses independent post-boost vehicles, or IPBVs, known in Russian as blok individualnogo razvedeniya (BIR), instead of traditional multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles, or MIRVs.

In the classic weapons configuration for a modern Russian missile, the final stage of the missile, also known as the post-boost vehicle (PBV or bus), contains all the MIRVs. Once the missile exits the earth’s atmosphere, the PBV detaches from the missile body, and then independently maneuvers, releasing each warhead at the required point for it to reach its intended target. Since the MIRVs are all attached to the same PBV, the warheads are released over targets that are on a relatively linear path, limiting the area that can be targeted.

A missile using an IPBV configuration, however, can release each reentry vehicle at the same time, allowing each warhead to follow an independent trajectory to its target. This allows for greater flexibility and accuracy.

The Oreshnik was designed to carry between four and six IPBVs. The one used against Dnipropetrovsk was a six IPBV-capable system. Each war head in turn contained six separate submunitions, consisting of metal slugs forged from exotic alloys that enabled them to maintain their form during the extreme heat generated by hypersonic re-entry speeds. These slugs are not explosive; rather they use the combined effects of the kinetic impact at high speed and the extreme heat absorbed by the exotic alloy to destroy their intended target on impact.

The military industrial target struck by the Oreshnik was hit by six independent warheads, each containing six submunitions. In all, the Dnipropetrovsk facility was struck be 36 separate munitions, inflicting devastating damage, including to underground production facilities used by Ukraine and its NATO allies to produce short- and intermediate-range missiles.

These facilities were destroyed.

The Russians had spoken as well.

Back to the future

If history is the judge, the Oreshnik will likely mirror in terms of operational concept a Soviet-era missile, the Skorost, which was developed beginning in 1982 to counter the planned deployment by the United States of the Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missile to West Germany. The Skorost was, like the Oreshnik, an amalgam of technologies from missiles under development at the time, including an advanced version of the SS-20 IRBM, the yet-to-be deployed SS-25 ICBM, and the still under development SS-27. The result was a road-mobile two-stage missile which could carry either a conventional or nuclear payload that used a six-axle transporter-erector-launcher, or TEL (both the RS-26 and the Oreshnik likewise use a six-axle TEL).

In 1984, as the Skorost neared completion, the Soviet Strategic Missile Forces conducted exercises where SS-20 units practiced the tactics that would be used by the Skorost equipped forces. A total of three regiments of Skorost missiles were planned to be formed, comprising a total of 36 launchers and over 100 missiles. Bases for these units were constructed in 1985.

The Skorost missile and launcher

The Skorost was never deployed; production stopped in March 1987 as the Soviet Union prepared for the realities of the INF Treaty, which would have banned the Skorost system.

The history of the Skorost is important because the operational requirements for the system—to mirror the Pershing II missiles and quickly strike them in time of war—is the same mission given to the Oreshnik missile, with the Dark Eagle replacing the Pershing II.

But the Oreshnik can also strike other targets, including logistic facilities, command and control facilities, air defense facilities (indeed, the Russians just put the new Mk. 41 Aegis Ashore anti-ballistic missile defense facility that was activated on Polish soil on the Oreshnik’s target list).

In short, the Oreshnik is a game-changer in every way. In his November 21 remarks, Putin chided the United States, noting that the decision by President Trump in 2019 to withdraw from the INF Treaty was foolish, made even more so by the looming deployment of the Oreshnik missile, which would have been banned under the treaty.

On November 22, Putin announced that the Oreshnik was to enter serial production. He also noted that the Russians already had a significant stockpile of Oreshnik missiles that would enable Russia to respond to any new provocations by Ukraine and its western allies, thereby dismissing the assessments of western intelligence which held that, as an experimental system, the Russians did not have the ability to repeat attacks such as the one that took place on November 21.

As a conventionally armed weapon, the Oreshnik provides Russia with the means to strike strategic targets without resorting to the use of nuclear weapons. This means that if Russia were to decide to strike NATO targets because of any future Ukrainian provocation (or a direct provocation by NATO), it can do so without resorting to nuclear weapons.

Ready for a nuclear exchange

Complicating an already complicated situation is the fact that while the US and NATO try to wrestle with the re-emergence of a Russian intermediate-range missile threat that mirrors that of the SS-20, the appearance of which in the 1970’s threw the Americans and their European allies into a state of panic, Russia has, in response to the very actions which prompted the reemergence of INF weapons in Europe, issued a new nuclear doctrine which lowers the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons by Russia.

The original nuclear deterrence doctrine was published by Russia in 2020. In September 2024, responding to the debate taking place within the US and NATO about authorizing Ukraine to use US- and British-made missiles to attack targets on Russian soil, President Putin instructed his national security council to propose revisions to the 2020 doctrine based upon new realities.

The revamped document was signed into law by Putin on November 19, the same day that Ukraine fired six US-made ATACMS missiles against targets on Russian soil.

After announcing the adoption of the new nuclear doctrine, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitri Peskov was asked by reporters if a Ukrainian attack on Russia using ATACMS missiles could potentially trigger a nuclear response. Peskov noted that the doctrine’s provision allows the use of nuclear weapons in response to a conventional strike that raises critical threats for Russia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Peskov also noted that the doctrine’s new language holds that an attack by any country supported by a nuclear power would constitute a joint aggression against Russia that triggers the use of nuclear weapons by Russia in response.

Shortly after the new Russian doctrine was made public, Ukraine attacked the territory of Russia using ATACMS missiles.

The next day Ukraine attacked the territory of Russia using Storm Shadow missiles.

Under Russia’s new nuclear doctrine, these attacks could trigger a Russian nuclear response.

The new Russian nuclear doctrine emphasizes that nuclear weapons are “a means of deterrence,” and that their use by Russia would only be as an “extreme and compelled measure.” Russia, the doctrine states, “takes all necessary efforts to reduce the nuclear threat and prevent aggravation of interstate relations that could trigger military conflicts, including nuclear ones.”

Nuclear deterrence, the doctrine declares, is aimed at safeguarding the “sovereignty and territorial integrity of the state,” deterring a potential aggressor, or “in case of a military conflict, preventing an escalation of hostilities and stopping them on conditions acceptable for the Russian Federation.”

Russia has decided not to invoke its nuclear doctrine at this juncture, opting instead to inject the operational use of the new Oreshnik missile as an intermediate non-nuclear deterrence measure.

The issue at this juncture is whether the United States and its allies are cognizant of the danger their precipitous actions in authorizing Ukrainian attacks on Russian soil have caused.

The answer, unfortunately, appears to be “probably not.”

Rear Admiral Thomas Buchanan

Exhibit A in this regard are comments made by Rear Admiral Thomas Buchanan, the Director of Plans and Policy at the J5 (Strategy, Plans and Policy) for US Strategic Command, the unified combatant command responsible for deterring strategic attack (i.e., nuclear war) through a safe, secure, effective, and credible global combat capability and, when directed, to be ready to prevail in conflict. On November 20, Admiral Buchanan was the keynote speaker at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Project on Nuclear Issues conference in Washington, DC, where he drew upon his experience as the person responsible for turning presidential guidance into preparing and executing the nuclear war plans of the United States.

The host of the event drew upon Admiral Buchanan’s résumé when introducing him to the crowd, a tact which, on the surface, projected a sense of confidence in the nuclear warfighting establishment of the United States. The host also noted that it was fortuitous that Admiral Thomas would be speaking a day after Russia announced its new nuclear doctrine.

But when Admiral Buchanan began talking, such perceptions were quickly swept away by the reality that those responsible for the planning and implementation of America’s nuclear war doctrine were utterly clueless about what it is they are being called upon to do.

When speaking about America’s plans for nuclear war, Admiral Buchanan stated that “our plans are sufficient in terms of the actions they seek to hold the adversary to, and we are in a study of sufficiency,” noting that “the current program of record is sufficient today but may not be sufficient for the future.” He went on to articulate that this study “is underway now and will work well into the next administration, and we look forward to continuing that work and articulating how the future program could help provide the President additional options should he need them.”

In short, America’s nuclear war plans are nonsensical, which is apt, given the nonsensical reality of nuclear war.

Admiral Buchanan’s remarks are shaped by his world view which, in the case of Russia, is influenced by a NATO-centric interpretation of Russian actions and intent that is divorced from reality. “President Putin,” Admiral Buchanan declared, “has demonstrated a growing willingness to employ nuclear rhetoric to coerce the United States and our NATO allies to accept his attempt to change borders and rewrite history. This week, notwithstanding, was another one of those efforts.”

Putin, Buchanan continued, “has validated and updated his doctrine such that Russia has revised it to include the provision that nuclear retaliation against non-nuclear states would be considered if the state that supported it was supported by a nuclear state. This has serious implications for Ukraine and our NATO allies.”

Left unsaid was the fact that the current crisis over Ukraine is linked to a NATO strategy that sought to expand NATO’s boundaries up to the border of Russia despite assurances having been made that NATO would not expand “one inch eastward.” Likewise, Buchanan was mute on the stated objective of the administration of President Biden to use the conflict in Ukraine as a proxy war designed to inflict a “strategic defeat” on Russia.

Seen in this light, Russia’s nuclear doctrine goes from being a tool of intimidation, as articulated by Admiral Buchanan, to a tool of deterrence—mirroring the stated intent of America’s nuclear posture, but with much more clarity and purpose.

Admiral Buchanan did couch his comments by declaring from the start that, when it comes to nuclear war, “there is no winning here. Nobody wins. You know, the US is signed up to that language. Nuclear war cannot be won, must never be fought, et cetera.”

The first hydrogen bomb tested by the United States, 1952

When asked about the concept of “winning” a nuclear war, Buchanan replied that “it’s certainly complex, because we go down a lot of different avenues to talk about what is the condition of the United States in a post-nuclear exchange environment. And that is a place that’s a place we’d like to avoid, right? And so when we talk about non-nuclear and nuclear capabilities, we certainly don’t want to have an exchange, right?”

Right.

It would have been best if he had just stopped here. But Admiral Buchanan continued.

“I think everybody would agree if we have to have an exchange, then we want to do it in terms that are most acceptable to the United States. So it’s terms that are most acceptable to the United States that puts us in a position to continue to lead the world, right? So we’re largely viewed as the world leader. And do we lead the world in an area where we’ve considered loss? The answer is no, right? And so it would be to a point where we would maintain sufficient – we’d have to have sufficient capability. We’d have to have reserve capacity. You wouldn’t expend all of your resources to gain winning, right? Because then you have nothing to deter from at that point.”

Two things emerge from this statement. First is the notion that the United States believes it can fight and win a nuclear “exchange” with Russia.

Second is the idea that the United States can win a nuclear war with Russia while retaining enough strategic nuclear capacity to deter the rest of the world from engaging in a nuclear war after the nuclear war with Russia is done.

To “win” a nuclear war with Russia implies the United States has a war-winning plan.

Admiral Buchanan is the person in charge of preparing these plans. He has stated that these plans “are sufficient in terms of the actions they seek to hold the adversary to,” but this clearly is not the case—the United States has failed to deter Russia from issuing a new nuclear war doctrine and from employing in combat for the first time in history a strategic nuclear capable ballistic missile.

His plans have failed.

And he admits that “the current program of record is sufficient today but may not be sufficient for the future.”

Meaning we have no adequate plan for the future.

But we do have a plan.

One that is intended to produce a “victory” in a nuclear war Buchanan admits cannot be won and should never be fought.

One that will allow the United States to retain sufficient nuclear weapons in its arsenal to continue to “be a world leader” by sustaining its doctrine of nuclear deterrence.

A doctrine which, if the United States ever does engage in a “nuclear exchange” with Russia, would have failed.

There is only one scenario in which the United States could imagine a nuclear “exchange” with Russia which allows it to retain a meaningful nuclear weapons arsenal capable of continued deterrence.

And that scenario involves a pre-emptive nuclear strike against Russia’s strategic nuclear forces designed to eliminate most of Russia’s nuclear weapons.

Such an attack can only be carried out by the Trident missiles carried aboard the Ohio-class submarines of the United States Navy.

Hold that thought.

Russia is on record as saying that the use of ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles by Ukraine on targets inside Russia is enough to trigger the use of nuclear weapons in retaliation under its new nuclear doctrine.

At the time of this writing, the United States and Great Britain are in discussions with Ukraine about the possibility of authorizing new attacks on Russia using the ATACMS and Storm Shadow.

France just authorized Ukraine to use the French-made SCALP missile (a cousin to the Storm Shadow) against targets inside Russia.

And there are reports that the United States Navy has just announced that it is increasing the operational readiness status of its deployed Ohio-class submarines.

Trident D5 missile launch from an Ohio-class submarine

It is high time for everyone, from every walk of life, to understand the path we are currently on. Left unchecked, events are propelling us down a highway to hell that leads to only one destination—a nuclear Armageddon that everyone agrees can’t be won, and yet the United States is, at this very moment, preparing to “win.”

A nuclear “exchange” with Russia, even if the United States were able to execute a surprise preemptive nuclear strike, would result in the destruction of dozens of American cities and the deaths of more than a hundred million Americans.

And this is if we “win.”

And we know that we can’t “win” a nuclear war.

And yet we are actively preparing to fight one.

This insanity must stop.

Now.

The United States just held an election where the winning candidate, President-elect Donald Trump, campaigned on a platform which sought to end the war in Ukraine and avoid a nuclear war with Russia.

And yet the administration of President Joe Biden has embarked on a policy direction which seeks to expand the conflict in Ukraine and is bringing the United States to the very brink of a nuclear war with Russia.

This is a direct affront to the notion of American democracy.

By ignoring the stated will of the people of the United States as manifested through their votes in an election where the very issue of war and peace were front and center in the campaign, is an affront to democracy.

We the people of the United States must not allow this insane rush to war to continue.

We must put the Biden administration on notice that we are opposed to any expansion of the conflict in Ukraine which brings with it the possibility of escalation that leads to a nuclear war with Russia.

And we must implore the incoming Trump administration to speak out in opposition to this mad rush toward nuclear annihilation by restating publicly its position of the war in Ukraine and nuclear war with Russia—that the war must end now, and that there can be no nuclear war with Russia triggered by the war in Ukraine.

We need to say “no” to nuclear war.

I am working with other like-minded people to hold a rally in Washington, DC on the weekend of December 7-8 to say no to nuclear war.

I am encouraging Americans from all walks of life, all political persuasions, all social classes, to join and lend their voices to this cause.

Watch this space for more information about this rally.

All our lives depend on it.

0 Comments