The Democrats Have Lost the Plot

by Matt Taibbi | Mar 10, 2023

Testifying with Michael Shellenberger before a House Subcommittee was one of the more surreal experiences of my life. I expected serious attacks and spent a nervous night before preparing for them. Then the hearing began, and an episode of Black Adder: Congress broke out. The attacks happened, but it was more farcical horror and a parade of self-owns that made me more sad than upset.

The Democrats made it clear they were not interested in talking about free speech except as it pertains to Chrissy Teigen, seemed to suggest a journalist should not make a living, and finally made the incredible claim that Michael and I represented a “direct threat to people who oppose them.” Of all that transpired yesterday, this was the most ominous development — perhaps not for me but for reporters generally, given our government’s recent history of dealing with people deemed “threats.”

Beyond that, much of the hubbub yesterday involved the many “When did Elon Musk start beating your wife?” questions, and the line about me being a “so-called journalist.”

Regarding the former, both ranking member Stacey Plaskett and Texas Democrat Sylvia Garcia repeatedly asked questions about when I first got Twitter Files information, and from whom. It was a bizarre collective display of a whole group of politicians not understanding some pretty basic things about how not to act around journalists.

Obviously, mine is not a situation where there’s a mole at Langley or in a war zone smuggling out documents, whose life is at stake. The genesis of the Twitter Files story also is not exactly a case for Sherlock Holmes.

But, I made an agreement on an attribution, and the reason I can’t break it is as much for the next source as it is for any current one (or ones, in this case). People who are thinking of calling a journalist always look them up to see if they’ve ever burned or blown a source before. So, if you happen to have done it on television, that’s going to be a serious problem going forward.

Moreover, submitting to an elected official’s request to break any deal is not exactly doing future journalists a favor, because it sets a precedent. This is why anyone who understands and respects these dynamics doesn’t go near that question. Yet the Democrats did it repeatedly.

One of the crazier parts came at the end of the examination by Garcia, when I ended up becoming just a bystander to a heated and apparently sincerely unfriendly blowup between chairman Jim Jordan and Plaskett:

GARCIA: So you’re not gonna tell us when Musk first approached you

TAIBBI: Again, Congresswoman, you’re asking me to, you’re asking your journalist to reveal a source.

GARCIA: So then you consider Mr. Musk to be the direct source of all this?

TAIBBI: Now you’re, you’re trying to get me to say that he is the source.

GARCIA: Well, he isn’t, if you’re telling me you can’t answer because it’s your source, the only logical conclusion is that he is in fact your source.

TAIBBI: Well, you’re free to conclude that.

GARCIA: Well, sir, I just don’t understand. You can’t have it both ways, but let’s move on, because —

JORDAN: Well, no, he can. He’s a journalist.

PLASKETT: He can, because either Musk is the source and he can’t talk about it, or Musk is not the source. And if Musk is not the source, then he can discuss.

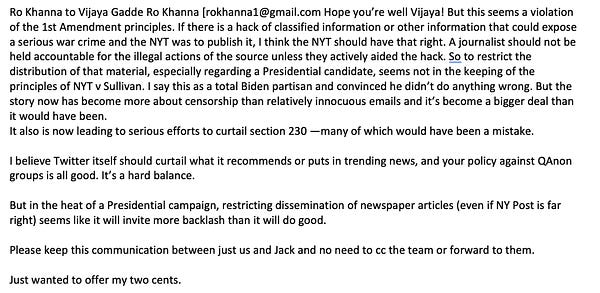

Did these people really not understand that identifying who is not a source crosses the same line as identifying who is one? You just can’t go into these questions. I started to interject to point this out, then realized that Garcia and Plaskett legitimately didn’t even know the basics of the civil liberties landscape. This was much the same as when Vijaya Gadde acted completely at a loss when Ro Khanna wrote to her in the middle of the Hunter Biden laptop affair, to express concerns about speech rights:

Khanna mentioned the New York Times v. Sullivan case and other principles to Gadde, and she seemed to have no idea what he was talking about. This was like that. Garcia also made it clear she didn’t know what Twitter was. At one point she said, regarding yesterday’s Twitter Files thread, that I had said “I had to attribute all the sources to Twitter first.”

I was so confused by this that I paused, worried that I was misunderstanding (my hearing is not so great). She then asked if I “sent it to Twitter first.” As I was replying no, that I’d posted the thread on Twitter, I heard an aide whispering something about “putting it on Twitter.”

Garcia seemed to think that Twitter was an editorial body to which I was sending text, maybe for review. It’s understandable, not knowing that the platform doesn’t work that way — not everyone has to be on Twitter obviously — but then why the hostility? Instead of simply asking me in a friendly way about this process, which I would have been glad to explain, she kept blasting away. “First, sir. Yes or no?”

The Democrats were angry that Michael and I were there at all. They did not want to have a discussion about anything. It was completely opposite to what the party was even ten years ago, when expression rights were an issue they wanted to own.

Most of the ideas I have about issues like speech, civil liberties, and due process are from Democrats. I come from a family of Democrats and my mother is both a Democrat and a lawyer. So I was shocked when Dan Goldman of New York started quizzing Mike and me about “the two indictments by Special Counsel Robert Mueller that definitively established that Russia interfered in our 2016 election through social media disinformation, and a hack and leak operation.”

A longtime editor once cracked that the Democrats have been stuck since the mid-sixties trying to run Kennedy clones in elections, cranking out one toothy, tallish facsimile after another, from Gary Hart to John Kerry to Beto O’Rourke. Goldman is one of the latest, a literal handsome Dan who’s an heir to the Levi Strauss fortune, worth over $250 million, and who opposed Medicare for All and the Green New Deal while marketing himself as “tough on crime.” All of these qualities make him the kind of quintessential born-on-third-base triangulator the party loves.

However, the most salient fact about Goldman is that he has a J.D. from Stanford Law and is a former Assistant U.S. Attorney from the Southern District. Even the former lead counsel of a Trump impeachment, which Goldman is, should know better than to assert that an indictment can “definitively establish” anything.

This is why we have trials. A prosecutor’s assertions aren’t fact. They can only be said to be proven if they hold up against evidence presented by a competent defense in a fair trial setting. This is civil liberties 101, which is why I was confused when Goldman turned to me and asked if I “agreed” with Mueller’s indictments:

GOLDMAN: Mr. Taibbi, do you disagree with those two indictments?

If you watch the video, you’ll see me freeze again. I was trying to figure out: was Goldman asking if I agreed that the accused in those two Mueller cases were guilty? Or was he asking if I agreed with Mueller’s decision to indict?

I didn’t have enough information to answer either question, but I was about to ask Goldman to specify anyway. However, by that point I’d been chastised so many times by Democratic members for saying something other than “yes” or “no” that I knew even a respectful request for clarification would be cut off. So, I stammered out a demurral.

TAIBBI: Well, ind— uh, indictments aren’t a thing to disagree with.

GOLDMAN: Do you disagree? There are about 40 or 50 pages. Do you disagree with the evidence outlined in those indictments?

TAIBBI: Indictments are just charges.

As it happens I’d read those indictments, carefully, referencing them many times in Russiagate stories. Both are very unusual cases. USA v. Netyksho, Antonov, Badin, et al is Mueller’s much-ballyhooed case against 12 suspected officers of the GRU. The evidence in the indictment was frequently described as “highly detailed” and “compelling,” with NPR going so far as to say it demonstrated the “godlike vision” of the “U.S. intelligence community.” The indictment is indeed detailed, telling us hackers searched DCCC and DNC computers for terms like “hillary,” “cruz,” and “trump” and that unit 74455 of the GRU controlled or manipulated the personas “Guccifer 2.0” and “DCLeaks.”

Which is all fine and interesting, but the indictment offered no clue on how the state planned to prove the connection of the various activities, or moreover how they planned to prove that they used Guccifer to dump hacked materials to “Organization 1,” their word for Wikileaks, which they described as having “previously posted documents stolen from U.S. persons, entities, and the U.S. government.” Also, it was abundantly clear from the start that if these 12 people were GRU officers, none were going to show up in court. It’s even harder to evaluate “evidence” in an indictment if you know the prosecutor knows he or she is never going to have to prove the case.

In a normal criminal case you can often see where the evidence is going to come from, which witnesses might testify, what exhibits might be introduced, and so on. It’s at least theoretically possible to judge whether or not the state has a decent case. In neither of these Mueller cases was that true, which incidentally was also the problem with evaluating them as news stories. If you don’t know where they got the information, how they’re determining who controls DCLeaks and Guccifer, and especially how they planned to link all of this to Wikileaks, how do you evaluate the truth of the story? A Clinton-appointed judge in 2019 tossed out many of the same assertions for the same reasons in the Democratic Party’s failed civil suit against Russia, Wikileaks, and the Trump campaign.

All of which brings us to USA v. Internet Research Agency, Concord Catering, Prigozhin. This is the one where Mueller laid out the IRA’s plan to “sow discord” in the U.S. using social media. This is the case the Justice Department had to drop because one of the defendants, Concord, did show up in court, when the DOJ decided going through with the discovery process “unreasonably risk[ed] the national security interests of the United States.”

This made the end of Goldman’s foray in this direction all the more confusing:

GOLDMAN: Because you said earlier, I believe that you did not see Russia— you could not confirm that Russia interfered in our election in 2016, that you don’t believe that. Is that your testimony here today? You don’t believe that they did?

TAIBBI: I think it’s possible that they may have on a small scale, but certainly not to what’s been reported.

GOLDMAN: What’s been reported or what’s been included in the indictments?

TAIBBI: Well, again, indictments are allegations. They’re not proof.

GOLDMAN: I understand. It’s pretty detailed allegations…

TAIBBI: And the Mueller indictment, by the way —

GOLDMAN: You should go back and read the indictments, and tell us if you think there’s no proof of it.

Here I was going to point out that the second of the cases Goldman cited had been dropped by prosecutors because Concord showed up in court, but Goldman stepped on that quickly:

TAIBBI: Some of those defendants, by the way…

GOLDMAN: Let me move on. Please, let me move on. That’s how this works. You should know this by now.

The irony is that what Goldman was doing, confusing accusations with proof — as Thomas Jefferson said, the phenomenon of people whose “suspicions may be evidence” — was the entire reason for the hearing. Michael and I were trying to describe a system that wants to bypass proof and proceed to punishment, a radical idea that this new breed of Democrat embraces. I think they justify this using the Sam Harris argument, that in pursuit of suppressing Trump, anything is justified. But by removing or disrespecting the rights to which Americans are accustomed, you make opposition movements like Trump’s, you don’t stop them.

Yesterday was memorable for other reasons, but a depressing eye-opener as well, forcing me to see up close the intellectual desert that’s spread all the way to the edges within the party I once supported. There are no more pockets of Wellstones and Kuciniches who were once tolerated and whose job it is to uphold a constitutionalist position within the larger whole. That crucial little pocket of principle is gone, and I don’t think it’s coming back.

0 Comments